полная версия

полная версияThe Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 19, No. 539, March 24, 1832

THE BELL ROCK LIGHT HOUSE

On the 9th ult., about 10 P.M., a large herring-gull struck one of the south-eastern mullions of the Bell Rock Light House with such force, that two of the polished plates of glass, measuring about two feet square, and a quarter of an inch in thickness, were shivered to pieces and scattered over the floor in a thousand atoms, to the great alarm of the keeper on watch, and the other two inmates of the house, who rushed instantly to the light room. It fortunately happened, that although one of the red-shaded sides of the reflector-frame was passing in its revolution at the moment, the pieces of broken glass were so minute, that no injury was done to the red glass. The gull was found to measure five feet between the tips of the wings. In his gullet was found a large herring, and in its throat a piece of plate-glass, of about one inch in length.—(From No. I. of the Nautical Magazine, a work of clever execution, great promise, and extraordinary cheapness.)

NO CHALK

It appears that the bill for the abolition of imprisonment for debt in America "works well," as applied to New York; and the system is consequently to be put in general force all over the Union—a fact, which, as a poet like Mr. Watts would say, adds another leaf to America's laurel. But the paper which announced this gratifying intelligence, relates in a paragraph nearly subjoined to it, a circumstance in natural history that seems to have some connexion with the affairs between debtor and creditor in the United States. It informs us, that up to the present period of scientific investigation, "no chalk has been discovered in North America." Now this is really a valuable bit of discovery; and we heartily wish that the Geological Society, instead of wasting their resources on anniversary-dinners, as they have lately been doing, would at once set about establishing the proof of a similar absence of that article in this country. Surely, our brethren on the other side of the Atlantic, will not fail to take the hint which nature herself has so benificently thrown out to them; and instead of abolishing the power of getting into prison, put an end at once to the power of getting into debt. The scarcity of chalk ought certainly to be numbered among the natural blessings of America. Had the soil on that side of the ocean been as chalky as this, America might have been visited by a comet, like Pitt, with a golden train of eight hundred millions.—Monthly Magazine.

THE NATURALIST

ANGLING

(From the Angler's Museum, quoted in the Magazine of Natural History.)Every one who is acquainted with the habits of fish is sensible of the extreme acuteness of their vision, and well knows how easily they are scared by shadows in motion, or even at rest, projected from the bank; and often has the angler to regret the suspension of a successful fly-fishing by the accidental passage of a person along the opposite bank of the stream: yet, by noting the apparently trivial habits of one of nature's anglers, not only is our difficulty obviated, but our success insured. The heron, guided by a wonderful instinct, preys chiefly in the absence of the sun; fishing in the dusk of the morning and evening, on cloudy days and moonlight nights. But should the river become flooded to discoloration, then does the "long-necked felon" fish indiscriminately in sun and shade; and in a recorded instance of his fishing on a bright day, it is related of him, that, like a skilful angler, he occupied the shore opposite the sun.

SKILFUL ANATOMISTS

(For the Mirror.)It may not be generally known that the tadpole acts the same part with fish that ants do with birds; and that through the agency of this little reptile, perfect skeletons, even of the smallest fishes may be obtained. To produce this, it is but necessary to suspend the fish by threads attached to the head and tail in an horizontal position, in a jar of water, such as is found in a pond, and change it often, till the tadpoles have finished their work. Two or three tadpoles will perfectly dissect a fish in twenty-four hours.

H.S.S.

