полная версия

полная версияThe Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 13, No. 357, February 21, 1829

Various

The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction / Volume 13, No. 357, February 21, 1829

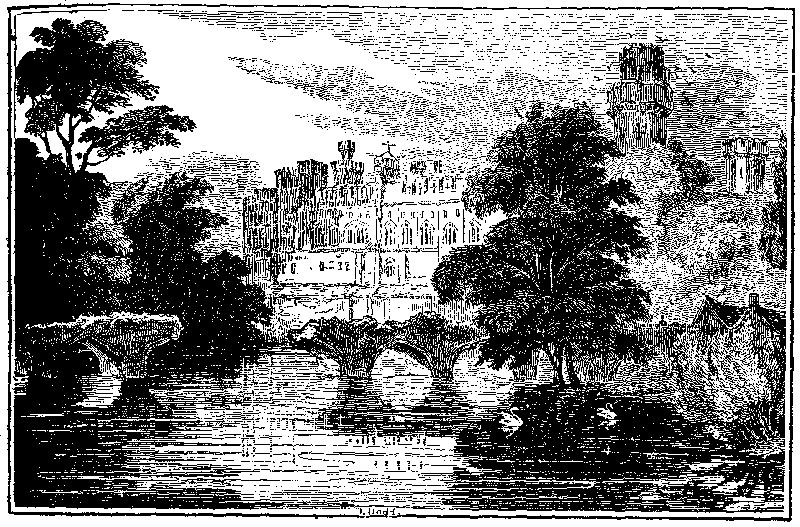

WARWICK CASTLE.

WARWICK CASTLE

The history of a fabric, so intimately connected with some of the most important events recorded in the chronicles of our country, as that of Warwick Castle, cannot fail to be alike interesting to the antiquary, the historian, and the man of letters. This noble edifice is also rendered the more attractive, as being one of the very few that have escaped the ravages of war, or have defied the mouldering hand of time; it having been inhabited from its first foundation up to the present time, a period of nearly one thousand years. Before, however, noticing the castle, it will be necessary to make a few remarks on the antiquity of the town of which it is the chief ornament.

The town of Warwick is delightfully situated on the banks of the river Avon, nearly in the centre of the county to which it has given its name, and of which it is the principal town. Much diversity of opinion exists among antiquaries, as to whether it be of Roman or Saxon origin; but it is the opinion of Rous, as well as that of the learned Dugdale,1 that its foundation is as remote as the earliest period of the Christian era. These authors attribute its erection to Gutheline, or Kimbeline, a British king, who called it after his own name, Caer-Guthleon, a compound of the British word Caer, (civitas,) and Gutieon, or Gutheline, which afterwards, for the sake of brevity, was usually denominated Caerleon. We are also informed that Guiderius, the son and successor of Kimbeline, greatly extended it, granting thereto numerous privileges and immunities; but being afterwards almost totally destroyed by the incursions of the Picts and Scots, it lay in a ruinous condition until it was rebuilt by the renowned Caractacus. This town afterwards greatly suffered from the ravages of the Danish invaders; but was again repaired by the lady Ethelfleda, the daughter of King Alfred, to whom it had been given, together with the kingdom of Mercia, of which it was the capital, by her father. Camden,2 with whose opinion several other antiquaries also concur, supposes that Warwick was the ancient Præsidium of the Romans, and the post where the præfect of the Dalmatian horse was stationed by the governor of Britain, as mentioned in the Notitia.

