полная версия

полная версияThe Mirror Of Literature, Amusement, And Instruction. Volume 14, No. 391, September 26, 1829

"It is one of the proudest attributes of man, and one which is most important for him to know, that he can improve every production of nature, if he will but once make it his own by possession and attachment. A conviction of this truth has rendered the cultivation of fruits, in the more polished countries of Europe, as successful as we now behold it."

The work then divides into Fruits of the Temperate Climates, and of Tropical Climates; the first are subdivided into Fleshy, Pulpy, and Stone Fruits and Nuts, in preference to a strict geographical arrangement. Under "the Apple" occur some very judicious observations on

Cider"The cider counties of England have always been considered as highly interesting. They lie something in the form of a horse-shoe round the Bristol Channel; and the best are, Worcester and Hereford, on the north of the channel, and Somerset and Devon on the south. In appearance, they have a considerable advantage over those counties in which grain alone is cultivated. The blossoms cover an extensive district with a profusion of flowers in the spring, and the fruit is beautiful in autumn. Some of the orchards occupy a space of forty or fifty acres; and the trees being at considerable intervals, the land is also kept in tillage. A great deal of practical acquaintance with the qualities of soil is required in the culture of apple and pear trees; and his skill in the adaptation of trees to their situation principally determines the success of the manufacturer of cider and perry. The produce of the orchards is very fluctuating; and the growers seldom expect an abundant crop more than once in three years. The quantity of apples required to make a hogshead of cider is from twenty-four to thirty bushels; and in a good year an acre of orchard will produce somewhere about six hundred bushels, or from twenty to twenty-five hogsheads. The cider harvest is in September. When the season is favourable, the heaps of apples collected at the presses are immense—consisting of hundreds of tons. If any of the vessels used in the manufacture of cider are of lead, the beverage is not wholesome. The price of a hogshead of cider generally varies from 2l. to 5l., according to the season and quality; but cider of the finest growth has sometimes been sold as high as 20l. by the hogshead, direct from the press—a price equal to that of many of the fine wines of the Rhine or the Garonne."

Old Apple Trees"At Horton, in Buckinghamshire, where Milton spent some of his earlier years, there is an apple tree still growing, of which the oldest people remember to have heard it said that the poet was accustomed to sit under it. And upon the low leads of the church at Romsey, in Hampshire, there is an apple tree still bearing fruit, which is said to be two hundred years old."

The Fig and the Fine are equally interesting, and in connexion with the latter we notice the editor's mention of the fine vineyard at Arundel Castle. Aubrey describes a similar vineyard at Chart Park, near Dorking, another seat of the Howards. "Here was a vineyard, supposed to have been planted by the Hon. Charles Howard, who, it is said, erected his residence, as it were, in the vineyard." Again, "the vineyard flourished for some time, and tolerably good wine was made from the produce; but after the death of the noble planter, in 1713, it was much neglected, and nothing remained but the name. On taking down the house, a stone resembling a millstone, was found, by which the grapes were pressed."5 We were on the spot at the time, and saw the stone in question. Vines are still very abundant at Dorking, the soil being very congenial to their growth. "Hence, almost every house in this part has its vine; and some of the plants are very productive. The cottages of the labouring poor are not without this ornament, and the produce is usually sold by them to their wealthier neighbours, for the manufacture of wine. The price per bushel is from 4s. to 16s.; but the variableness of the season frequently disappoints them in the crops, the produce of which is sometimes laid up as a setoff to the rent."6

We have heard too of attempts in England to train the vine on the sides of hills, and a few years since an individual lost a considerable sum of money in making the experiment in the Isle of Wight.

At page 257, observes the editor,

A Vineyard"Associated as it is with all our ideas of beauty and plenty, is, in general, a disappointing object. The hop plantations of our own country are far more picturesque. In France, the vines are trained upon poles, seldom more than three or four feet in height; and 'the pole-clipt vineyard' of poetry is not the most inviting of real objects. In Spain, poles for supporting vines are not used; but cuttings are planted, which are not permitted to grow very high, but gradually form thick and stout stocks. In Switzerland, and in the German provinces, the vineyards are as formal as those of France. But in Italy is found the true vine of poetry, 'surrounding the stone cottage with its girdle, flinging its pliant and luxuriant branches over the rustic veranda, or twining its long garland from tree to tree.'7 It was the luxuriance and the beauty of her vines and her olives that tempted the rude people of the north to pour down upon her fertile fields:—

