полная версия

полная версияFrance and England in North America, Part VI : Montcalm and Wolfe

Thither the troops advanced, marched by files till they reached the ground, and then wheeled to form their line of battle, which stretched across the plateau and faced the city. It consisted of six battalions and the detached grenadiers from Louisbourg, all drawn up in ranks three deep. Its right wing was near the brink of the heights along the St. Lawrence; but the left could not reach those along the St. Charles. On this side a wide space was perforce left open, and there was danger of being outflanked. To prevent this, Brigadier Townshend was stationed here with two battalions, drawn up at right angles with the rest, and fronting the St. Charles. The battalion of Webb's regiment, under Colonel Burton, formed the reserve; the third battalion of Royal Americans was left to guard the landing; and Howe's light infantry occupied a wood far in the rear. Wolfe, with Monckton and Murray, commanded the front line, on which the heavy fighting was to fall, and which, when all the troops had arrived, numbered less than thirty-five hundred men.778

Quebec was not a mile distant, but they could not see it; for a ridge of broken ground intervened, called Buttes-à-Neveu, about six hundred paces off. The first division of troops had scarcely come up when, about six o'clock, this ridge was suddenly thronged with white uniforms. It was the battalion of Guienne, arrived at the eleventh hour from its camp by the St. Charles. Some time after there was hot firing in the rear. It came from a detachment of Bougainville's command attacking a house where some of the light infantry were posted. The assailants were repulsed, and the firing ceased. Light showers fell at intervals, besprinkling the troops as they stood patiently waiting the event.

Montcalm had passed a troubled night. Through all the evening the cannon bellowed from the ships of Saunders, and the boats of the fleet hovered in the dusk off the Beauport shore, threatening every moment to land. Troops lined the intrenchments till day, while the General walked the field that adjoined his headquarters till one in the morning, accompanied by the Chevalier Johnstone and Colonel Poulariez. Johnstone says that he was in great agitation, and took no rest all night. At daybreak he heard the sound of cannon above the town. It was the battery at Samos firing on the English ships. He had sent an officer to the quarters of Vaudreuil, which were much nearer Quebec, with orders to bring him word at once should anything unusual happen. But no word came, and about six o'clock he mounted and rode thither with Johnstone. As they advanced, the country behind the town opened more and more upon their sight; till at length, when opposite Vaudreuil's house, they saw across the St. Charles, some two miles away, the red ranks of British soldiers on the heights beyond.

"This is a serious business," Montcalm said; and sent off Johnstone at full gallop to bring up the troops from the centre and left of the camp. Those of the right were in motion already, doubtless by the Governor's order. Vaudreuil came out of the house. Montcalm stopped for a few words with him; then set spurs to his horse, and rode over the bridge of the St. Charles to the scene of danger.779 He rode with a fixed look, uttering not a word.780

The army followed in such order as it might, crossed the bridge in hot haste, passed under the northern rampart of Quebec, entered at the Palace Gate, and pressed on in headlong march along the quaint narrow streets of the warlike town: troops of Indians in scalplocks and war-paint, a savage glitter in their deep-set eyes; bands of Canadians whose all was at stake,—faith, country, and home; the colony regulars; the battalions of Old France, a torrent of white uniforms and gleaming bayonets, La Sarre, Languedoc, Roussillon, Béarn,—victors of Oswego, William Henry, and Ticonderoga. So they swept on, poured out upon the plain, some by the gate of St. Louis, and some by that of St. John, and hurried, breathless, to where the banners of Guienne still fluttered on the ridge.

Montcalm was amazed at what he saw. He had expected a detachment, and he found an army. Full in sight before him stretched the lines of Wolfe: the close ranks of the English infantry, a silent wall of red, and the wild array of the Highlanders, with their waving tartans, and bagpipes screaming defiance. Vaudreuil had not come; but not the less was felt the evil of a divided authority and the jealousy of the rival chiefs. Montcalm waited long for the forces he had ordered to join him from the left wing of the army. He waited in vain. It is said that the Governor had detained them, lest the English should attack the Beauport shore. Even if they did so, and succeeded, the French might defy them, could they but put Wolfe to rout on the Plains of Abraham. Neither did the garrison of Quebec come to the aid of Montcalm. He sent to Ramesay, its commander, for twenty-five field-pieces which were on the Palace battery. Ramesay would give him only three, saying that he wanted them for his own defence. There were orders and counter-orders; misunderstanding, haste, delay, perplexity.