The appearance of this town in the time of Leland is thus described by that celebrated writer:—"The town of Warwick hath been right strongly defended and waullid, having a compace of a good mile within the waul. The dike is most manifestly perceived from the castelle to the west gate, and there is a great crest of yearth that the waul stood on. Within the precincts of the toune is but one paroche chirche, dedicated to St. Mary, standing in the middle of the toune, faire and large. The toune standeth on a main rokki hill, rising from est to west. The beauty and glory of it is yn two streetes, whereof the hye street goes from est to west, having a righte goodely crosse in the middle of it, making a quadrivium, and goeth from north to south." Its present name is derived, according to Matthew Paris, from Warmund, the father of Offa, king of the Mercians, who rebuilt it, and called it after his own name, Warwick.3

The castle, which is one of the most magnificent specimens of the ancient baronial splendour of our ancestors now remaining in this kingdom, rears its proud and lofty turrets, gray with age, in the immediate vicinity of the town. It stands on a rocky eminence, forty feet in perpendicular height, and overhanging the river, which laves its base. The first fortified building on this spot was erected by the before-mentioned lady Ethelfleda, who built the donjon upon an artificial mound of earth. No part of that edifice, however, is now supposed to remain, except the mound, which is still to be traced in the western part of the grounds surrounding the castle. The present structure is evidently the work of different ages, the most ancient part being erected, as appears from the "Domesday Book," in the reign of Edward the Confessor; which document also informs us, that it was "a special strong hold for the midland part of the kingdom." In the reign of William the Norman it received considerable additions and improvements; when Turchill, the then vicomes of Warwick, was ordered by that monarch to enlarge and repair it. The Conqueror, however, being distrustful of Turchill, committed the custody of it to one of his own followers, Henry de Newburgh, whom he created Earl of Warwick, the first of that title of the Norman line. The stately building at the north-east angle, called Guy's Tower, was erected in the year 1394, by Thomas Beauchamp, the son and successor of the first earl of that family, and was so called in honour of the ancient hero of that name, and also one of the earls of Warwick. It is 128 feet in height, and the walls, which are of solid masonry, measure 10 feet in thickness. Cæsar's Tower, which is supposed to be the most ancient part of the fabric, is 147 feet in height; but appears to be less lofty than that of Guy's, from its being situated on a less elevated part of the rock.

In the reign of Henry III., Warwick Castle was of such importance, that security was required from Margery, the sister and heiress of Thomas de Newburgh, the sixth earl of the Norman line, that she would not marry with any person in whom the king could not place the greatest confidence. During the same reign, in the year 1265, William Manduit, who had garrisoned the castle on the side of the king against the rebellious barons, was surprised by John Gifford, the governor of Kenilworth Castle, who, having destroyed a great part of the walls, took him, together with the countess, his wife, prisoners; and a ransom of nineteen hundred marks were paid, before their release could be obtained. The last attack which it sustained was during the civil wars in the seventeenth century, when it was besieged for a fortnight, but did not surrender.

Few persons have made a greater figure in history than the earls of Warwick, from the renowned

—– Sir Guy of Warwicke, as was wetenIn palmer wyse, as Colman hath it wryten;The battaill toke on hym for Englandis right,With the Colbrond in armes for to fight.4up to the accomplished Sir Fulk Greville, to whom the castle, with all its dependencies, was granted by James I., after having passed through the successive lines of Beauchamp, Neville, Plantagenet, and Dudley.

L.L.

