полная версия

полная версияThe Mirror Of Literature, Amusement, And Instruction. Volume 14, No. 391, September 26, 1829

Various

The Mirror Of Literature, Amusement, And Instruction / Volume 14, No. 391, September 26, 1829

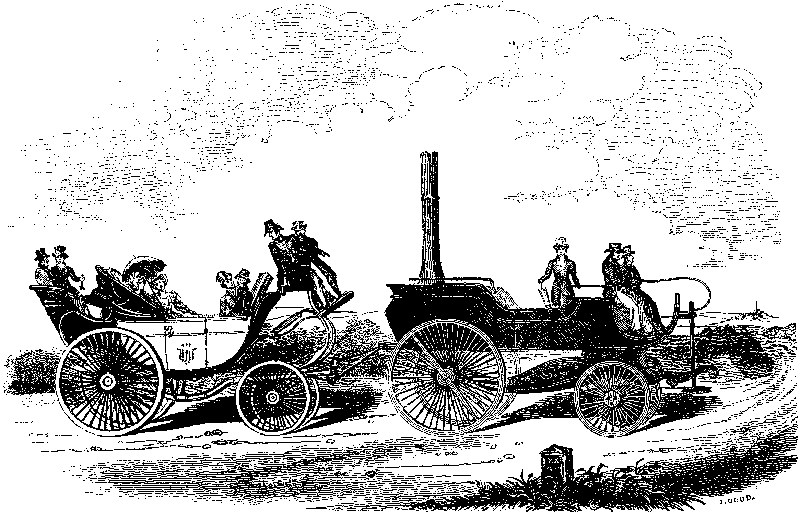

GURNEY'S IMPROVED STEAM CARRIAGE.

MR. GURNEY'S IMPROVED STEAM CARRIAGE

Mr. Gurney, in perfecting this invention, has followed Dr. Franklin's advice—to tire and begin again. It is now four years since he first commenced his ingenious enterprise; and nearly two years since we reported and illustrated the progress he had made. (See MIRROR, vol. x. page 393, or No. 287.) He began with a large boiler, but public prejudice was too strong for it; and knowing people talked of high pressure accidents; the steam, could not, of course, be altogether got rid of, so to divide the danger, Mr. Gurney made his boiler in forty welded iron pipes; still the steam ran in a main pipe beneath the whole of the carriage, and the evil was but modified. At length the inventer has detached the engine and boiler, or locomotive part of the apparatus, which is now to be fastened to the carriage, and may be considered as a STEAM-HORSE, with no more danger than we should apprehend from a restive animal, in whose veins the steam or mettle circulates with too high a pressure. Fair trials have been made of the Improved Carriage on our common roads, the Premier has decided the machine "to be of great national importance," from sundry experiments witnessed by his grace, at Hounslow Barracks; and the coach is announced "really to start next month (the 1st) in working—not experimental journeys—for travellers between London and Bath."1 Crack upon crack will follow joke upon joke; the Omnibus, with its phaeton-like coursers will be eclipsed; and a journey to Bath and the Hot Wells by steam will soon be an everyday event.

Descriptions of Mr. Gurney's carriage have been so often before the public, that extended detail is unnecessary. Besides, all our liege subscribers will turn to the account in our No. 287. The recent improvements have been perspicuously stated by Mr. Herapath, of Cranford, in a letter in the Times newspaper, and we cannot do better than adopt and abridge a portion of his communication.

