полная версия

полная версияThe Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 13, No. 357, February 21, 1829

PERSIAN CAVALIER

The following sketch of a Persian cavalier has the richness and freshness of one of Heber's, or Morier's or Sir John Malcolm's pages:—"He was a man of goodly stature, and powerful frame; his countenance, hard, strongly marked, and furnished with a thick, black beard, bore testimony of exposure to many a blast, but it still preserved a prepossessing expression of good humour and benevolence. His turban, which was formed of a cashmere shawl, sorely tached and torn, and twisted here and there with small steel chains, according to the fashion of the time, was wound around a red cloth cap, that rose in four peaks high above the head. His oemah, or riding coat, of crimson cloth much stained and faded, opening at the bosom, showed the links of a coat of mail which he wore below; a yellow shawl formed his girdle; his huge shulwars, or riding trousers, of thick, fawn-coloured Kerman woollen-stuff, fell in folds over the large red leather boots in which his legs were cased: by his side hung a crooked scymetar in a black leather scabbard, and from the holsters of his saddle peeped out the butt ends of a pair of pistols; weapons of which I then knew not the use, any more than of the matchlock which was slung at his back. He was mounted on a powerful but jaded horse, and appeared to have already travelled far."—Kuzzilbash.

ORATORY

The national glory of Great Britain rests, in no small degree, on the refined taste and classical education of her politicians; and the portion of her oratory acknowledged to be the most energetic, bears the greatest resemblance to the spirit of Demosthenes.—North American Review.

GRESHAM COLLEGE. 8

The City of London could not do a more fitting thing than to convert the Gresham lectureships into fourteen scholarships for King's College, retaining the name and reserving the right of presentation. A bounty which is at present useless would thus be rendered efficient, and to the very end which was intended by Gresham himself. An act of parliament would be necessary; and the annexations would of course take place as the lectureships became vacant.—Quarterly Rev.

In Germany, seminaries for the education of popular teachers, are conducted by distinguished divines of each state, who, for the most part, reside in the capital, and are the same persons who examine each clergyman three times before his ordination. Unless a candidate can give evidence of his ability, and of, at least, a two years' stay in those popular Institutions where religious instruction is the main object, he is not allowed to teach any branch of knowledge whatever. —Russell's Tour in Germany.

MUNGO PARK

Captain Clapperton being near that part of the Quorra, where Mungo Park perished, our traveller thought he might get some information of this melancholy event. The head man's story is this:– "That the boat stuck fast between two rocks; that the people in it laid out four anchors a-head; that the water falls down with great rapidity from the rocks, and that the white men, in attempting to get on shore, were drowned; that crowds of people went to look at them, but the white men did not shoot at them as I had heard; that the natives were too much frightened either to shoot at them or to assist them; that there were found a great many things in the boat, books and riches, which the Sultan of Boussa has got; that beef cut in slices and salted was in great plenty in the boat; that the people of Boussa who had eaten of it all died, because it was human flesh, and that they knew we white men eat human flesh. I was indebted to the messenger of Yarro for a defence, who told the narrator that I was much more nice in my eating than his countrymen were. But it was with some difficulty I could persuade him that if his story was true, it was the people's own fears that had killed them; that the meat was good beef or mutton: that I had eaten more goats' flesh since I had been in this country than ever I had done in my life; that in England we eat nothing but fowls, beef, and mutton."—Clapperton's Travels.

SILK

We find in a statement of the raw silk imported into England, from all parts of the world, that in 1814, it amounted to one million, six hundred and thirty-four thousand, five hundred and one pounds; and in 1824, to three millions, three hundred and eighty-two thousand, three hundred and fifty-seven.9 Italy, which is not better situated in regard to the culture of silk than a large portion of the United States, furnishes to the English fabrics about eight hundred thousand pounds' weight. The Bengal silk is complained of by the British manufacturers, on account of its defective preparation; by bestowing more care on his produce, the American cultivator could have in England the advantage over the British East Indies. It is a fact well worthy of notice, and the accuracy of which seems warranted by its having been brought before a Committee of both Houses of Parliament, that the labour in preparing new silk affords much more employment to the country producing it, than any other raw material. It appears from an official document, that the value of the imports of raw silk into France, during the year 1824, amounted to thirty seven millions, one hundred and forty-nine thousand, nine hundred and sixty francs.—North American Review.