'The prostrate South to the destroyer yieldsHer boasted titles and her golden fields;With grim delight the brood of winter viewA brighter day, and heavens of azure hue.Scent the new fragrance of the breathing rose.And quaff the pendent vintage as it grows.'8"In Greece, too, as well as Italy, the shoots of the vines are either trained upon trees, or supported, so as to display all their luxuriance, upon a series of props. This was the custom of the ancient vine-growers; and their descendants have preserved it in all its picturesque originality.9 The vine-dressers of Persia train their vines to run up a wall, and curl over on the top. But the most luxurious cultivation of the vine in hot countries is where it covers the trellis-work which surrounds a well, inviting the owner and his family to gather beneath its shade. 'The fruitful bough by well' is of the highest antiquity."

Passing over the Mulberry, Currant, Gooseberry, and the Strawberry, the account of the Egg Plant is particularly attractive; and that of the Olive is well-written, but too long for extract.

Among the Tropical Fruits, the Orange and the Date are very delightful; and equal in importance and interest are the Cocoa Nut and Bread Fruit Tree. In short, it is impossible to open the volume without being gratified with the richness and variety of its contents, and the amiable feeling which pervades the inferences and incidental observations of the writer.

A word or two on the embellishments and we have done. These are far behind the literary merits of the volume, and are discreditable productions. Where so much is well done it were better to omit engravings altogether than adopt such as these: "they imitate nature so abominably." The group at page 223 is a fair specimen of the whole, than which nothing can be more lifeless. After the excellent cuts of Mr. London's Gardener's and Natural History Magazines, we turn away from these with pain, and it must be equally vexatious to the editor to see such accompaniments to his pages.

SHAKSPEARE'S BROOCH

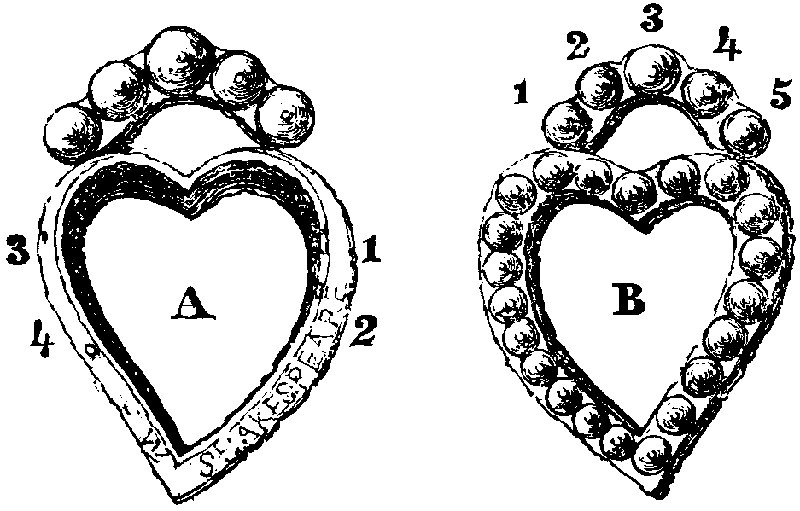

Having frequently observed in your valuable publication the great attention which you have paid to every thing relating to the "Immortal Bard of Avon," I beg leave to transmit to you two drawings (the one back, the other front) of a brooch or buckle, found near the residence of the poet, at New Place, Stratford, among the rubbish brought out from the spot where the house stood. This brooch is considered by the most competent judges and antiquarians in and near Stratford, to have been the personal property of Shakspeare. A. is the back; 1 and 2, faint traces of the letters which were nearly obliterated, by the person who found the relic, in scraping to ascertain whether the metal was precious, the whole of it being covered with gangrene or verdigris. 3 and 4 are the remains of the hinge to the pin. Fortunately the W. at the corner was preserved. B. represents the front of the brooch; 1, 3, and 5, are red stones in the top part (similar in shape to a coronet) 2 and 4 are blue stones in the same; the other stones in the bottom or heart are white, though varying rather in hue, and all are set in silver.

HJTHWC.N.B. The above is shown to the curious by the individual who found it—a poor man named Smith, living in Sheep Street, Stratford.

