полная версия

полная версияThe Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 19, No. 539, March 24, 1832

QUEEN.

Didst ever look upon the dead?GONZALES.

Ay, madam,Full oft; and in each calm or frightful guiseDeath comes in,—on the bloody battle-field;When with each gush of black and curdling lifeA curse was uttered,—when the pray'rs I've pour'd,Have been all drown'd with din of clashing arms—And shrieks and shouts, and loud artillery,That shook the slipp'ry earth, all drunk with gore—I've seen it, swoll'n with subtle poison, blackAnd staring with concentrate agony—When ev'ry vein hath started from its bed,And wreath'd like knotted snakes, around the browsThat, frantic, dash'd themselves in tortures downUpon the earth. I've seen life float awayOn the faint sound of a far tolling bell—Leaving its late warm tenement as fair,As though 'twere th' incorruptible that layBefore me—and all earthly taint had vanish'dWith the departed spirit.Laval returns from Italy to claim his bride. In the earlier part of the play, a hint is given of Gonzales' rancorous hate of Laval, the undercurrent of which is now revealed. Gonzales, beneath the seal of confession, obtains the secret of the crime of Françoise. In her presence, as the betrothed Laval rushes to embrace his bride, he taunts him with her guilt. The wretched Françoise, in vain conjured to assert her innocence, stabs herself. The King had been followed thither by the Queen; both now appear. Gonzales riots revenge in one of the most vigorous portions of the drama:

GONZALES.

Look on thy bride! look on that faded thing,That e'en the tears thy manhood showers go fast,And bravely, cannot wake to life again!I call all nature to bear witness here—As fair a flower once grew within my home,As young, as lovely, and as dearly lov'd—I had a sister once, a gentle maid—The only daughter of my father's house,Round whom our ruder loves did all entwine,As round the dearest treasure that we own'd.She was the centre of our souls' affections—She was the bud, that underneath our strongAnd sheltering arms, spread over her, did blow.So grew this fair, fair girl, till envious fateBrought on the hour when she was withered.Thy father, sir—now mark—for 'tis the pointAnd moral of my tale—thy father, then,Was, by my sire, in war ta'en prisoner—Wounded almost to death, he brought him home,Shelter'd him,—cherish'd him,—and, with a care,Most like a brother's, watch'd his bed of sickness,Till ruddy health, once more through all his veinsSent life's warm stream in strong returning tide.How think ye he repaid my father's love?From her dear home he lur'd my sister forth,And, having robb'd her of her treasur'd honour,Cast her away, defil'd,—despoil'd—forsaken—The daughter of a high and ancient line—The child of so much love—she died—she died—Upon the threshold of that home, from whichMy father spurn'd her—over whose pale corseI swore to hunt, through life, her ravisher—Nor ever from by bloodhound track desist,Till line and deep atonement had been made—Honour for honour given—blood for blood."The Queen orders Gonzales to death; but the monk accuses her of the intended murder of Françoise, and produces her written order to that effect. The King can no longer be blind to his mother's crimes; she is disgraced, degraded, and condemned to pass the rest of her days in a convent."

Here the fourth act, and the acting play closes. In the fifth De Bourbon reappears. Lautrec proposes to join him, and assassinate the King, in revenge for the ruin of Françoise. The memorable battle of Pavia ensues, and terminates with the death of the King and the triumph of Bourbon.

Triboulet, the jester of the Court of Francis, is introduced with some pleasantry, by way of relief to the darker deeds.