"The present differs from the earlier carriage, in several improvements in the machinery, suggested by experiment; also in having no propellers;2 and in having only four wheels instead of six; the apparatus for guiding being applied immediately to the two fore-wheels, bearing a part of the weight, instead of two extra leading wheels bearing little or none. No person can conceive the absolute control this apparatus gives to the director of the carriage, unless he has had the same opportunities of observing it which I had in a ride with Mr. Gurney. Whilst the wheels obey the slightest motions of the hand, a trifling pressure of the foot keeps them inflexibly steady, however rough the ground. To the hind axle, which is very strong, and bent into two cranks of nine inches radius, at right angles to each other, is applied the propelling power by means of pistons from two horizontal cylinders. By this contrivance, and a peculiar mode of admitting the steam to the cylinders, Mr. Gurney has very ingeniously avoided that cumbersome appendage to steam-engines, the fly-wheel, and preserves uniformity of action by constantly having one cylinder on full pressure, whilst the other is on the reduced expansive. The dead points—that is, those in which a piston has no effect from being in the same right line with its crank,—are also cleared by the same means. For as the cranks are at right angles, when one piston is at a dead point, the other has a position of maximum effect, and is then urged by full steam power; but no sooner has the former passed the dead point, than an expansion valve opens on it with full steam, and closes on the latter. Firmly fixed to the extremities of the axle, and at right angles to it, are the two 'carriers'—(two strong irons extending each way to the felloes of the wheels.) These irons may be bolted to the felloes of the wheels or not, or to the felloes of one wheel only. Thus the power applied to the axle is carried at once to the parts of the wheels of least stress—the circumferences. By this artifice the wheels are required to be of no greater strength and weight than ordinary carriage-wheels; and, like them, they turn freely and independently on the axle; but one or both may be secured as part and parcel of the axle, as circumstances require. The carriage is consequently propelled by the friction or hold which either or both hind-wheels, according as the power is applied to them jointly or separately, have on the ground. Beneath the hind part drop two irons, with flat feet, called 'shoe-drags.' A well-contrived apparatus, with a spindle passing up through a hollow cylinder, to which the guiding handle is affixed, enables the director to force one or both drags tight on the road, so as to retard the progress in a descent, or if he please, to raise the wheels off the ground. The propulsive power of the wheels being by this means destroyed, the carriage is arrested in a yard or two, though going at the rate of eighteen or twenty miles an hour. On the right hand of the director lies the handle of the throttle-valve, by which he has the power of increasing or diminishing the supply of steam ad libitum, and hence of retarding or accelerating the carriage's velocity. The whole carriage and machinery weigh about 16 cwt., and with the full complement of water and coke 20 or 22 cwt., of which, I am informed, about 16 cwt. lie on the hind-wheels."

Mr. H. then enumerates the principle of the improvements:—"That troublesome appendage the fly-wheel, as I have observed, Mr. Gurney has rendered unnecessary. The danger to be apprehended in going over rough pitching, from too rapid a generation of steam, he avoids by a curious application of springs; and should these be insufficient, one or two safety valves afford the ultimatum of security. He ensures an easy descent down the steepest declivity by his 'shoe-drags,' and the power of reversing the action of the engines. His hands direct, and his foot literally pinches obedience to the course over the roughest and most refractory ground. The dreadful consequences of boiler-bursting are annihilated by a judicious application of tubular boilers. Should, indeed, a tube burst, a hiss about equal to that of a hot nail plunged into water, contains the sum total of alarm, while a few strokes with a hammer will set all to rights again. Lastly, he has so contrived his 'carriers,' that they shall act without confining the wheels, by which means there is none of that sliding and consequent cutting up of the road, which, in sharp turnings, would result from inflexible constraint.

"Hills and loose, slippery ground are well known to be the res adversæ of steam-carriages; on ordinary level roads they roll along with rapid facility. In every ascent there are two additional circumstances inimical to progressive motion. One is, that carriages press less on the ground of a hill than on that of a plain, thus giving the wheels a less forcible grasp or bite. But this may be easily remedied in the structure of a carriage, and is not of very material consequence in the steepest hills that we have. The other is more serious. When a carriage ascends a hill, the weight or gravity of the whole is decomposable into two—one perpendicular, and the other parallel to the road. The former constitutes the pressure on the road, the latter the additional work the engine has to perform. Universally this is the same part of the whole carriage and its load together, which the perpendicular ascent of the hill is of its length. With these principles, if we knew the bite of the wheels on the road, we could at once subject the powers of Mr. Gurney's carriage to calculation.

"Now, from one of the experiments made in the barrack-yard, at Hounslow, I find we can approximate towards it. For instance, with one wheel only fixed to the 'carriers,' the carriage drew itself and load of water and coke (about 1 ton), with three men on it, and a wagon behind of 16 cwt. containing 27 soldiers. This, at the rate of 1-1/2 cwt. to a man, in round numbers is 4 tons. Estimating the force of traction of spring carriages at a twelfth of the total weight, it consequently gives a hold or bite on the road of 1-12 of 4 tons, or 6 2-3rds cwt. per wheel, or 13 1-3rd cwt. for the two wheels. This is likewise the propelling force of the carriage. Supposing, therefore, we were ascending a hill of 1 foot rise in 8, which I am assured exceeds in steepness any hill we have, we should be able to draw a load behind of 2 tons 2 cwt., or between 3 and 4 tons altogether....