ODE TO THE LONDON STONE

(For the Mirror.)Mound of antiquity's dark hidden ways,Though long thou'st slumber'd in thy holy niche,Now, the first time, a modern bard essaysTo crave thy primal use, the what and which!Speak! break my sorry ignorance asunder!City stone-henge, of aldermanic wonder.Wert them a fragment of a Druid pile,Some glorious throne of early British art?Some trophy worthy of our rising isle,Soon from its dull obscurity to start.Wert thou an altar for a world's respect?Now the sole remnant of thy fame and sect.Wert thou a churchyard ornament, to braidThe charnel of putridity, and partThe spot where what was mortal had been laid,With all thy native coldness in his heart?Thou sure wert not the stone—let critics cavil!—Of quack M.D. who lectur'd on the gravel.Did e'er fat Falstaff, wreathing 'neath his cupOf glorious sack, unable to reel home,Sit on thy breast, and give his fancy up,The all that wine had given pow'r to roam,And left the mind in gay, but dreamy talk,Wakeful in wit when legs denied to walk?Did e'er wise Shakspeare brood upon thy mass,And whimsey thee to any wondrous useOf sage forefathers, in his verse to classThat which a worse bard had despis'd to choose,Unconscious how the meanest objects grow,Giants of notice in the poet's show?Canst thou not tell a tale of varied life,That gave Time's annals their recording name?No notes of Cade, marching with mischief rife,By Britain's misery to raise his fame?Wert thou the hone that "City's Lord" essay'd5To make the whetstone of his rebel blade?Wert thou—'tis pleasant to imagine it,Howe'er absurd such notions may be thought—When the wide heavens, wild with thunder fit,Huge hailstones to distress the nation wrought,A mass congeal'd of heaven's artill'ry wain,6A "hailstone chorus" of a Mary's reign?Or, wert thou part of monumental shrineRais'd to a genius, who, for daily bread,While living, the base world had left to pine,Only to find his value out when dead?Say, wert thou any such memento lone,Of bard who wrote for bread, and got a stone?How many nations slumber on their deeds.The all that's left them of their mighty race?How may heroes' bosoms, wars, and creedsHave sought in stilly death a resting place,Since thou first gave thy presence to the air,Thou, who art looking scarce the worse for wear!Oft may each wave have travell'd to the shore,That ends the vasty ocean's unknown sway,Since thou wert first from earth's remotest pore,Rais'd as an emblem of man's craft to lay;Yet those same waves shall dwindle into earth,Ere, lost in time, we learn thy primal worth.They tell us "walls have ears"—then why, forsooth,Hast thou no tongue, like ancient stones of Rome,To paint the gory days of Britain's youth,And what thou wert when viler was thy home?Man makes thy kindred record of his name—Hast thou no tongue to historize thy fame?But thou! O, thou hast nothing to repeat!Lump of mysteriousness, the hand of TimeNo early pleasures from thy breast could cheat,Or witness in decay thine early prime!Yes, thou didst e'er in stony slumbers lay,Defying each M'Adam of his day.Eternity of stone! Time's lasting shrine!Whose minutes shall by thee unheeded pour!With whom in still companionship thou'lt twineThe past, the present, shall be evermore,While innate strength shall shield thee from his hurt,And worlds remain stone blind to what thou wert.P.T.

THE NECK. 7

A SWEDISH TRADITION

(For the Mirror.)His cheek was blanch'd, but beautiful and soft, each curling tressWav'd round the harp, o'er which he bent with zephyrine caress;And as that lyrist sat all lorn, upon the silv'ry stream,The music of his harp was as the music of a dream,Most mournfully delicious, like those tones that wound the heart,Yet soothe it, when it cherishes the griefs that ne'er depart."O Neck! O water-spirit! demon, delicate, and fair!"The young twain cried, who heard his lay, "why art thou harping there?Thine airy form is drooping, Neck! thy cheek is pale with dree,And torrents shouldst thou weep, poor fay, no Saviour lives for thee!"All mournful look'd the elflet then, and sobbing, cast asideHis harp, and with a piteous wail, sunk fathoms in the tide.Keen sorrow seiz'd those gentle youths, who'd given cureless pain—In haste they sought their priestly sire, in haste return'd again;Return'd to view the elf enthron'd in waters as before,Whose music now was sighs, whose tears gush'd e'en from his heart's core."Why weeping, Neck? look up, and clear those tearful eyes of blue—Our father bids us say, that thy Redeemer liveth too!"Oh, beautiful! blest words! they sooth'd the Nikkar's anguish'd breast,As breezy, angel-whisperings lull holy ones to rest.He seiz'd his harp—its airy strings, beneath a master hand,Woke melodies, too, too divine for earth or elfin land;He rais'd his glad, rich voice in song, and sinking saw the sun,Ere in that hymn of love he paus'd, for Paradise begun!M.L.B.PLAN FOR SNUFF TAKERS TO PAY OFF THE NATIONAL DEBT

(For the Mirror.)As snuff-taking seems to increase, the following plan might be adopted by the patrons of that art, to ease John Bull of his weight, and make him feel as light and easy, as if he had taken a pinch of the "Prince Regent's Mixture.'"