THREE ENTHUSIASTIC NATURALISTS

The first is a learned entomologist, who, hearing one evening at the Linnean Society that a yellow Scarabaeus, otherwise beetle, of a very rare kind was to be captured on the sands at Swansea, immediately took his seat in the mail for that place, and brought back in triumph the object of his desire. The second is Mr. David Douglas, who spent two years among the wild Indians of the Rocky Mountains, was reduced to such extremities as occasionally to sup upon the flaps of his saddle; and once, not having this resource, was obliged to eat up all the seeds he had collected the previous forty days in order to appease the cravings of nature. Not appalled by these sufferings, he has returned again to endure similar hardships, and all for a few simples. The third example is Mr. Drummond, the assistant botanist to Franklin in his last hyperborean journey. In the midst of snow, with the thermometer 15° below zero, without a tent, sheltered from the inclemency of the weather only by a hut built of the branches of trees, and depending for subsistence from day to day on a solitary Indian hunter, "I obtained," says this amiable and enthusiastic botanist, "a few mosses; and, on Christmas day,"—mark, gentle reader, the day, of all others, as if it were a reward for his devotion,—"I had the pleasure of finding a very minute Gymnóstomum, hitherto undescribed. I remained alone for the rest of the winter, except when my man occasionally visited me with meat; and I found the time hang very heavy, as I had no books, and nothing could be done in the way of collecting specimens of natural history."

Magazine of Natural History

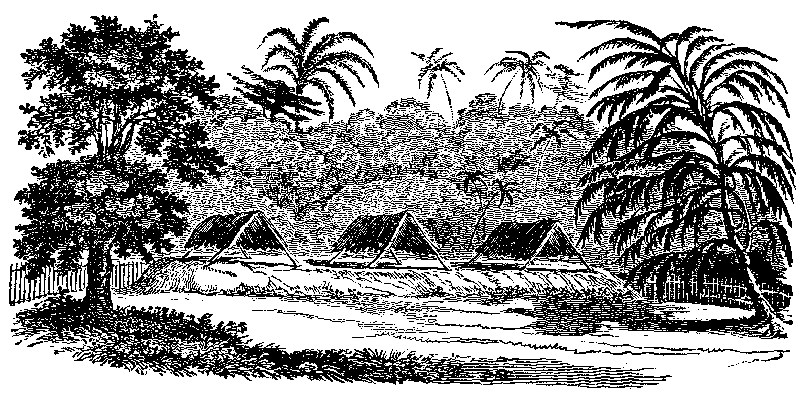

BURIAL PLACE IN TONGATABU

This is another of Mr. Bennett's sketches made during his recent visit to several of the Polynesian Islands. It represents the burial-place of the Chiefs of Tongatabu: over this "earthly prison of their bones," we may say with Titus Andronicus:

In pence and honour rest you here my sons:(The) readiest champions, repose you here,Secure from worldly chances and mishaps:Here lurks no treason, here no envy swells,Here grow no damned grudges: here are no storms,No noise, but silence and eternal sleep.Mr. Bennett thus describes the spot, with some interesting circumstances:

"July 29th. I visited this morning a beautiful spot named Maofanga, at a short distance from our anchorage; here was the burial-place of the chiefs. The tranquillity of this secluded spot, and the drooping trees of the casuarina equisetifolia, added to the mournful solemnity of the place. Off this place, the Astrolabe French discovery ship lay when, some time before, she fired on the natives. The circumstances respecting this affair, as communicated to me, if correct, do not reflect much credit on the commander of the vessel. They are as follow: During a gale the Astrolabe drove on the reef, but was afterwards got off by the exertion of the natives; some of the men deserting from the ship, the chiefs were accused of enticing them away, and on the men not being given up the ship fired on the village; the natives barricaded themselves on the beach by throwing up sand heaps, and afterwards retired into the woods. The natives pointed out the effects of the shot; on the trees, a large branch of a casuarina tree in the sacred enclosure was shot off, several coco-nut trees were cut in two, and the marks of several spent shots still remain on the trees: three natives were killed in this attack. A great number of the flying-fox, or vampire bat, hung from the casuarina trees in this enclosure, but the natives interposed to prevent our firing at them, the place being tabued. Mr. Turner had been witness to the interment here, not long previously, of the wife of a chief, and allied to the royal family. The body, enveloped in mats, was placed in a vault, in which some of her relations had been before interred, and being covered up, several natives advanced with baskets of sand, &c. and strewed it over the vault; others then approached and cut themselves on the head with hatchets, wailing and showing other demonstrations of grief. Small houses are erected over the vaults. All the burial-places are either fenced round or surrounded by a low wall of coral stones, and have a very clean, neat, and regular appearance.