SPIRIT OF THE PUBLIC JOURNALS

The greater portion of the following Notes will, we are persuaded, be new to all but the bibliomaniacs in theatrical lore. They occur in a paper of 45 pages in the last Edinburgh Review, in which the writer attributes the Decline of the Drama to a variety of causes—as late hours, costly representations, high salaries, and excessive taxation—some of which we have selected for extract. In our affection for the Stage, we have paid some attention to its history, as well as to its recent state, and readily do we subscribe to a few of the Reviewer's opinions of the cause of its neglect. But to attribute this falling off to "taxes innumerable" is rather too broad: perhaps the highly-taxed wax lights around the box circles suggested this new light. We need not go so far to detect the rottenness of the dramatic state; still, as the question involves controversy at every point, we had rather keep out of the fight, and leave our Reviewer without further note or comment.

NOTES ON THE DRAMA

(From the Edinburgh Review, No. 98.)Origin of Admission MoneyThere were at Athens various funds, applicable to public purposes; one of which, and among the most considerable, was appropriated for the expensed of sacrifices, processions, festivals, spectacles, and of the theatres. The citizens were admitted to the theatres for some time gratis; but in consequence of the disturbances caused by multitudes crowding to get seats, to introduce order, and as the phrase is, to keep out improper persons, a small sum of money was afterwards demanded for admission. That the poorer classes, however, might not be deprived of their favourite gratification, they received from the treasury, out of this fund, the price of a seat—and thus peace and regularity were secured, and the fund still applied to its original purpose. The money that was taken at the doors, having served as a ticket, was expended, together with that which had not been used in this manner, to maintain the edifice itself, and to pay the manifold charges of the representation.

"Dramatic Representations natural to Man."Travellers inform us, that savages, even in a very rude state, are found to divert themselves by imitating some common event in life: but it is not necessary to leave our own quiet homes to satisfy ourselves, that dramatic representations are natural to man. All children delight in mimicking action; many of their amusements consist in such performances, and are in every sense plays. It is curious, indeed, to observe at how early an age the young of the most imitative animal, man, begin to copy the actions of others; how soon the infant displays its intimate conviction of the great truth, that "all the world's a Stage." The baby does not imitate those acts only, that are useful and necessary to be learned; but it instinctively mocks useless and unimportant actions and unmeaning sounds, for its amusement, and for the mere pleasure of imitation, and is evidently much delighted when it is successful. The diversions of children are very commonly dramatic. When they are not occupied with their hoops, tops, and balls, or engaged in some artificial game, they amuse themselves in playing at soldiers, in being at school, or at church, in going to market, in receiving company; and they imitate the various employments of life with so much fidelity, that the theatrical critic, who delights in chaste acting, will often find less to censure in his own little servants in the nursery, than in his majesty's servants in a theatre-royal. When they are somewhat older they dramatize the stories they read; most boys have represented Robin Hood, or one of his merry-men, and every one has enacted the part of Robinson Crusoe, and his man Friday. We have heard of many extraordinary tastes and antipathies; but we never knew an instance of a young person, who was not delighted the first time he visited a theatre. The true enjoyment of life consists in action; and happiness, according to the peripatetic definition, is to be found in energy; it accords, therefore, with the nature and etymology of the drama, which is, in truth, not less natural than agreeable. Its grand divisions correspond, moreover, with those of time; the contemplation of the present is Comedy—mirth for the most part being connected with the present only—and the past and the future are the dominions of the Tragic muse.

Grecian TheatresThe climate of Athens being one of the finest and most agreeable in the world, the Athenians passed the greatest part of their time in the open air; and their theatres, like those in the rest of Greece and in ancient Rome, had no other covering than the sky. Their structure accordingly differed greatly from that of a modern playhouse, and the representation in many respects was executed in a different manner. But we will mention those peculiarities only which are necessary to render our observations intelligible.