CHINESE NOVELS

A union of three persons, cemented by a conformity of taste and character, constitutes, in the opinion of the Chinese, the perfection of earthly happiness, a sort of ideal bliss, reserved by heaven for peculiar favourites as a suitable reward for their talent and virtue. Looking at the subject under this point of view, their novel-writers not unfrequently arrange matters so as to secure this double felicity to their heroes at the close of the work; and a catastrophe of this kind is regarded as the most satisfactory that can be employed. Without exposing ourselves to the danger incurred by one of the German divines, who was nearly torn to pieces by the mob of Stockholm for defending polygamy, we may venture to remark, that for the mere purposes of art, this system certainly possesses very great advantages. It furnishes the novel-writer with an easy method of giving general satisfaction to all his characters, at the end of the tale, without recurring to the fatal though convenient intervention of consumption and suicide, with us the only resources, when there happens to be a heroine too many. What floods of tears would not the Chinese method have spared to the high-minded Corinna, to the interesting and poetical Clementina! From what bitter pangs would it not have relieved the irresolute Oswald, perhaps even the virtuous Grandison himself! The Chinese are entitled to the honour of having invented the domestic and historical novel several centuries before they were introduced in Europe. Fables, tales of supernatural events, and epic poems, belong to the infancy of nations; but the real novel is the product of a later period in the progress of society, when men are led to reflect upon the incidents of domestic life, the movement of the passions, the analysis of sentiment, and the conflicts of adverse interests and opinions. —Preface to a French Translation of a Chinese Novel.

HERO OF A CHINESE NOVEL

There came out a youth of about fifteen or sixteen years of age, dressed in a violet robe with a light cap on his head. His vermilion lips, brilliant white teeth, and arched eye-brows gave him the air of a charming girl. So graceful and airy are his movements, that one might well ask, whether he be mortal or a heavenly spirit. He looks like a sylph formed of the essence of flowers, or a soul descended from the moon. Is it indeed a youth who has come out to divert himself, or is it a sweet perfume from the inner apartment?—Ibid.

BEES

It has been the custom, from the earliest ages, to rub the inside of the hive with a handful of salt and clover, or some other grass or sweet-scented herb, previously to the swarm's being put in the hive. We have seen no advantage in this; on the contrary, it gives a great deal of unnecessary labour to the bees, as they will be compelled to remove every particle of foreign matter from the hive before they begin to work. A clean, cool hive, free from any peculiar smell or mustiness, will be acceptable to the bees; and the more closely the hive is joined together, the less labour will the insects have, whose first care it is to stop up every crevice, that light and air may be excluded. We must not omit to reprehend, as utterly useless, the vile practice of making an astounding noise, with tin pans and kettles, when the bees are swarming. It may have originated in some ancient superstition, or it may have been the signal to call aid from the fields, to assist in the hiving. If harmless it is unnecessary; and everything that tends to encumber the management of bees should be avoided.—American Farmer's Manual.

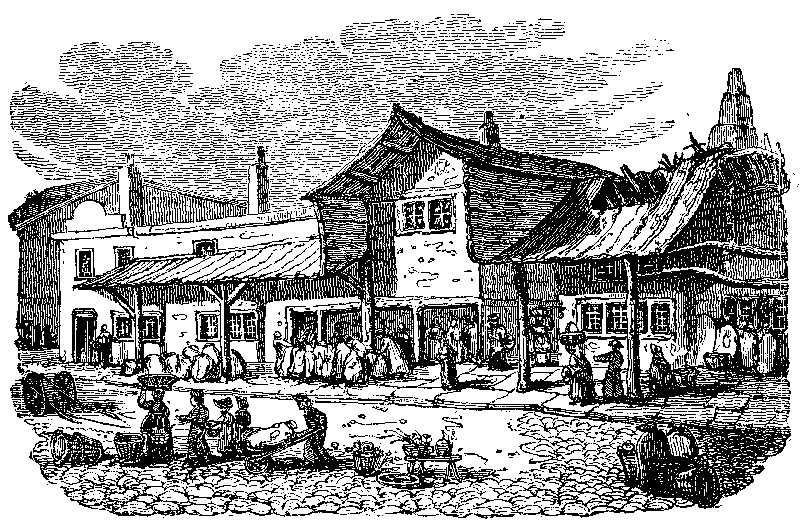

CONVENT GARDEN MARKET

Covent Garden Market.—"Here to-day, and gone to-morrow."—Tristram Shandy.