Lord Stanhope says, "Every professed, inveterate, and incurable snuff-taker, at a moderate computation, takes one pinch in ten minutes. Every pinch, with the agreeable ceremony of blowing and wiping the nose, and other incidental circumstances, consumes a minute and a half. One minute and a half out of every ten, allowing sixteen hours and a half to a snuff-taking day, amounts to two hours and twenty-four minutes out of every natural day, or one day out of every ten. One day out of every ten amounts to thirty-six days and a half in a-year. Hence, if we suppose the practice to be persisted in forty years, two entire years of the snuff-taker's life will be dedicated to tickling his nose, and two more to blowing it. The expense of snuff, snuff-boxes, and handkerchiefs, will be the subject of a second essay, in which it will appear, that this luxury encroaches as much on the income of the snuff-taker as it does on his time; and that by a proper application of the time and money thus lost to the public, a fund might be constituted for the discharge of the national debt."

Queries.—Is not this subject worthy the attention of the finance committee? Might not the cigar gentlemen add to the discharge of the debt?

P.T.W.

THE DIVIDED HOUSEHOLD

(For the Mirror.)Our hearth—we hear its music now—to us a bower and home;When will its lustre in our souls with Spring's young freshness come?Sweet faces beam'd around it then, and cherub lips did weaveTheir clear Hosannas in the glow that ting'd the skies at eve!Oh, lonely is our forest stream, and bare the woodland tree,And whose sunny wreath of leaves the cuckoo carolled free;The pilgrim passeth by our cot—no hand shall greet him there—The household is divided now, and mute the evening pray'r!Amid green walks and fringed slopes, still gleams the village pond.And see, a hoar and sacred pile, the old church peers beyond;And there we deem'd it bliss to gaze upon the Sabbath skies,—Gold as our sister's clustering hair, and blue as her meek eyes.Our home—when will these eyes, now dimm'd with frequent weeping, seeThe infant's pure and rosy ark, the stripling's sanctuary?When will these throbbing hearts grow calm around its lighted hearth?—Quench'd is the fire within its walls, and hush'd the voice of mirth!The haunts—they are forsaken now—where our companions play'd;We see their silken ringlets glow amid the moonlight glade;We hear their voices floating up like pæan songs divine;Their path is o'er the violet-beds beneath the springing vine!Restore, sweet spirit of our home! our native hearth restore—Why are our bosoms desolate, our summer rambles o'er?Let thy mild light on us be pour'd—our raptures kindle up,And with a portion of thy bliss illume the household cup.Yet mourn not, wanderers—onto you a thrilling hope is given,A tabernacle unconfin'd, an endless home in heaven!And though ye are divided now, ye shall be made as oneIn Eden, beauteous as the skies that o'er your childhood shone!Deal.

REGINALD AUGUSTINE.

A CHAPTER ON KISSING

BY A PROFESSOR OF THE ART(For the Mirror.)"Away with your fictions of flimsy romance,Those tissues of falsehood which folly has wove;Give me the mild gleam of the soul breathing glance,And the rapture which dwells in the first kiss of love."BYRON.There is no national custom so universally and so justly honoured with esteem and respect, "winning golden opinions from all sorts of people," as kissing. Generally speaking, we discover that a usage which finds favour in the eyes of the vulgar, is despised and detested by the educated, the refined, and the proud; but this elegant practice forms a brilliant exception to a rule otherwise tolerably absolute. Kissing possesses infinite claims to our love, claims which no other custom in the wide world can even pretend to advance. Kissing is an endearing, affectionate, ancient, rational, and national mode of displaying the thousand glowing emotions of the soul;—it is traced back by some as far as the termination of the siege of Troy, for say they, "Upon the return of the Grecian warriors, their wives met them, and joined their lips together with joy." There are some, however, who give the honour of having invented kissing to Rouix, or Rowena, the daughter of Hengist, the Saxon; a Dutch historian tells us, she, "pressed the beaker with her lipkens (little lips,) and saluted the amorous Vortigern with a husgin (little kiss,)" and this latter authority we ourselves feel most inclined to rely on; deeply anxious to secure to our fair countrywomen the honour of having invented this delightful art.