Montcalm and his chief officers held a council of war. It is said that he and they alike were for immediate attack. His enemies declare that he was afraid lest Vaudreuil should arrive and take command; but the Governor was not a man to assume responsibility at such a crisis. Others say that his impetuosity overcame his better judgment; and of this charge it is hard to acquit him. Bougainville was but a few miles distant, and some of his troops were much nearer; a messenger sent by way of Old Lorette could have reached him in an hour and a half at most, and a combined attack in front and rear might have been concerted with him. If, moreover, Montcalm could have come to an understanding with Vaudreuil, his own force might have been strengthened by two or three thousand additional men from the town and the camp of Beauport; but he felt that there was no time to lose, for he imagined that Wolfe would soon be reinforced, which was impossible, and he believed that the English were fortifying themselves, which was no less an error. He has been blamed not only for fighting too soon, but for fighting at all. In this he could not choose. Fight he must, for Wolfe was now in a position to cut off all his supplies. His men were full of ardor, and he resolved to attack before their ardor cooled. He spoke a few words to them in his keen, vehement way. "I remember very well how he looked," one of the Canadians, then a boy of eighteen, used to say in his old age; "he rode a black or dark bay horse along the front of our lines, brandishing his sword, as if to excite us to do our duty. He wore a coat with wide sleeves, which fell back as he raised his arm, and showed the white linen of the wristband."781

The English waited the result with a composure which, if not quite real, was at least well feigned. The three field-pieces sent by Ramesay plied them with canister-shot, and fifteen hundred Canadians and Indians fusilladed them in front and flank. Over all the plain, from behind bushes and knolls and the edge of cornfields, puffs of smoke sprang incessantly from the guns of these hidden marksmen. Skirmishers were thrown out before the lines to hold them in check, and the soldiers were ordered to lie on the grass to avoid the shot. The firing was liveliest on the English left, where bands of sharpshooters got under the edge of the declivity, among thickets, and behind scattered houses, whence they killed and wounded a considerable number of Townshend's men. The light infantry were called up from the rear. The houses were taken and retaken, and one or more of them was burned.

Wolfe was everywhere. How cool he was, and why his followers loved him, is shown by an incident that happened in the course of the morning. One of his captains was shot through the lungs; and on recovering consciousness he saw the General standing at his side. Wolfe pressed his hand, told him not to despair, praised his services, promised him early promotion, and sent an aide-de-camp to Monckton to beg that officer to keep the promise if he himself should fall.782

It was towards ten o'clock when, from the high ground on the right of the line, Wolfe saw that the crisis was near. The French on the ridge had formed themselves into three bodies, regulars in the centre, regulars and Canadians on right and left. Two field-pieces, which had been dragged up the heights at Anse du Foulon, fired on them with grape-shot, and the troops, rising from the ground, prepared to receive them. In a few moments more they were in motion. They came on rapidly, uttering loud shouts, and firing as soon as they were within range. Their ranks, ill ordered at the best, were further confused by a number of Canadians who had been mixed among the regulars, and who, after hastily firing, threw themselves on the ground to reload.783 The British advanced a few rods; then halted and stood still. When the French were within forty paces the word of command rang out, and a crash of musketry answered all along the line. The volley was delivered with remarkable precision. In the battalions of the centre, which had suffered least from the enemy's bullets, the simultaneous explosion was afterwards said by French officers to have sounded like a cannon-shot. Another volley followed, and then a furious clattering fire that lasted but a minute or two. When the smoke rose, a miserable sight was revealed: the ground cumbered with dead and wounded, the advancing masses stopped short and turned into a frantic mob, shouting, cursing, gesticulating. The order was given to charge. Then over the field rose the British cheer, mixed with the fierce yell of the Highland slogan. Some of the corps pushed forward with the bayonet; some advanced firing. The clansmen drew their broadswords and dashed on, keen and swift as bloodhounds. At the English right, though the attacking column was broken to pieces, a fire was still kept up, chiefly, it seems, by sharpshooters from the bushes and cornfields, where they had lain for an hour or more. Here Wolfe himself led the charge, at the head of the Louisbourg grenadiers. A shot shattered his wrist. He wrapped his handkerchief about it and kept on. Another shot struck him, and he still advanced, when a third lodged in his breast. He staggered, and sat on the ground. Lieutenant Brown, of the grenadiers, one Henderson, a volunteer in the same company, and a private soldier, aided by an officer of artillery who ran to join them, carried him in their arms to the rear. He begged them to lay him down. They did so, and asked if he would have a surgeon. "There's no need," he answered; "it's all over with me." A moment after, one of them cried out: "They run; see how they run!" "Who run?" Wolfe demanded, like a man roused from sleep. "The enemy, sir. Egad, they give way everywhere!" "Go, one of you, to Colonel Burton," returned the dying man; "tell him to march Webb's regiment down to Charles River, to cut off their retreat from the bridge." Then, turning on his side, he murmured, "Now, God be praised, I will die in peace!" and in a few moments his gallant soul had fled.