I know some of the ugliest men who are the most agreeable fellows in the world. The ladies may doubt this remark; but if they compel me to produce an example, I shall waive all modesty, and prove my veracity by quoting myself. I have often thought how it is that ugliness contrives to invest itself with a "certain something," that not only destroys its disagreeable properties, but actually commands an interest—(by the by, this is referring generally, and nothing personal to myself.) I philosophically refer it all to the balance of nature. Now I know some very ugly places that have a degree of interest, and here again I fancy a lady's sceptical ejaculation, "Indeed!" Ay, but it is so; and let us go no further than Covent Garden. Enter it from Russell-street. What can be more unsightly,—with its piles of cabbages in the street, and basket-measures on the roofs of the shops—narrow alleys, wooden buildings, rotting vegetables "undique," and swarms of Irish basket-women, who wander about like the ghosts on this side of the Styx, and who, in habits, features, and dialect, appear as if belonging to another world. Yet the Garden, like every garden, has its charms. I have lounged through it on a summer's day, mixing with pretty women, looking upon choice fruit, smelling delicious roses, with now and then an admixture of sundry disagreeables, such as a vigorous puff out of an ugly old woman's doodeen, just as you are about to make a pretty speech to a much prettier lady—to say nothing of the unpleasant odours arising from heaps of putrescent vegetables, or your hat being suddenly knocked off by a contact with some unlucky Irish basket-woman, with cabbages piled on her head sufficient for a month's consumption at Williams's boiled beef and cabbage warehouse, in the Old Bailey. The narrow passages through this mart remind me of the Chinese streets, where all is shop, bustle, squeeze, and commerce. The lips of the fair promenaders I collate (in my mind's eye, gentle reader) with the delicious cherry, and match their complexions with the peach, the nectarine, the rose, red or white, and even sometimes with the russet apple. Then again I lounge amidst chests of oranges, baskets of nuts, and other et cetera, which, as boys, we relished in the play-ground, or, in maturer years, have enjoyed at the wine feast. Here I can saunter in a green-house among plants and heaths, studying botany and beauty. Facing me is a herb-shop, where old nurses, like Medeas of the day, obtain herbs for the sick and dying; and within a door or two flourishes a vender of the choicest fruits, with a rich display of every luxury to delight the living and the healthy.

I know of no spot where such variety may be seen in so small a compass. Rich and poor, from the almost naked to the almost naked lady (of fashion, of course.) "Oh crikey, Bill," roared a chimney-sweep in high glee. The villain turned a pirouette in his rags, and in the centre mall of the Garden too; he finished it awkwardly, made a stagger, and recovered himself against—what?—"Animus meminisse horret"—against a lady's white gown! But he apologized. Oh, ye gods! his apology was so sincere, his manner was so sincere, that the true and thorough gentleman was in his every act and word. (Mem. merely as a corroboration, the lady forgave him.) What a lesson would this act of the man of high callings (from the chimney-tops) have been to our mustachioed and be-whiskered dandies, who, instead of apologizing to a female after they may have splashed her from head to foot, trod on her heel, or nearly carried away her bonnet, feathers, cap, and wig, only add to her confusion by an unmanly, impudent stare or sneer!

But to the Garden again. I like it much; it is replete with humour, fun, and drollery; it contributes a handsome revenue to the pocket of his Grace the Duke of Bedford, besides supplying half the town with cabbages and melons, (the richest Melon on record came from Covent-Garden, and was graciously presented to our gracious sovereign.)

The south side appears to be devoted to potatoes, a useful esculent, and of greater use to the poor than all the melons in christendom. Here kidneys and champions are to be seen from Scotland, York, and Kent; and here have I observed the haggard forms of withered women

"In rags and tatters, friendless and forlorn,"creeping from shop to shop, bargaining for "a good pen'orth of the best boilers;" and here have I often watched the sturdy Irishman walking with a regular connoisseur's eye, peeping out above a short pipe, and below a narrow-brimmed hat,—a perfect, keen, twinkling, connoisseur's eye, critically examining every basket for the best lot of his own peculiar.

