полная версия

полная версияThe Journal of Negro History, Volume 1, January 1916

To satisfy themselves as to their safety they proceeded to break open the hatchways when, so suddenly as to create something of a panic, Richard Edmondson bounded on deck and in a voice of suppressed excitement exclaimed, "Do yourselves no harm, gentlemen, for we are all here!" Richard was young, muscular and of splendid proportions and seeing him thus by the poor light of smoky lanterns, with flashing eyes and swinging arms, leaping into their midst with an unknown number of others following, some of the masters experienced a feeling of terror, and dropping their guns, scurried away to safety among the dark shadows of the vessel.

By the time the others reached the deck, the shock of Richard's strange appearance had somewhat died away and when Samuel, who was one of the last, appeared, a sharp blow which, but for a sudden lurch of the vessel, would have laid him low fell on one side of his head. Drayton and Sayres,260 who were witnesses of this incident, were horrified to think that, having not so much as a penknife with which to defend themselves, these poor creatures might be brutally murdered, and, notwithstanding the serious aspect of their own fortunes,261 protested vigorously against such violence. But for this timely interference, there is but little doubt that some of these poor people would have been cruelly if not fatally injured.

The true condition of affairs, however, was speedily recognized and seeing there was nothing to fear in the way of resistance, order was soon evolved out of the general chaos and then came the decision to make an early start on the return trip. Among the slaves, the reaction from a feeling of hope and joyous anticipation of the delights of freedom was terrible indeed. The bitter gall and wormwood of failure was the sad and gloomy portion of these seventy and seven souls. Among them then there were but few who were not completely crushed, their minds a seething torrent, in which regret, misery and despair made battle for the mastery. Children weeping and wailing clung to the skirts of their elders. The women with shrieks, groans and tearful lamentations deplored their sad fate, while the men, securely chained wrist and wrist together, stood with heads dropped forward, too dazed and wretched for aught but to turn their stony gaze within upon the wild anguish of their aching hearts.

Their arrival at Washington was signalized by a demonstration vastly different but little short of that which had taken place a few days before. The wharves were alive with an eager and excited throng all intent upon a view of the miserable folks who had been guilty of so ungrateful an effort. So disorderly was the mob that the debarkation was for some time delayed. This was finally accomplished through the strenuous efforts of the entire constabulary of the city.

The utmost watchfulness and care was, however, unavailing to prevent assaults. The most serious instance of this kind was the act of an Irish ruffian, who so far forgot the traditions and sufferings of his own people as to cast himself upon Drayton with a huge dirk and cut off a piece of his ear.262 For a few moments all the horrors incident to riot and bloodshed were in evidence. The air was filled with the screams of terrorized women and children and the curses and threats of vengeful men. The whole was a struggling, swaying mass, which for a season had been swept beyond itself by brutish passion.

Numerous arrests were made and in due course the march to the jail was begun with the accompanying crowd hurling taunts and jeers at every step. While they were proceeding thus, an onlooker said to Emily, "Aren't you ashamed to run away and make all this trouble for everybody?" To this she replied, "No sir, we are not and if we had to go through it again, we'd do the same thing."

The controversy that was precipitated through the attempted escape, between the advance guard of abolition and the defenders of slavery, was most bitter and violent. The storm broke furiously about the offices of The National Era. In Congress, Mr. Giddings of Ohio moved an "inquiry into the cause of the detention at the District jail of persons merely for attempting to vindicate their inalienable rights." Senator Hale of New Hampshire moved a resolution of "inquiry into the necessity for additional laws for the protection of property in the District."263 A committee consisting of such notable characters as the Channings, Samuel May, Samuel Howe, Richard Hildreth, Samuel Sewell and Robert Morris, Jr., was formed at Boston to furnish aid and defense for Drayton. These men were empowered to employ counsel and collect money. Horace Mann, William H. Seward, Salmon P. Chase and Fessenden of Maine volunteered to serve gratuitously.264

Other philanthropists directed their attention to the liberation of these slaves. The Edmondsons were owned by an estate. The administrator, who was approached by John Brent,265 the husband of the oldest sister of the children, agreed to give their friends an opportunity to effect their purchase, as he was unwilling to run any further risk by keeping them. He failed to keep this promise and when Mr. Brent went to see them the next day he was informed that they had been sold to Bruin and Hill, the slave-dealers of Alexandria and Baltimore, and had been sent to the former city. A cash sum of $4,500 had been accepted for the six children and when taxed with the failure to keep his promise, he simply said he was unwilling to take any further risk with them. Bruin also refused to listen to any proposals, saying he had long had his eyes on the family and could get twice what he paid for them in the New Orleans market.