"I observed that nearly the whole of the natives whom I had seen, were deficient in the joints of the little finger of the left hand, and some of both; some of the first joint only, others two, and many the whole of both fingers. On inquiry, I found that a joint is chopped off on any occasion of the illness or death of a relation or chief, as a propitiatory offering to the Spirit. There is a curious analogy between this custom and one related by Mr. Burchell as existing among the Bushmen tribe in Southern Africa, and performed for similar superstitious reasons to express grief for the loss of relations.

"Near this place was the Hufanga, or place of refuge, in which a person in danger of being put to death is in safety as long as he remains there; on looking in the enclosure, it was only a place gravelled over, in which was a small house and some trees planted." 2

THE SELECTOR; AND LITERARY NOTICES OF NEW WORKS

FRANCIS THE FIRST

An Historical Drama. By Frances Ann KembleThis extraordinary production has awakened an interest in the dramatic and literary world, scarcely equalled in our times. We know of its fortune upon the stage by report only; but, from our acquaintance with the requisites of the acting drama, we should conceive its permanence will be more problematical in the theatre than in the closet; and considering the conditions upon which dramatic fame is now attainable, we think the clever authoress will not have reason to regret these inequalities of success. That Miss Kemble's tragedy possesses points to be made, and passages that will tell on the stage, cannot be denied; but its interest for representation requires to be concentrated; it "wants a hero, an uncommon thing." It is well observed in the Quarterly Review, (by the way, the only notice yet taken of the tragedy, that merits attention,) that "the piece is crowded with characters of the greatest variety, all of considerable importance in the piece, engaged in the most striking situations, and contributing essentially to the main design. Instead of that simple unity of interest, from which modern tragic writers have rarely ventured to depart, it takes the wider range of that historic unity, which is the characteristic of our elder drama; moulds together, and connects by some common agent employed in both, incidents which have no necessary connexion; and—what in the present tragedy strikes us as on many accounts especially noticeable—unites by a fine though less perceptible moral link, remote but highly tragic events with the immediate, if we may so speak, the domestic interests of the play." This language is finely characteristic of the drama. Again, the interest has "so much Shakspearianism in the conception as to afford a remarkable indication of the noble school in which the young authoress has studied, and the high models which, with courage, in the present day, fairly to be called originality, she has dared to set before her. In fact, Francis the First is cast entirely in the mould of one of Shakspeare's historical tragedies." The drama too was written without any view to its representation, as the Quarterly reviewer has been "informed by persons who long ago perused the manuscript, several years before Miss Kemble appeared upon the stage, and at a time when she little anticipated the probability that she herself might be called upon to impersonate the conceptions of her own imagination. We believe that we are quite safe when we state that the drama, in its present form, was written when the authoress was not more than seventeen." Yet it should be added that the above statement is not made by way of extenuation; for, to say the truth, it needs no such adventitious aid.

A mere outline of the story will convince the reader that, as the Reviewer states, "the tragedy is alive from the beginning to the end;" and our extracts will we trust show the language to be bold and vigorous; the imagery sweetly poetical; and the workings of the passions which actuate the personages to be evidently of high promise if not of masterly spirit.

The tragedy opens with the recall of the Constable De Bourbon from Italy, through the supposed political intrigue, but really, the secret love, of the mother of Francis, Louisa of Savoy, Duchess of Angouleme, whom Miss Kemble calls the Queen Mother. In the second scene the Queen Mother communicates to Gonzales, a monk in disguise, but in, reality an emissary of the Court of Spain, her secret passion for De Bourbon, and her design in his recall.