Now let us take a retrospective view of this our noble theme, and our interest will be the more strengthened thereon. All the world knows that a convent stood in this neighbourhood, and the present market was the garden, undè Convent Garden; would that all etymologists were as distinct. Of course the monastic institution was abolished in the time of Henry VIII., when he plundered convents and monasteries with as much gusto as boys abolish wasps-nests. After this it was given to Edmund Seymour, Duke of Somerset, brother-in-law to Henry VIII., afterwards the protector of his country, but not of himself for he was beheaded in 1552. The estate then became, by royal grant, the property of the Bedford family; and in the Privy Council Records for March, 1552, is the following entry of the transfer:—"A patent granted to John, Earl of Bedford, of the gifts of the Convent Garden, lying in the parish of St. Martin's-in-the-Fields, near Charing Cross, with seven acres, called Long Acre, of the yearly value of 6l. 6s. 8d. parcel of the possessions of the late Duke of Somerset, to have to him and his heirs, reserving a tenure to the king's majesty in socage, and not in capite." In 1634, Francis, Earl of Bedford, began to clear away the old buildings, and form the present square; and in 1671, a patent was granted for a market, which shows the rapid state of improvement in this neighbourhood, because in the Harleian MSS., No. 5,900, British Museum, is a letter, written in the early part of Charles II., by an observing foreigner to his friend abroad, who notices Bloomsbury, Hungerford, Newport, and other markets, but never hints of the likelihood or prospect of one being established in Covent Garden; yet before Charles's death the patent was obtained. It is a market, sui generis, confined mostly to vegetables and fruits; and the plan reflects much credit upon the speculative powers of the noble earl who founded it.

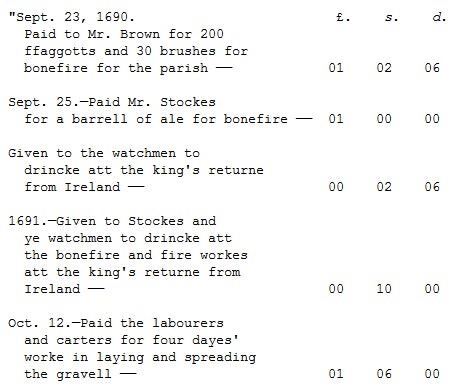

Thus far goes the public history; now let us turn to the private memoranda. In 1690, the parish, being very loyal, gave a grand display of fire-works on the happy return of William the Third from Ireland; and in the parish books appear the following entries on the subject, which will give some idea of the moderate charges of parish festivities in those "dark ages."

Making a grand total of £4. 1s. 0d. for a St. Paul's parish fête; but this was in 1690. This festival was of sufficient note to engage the artist's attention, and an engraving of it was sold by "B. Lens, between Bridewell and Fleet Bridge in Blackfryers."

Convent Garden has been the abode of talented and noble men. Richardson's Hotel was the residence of Dr. Hunter, the anatomical lecturer; and in 1724, Sir James Thornhill, who painted the dome of St. Paul's Cathedral, resided in this garden and opened a school for drawing in his house. Moreover, for the honour of the Garden, be it known, that at Sir Francis Kynaston's house therein situated, Charles the First established an academy called "Museum Minervæ," for the instruction of gentlemen in arts and sciences, knowledge of medals, antiquities, painting, architecture, and foreign languages. Not a vestige remains of the museum establishment now-a-days, or the subjects it embraced, unless it be foreign languages, including wild Irish, and very low English. Even as late as 1722, Lord Ferrers lived in Convent Garden; but this is trifling compared with the list of nobles who have lived around about this attractive spot, where nuns wandered in cloistered innocence, and now, oh! for sentimentality, what a relief to a fine, sensitive mind, or a sickly milliner!

In the front of the church quacks used to harangue the mob and give advice gratis. Westminster elections are held also on the same spot—that's a coincidence.

A CORRESPONDENT.

Manners & Customs of all Nations

AFRICAN FESTIVITIES

At Yourriba Captain Clapperton was invited to theatrical entertainments, quite as amusing, and almost as refined as any which his celestial Majesty can command to be exhibited before a foreign ambassador. The king of Yourriba made a point of our traveller staying to witness these entertainments. They were exhibited in the king's park, in a square space, surrounded by clumps of trees. The first performance was that of a number of men dancing and tumbling about in sacks, having their heads fantastically decorated with strips of rags, damask silk, and cotton of variegated colours; and they performed to admiration. The second exhibition was hunting the boa snake, by the men in the sacks. The huge snake, it seems, went through the motions of this kind of reptile, "in a very natural manner, though it appeared to be rather full in the belly, opening and shutting its mouth in the most natural manner imaginable." A running fight ensued, which lasted some time, till at length the chief of the bag-men contrived to scotch his tail with a tremendous sword, when he gasped, twisted up, seemed in great torture, endeavouring to bite his assailants, who hoisted him on their shoulders, and bore him off in triumph. The festivities of the day concluded with the exhibition of the white devil, which had the appearance of a human figure in white wax, looking miserably thin and as if starved with cold, taking snuff, rubbing his hands, treading the ground as if tender-footed, and evidently meant to burlesque and ridicule a white man, while his sable majesty frequently appealed to Clapperton whether it was not well performed. After this the king's women sang in chorus, and were accompanied by the whole crowd.