We cannot conclude this imperfect sketch better than by the following judicious observations from the Quarterly Review: "How high Miss Kemble's young aspirings have been—what conceptions she has formed to herself of the dignity of tragic poetry—may be discovered from this most remarkable work; at this height she must maintain herself, or soar a still bolder flight. The turmoil, the hurry, the business, the toil, even the celebrity of a theatric life must yield her up at times to that repose, that undistracted retirement within her own mind, which, however brief, is essential to the perfection of the noblest work of the imagination—genuine tragedy. Amidst her highest successes on the stage, she must remember that the world regards her as one to whom a still higher part is fallen. She must not be content with the fame of the most extraordinary work which has ever been produced by a female at her age, (for as such we scruple not to describe her Francis the First,)—with having sprung at once to the foremost rank, not only of living actors but of modern dramatists;—she must consider that she has given us a pledge and earnest for a long and brightening course of distinction, in the devotion of all but unrivalled talents in two distinct, though congenial, capacities, to the revival of the waning glories of the English theatre."

SPIRIT OF THE PUBLIC JOURNALS

OLD ENGLISH MUSIC

It was in the course of the sixteenth century that the psalmody of England, and the other Protestant countries, was brought to the state in which it now remains, and in which it is desirable that it should continue to remain. For this psalmody we are indebted to the Reformers of Germany, especially Luther, who was himself an enthusiastic lover of music, and is believed to have composed some of the finest tunes, particularly the Hundredth Psalm, and the hymn on the Last Judgment, which Braham sings with such tremendous power at our great performances of sacred music. Our psalm-tunes, consisting of prolonged and simple sounds, are admirably adapted for being sung by great congregations; and as the effect of this kind of music is much increased by its venerable antiquity, it would be very unfortunate should it yield to the influence of innovation: for this reason, it is much to be desired that organists and directors of choirs should confine themselves to the established old tunes, instead of displacing them by modern compositions.

Towards the end of the sixteenth, and beginning of the seventeenth, century, shone that constellation of English musicians, whose inimitable madrigals are still, and long will be, the delight of every lover of vocal harmony. It is to Italy, however, that we are indebted for this species of composition. The madrigal is a piece of vocal music adapted to words of an amorous or cheerful cast, composed for four, five, or six voices, and intended for performance in convivial parties or private musical societies. It is full of ingenious and elaborate contrivances; but, in the happier specimens, contains likewise agreeable and expressive melody. At the period of which we now speak, vocal harmony was so generally cultivated, that, in social parties, the madrigal books were generally laid on the table, and every one was expected to take the part allotted to him. Any person who made the avowal of not being able to sing a part at sight was looked upon as unacquainted with the usages of good society—like a gentleman who now-a-days says he cannot play a game at whist, or a lady that she cannot join in a quadrille or a mazurka. The Italian madrigals of Luca Marenzio and others are still in request: and among the English madrigalists we may mention Wilbye, author of "Flora gave me fairest flowers;" Morley, whose "Now is the month of Maying" is so modern in its air, that it is introduced as the finale of one of our most popular operas, the Duenna; and Michael Este, the composer of the beautiful trio, "How merrily we live that Shepherds be." This music retains all its original freshness, and has been listened to, age after age, with unabated pleasure.

The glee, which is a simpler and less elaborate form of the madrigal,—and that amusing jeu d'esprit so well known by the name of Catch, made their appearance about the end of the sixteenth century. The first collection of catches that made its appearance in England is dated in 1609.—Metropolitan.

BENEDICTION ON CHILDREN

IMPROMPTUBy Thomas Campbell, EsqImps, that hold your daily revelsRound the windows of my bowerWould that Hell's ten thousand devilsHad you in their clutch this hour!Screaming, yelling, little nasties,Would that Ogres down their mawHad you cramm'd in Christmas pasties,That would make ye hold your jaw.Saucy imps, stew'd down to jelly,Ye would make a sauce most rare;Or with pudding in each belly,Rival roasted pig or hare.Sweeter than the fish of these is,Would be yours, young human bores;All with apples at your noses,Would I saw you dish'd by scores!Herod slaughter'd harmless sucklings,Not with tongues like yours to vex;Were he here, ye Devil's ducklings,I would bid him wring your necks.Metropolitan.