Francis is introduced at a tourney, where he not only triumphs in the jousts, but over the heart of the beautiful Françoise de Foix.

Bourbon returns, and the second act opens with his interview with Renée, (or Margaret,) the daughter of the Queen Mother, and sister of Francis I., for whom he really entertains an affection. In the second scene the Queen Mother declares her passion to Bourbon, who, at first supposes he is to be tempted by Margaret's hand, but finding the Queen herself to be the lure, he indignantly rejects her. The character of Bourbon in this scene is admirably brought out. The artifice of the Queen—the scorn of Bourbon—and the Queen's meditated vengeance are powerfully wrought:

BOURBON.

I would have you know,De Bourbon storms, and does not steal his honoursAnd though your highness thinks I am ambitious,(And rightly thinks) I am not so ambitiousEver to beg rewards that I can win,—No man shall call me debtor to his tongue.QUEEN (rising.)

'Tis proudly spoken; nobly too—but what—What if a woman's hand were to bestowUpon the Duke de Bourbon such high honours,To raise him to such state, that grasping man,E'en in his wildest thoughts of mad ambition,Ne'er dreamt of a more glorious pinnacle?BOURBON.

I'd kiss the lady's hand, an she were fair.But if this world fill'd up the universe,—If it could gather all the light that livesIn ev'ry other star or sun, or world;If kings could be my subjects, and that ICould call such pow'r and such a world my own,I would not take it from a woman's hand.Fame is my mistress, madam, and my swordThe only friend I ever wooed her with.I hate all honours smelling of the distaff,And, by this light, would as lief wear a spindleHung round my neck, as thank a lady's handFor any favour greater than a kiss.—QUEEN.

And how, if such a woman loved you,—howIf, while she crown'd your proud ambition, sheCould crown her own ungovernable passion,And felt that all this earth possess'd, and sheCould give, were all too little for your love?Oh good, my lord! there may be such a woman.BOURBON (aside.)

Amazement! can it be, sweet Margaret—That she has read our love?—impossible!—and yet—That lip ne'er wore so sweet a smile!—it is.That look is pardon and acceptance! (aloud)—speak. (He falls at the Queen's feet.)Madam, in pity speak but one word more,—Who is that woman?QUEEN (throwing off her veil.)

I am that woman!BOURBON (starting up.)

You, by the holy mass! I scorn your proffers;Is there no crimson blush to tell of fameAnd shrinking womanhood! Oh shame! shame! shame!(The Queen remains clasping her hands to her temples, while De Bourbon walks hastily up and down; after a long pause the Queen speaks.)

(The Queen summons her Confessor.)

Enter GONZALES.

Sir, we have business with this holy father;You may retire.BOURBON.

Confusion!QUEEN.

Are we obeyed?BOURBON (aside.)

Oh Margaret!—for thee! for thy dear sake![Rushes out. The Queen sinks into a chair.]

QUEEN.

Refus'd and scorn'd! Infamy!—the word chokes me!How now! why stand'st thou gazing at me thus?GONZALES.

I wait your highness' pleasure.—(Aside) So all is well—A crown hath fail'd to tempt him—as I seeIn yonder lady's eyes.QUEEN.

Oh sweet revenge!Thou art my only hope, my only dower,And I will make thee worthy of a Queen.Proud noble, I will weave thee such a web,—I will so spoil and trample on thy pride,That thou shalt wish the woman's distaff wereTen thousand lances rather than itself.Ha! waiting still, sir Priest! Well as them seestOur venture hath been somewhat baulk'd,—'tis notEach arrow readies swift and true the aim,—Love having failed, we'll try the best expedient,That offers next,—what sayst thou to revenge?'Tis not so soft, but then 'tis very sure;Say, shall we wring this haughty soul a little?Tame this proud spirit, curb this untrain'd charger?We will not weigh too heavily, nor grindToo hard, but, having bow'd him to the earth,Leave the pursuit to others—carrion birds,Who stoop, but not until the falcon's gorg'dUpon the prey he leaves to their base talons.GONZALES.