The price of a slave at Jannah, as nearly as can be calculated, is from 3l. to 4l. sterling; their domestic slaves, however, are never sold, except for misconduct.

AFRICAN WIDOW

Capt. Clapperton tells of a widow's arrival in town, with a drummer beating before her, whose cap was bedecked with ostrich feathers; a bowman walking on foot at the head of her horse; a train behind, armed with bows, swords, and spears. She rode a-straddle on a fine horse, whose trappings were of the first order for this country. The head of the horse was ornamented with brass plates, the neck with brass bells, and charms sewed in various coloured leather, such as red, green, and yellow; a scarlet breast-piece, with a brass plate in the centre; scarlet saddle-cloth, trimmed with lace. She was dressed in red silk trousers, and red morocco boots; on her head a white turban, and over her shoulders a mantle of silk and gold. Had she been somewhat younger and less corpulent, there might have been great temptation to head her party, for she had certainly been a very handsome woman, and such as would have been thought a beauty in any country in Europe.

AFRICAN NURSE

She was of a dark copper colour. In dress and countenance, very like one of Captain Lyon's female Esquimaux. She was mounted on a long-backed bright bay horse, with a scraggy tale, crop-eared, and the mane as if the rats had eaten part of it; and he was not in high condition. She rode a-straddle; had on a conical straw dish-cover for a hat, or to shade her face from the sun, a short, dirty, white bedgown, a pair of dirty, white, loose and wide trousers, a pair of Houssa boots, which are wide, and came up over the knee, fastened with a string round the waist. She had also a whip and spurs. At her saddle-bow hung about half a dozen gourds, filled with water, and a brass basin to drink out of; and with this she supplied the wounded and the thirsty. I certainly was much obliged to her, for she twice gave me a basin of water. The heat and the dust made thirst almost intolerable —Clapperton's Travels.

SPIRIT OF THE PUBLIC JOURNALS

THE BOXES

(To the Editor of Blackwood's Magazine.)Sir,—In the course of my study in the English language, which I made now for three years, I always read your periodically, and now think myself capable to write at your Magazin. I love always the modesty, or you shall have a letter of me very long time past. But, never mind, I would well tell you, that I am come to this country to instruct me in the manners, the customs, the habits, the policies, and the other affairs general of Great Britain. And truly I think me good fortunate, being received in many families, so as I can to speak your language now with so much facility as the French.

But, never mind. That what I would you say, is not only for the Englishes, but for the strangers, who come at your country from all the other kingdoms, polite and instructed; because, as they tell me, that they are abonnements10 for you in all the kingdoms in Europe, so well as in the Orientals and Occidentals.

No, sir, upon my honour, I am not egotist. I not proud myself with chateaux en Espagne. I am but a particular gentleman, come here for that what I said; but, since I learn to comprehend the language, I discover that I am become an object of pleasantry, and for himself to mock, to one of your comedians even before I put my foot upon the ground at Douvres. He was Mr. Mathew, who tell of some contretems of me and your word detestable Box. Well, never mind. I know at present how it happen, because I see him since in some parties and dinners; and he confess he love much to go travel and mix himself altogether up with the stage-coach and vapouring11 boat for fun, what he bring at his theatre.

Well, never mind. He see me, perhaps, to ask a question in the paque-bot—but he not confess after, that he goed and bribe the garçon at the hotel and the coach man to mystify me with all the boxes; but, very well, I shall tell you how it arrived, so as you shall see that it was impossible that a stranger could miss to be perplexed, and to advertise the travellers what will come after, that they shall converse with the gentlemen and not with the badinstructs.

But, it must that I begin. I am a gentleman, and my goods are in the public rentes,12 and a chateau with a handsome propriety on the bank of the Loire, which I lend to a merchant English, who pay me very well in London for my expenses. Very well. I like the peace, nevertheless that I was force, at other time, to go to war with Napoleon. But it is passed. So I come to Paris in my proper post-chaise, where I selled him, and hire one, for almost nothing at all, for bring me to Calais all alone, because I will not bring my valet to speak French here where all the world is ignorant.