The ancient theatres, in the first place, were on a much larger scale than any that have been constructed in later days. It would have been impossible, by reason of the magnitude of the edifice, and consequently of the stage, to have changed the scenes in the same manner as in our smaller buildings. The scene, as it was called, was a permanent structure, and resembled the front of Somerset House, of the Horse Guards, or the Tuileries, and was in the same style of architecture as the rest of the spacious edifice. There were three large gateways, through each of which a view of streets, or of woods, or of whatever was suitable to the action represented, was displayed; this painting was fixed upon a triangular frame, that turned on an axis, like a swivel seal, or ring, so that any one of the three sides might be presented to the spectators, and perhaps the two that were turned away might be covered with other subjects, if it were necessary. If parts of Regent Street, or of Whitehall, or the Mansion House, and the Bank of England, were shown through the openings in the fixed scene, it would be plain that the fable was intended to be referred to London; and it would be removed to Edinburgh, or Paris, if the more striking portions of those cities were thus exhibited. The front of the scene was broken by columns, by bays and promontories in the line of the building, which gave beauty and variety to the façade, and aided the deception produced by the paintings that were seen through the three openings. In the Roman Theatres there were commonly two considerable projections, like large bow-windows, or bastions, in the spaces between the apertures; this very uneven line afforded assistance to the plot, in enabling different parties to be on the stage at the same time, without seeing one another. The whole front of the stage was called the scene, or covered building, to distinguish it from the rest of the theatre, which was open to the air, except that a covered portico frequently ran round the semicircular part of the edifice at the back of the highest row of seats, which answered to our galleries, and was occupied, like them, by the gods, who stood in crowds upon the level floor of their celestial abodes.

Immediately in front of the stage, as with us, was the orchestra; but it was of much larger dimensions, not only positively, but in proportion to the theatre. In our playhouses it is exclusively inhabited by fiddles and their fiddlers; the ancients appropriated it to more dignified purposes; for there stood the high altar of Bacchus, richly ornamented and elevated, and around it moved the sacred Chorus to solemn measures, in stately array and in magnificent vestments, with crowns and incense, chanting at intervals their songs, and occupied in their various rites, as we have before mentioned. It is one of the many instances of uninterrupted traditions, that this part of our theatres is still devoted to receive musicians, although, in comparison with their predecessors, they are of an ignoble and degenerate race.

The use of masks was another remarkable peculiarity of the ancient acting. It has been conjectured, that the tragic mask was invented to conceal the face of the actor, which, in a small city like Athens, must have been known to the greater part of the audience, as vulgar in expression, and it sometimes would have brought to mind most unseasonably the remembrance of a life and of habits, that would have repelled all sympathy with the character which he was to personate. It would not have been endured, that a player should perform the part of a monarch in his ordinary dress, nor that of a hero with his own mean physiognomy. It is probable, also, that the likeness of every hero of tragedy was handed down in statues, medals, and paintings, or even in a series of masks; and that the countenance of Theseus, or of Ajax, was as well known to the spectators as the face of any of their contemporaries. Whenever a living character was introduced by name, as Cleon or Socrates, in the old comedy, we may suppose that the mask was a striking, although not a flattering portrait. We cannot doubt, that these masks were made with great care, and were skilfully painted, and finished with the nicest accuracy; for every art was brought to a focus in the Greek theatres. We must not imagine, like schoolboys, that the tragedies of Sophocles were performed at Athens in such rude masks as are exhibited in our music shops. We have some representations of them in antique sculptures and paintings, with features somewhat distorted, but of exquisite and inimitable beauty.

The Roman StageThe Drama of ancient Rome possesses little of originality or interest. The word Histrio is said to be of Etruscan origin; the Tuscans, therefore, had their theatres; but little information can now be gleaned respecting them. It was long before theatres were firmly and permanently established in Rome; but the love of these diversions gradually became too powerful for the censors, and the Romans grew, at last, nearly as fond of them as the Greeks. The latter, as St. Augustine informs us, did not consider the profession of a player as dishonourable: "Ipsos scenicos non turpes judicaverunt, sed dignos etiam præclaris honoribus habuerunt."—De Civ. Dei. The more prudish Romans, however, were less tolerant; and we find in the Code various constitutions levelled against actors, and one law especially, which would not suit our senate, forbidding senators to marry actresses; but this was afterwards relaxed by Justinian, who had broken it himself. He permitted such marriages to take place on obtaining the consent of the emperor, and afterwards without, so that the lady quitted the stage, and changed her manner of life. The Romans, however, had at least enough of kindly feeling towards a Comedian to pray for the safety, or refection, of his soul after death; this is proved by a pleasant epitaph on a player, which is published in the collection of Gori:—

Pro jocis, quibus cunctosoblectabat,Si quid oblectamenti apudvos estManes, insontem reficiteAnimulam."CostumeIt is probable that the imagination of the spectator could without difficulty dispense with scenes, particularly if the surrounding objects were somewhat removed from the ordinary aspect of every-day things; if the performance were to take place, for example, in the hall of a college, or in a church.