They were first taken to the slave pens at Alexandria, where they remained nearly a month. Here the girls were required to do the washing for a dozen or more men with the assistance of their brothers and were at length put aboard a steamboat and taken to Baltimore where they remained three weeks. Through the exertions of friends at Washington, $900 was given towards their freedom by a grandson of John Jacob Astor, and this was appropriated towards the ransom of Richard, as his wife and children were said to be ill and suffering at Washington. The money arrived on the morning they were to sail for New Orleans but they had all been put aboard the brig Union, which was ready to sail, and the trader refused to allow Richard to be taken off. The voyage to New Orleans covered a period of seven days, during which much discomfort and suffering were experienced. There were eleven women in the party, all of whom were forced to live in one small apartment, and the men numbering thirty-five or forty, in another not much larger. Most of them being unaccustomed to travel by water were afflicted with all the horrors of sea-sickness. Emily's suffering from this cause was most pitiable and so serious was her condition at one time that the boys feared she would die. The brothers, however, as in all circumstances, were very kind and would tenderly carry her out on deck whenever the heat in their close quarters became too oppressive and would buy little comforts that were in their reach and minister in all possible ways to her relief.

In due course they arrived at New Orleans and were immediately initiated into the horrors of a Georgia pen. The girls were required to spend much time in the show room, where purchasers came to examine them carefully with a view to buying them. On one occasion a youthful dandy had applied for a young person whom he wished to install as housekeeper and the trader decided that Emily would just about meet the requirements, but when he called her she was found to be indulging in a fit of weeping. The youth, therefore, refused to consider her, saying that he had no room for the snuffles in his house. The loss of this transaction so incensed the trader, who said he had been offered $1,500 for the proper person, that he slapped Emily's face and threatened to send her to the calaboose, if he found her crying again.

Here also the boys had their hair closely cropped and their clothes, which were of good material, exchanged for suits of blue-jeans. Appearing thus, they were daily exhibited on the porch for sale. Richard, who was in reality free, as his purchase money was on deposit in Baltimore, was allowed to come and go at will and early bent his energies toward the discovery of their elder brother Hamilton,266 who was living somewhere in the city. His quest was soon rewarded with success and one day to the delight of his sisters and brothers he brought him to see them. Hamilton had never seen Emily, as he had been sold away from his parents before her birth, but his joy, though mingled with sorrow, could not be suppressed. He was soon busy with plans for the increase of their meager comforts. Finding upon inquiry that Hamilton was thoroughly responsible, the trader consented to the girls' spending their nights at their brother's home. He was also at pains to secure good homes for the unfortunate group and was successful in inducing a wealthy Englishman to purchase his brother Samuel.

In consequence of an epidemic of yellow fever, which increased in virulence from day to day, the traders decided to bring the slaves North without further delay and so a few days later they were reembarked on the brig Union with Baltimore as their destination. Samuel was the only one of the brothers and sisters left behind. As he was pleasently situated with humane and kindly owners, the parting from him was not so sad as otherwise it might have been. Sixteen days were required for the trip and upon their arrival they were again placed in the same old prison. Richard was almost immediately freed and, in company with a Mr. Bigelow, of Washington, was enabled to rejoin his wife and children.

Paul Edmondson visited his children at the Baltimore jail in company with their sister.267 He had been encouraged to hope that in some way a fund might be raised for their ransom, but it was not until some weeks later, after they had been returned through Washington and again placed in their old slave quarters at Alexandria, that an understanding as to terms could be had with Bruin and Hill. They finally agreed to accept $2,250 if the amount was raised within a certain time and gave Paul a signed statement of the terms, which might be used as his credentials in the matter of soliciting assistance. Armed with this document, he arrived at New York and found his way to the Anti-Slavery office, where the price demanded was considered so exorbitant that but little encouragement was given him. From here he went to the home of Rev. Henry Ward Beecher, where he arrived foot-sore and weary. After ringing the bell, he sat upon the doorstep weeping. Here Mr. Beecher found him and, taking him into his library, inquired his story.

As a result there followed a public meeting in Mr. Beecher's Brooklyn church, at which he pleaded passionately as if for his own children, while other clergymen spoke with equal interest and feeling. The money was raised, an agent appointed to consummate the ransom of the children, and Paul, with a sense of happiness and relief to which he had long been a stranger, started with the good news on his way homeward.

Meanwhile the girls were torn with doubt and anxiety as to the success of their father's mission. Several weeks had elapsed and the traders were again getting together a coffle of slaves for shipment to the slave market, this time to that in South Carolina. The girls, too, had been ordered to be in readiness and the evening before had broken down in tears when Bruin's young daughter, who was a favorite with the girls, sought them out and pleaded with them not to go. Emily told her to persuade her father not to send them and so she did, while clinging around his neck until he had not the heart to refuse.