It rests but with your grace to point the means.QUEEN.

Where be the plans of those possessionsOf Bourbon's house?—see that thou find them straight:His mother was my kinswoman, and ICould aptly once trace characters like thoseShe used to write—enough—Guienne—AuvergneAnd all Provence that lies beneath his claim,—That claim disprov'd, of right belong to me.—The path is clear, do thou fetch me those parchments.[Exit Gonzales.

Not dearer to my heart will be the dayWhen first the crown of France deck'd my son's forehead,Than that when I can compass thy perdition,—When I can strip the halo of thy fameFrom off thy brow, seize on the wide domains,That make thy hatred house akin to empire,And give thy name to deathless infamy. [Exit.The King holds a Council to appoint a successor to the Constable in Italy. This scene is of stirring interest. The Queen goads the high-minded Bourbon nigh unto madness, and at length breaks out into open insult. Lautrec the brother of Françoise, and despised by Bourbon, is named the governor. In the ceremony Francis addresses Lautrec:—

FRANCIS.

With our own royal hand we'll buckle onThe sword, that in thy grasp must be the bulwarkAnd lode-star of our host. Approach.QUEEN.

Not so.Your pardon, sir; but it hath ever beenThe pride and privilege of woman's handTo arm the valour that she loves so well:We would not, for your crown's best jewel, bateOne jot of our accustom'd state to-day:Count Lautrec, we will arm thee, at our feet:Take thou the brand which wins thy country's wars,—Thy monarch's trust, and thy fair lady's favour.Why, how now!—how is this!—my lord of Bourbon!If we mistake not, 'tis the sword of officeWhich graces still your baldrick;—with your leave,We'll borrow it of you.BOURBON (starting up.)

Ay, madam, 'tis the swordYou buckled on with your own hand, the dayYou sent me forth to conquer in your cause;And there it is;—(breaks the sword)—take it—and with it allTh' allegiance that I owe to France; ay take it;And with it, take the hope I breathe o'er it:That so, before Colonna's host, your armsLie crush'd and sullied with dishonour's stain;So, reft in sunder by contending factions,Be your Italian provinces; so tornBy discord and dissension this vast empire;So broken and disjoin'd your subjects' loves;So fallen your son's ambition, and your pride.QUEEN (rising.)

What ho—a guard within there—Charles of Bourbon,I do arrest thee, traitor to the crown.Enter Guard.

Away with yonder wide-mouth'd thunderer;We'll try if gyves and straight confinement cannotCheck this high eloquence, and cool the brainWhich harbours such unmannerd hopes.[Bourbon is forced out.

Dream ye, my lords, that thus with open ears,And gaping mouths and eyes, ye sit and drinkThis curbless torrent of rebellious madness.And you, sir, are you slumbering on your throne;Or has all majesty fled from the earth,That women must start up, and in your councilSpeak, think, and act for ye; and, lest your vassals,The very dirt beneath your feet, rise upAnd cast ye off, must women, too, defend ye?For shame, my lords, all, all of ye, for shame,—Off, off with sword and sceptre, for there isNo loyalty in subjects; and in kings,No king-like terror to enforce their rights.Meanwhile Lautrec proposes to his sister Françoise, the hand of his friend, the gallant Laval; whilst the fair maiden is importuned by Francis, who endeavours to make the poet Clement Marot the bearer of his intrigue. In a scene between Francis and the poet, the licentious impatience of the King, and the unsullied honour of Clement are finely contrasted.

FRANCIS.

I would I'd borne the scroll myself, thy wordsImage her forth so fair.CLEMENT.