Numberless are the authors who have written and spoken with rapture on English kissing.

"The women of England," says Polydore Virgil, "not only salute their relations with a kiss, but all persons promiscuously; and this ceremony they repeat, gently touching them with their lips, not only with grace, but without the least immodesty. Such, however, as are of the blood-royal do not kiss their inferiors, but offer the back of the hand, as men do, by way of saluting each other."

Erasmus too—the grave, the phlegmatic Erasmus, melts into love and playful thoughts, when he thinks of kisses—"Did you but know, my Faustus," he writes to one of his friends, "the pleasures which England affords, you would fly here on winged feet, and if your gout would not allow you, you would wish yourself a Dædalus. To mention to you one among many things, here are nymphs of the loveliest looks, good humoured, and whom you would prefer even to your favourite Muses. Here also prevails a custom never enough to be commended, that wherever you come, every one receives you with a kiss, and when you take your leave, every one gives you a kiss; when you return, kisses again meet you. If any one leaves you they give you a kiss; if you meet any one, the first salutation is a kiss; in short, wherever you go, kisses every where abound; which, my Faustus, did you once taste how very sweet and how very fragrant they are, you would not, like Solon, wish for ten years exile in England, but would desire to spend there the whole of your life."

Oh what miracles have been wrought by a kiss! Philosophers, stoics, hermits, and misers have become men of the world, of taste, and of generosity; idiots have become wise; and, truth to tell, wise men idiots—warriors have turned cowards and cowards brave—statesmen have become poets, and political economists sensible men. Oh, wonderful art, which can produce such strange effects! to thee, the magic powers of steam seem commonplace and tedious; the wizard may break his rod in despair, and the king his sceptre, for thou canst effect in a moment what they may vainly labour years to accomplish. Well may the poet celebrate thy praises in words that breathe and thoughts that burn; well may the minstrel fire with sudden inspiration and strike the lute with rapture when he thinks of thee; well might the knight of bygone times brave every danger when thou wert his bright reward; well might Vortigern resign his kingdom, or Mark Antony the world, when it was thee that tempted. Long, long, may England be praised for her prevalence of this divine custom! Long may British women be as celebrated for the fragrance of their kisses, as they ever were, and ever will be for their virtue and their beauty.

CHILDE WILFUL.

Notes of a Reader

"COMPANION TO THE THEATRES."

An inveterate play-goer announces a little manual under this title, for publication in a few days. Such a work, if well executed, will be very acceptable to the amateur and visitor, as well as attractive to the general reader. The outline or plan looks well, and next week we may probably give our readers some idea of its execution.

VOYAGE TO INDIA

The generality of our society on board was respectable, and some of its members were men of education and talent. Excepting that there was no lady of the party, it was composed of the usual materials to be found at the cuddy-table of an outward bound Indiaman. First, there was a puisne judge, intrenched in all the dignity of a dispenser of law to his majesty's loving subjects beyond the Cape, with a Don't tell me kind of face, a magisterial air, and dictatorial manner, ever more ready to lay down the law, than to lay down the lawyer. Then, there was a general officer appointed to the staff in India, in consideration of his services on Wimbledon Common and at the Horse Guards, proceeding to teach the art military to the Indian army—a man of gentlemanly but rather pompous manners; who, considering his simple nod equivalent to the bows of half a dozen subordinates, could never swallow a glass of wine at dinner without lumping at least that number of officers or civilians in the invitation to join him, while his aid-de-camp practised the same airs among the cadets. Then, there was a proportion of civilians and Indian officers returning from furlough or sick certificate, with patched-up livers, and lank countenances, from which two winters of their native climate had extracted only just sufficient sunbeams to leave them of a dirty lemon colour. Next, there were a few officers belonging to detachments of king's troops proceeding to join their regiments in India, looking, of course, with some degree of contempt on their brethren in arms, whose rank was bounded by the longitude of the Cape; but condescending to patronize some of the most gentlemanly of the cadets. These, with a free mariner, and no inconsiderable sprinkling of writers, cadets, and assistant-surgeons, together with the officers of the ship, who dined at the captain's table, formed a party of about twenty-five.—Twelve Years' Military Adventure.