Montcalm, still on horseback, was borne with the tide of fugitives towards the town. As he approached the walls a shot passed through his body. He kept his seat; two soldiers supported him, one on each side, and led his horse through the St. Louis Gate. On the open space within, among the excited crowd, were several women, drawn, no doubt, by eagerness to know the result of the fight. One of them recognized him, saw the streaming blood, and shrieked, "O mon Dieu! mon Dieu! le Marquis est tué!" "It's nothing, it's nothing," replied the death-stricken man; "don't be troubled for me, my good friends." ("Ce n'est rien, ce n'est rien; ne vous affligez pas pour moi, mes bonnes amies.")

Note.—There are several contemporary versions of the dying words of Wolfe. The report of Knox, given above, is by far the best attested. Knox says that he took particular pains at the time to learn them accurately from those who were with Wolfe when they were uttered.

The anecdote of Montcalm is due to the late Hon. Malcolm Fraser, of Quebec. He often heard it in his youth from an old woman, who, when a girl, was one of the group who saw the wounded general led by, and to whom the words were addressed.

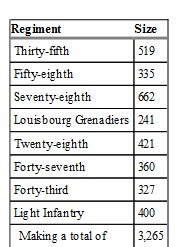

Force of the English and French at the Battle of Quebec.—The tabular return given by Knox shows the number of officers and men in each corps engaged. According to this, the battalions as they stood on the Plains of Abraham before the battle varied in strength from 322 (Monckton's) to 683 (Webb's), making a total of 4,828, including officers. But another return, less specific, signed George Townshend, Brigadier, makes the entire number only 4,441. Townshend succeeded Wolfe in the command; and this return, which is preserved in the Public Record Office, was sent to London a few days after the battle. Some French writers present put the number lower, perhaps for the reason that Webb's regiment and the third battalion of Royal Americans took no part in the fight, the one being in the rear as a reserve, and the other also invisible, guarding the landing place. Wolfe's front line, which alone met and turned the French attack, was made up as follows, the figures including officers and men:—

The French force engaged cannot be precisely given. Knox, on information received from "an intelligent Frenchman," states the number, corps by corps, the aggregate being 7,520. This, on examination, plainly appears exaggerated. Fraser puts it at 5,000; Townshend at 4,470, including militia. Bigot says, 3,500, which may perhaps be as many as actually advanced to the attack, since some of the militia held back. Including Bougainville's command, the militia and the artillerymen left in the Beauport camp, the sailors at the town batteries, and the garrison of Quebec, at least as many of the French were out of the battle as were in it; and the numbers engaged on each side seem to have been about equal.

For authorities of the foregoing chapter, seeAppendix I.

CHAPTER XXVIII.

1759

FALL OF QUEBECAfter the Battle • Canadians resist the Pursuit • Arrival of Vaudreuil • Scene in the Redoubt • Panic • Movements of the Victors • Vaudreuil's Council of War • Precipitate Retreat of the French Army • Last Hours of Montcalm • His Death and Burial • Quebec abandoned to its Fate • Despair of the Garrison • Lévis joins the Army • Attempts to relieve the Town • Surrender • The British occupy Quebec • Slanders of Vaudreuil • Reception in England of the News of Wolfe's Victory and Death • Prediction of Jonathan Mayhew.