"On a good level road I think it not improbable it might draw, instead of 7 tons which our experiment would give, from 10 to 11, besides its own weight, or 100 ordinary men, exclusive of 2 or 3 tons for carriages; and up one of our steepest hills, 3 tons besides itself, or 25 men besides a ton for a carriage. This it would do at a rate of 8, 9, or 10 miles an hour. For it is a singular feature in this carriage, and which was remarked by many at the time, that it maintained very nearly the same speed with a wagon and 27 men, that it did with the carriage and only 5 or 6 persons. But there is a fact connected with this machine still more extraordinary. For instance, every additional cwt. we shift on the hind or working wheels, will increase the power of traction in our steepest hills upwards of 4 cwt., and on the level road half a ton. Such, then, is the paradoxical nature of steam-carriages, that the very circumstance which in animal exertion would weaken and retard, will here multiply their strength and accelerate. This, no doubt, Mr. Gurney's ingenuity will soon turn to profitable account.

"It has often been asserted that carriages of this sort could not go above 6 or 7 miles an hour. I can see no reasonable objection to 20. The following fact, decided before a large company in the barrack-yard, will best speak for itself:—At eighteen minutes after three I ascended the carriage with Mr. Gurney. After we had gone about half way round, 'Now,' said Mr. Gurney, 'I will show you her speed.' He did, and we completed seven turns round the outside of the road by twenty-eight minutes after three. If, therefore, as I was there assured, two and a half turns measured one mile, we went 2.8 miles in ten minutes; that is, at the rate of 16.8, or nearly 17 miles per hour. But as Mr. Gurney slackened its motion once or twice in the course of trial, to speak to some one, and did not go at an equal rate all the way round for fear of accident in the crowd, it is clear that sometimes we must have proceeded at the rate of upwards of twenty miles an hour."

The Engraving will furnish the reader with a correct idea of such of Mr. Gurney's improvements as are most interesting to the public. The present arrangement is certainly very preferable to placing the boiler and engine in immediate contact with the carriage, which is to convey goods and passengers. Men of science are still much divided on the practical economy of using steam instead of horses as a travelling agent; but we hope, like all great contemporaries they may whet and cultivate each other till the desired object is attained. One of them, a writer in the Atlas, observes, that "if ultimately found capable of being brought into public use, it would probably be most convenient and desirable that several locomotive engines should be employed on one line of road, in order that they might be exchanged at certain stages for the purposes of examination, tightening of screws, and other adjustments, which the jolting on passing over the road might render necessary, and for the supply of fuel and water."

An effectively-coloured lithographic of Mr. Gurney's carriage (by Shoesmith) has recently appeared at the printsellers', which we take this opportunity of recommending to the notice of collectors and scrappers.

PUNNING SATIRE ON AN INCONSTANT LOVER

You are as faithless as a Carthaginian,To love at once, Kate, Nell, Doll, Martha, Jenny, Anne.SWIFT.BRIMHAM ROCKS 3 BY MOONLIGHT