DRAMATIC CHARACTER OF THE CATHOLIC RELIGION

The religion of the south of Europe is still essentially dramatic; and it may be questioned how far this adaptation to the genius of the people has tended to perpetuate the influence, not only of the Roman Catholic, but also of the Greek church. Even in the pulpit, not merely does the earnest preacher, by vehement gesticulation, by the utmost variety of pause and intonation, act, as far as possible, the scenes which he describes; but the crucifix, if the expression may be permitted, plays the principal part; the Saviour is held forth to the multitude in the living and visible emblem of his sufferings. The ceremonies of the Holy Week in Rome are a most solemn, and to most minds, affecting religious drama. The oratorios, as with us, are in general on scriptural subjects; and operas on themes of equal sanctity are listened to without the least feeling of profanation. Nor are the more audacious exhibitions of the dark ages by any means exploded. Every traveller on the continent who has much curiosity, must have witnessed, whether with devout indignation or mere astonishment, the strange manner in which scriptural subjects are still represented by marionnettes, by tableax parlans, or even performed by regular actors. In the unphilosophized parts of modern Europe, these scenes are witnessed by the populace, not merely with respect, but with profound interest; and if they tend to perpetuate superstition, must be acknowledged likewise to keep alive religious sentiment. But if this be the case in the nineteenth century, how powerfully must such exhibitions have operated on the general mind in the dark ages! The alternative lay between total ignorance and this mode of communicating the truth. For the general mass of the clergy were then as ignorant as the laity; and as the wild work, which in these sacred dramas is sometimes made of the scripture history, may be supposed to have embodied the knowledge of a whole fraternity, we may not unfairly conjecture the kind of instruction to be obtained from each individual. The state of language in Europe must have greatly contributed to the adoption of public instruction, by means of dramatic representation. The services of the church were in Latin, now become a dead language. This originated, perhaps, rather in sincere reverence, and the dread of profaning the sacred mysteries by transferring them into the vulgar tongue, than in any systematic design of keeping the people in the dark; for, from the gradual extinction of the Latin, as the vernacular idiom, and the gradual growth of the modern languages, there was no marked period in which the change might appear to be called for, until the question became involved with weightier matters of controversy. The confusion of tongues, almost throughout Europe, before the great predominant languages were formed out of the conflicting dialects, must greatly have impeded the preaching the Gospel, for which, in other respects, only a very small part of the clergy were qualified. Though, in these times, most extraordinary effects are attributed to the eloquence of certain preachers, for instance, Fra. Giovanni di Vicenza, yet many of the itinerant friars, the first, we believe, who addressed the people with great activity in the vulgar tongue, must have been much circumscribed by the limits of their own patois. 5 But the spectacle of the dramatic exhibitions everywhere spoke a common language; and the dialogue, which, in parts of the Chester mysteries, is a kind of Anglicized French, and which, even if translated into the native tongue, was constantly interspersed with Latin, and therefore, but darkly and imperfectly understood, was greatly assisted by the perpetual interpretation which was presented before the eyes. The vulgar were thus imperceptibly wrought up to profound feelings of reverence for the purity of the Virgin; the unexampled sufferings of the Redeemer; the miraculous powers of the apostles, and the constancy of the martyrs; we must add, (for after all it was a strange Christianity, though in every respect the Christianity of the age,) with the most savage detestation at the cruelty of Herod or Pilate, and the treachery of Judas; and the most revolting horror, at the hideous appearance, and blasphemous language of the Prince of Darkness, who almost always played a principal part in these scriptural dramas.—Quarterly Review.