"Never was rout more complete than that of our army," says a French official.784 It was the more so because Montcalm held no troops in reserve, but launched his whole force at once against the English. Nevertheless there was some resistance to the pursuit. It came chiefly from the Canadians, many of whom had not advanced with the regulars to the attack. Those on the right wing, instead of doing so, threw themselves into an extensive tract of bushes that lay in front of the English left; and from this cover they opened a fire, too distant for much effect, till the victors advanced in their turn, when the shot of the hidden marksmen told severely upon them. Two battalions, therefore, deployed before the bushes, fired volleys into them, and drove their occupants out.

Again, those of the Canadians who, before the main battle began, attacked the English left from the brink of the plateau towards the St. Charles, withdrew when the rout took place, and ran along the edge of the declivity till, at the part of it called Côte Ste.-Geneviève, they came to a place where it was overgrown with thickets. Into these they threw themselves; and were no sooner under cover than they faced about to fire upon the Highlanders, who presently came up. As many of these mountaineers, according to their old custom, threw down their muskets when they charged, and had no weapons but their broadswords, they tried in vain to dislodge the marksmen, and suffered greatly in the attempt. Other troops came to their aid, cleared the thickets, after stout resistance, and drove their occupants across the meadow to the bridge of boats. The conduct of the Canadians at the Côte Ste.-Geneviève went far to atone for the shortcomings of some of them on the battle-field.

A part of the fugitives escaped into the town by the gates of St. Louis and St. John, while the greater number fled along the front of the ramparts, rushed down the declivity to the suburb of St. Roch, and ran over the meadows to the bridge, protected by the cannon of the town and the two armed hulks in the river. The rout had but just begun when Vaudreuil crossed the bridge from the camp of Beauport. It was four hours since he first heard the alarm, and his quarters were not much more than two miles from the battle-field. He does not explain why he did not come sooner; it is certain that his coming was well timed to throw the blame on Montcalm in case of defeat, or to claim some of the honor for himself in case of victory. "Monsieur the Marquis of Montcalm," he says, "unfortunately made his attack before I had joined him."785 His joining him could have done no good; for though he had at last brought with him the rest of the militia from the Beauport camp, they had come no farther than the bridge over the St. Charles, having, as he alleges, been kept there by an unauthorized order from the chief of staff, Montreuil.786 He declares that the regulars were in such a fright that he could not stop them; but that the Canadians listened to his voice, and that it was he who rallied them at the Côte Ste.-Geneviève. Of this the evidence is his own word. From other accounts it would appear that the Canadians rallied themselves. Vaudreuil lost no time in recrossing the bridge and joining the militia in the redoubt at the farther end, where a crowd of fugitives soon poured in after him.

The aide-de-camp Johnstone, mounted on horseback, had stopped for a moment in what is now the suburb of St. John to encourage some soldiers who were trying to save a cannon that had stuck fast in a marshy hollow; when, on spurring his horse to the higher ground, he saw within musket-shot a long line of British troops, who immediately fired upon him. The bullets whistled about his ears, tore his clothes, and wounded his horse; which, however, carried him along the edge of the declivity to a windmill, near which was a roadway to a bakehouse on the meadow below. He descended, crossed the meadow, reached the bridge, and rode over it to the great redoubt or hornwork that guarded its head.

The place was full of troops and Canadians in a wild panic. "It is impossible," says Johnstone, "to imagine the disorder and confusion I found in the hornwork. Consternation was general. M. de Vaudreuil listened to everybody, and was always of the opinion of him who spoke last. On the appearance of the English troops on the plain by the bakehouse, Montguet and La Motte, two old captains in the regiment of Béarn, cried out with vehemence to M. de Vaudreuil 'that the hornwork would be taken in an instant by assault, sword in hand; that we all should be cut to pieces without quarter; and that nothing would save us but an immediate and general capitulation of Canada, giving it up to the English.'"787 Yet the river was wide and deep, and the hornwork was protected on the water side by strong palisades, with cannon. Nevertheless there rose a general cry to cut the bridge of boats. By doing so more than half the army, who had not yet crossed, would have been sacrificed. The axemen were already at work, when they were stopped by some officers who had not lost their wits.