(For the Mirror.)The sun hath set, but yet I linger still,Gazing with rapture on the face of night;And mountain wild, deep vale, and heathy hill,Lay like a lovely vision, mellow, bright,Bathed in the glory of the sunset light,Whose changing hues in flick'ring radiance play,Faint and yet fainter on the outstretch'd sight,Until at length they wane and die away,And all th' horizon round fades into twilight gray.But, slowly rising up the vaulted sky,Forth comes the moon, night's joyous, sylvan queen,With one lone, silent star, attendant byHer side, all sparkling in its glorious sheen;And, floating swan-like, stately, and serene,A few light fleecy clouds, the drapery of heav'n,Throw their pale shadows o'er this witching scene,Deep'ning its mystic grandeur—and seem drivenRound these all shapeless piles like Time's wan spectres risenFrom out the tombs of ages. All aroundLies hushed and still, save with large, dusky wingThe bird of night makes its ill-omened sound;Or moor-game, nestling 'neath th' flowery lingLow chuckle to their mates—or startled, springAway on rustling pinions to the sky,Wheel round and round in many an airy ring,Then swooping downward to their covert hie,And, lodged beneath the heath again securely lie.Ascend yon hoary rock's impending brow,And on its windy summit take your stand—Lo! Wilsill's lovely vale extends below,And long, long heathy moors on either handStretch dark and misty—a bleak tract of land,Whereon but seldom human footsteps come;Save when with dog, obedient at command,And gun, the sportsman quits his city home,And brushing through the ling in quest of game doth roam.And lo! in wild confusion scattered round,Huge, shapeless, naked, massy piles of stoneRise, proudly towering o'er this barren ground,Scowling in mutual hate—apart, alone,Stern, desolate they stand—and seeming thrownBy some dire, dread convulsion of the earthFrom her deep, silent caves, and hoary grownWith age and storms that Boreas issues forthReplete with ire from his wild regions in the north.How beautiful! yet wildly beautiful,As group on group comes glim'ring on the eye,Making the heart, soul, mind, and spirit fullOf holy rapture and sweet imagery;Till o'er the lip escapes th' unconscious sigh,And heaves the breast with feeling, too too deepFor words t' express the awful sympathy,That like a dream doth o'er the senses creep,Chaining the gazer's eye—and yet he cannot weep.But stands entranced and rooted to the spot,While grows the scene upon him vast, sublime,Like some gigantic city's ruin, notInhabited by men, but Titans—TimeHere rests upon his scythe and fears to climb,Spent by th' unceasing toil of ages past,Musing he stands and listens to the chimeOf rock-born spirits howling in the blast,While gloomily around night's sable shades are cast.Well deemed I ween the Druid sage of oldIn making this his dwelling place on high;Where all that's huge and great from Nature's mould,Spoke this the temple of his deity;Whose walls and roof were the o'erhanging sky,His altar th' unhewn rock, all bleak and bare,Where superstition with red, phrensied eyeAnd look all wild, poured forth her idol prayer,As rose the dying wail,4 and blazed the pile in air.Lost in the lapse of time, the Druid's loreHath ceased to echo these rude rocks among;No altar new is stained with human gore;No hoary bard now weaves the mystic song;Nor thrust in wicker hurdles, throng on throng,Whole multitudes are offered to appeaseSome angry god, whose will and power of wrongVainly they thus essayed to soothe and please—Alas! that thoughts so gross man's noblest powers should seize.But, bowed beneath the cross, see! prostrate fallThe mummeries that long enthralled our isle;So perish error! and wide over allLet reason, truth, religion ever smile:And let not man, vain, impious man defileThe spark heaven lighted in the human breast;Let no enthusiastic rage, no sophist's wileLull the poor victim into careless rest,Since the pure gospel page can teach him to be blest.Weak, trifling man, O! come and ponder hereUpon the nothingness of human things—How vain, how very vain doth then appearThe city's hum, the pomp and pride of kings;All that from wealth, power, grandeur, beauty springs,Alike must fade, die, perish, be forgot;E'en he whose feeble hand now strikes the stringsSoon, soon within the silent grave must rot—Yet Nature's still the same, though we see, we hear her not.J. HORNER.Wilsill, near Pateley Bridge, Sept. 1829.

MANNERS & CUSTOMS OF ALL NATIONS

PLEDGING HEALTHS

The origin of the very common expression, to pledge one drinking, is curious: it is thus related by a very celebrated antiquarian of the fifteenth century. "When the Danes bore sway in this land, if a native did drink, they would sometimes stab him with a dagger or knife; hereupon people would not drink in company unless some one present would be their pledge or surety, that they should receive no hurt, whilst they were in their draught; hence that usual phrase, I'll pledge you, or be a pledge for you." Others affirm the true sense of the word was, that if the party drank to, were not disposed to drink himself, he would put another for a pledge to do it for him, else the party who began would take it ill.

J.W.RUSSIAN SUPERSTITION

The extreme superstition of the Greek church, the national one of Russia, seems to exceed that of the Roman Catholic devotees, even in Spain and Portugal. The following instance will show the absurdity of it even among the higher classes:—

A Russian princess, some few years since, had always a large silver crucifix following her in a separate carriage, and which was placed in her chamber. When any thing fortunate happened to her in the course of the day, and she was satisfied with all that had occurred, she had lighted tapers placed around the crucifix, and said to it in a familiar style, "See, now, as you have been very good to me to-day, you shall be treated well; you shall have candles all night; I will love you; I will pray to you." If on the contrary, any thing happened to vex the lady, she had the candles put out, ordered her servants not to pay any homage to the poor image, and loaded it herself with the bitterest reproaches.

INA.THE SELECTOR; AND LITERARY NOTICES OF NEW WORKS

LIBRARY OF ENTERTAINING KNOWLEDGE

FruitsThis Part (5) completes the volume of "Vegetable Substances used in the Arts and in Domestic Economy." The first portion—Timber Trees was noticed at some length in our last volume (page 309,) and received our almost unqualified commendation, which we are induced to extend to the Part now before us. Still, we do not recollect to have pointed out to our readers that which appears to us the great recommendatory feature of this series of works—we mean the arrangement of the volumes—their subdivisions and exemplifications—and these evince a master-hand in compilation.