SPIRIT OF DISCOVERY

BIRMINGHAM RAILWAY

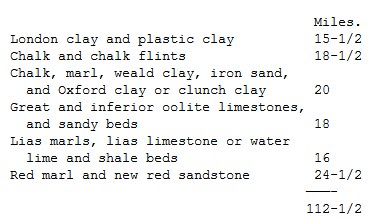

The line of the proposed plan for this useful and excellent undertaking has been forwarded to us. We know not whether the projectors are aware that a straight line is no longer necessary, but that the sharpest turns may now be made on rail-roads by an American invention, lately carried into effect in the United States with singular success.—The line of railway will be 112-1/2 miles. Birmingham being between 3 and 400 feet higher than London, and the intervening ground much broken, the railway could not be laid down without an inclination in its planes; the rise, however, will in no case exceed 1 in 330. The highest point of the line is on the summit of an inclined plane 15 miles long, rising 13-1/3 feet in each mile, and is 315 feet above the level at Maiden Lane, London; from which it is distant 31 miles. The termination at Birmingham is 256 feet higher than the commencement at London. It is intended that there should be 10 tunnels—one at Primrose Hill half a mile long, one near Watford a mile long, and one near Kilsby, 78 miles from London, a mile and a quarter long. The others are each less than a quarter of a mile in length, with the exception of one, which is a third of a mile long. They will all be 25 feet in height, well lighted, and ought rather to be called galleries than tunnels. The strata through which the railway is carried, appear generally to follow in this order from London:

The railway will be composed of two lines of rails with a space between them of six feet, but at particular points two additional lines will be required as turns-out to facilitate the passage of the locomotive engines and carriages. If we assume the average rate of travelling on the railway to be 20 miles an hour, (which is about the mark,) that 1,200 persons pass along it in a day, and 120 are conveyed in each train of carriages, then only ten trains of carriages would be required for all the passengers; each train would separately take a minute and a half, and the ten trains not more than fifteen minutes in passing over half a mile of ground. Allow twice this time for the passage of cattle and merchandise, and it is manifest that the traffic on railways can never be a source of annoyance to persons residing near them. All who have travelled in carriages drawn by locomotive steam-engines on the Liverpool and Manchester railway can vouch for the safety and comfort, as well as the expedition, of this mode of conveyance; but the strongest evidence of public opinion on this subject is the fact, that twice as many persons go by the railway, as were formerly carried in coaches running on the roads between the two places—and yet, although the expense of travelling is reduced one-half, and the works of the railway cost more than 800,000l., the proprietors are in the receipt of a dividend of 9l. for a year on their 100l. shares! Enough has been ascertained of the traffic in the districts through which the London and Birmingham Railway will pass, to remove all doubt as to an ample return for the necessary outlay.—Metropolitan.

THE GATHERER

A Dancing Archbishop.—Dr. King, Archbishop of Dublin, having invited several persons of distinction to dine with him, had, amongst a great variety of dishes, a fine leg of mutton and caper sauce; but the doctor, who was not fond of butter, and remarkable for preferring a trencher to a plate, had some of the abovementioned pickle introduced dry for his use; which, as he was mincing, he called aloud to the company to observe him; "I here present you, my lords and gentlemen," said he, "with a sight that may henceforward serve you to talk of as something curious, namely, that you saw an Archbishop of Dublin, at fourscore and seven years of age, cut capers upon a trencher."

T.H.

Singular Parish.—In the parish of East Twyford, near Harrow, in the county of Middlesex, there is only one house, and the farmer who occupies it is perpetual churchwarden of a church which has no incumbent, and in which no duty is performed. The parish has been in this state ever since the time of Queen Elizabeth.

H.S.S.

Scandal.—It is as well not to trust to one's gratitude after dinner. I have heard many a host libelled by his guests, with his Burgundy yet reeking on their rascally lips.—Lord Byron.

A lady with a well plumed head dress, being in deep conversation with a naval officer, one of the company said, "it was strange to see so fine a woman tar'd and feathered."

A Scolding Wife.—Dr. Casin having heard the famous Thomas Fuller repeat some verses on a scolding wife, was so delighted with them, as to request a copy. "There is no necessity for that," said Fuller, "as you have got the original."

Bouts Rimés are words or syllables which rhyme, arranged in a particular order, and are given to a poet with a subject, on which he must write verses ending in the same rhymes, disposed in the same order. Menage gives the following account of the origin of this ridiculous conceit. Dulot, (a poet of the 17th century,) was one day complaining in a large company, that 300 sonnets had been stolen from him. One of the company expressing his astonishment at the number, "Oh," said he, "they are blank sonnets, or rhymes (bouts rimés) of all the sonnets I may have occasion to write." This ludicrous story produced such an effect, that it became a fashionable amusement to compose blank sonnets, and in 1648, a quarto volume of bouts rimés was published.