"M. de Vaudreuil," pursues Johnstone, "was closeted in a house in the inside of the hornwork with the Intendant and some other persons. I suspected they were busy drafting the articles for a general capitulation, and I entered the house, where I had only time to see the Intendant, with a pen in his hand, writing upon a sheet of paper, when M. de Vaudreuil told me I had no business there. Having answered him that what he had said was true, I retired immediately, in wrath to see them intent on giving up so scandalously a dependency for the preservation of which so much blood and treasure had been expended." On going out he met Lieutenant-colonels Dalquier and Poulariez, whom he begged to prevent the apprehended disgrace; and, in fact, if Vaudreuil really meant to capitulate for the colony, he was presently dissuaded by firmer spirits than his own.

Johnstone, whose horse could carry him no farther, set out on foot for Beauport, and, in his own words, "continued sorrowfully jogging on, with a very heavy heart for the loss of my dear friend M. de Montcalm, sinking with weariness, and lost in reflection upon the changes which Providence had brought about in the space of three or four hours."

Great indeed were these changes. Montcalm was dying; his second in command, the Brigadier Senezergues, was mortally wounded; the army, routed and demoralized, was virtually without a head; and the colony, yesterday cheered as on the eve of deliverance, was plunged into sudden despair. "Ah, what a cruel day!" cries Bougainville; "how fatal to all that was dearest to us! My heart is torn in its most tender parts. We shall be fortunate if the approach of winter saves the country from total ruin."788

The victors were fortifying themselves on the field of battle. Like the French, they had lost two generals; for Monckton, second in rank, was disabled by a musket-shot, and the command had fallen upon Townshend at the moment when the enemy were in full flight. He had recalled the pursuers, and formed them again in line of battle, knowing that another foe was at hand. Bougainville, in fact, appeared at noon from Cap-Rouge with about two thousand men; but withdrew on seeing double that force prepared to receive him. He had not heard till eight o'clock that the English were on the Plains of Abraham; and the delay of his arrival was no doubt due to his endeavors to collect as many as possible of his detachments posted along the St. Lawrence for many miles towards Jacques-Cartier.

Before midnight the English had made good progress in their redoubts and intrenchments, had brought cannon up the heights to defend them, planted a battery on the Côte Ste.-Geneviève, descended into the meadows of the St. Charles, and taken possession of the General Hospital, with its crowds of sick and wounded. Their victory had cost them six hundred and sixty-four of all ranks, killed, wounded, and missing. The French loss is placed by Vaudreuil at about six hundred and forty, and by the English official reports at about fifteen hundred. Measured by the numbers engaged, the battle of Quebec was but a heavy skirmish; measured by results, it was one of the great battles of the world.

Vaudreuil went from the hornwork to his quarters on the Beauport road and called a council of war. It was a tumultuous scene. A letter was despatched to Quebec to ask advice of Montcalm. The dying General sent a brief message to the effect that there was a threefold choice,—to fight again, retreat to Jacques-Cartier, or give up the colony. There was much in favor of fighting. When Bougainville had gathered all his force from the river above, he would have three thousand men; and these, joined to the garrison of Quebec, the sailors at the batteries, and the militia and artillerymen of the Beauport camp, would form a body of fresh soldiers more than equal to the English then on the Plains of Abraham. Add to these the defeated troops, and the victors would be greatly outnumbered.789 Bigot gave his voice for fighting. Vaudreuil expressed himself to the same effect; but he says that all the officers were against him. "In vain I remarked to these gentlemen that we were superior to the enemy, and should beat them if we managed well. I could not at all change their opinion, and my love for the service and for the colony made me subscribe to the views of the council. In fact, if I had attacked the English against the advice of all the principal officers, their ill-will would have exposed me to the risk of losing the battle and the colony also."790

It was said at the time that the officers voted for retreat because they thought Vaudreuil unfit to command an army, and, still more, to fight a battle.791 There was no need, however, to fight at once. The object of the English was to take Quebec, and that of Vaudreuil should have been to keep it. By a march of a few miles he could have joined Bougainville; and by then intrenching himself at or near Ste.-Foy he would have placed a greatly superior force in the English rear, where his position might have been made impregnable. Here he might be easily furnished with provisions, and from hence he could readily throw men and supplies into Quebec, which the English were too few to invest. He could harass the besiegers, or attack them, should opportunity offer, and either raise the siege or so protract it that they would be forced by approaching winter to sail homeward, robbed of the fruit of their victory.