Every general reader must be aware that little novelty could be expected in a brief History and Description of Timber Trees and Fruits, and that the object of the Useful Knowledge Society was not merely to furnish the public with new views, but to present in the most attractive form the most entertaining facts of established writers, and illustrate their views with the observations of contemporary authors as well as their own personal acquaintance with the subjects. In this manner, the Editor has taken "a general and rapid view of fruits," and, considering the great hold their description possesses on all readers, we are disposed to think almost too rapid. We should have enjoyed a volume or two more than half a volume of such reading as the present; but as we are not purchasers, and are unacquainted with the number to which the Society propose to extend their works, we ought not perhaps to raise this objection, which, to say the truth, is a sort of negative commendation. Hitherto, we have been accustomed to see compilations of pretensions similar to the present, executed with little regard to neatness or unity, or weight or consideration. Whole pages and long extracts have been stripped and sliced off books, with little rule or arrangement, and what is still worse, without any acknowledgment of the sources. The last defect is certainly the greatest, since, in spite of ill-arrangement, an intelligent inquirer may with much trouble, avail himself of further reference to the authors quoted, and thus complete in his own mind what the compiler had so indifferently begun. The work before us is, however, altogether of a much higher order than general compilations. The introductions and inferences are pointed and judicious, and the facts themselves of the most interesting character, are narrated in a condensed but perspicuous style; while the slightest reference will prove that the best and latest authorities have been appreciated. Thus, in the History and Description of Fruits, the Transactions of the Horticultural Society are frequently and pertinently quoted to establish disputed points, as well as the journals of intelligent travellers and naturalists; with occasional poetical embellishments, which lend a charm even to this attractive species of reading.

To quote the history of either Fruit entire, would not so well denote the character of the work as would a few of the most striking passages in the descriptions. In the introductory chapter we are pleased with the following passage on Monastic Gardens.

"The monks, after the conversion of the Anglo-Saxons to Christianity, appear to have been the only gardeners. As early as 674, we have a record, describing a pleasant and fruit-bearing close at Ely, then cultivated by Brithnoth, the first Abbot of that place. The ecclesiastics subsequently carried their cultivation of fruits as tar as was compatible with the nature of the climate, and the horticultural knowledge of the middle ages. Whoever has seen an old abbey, where for generations destruction only has been at work, must have almost invariably found it situated in one of the choicest spots, both as to soil and aspect; and if the hand of injudicious improvement has not swept it away, there is still the 'Abbey-garden.' Even though it has been wholly neglected—though its walls be in ruins, covered with stone-crop and wall-flower, and its area produce but the rankest weeds—there are still the remains of the aged fruit trees—the venerable pears, the delicate little apples, and the luscious black cherries. The chestnuts and the walnuts may have yielded to the axe, and the fig trees and vines died away;—but sometimes the mulberry is left, and the strawberry and the raspberry struggle among the ruins. There is a moral lesson in these memorials of the monastic ages. The monks, with all their faults, were generally men of peace and study; and these monuments show that they were improving the world, while the warriors were spending their lives to spoil it. In many parts of Italy and France, which had lain in desolation and ruin from the time of the Goths, the monks restored the whole surface to fertility; and in Scotland and Ireland there probably would not have been a fruit tree till the sixteenth century, if it had not been for their peaceful labours. It is generally supposed that the monastic orchards were in their greatest perfection from the twelfth to the fifteenth century."

Again, the

Naturalization of Plants"The large number of our native plants (for we call those native which have adapted themselves to our climate) mark the gradual progress of our civilization through the long period of two thousand years; whilst the almost infinite diversity of exotics which a botanical garden offers, attest the triumphs of that industry which has carried us as merchants or as colonists over every region of the earth, and has brought from every region whatever can administer to our comforts and our luxuries,—to the tastes and the needful desires of the humblest as well as the highest amongst us. To the same commerce we owe the potato and the pine-apple; the China rose, whose flowers cluster round the cottage-porch, and the Camellia which blooms in the conservatory. The addition even of a flower, or an ornamental shrub, to those which we already possess, is not to be regarded as a matter below the care of industry and science. The more we extend our acquaintance with the productions of nature, the more are our minds elevated by contemplating the variety, as well as the exceeding beauty, of the works of the Creator. The highest understanding does not stoop when occupied in observing the brilliant colour of a blossom, or the graceful form of a leaf. Hogarth, the great moral painter, a man in all respects of real and original genius, writes thus to his friend Ellis, a distinguished traveller and naturalist:—'As for your pretty little seed-cups, or vases, they are a sweet confirmation of the pleasure Nature seems to take in superadding an elegance of form to most of her works, wherever you find them. How poor and bungling are all the imitations of Art! When I have the pleasure of seeing you next, we will sit down, nay, kneel down if you will, and admire these things.'