Poisoned Arrows used in Guiana are not shot from a bow, but blown through a tube. They are made of the hard substance of the cokarito tree, and are about a foot long, and the size of a knitting-needle. One end is sharply pointed, and dipped in the poison of worraia, the other is adjusted to the cavity of the reed, from which it is to be blown by a roll of cotton. The reed is several feet in length. A single breath carries the arrow 30 or 40 yards.

Sterling Applause.—Lord Bolingbroke was so pleased with Barton Booth's performance of Cato, at Drury Lane Theatre, in 1712, that he presented the actor with fifty guineas from the stage-box—an example which was immediately followed by Bolingbroke's political opponents.

Claret has been accused of producing the gout, but without reason. Persons who drench themselves with Madeira, Port, &c. and indulge in an occasional debauch of Claret, may indeed be visited in that way; because a transition from the strong brandied wines to the lighter, is always followed by a derangement of the digestive organs.

Quarantine in America.—Dr. Richard Bayley is the person to whom New York is chiefly indebted for its quarantine laws. His death was, however, by contagion. In August, 1801, Doctor Bayley, in the discharge of his duty as health physician, enjoined the passengers and crew of an Irish emigrant ship, afflicted with the ship fever, to go on shore to the rooms and tents appointed for them, leaving their luggage behind. The next morning, on going to the hospital, he found that both crew and passengers, well, sick, and dying, were huddled together in one apartment, where they had passed the night. He inconsiderately entered this room before it had been properly ventilated, but remained scarcely a moment, being obliged to retire by a deadly sickness at the stomach, and violent pain in the head, with which he was suddenly seized. He returned home, retired to bed, and in the afternoon of the seventh day following, he expired.

Shaving is said to have come into use during the reigns of Louis XIII. and XIV. of France, both of whom ascended the throne without a beard. Courtiers and citizens then began to shave, in order to look like the king, and, as France soon took the lead in all matters of fashion on the continent, shaving became general. It is at best a tedious operation. Seume, a German author, says, in his journal, "To-day I threw my powder apparatus out of the window, when will come the blessed day that I shall send the shaving apparatus after it."

Book Morality.—Dr. Beddoes wrote a history of Isaac Jenkins, which was intended to impress useful moral lessons on the labouring classes in an attractive manner. Above 40,000 copies of this work were sold in a short time.

The Bedford Missal throws even the costly scrap-books of these times into the shade. It was made for the celebrated John, Duke of Bedford, (one of the younger sons of Henry IV.) and contains 59 large, and more than 1,000 small miniature paintings.

The Bedford Level was drained at an expense of £400,000. by the noble family of Russell, Earls and Dukes of Bedford, and others; by which means 100,000 acres of good land have been brought into use.

1

For Views of Windsor Castle, with the late renovations, see the following Numbers of the Mirror:

No. 292, George the Fourth's Gateway, South and East Sides.

Long Gallery.

No. 437, Bedchamber in which George IV. died.

No. 444, Private Dining Room.

No. 486, George IV. Gateway, from the interior of the Quadrangle.

No. 488, St. George's Chapel.

2

United Service Journal, Jan. 1832.

3

This disadvantage is greater on the stage, since the audience neither see nor hear more of Bourbon, and only four acts of the piece are performed. In the closet it will not be so obvious, as Bourbon returns in the fifth act.

4

This is an entire variation from history.

5

It is related in the life of St. Bernard, that his pale and emaciated appearance, and the animation and the fire, which seemed to kindle his whole being as he spoke, made so deep an impression on those who could only see him and hear his voice, that Germans, who understand not a word of his language, were often moved to tears.—Neander, Der Heilige Bernard, p. 49.