EDUCATION IN DENMARK

Much pains has lately been taken in Denmark to promote the means of elementary education, and Lancasterian schools have been generally established throughout the country. We have now before us the Report made to the king by the Chevalier Abrahamson, of the progress, prospects, and present state of the schools for mutual instruction in Denmark, to the 28th of January, 1828, by which it appears, that 2,371 schools for mutual instruction have been established, and are in full progress, in the different districts of the kingdom and in the army. —North American Review.

RECORDS

Some faint idea of the bulk of our English records may be obtained, by adverting to the fact, that a single statute, the Land Tax Commissioners' Act, passed in the first year of the reign of his present majesty, measures, when unrolled, upwards of nine hundred feet, or nearly twice the length of St. Paul's Cathedral within the walls; and if it ever should become necessary to consult the fearful volume, an able-bodied man must be employed during three hours in coiling and uncoiling its monstrous folds. Should our law manufactory go on at this rate, and we do not anticipate any interruption in its progress, we may soon be able to belt the round globe with parchment. When, to the solemn acts of legislature, we add the showers of petitions, which lie (and in more senses than one) upon the table, every night of the session; the bills, which, at the end of every term, are piled in stacks, under the parental custody of our good friends, the Six Clerks in Chancery; and the innumerable membranes, which, at every hour of the day, are transmitted to the gloomy dens and recesses of the different courts of common-law and of criminal jurisdiction throughout the kingdom, we are afraid that there are many who may think that the time is fast approaching for performing the operation which Hugh Peters recommended as "A good work for a good Magistrate." This learned person, it will be recollected, exhorted the commonwealth men to destroy all the muniments in the Tower—a proposal which Prynne considers as an act inferior only in atrocity to his participation in the murder of Charles I., and we should not be surprised if some zealous reformer were to maintain, that a general conflagration of these documents would be the most essential benefit that could be conferred upon the realm.—Quarterly Rev.

ENCYCLOPÆDIAS

In the German universities an extensive branch of lectures is formed by the Encyclopædias of the various sciences. Encyclopædia originally implied the complete course or circle of a liberal education in science and art, as pursued by the young men of Greece; namely, gymnastics, a cultivated taste for their own classics, music, arithmetic, and geometry. European writers give the name of encyclopædia, in the widest scientific sense, to the whole round or empire of human knowledge, arranged in systematic or alphabetic order; whereas the Greek imports but practical school knowledge. The literature of the former is voluminous beyond description, it having been cultivated from the beginning of the middle ages to the present day. Different from either of them is the encyclopædia of the German universities; this is an introduction into the several arts and sciences, showing the nature of each, its extent, utility, relation to other studies and to practical life, the best method of pursuing it, and the sources from whence the knowledge of it is to be derived. An introduction of this compass is, however, with greater propriety styled encyclopædia and methodology. Thus, we hear of separate lectures on encyclopædias and methodologies of divinity, jurisprudence, medicine, philosophy, mathematical sciences, physical science, the fine arts, and philology. Manuals and lectures of this kind are exceedingly useful for those who are commencing a course of professional study. For "the best way to learn any science," says Watts, "is to begin with a regular system, or a short and plain scheme of that science, well drawn up into a narrow compass."—Ibid.