Do they, indeed?Then sorrow seize my tongue, for, look you, sir,I will not speak of your own fame or honour,Nor of your word to me: king's words, I find,Are drafts on our credulity, not pledgesOf their own truth. You have been often pleas'dTo shower your royal favours on my head;And fruitful honours from your kindly willHave rais'd me far beyond my fondest hopes;But had I known such service was to beThe nearest way my gratitude might takeTo solve the debt, I'd e'en have given backAll that I hold of you: and, now, not e'enYour crown and kingdom could requite to meThe cutting sense of shame that I endur'dWhen on me fell the sad reproachful glanceWhich told me how I stood in the esteemOf yonder lady. Let me tell you, sir,You've borrow'd for a moment what whole yearsCannot bestow—an honourable name.Now fare you well; I've sorrow at my heart,To think your majesty hath reckon'd thusUpon my nature. I was poor before,Therefore I can be poor again withoutRegret, so I lose not mine own esteem.FRANCIS.

Excellent.Oh, ye are precious wooers, all of ye.I marvel how ye ever ope your lipsUnto, or look upon that fearful thing,A lovely woman.CLEMENT.

And I marvel, sir,At those who do not feel the majesty,—By heaven, I'd almost said the holiness,—That circles round a fair and virtuous woman:There is a gentle purity that breathesIn such a one, mingled with chaste respect,And modest pride of her own excellence,—A shrinking nature, that is so adverseTo aught unseemly, that I could as soonForget the sacred love I owe to heav'n,As dare, with impure thoughts, to taint the airInhal'd by such a being: than whom, my liege,Heaven cannot look on anything more holy,Or earth be proud of anything more fair. [Exit.Gonzales, the monk, is despatched by the Queen to Bourbon in prison. At the door he meets Margaret, who had bribed her way to her lover, and was returning after ineffectual attempts to soothe him into submission, shame-struck at the exposure of her mother's guilt. The Queen intrusts Gonzales with a signet ring as the means of liberating him and conducting him to the royal chamber. Bourbon is immovable; and in revenge upon the Court, he falls in with a private scheme of Gonzales, which is to accept of his liberty, and set off to the Court of Spain. The undisguising of the treacherous monk is in these powerful lines:

GONZALES.

Now,That day is come, ay, and that very hour:Now shout your war-cry; now unsheath your sword;I'll join the din, and make these tottering wallsTremble and nod to hear our fierce defiance.Nay, never start, and look upon my cowl—You love not priests, De Bourbon, more than I.Off, vile denial of my manhood's pride;Off, off to hell! where thou wast first invented,Now once again I stand and breathe a knight.Nay, stay not gazing thus: it is Garcia,Whose name hath reach'd thee long ere now, I trow;Whom thou hast met in deadly fight full oft,When France and Spain join'd in the battle field.Beyond the Pyrenean boundaryThat guards thy land, are forty thousand men:Their unfurl'd pennons flout fair France's sun,And wanton in the breezes of her sky:Impatient halt they there; their foaming steeds,Pawing the huge and rock-built barrier,That bars their further course—they wait for thee:For thee whom France hath injur'd and cast off;For thee, whose blood it pays with shameful chains,More shameful death; for thee, whom Charles of SpainSummons to head his host, and lead them onTo conquest and to glory.The interest now reverts to the fate of Françoise, and Bourbon is lost sight of; a transition which, both in acting and reading, endangers the drama. 3 News arrives of the flight of Lautrec from his government; of his arrest, his imprisonment, and capital condemnation. 4 He enjoins his sister to intercede in his behalf with Francis; she complies, but it is at the expense of her honour; broken-hearted, she sinks beneath her shame at the crime into which she has been betrayed, and returns home. Francis pursues her, and the Queen, now aware of his passion for her, dispatches the monk Gonzales on a secret mission to poison Françoise, who, she fears, may supplant her in her ascendancy over the King. A fine passage occurs in the scene wherein the Queen proposes her scheme to Gonzales.