The costume that prevails at present almost universally, is so barbarous and mean, and it changes in so many minute particulars so frequently, that it is impossible to conceive the hero of a tragedy actually wearing such attire. A more picturesque dress seems therefore to be indispensable; but the essentials of the costume of any time, from which dramatic subjects could be taken, are by no means costly. All that is absolutely necessary in vestments to content the fancy, might be procured at a trifling expense, and the hero or heroine might be supplied with the ordinary apparel of Greece, or Rome, or of any other country, at a small price. We must carefully distinguish, however, between the necessaries and the luxuries of deception; the form, and sometimes the colour, demand a scrupulous accuracy; the texture is always unimportant. We may comprehend, therefore, how the old English theatre, notwithstanding the small outlay on decorations, by a strict attention to essentials, possessed considerable attractions; we may readily believe, that there were many companies who were maintained by their trade; "that all those companies got money and lived in reputation, especially those of the Blackfriars, who were men of grave and sober behaviour."

The Old DramaOur literature is remarkably rich in old dramas; but they are of little use to the present age. Fastidiousness and hypocrisy have grown for many years, slowly but surely, and have at last arrived at such a pitch, that there is hardly a line in the works of our old comic writers, which is not reprobated as immoral, or at least vulgar. The excessive squeamishness of taste of the present day is very unfavourable to the genius of comedy, which demands a certain liberty and a freedom from restraints. This morbid delicacy is a great evil, for it renders the time of limitation in all comic writings exceedingly short. The ephemeral duration of the fashion, which is all the production of a man of wit can now enjoy, discourages authors. There is no motive to bestow much care on such compositions, and they fall below the ambition of men of real talents—for the best part of the reward of literary labour consists in the lasting admiration of posterity; and as some new fastidiousness will consign to oblivion, in a short time, every comic production, it is plain that such a reward cannot be reasonably anticipated. We are more completely, than any other nation, the victims of fashion. Everything here must either be in the last and newest fashion, or it must cease to be. The despotism of fashion in dress, in furniture, and in the pattern of the edges of plate, is perhaps inconvenient—it is, however, not very important; but it is a cruel grievance that it should interfere with and annihilate an entire department of our literature.

Hours of RepresentationDramatic representations were formerly given, not only in Greece and Rome, but in England also, in the daytime, and in the open air. "The Globe, Fortune, and Bull, were large houses, and partly open to the weather, and there they always acted by daylight;" and plays were first acted in Spain in the open courts of great houses, which were sometimes covered, in whole or in part, with an awning to keep off the sun. The word sale, which is used as a stage direction, meaning not exit, but he enters, i.e. he comes out of the house into the open air, is an evidence of the old practice. We are inclined to think that the morning is more favourable to dramatic excellence than the evening. The daylight accords with the truth and sobriety of nature, and it is the season of cool judgment: the gilded, the painted, the tawdry, the meretricious—spangles and tinsel, and tarnished and glittering trumpery—demand the glare of candle-light and the shades of night. It is certain, that the best pieces were written for the day; and it is probable, that the best actors were those who performed whilst the sun was above the horizon. The childish trash which now occupies so large a portion of the public attention could not, it is evident, keep possession of the stage, if it were to be presented, not at ten o'clock at night, but twelve hours earlier. Much would need to be changed in the dresses, scenery, and decorations, and in many other respects, in the pieces, the solid merits of which would be able to undergo the severe ordeal; and if we consider what changes would be required to adapt them to the altered hours, we shall find that they will be all in favour of good taste, and on the side of nature and simplicity. The day is a holy thing; Homer aptly calls it [Greek: ieron aemar]ιερον ημαρ, and it still retains something of the sacred simplicity of ancient times. It is, at all events, less sophisticated and polluted than the modern night, a period which is not devoted to wholesome sleep, but to various constraints and sufferings, called, in bitter mockery, Pleasure. The late evening, being a modern invention, is therefore devoted to fashion; to recur to the simple and pure in theatricals, it would probably be necessary to effect an escape from a period of time, which has never been employed in the full integrity of tasteful elegance; and thus to break the spell, by which the whole realm of fancy has long been bewitched. An absurd and inconvenient practice, which is almost peculiar to this country, of attending public places in that uncomfortable condition, which is technically called being dressed, but which is in truth, especially in females, being more or less naked and undressed, might more easily be dispensed with by day, and on that account, and for many other reasons, it would be less difficult to return home.