A day or two later, while looking from their window, they caught sight of their father and ran into his arms shouting and crying. So great was their joy that they did not notice their father's companion, a Mr. Chaplin, the agent appointed at the New York meeting to take charge of the details of their ransom. These were soon completed, their free papers signed and the money paid over. Bruin, too, it is said, was pleased with the joy and happiness in evidence on every hand and upon bidding the girls good-bye gave each a five dollar gold piece.

Upon their arrival at Washington they were taken in a carriage to their sister's home, whence the news of their deliverance seemed to have penetrated to every corner of the neighborhood with the result that it was far into the night before the last greetings and congratulations had been received and they were permitted, in the seclusion of the family circle, to kneel with their parents in prayer and thanksgiving.268

In the meantime what had become of Samuel? When Hamilton Edmondson was seeking to locate his sisters and brothers in desirable homes in New Orleans, he first saw Mr. Horace Cammack, a prosperous cotton merchant, whose friendship and respect he had long since won and who, upon the further representation of Samuel's proficiency as a butler, agreed to purchase him. In this wise, it came to pass that Samuel was duly installed as upper houseman in the Cammack home. Although situated more happily than most slaves he was fully determined, as ever, that the world should one day know and respect him as a free man, and patiently waited and watched for the opportunity to accomplish his purpose.

Meanwhile another element had thrust itself into the equation and must be reckoned with in the solution of the problem of his after life. It happened that Mrs. Cammack, a lady of much beauty and refinement of manner, had in her employ as maid, a young girl of not more than eighteen years named Delia Taylor. She was tall, graceful and winsome, of the clear mulatto type, and through long service in close contact with her mistress, had acquired that refinement and culture, which elicit the admiration and delight of those in like station and inspire a feeling much akin to reverence in those more lowly placed. With some difficulty Samuel approached her with a proposal and, although at first refused, finally won her as his bride.

Matters now moved along on pleasant lines for Samuel and Delia during several months, but with the advent of Master Tom, Cammack's son who had been away to college, there was encountered an element of discord, which was for a while to destroy their happiness. This young gentleman took a violent dislike to Samuel from the very first meal the latter served him. They finally clashed and Samuel had to run away. His master, however, sent his would-be-oppressor with the rest of the family to the country and ordered Samuel to return home. This he did and immediately entered upon his duties.

The year following, Mr. Cammack went to Europe on cotton business and not long after his arrival was killed in a violent storm while yachting with friends off the coast of Norway. After this event, affairs in the life of Samuel gradually approached a crisis, while in the meantime an additional responsibility had been added to himself and Delia in the person of a little boy, whom they named David.

Master Tom, being now the head of the house, left little room for doubt as to the authority he had inherited and proceeded to evince the same in no uncertain way, especially towards those against whom he held a grievance. To get rid of Samuel was first in order. This was the easiest possible matter, for there was not a wealthy family on the visiting list of the Cammacks who would not, even at some sacrifice, make a place for him in their service. Through the close intimacy of Mrs. Cammack and Mrs. Slidell, the latter was given the refusal and Samuel told to go around and see his future Mistress. To her he expressed a desire to serve in her employ but he was now determined more than ever that his next master should be himself. Accordingly he proceeded directly to a friend from whom he purchased a set of free-papers, which had been made out and sold him by a white man. These required that he should start immediately up the river but upon a full consideration of the matter he decided that the risks were too great in that direction. The problem was a serious one. An error of judgment, a step in the wrong direction, would not only be a serious, if not fatal blow to his hopes, but might lead to untold hardships to others most dear to him.

Somewhat irresolutely he turned his steps towards the river front, gazing with longing eyes at the stretch of water, the many ships in harbor, some entering, others steaming away or being towed out to open water. The thought that in this direction, beyond the wide seas, lay his refuge and ultimate hope came to him with so much force as to cause him to reel like one on whom a severe blow had been dealt. He stood for some time, seemingly bewildered, in the din and noise of the wharf, noting abstractedly the many bales of cotton, as truck after truck-load was rushed aboard an outward bound steamer. The bales seemed to fascinate him completely. A stevedore yelled at him to move out of the way and aroused him into action, but in that interval an idea which seemed to offer a possible means of escape had been evolved. He would impersonate a merchant from the West Indies in search of a missing bale of goods and endeavor to get passage to the Islands, where he well knew the flag of free England was abundant guarantee for his protection. The main thought seemed a happy one, for he soon found a merchantman that was to clear that night for Jamaica. It was not a passenger vessel, but the captain, a good-natured Briton, said that he had an extra bunk in the cabin and if the gentleman did not mind roughing it, he would be glad to have his company. The first step towards his freedom was successfully taken, the money paid down for the passage and with the injunction from the captain to be aboard by nine o'clock he returned ashore.

Only a few hours now remained to him, before a long, perhaps a lasting separation from his dear wife and baby, and thinking to pass these with them he hurried thence by the most unfrequented route, but had hardly crossed the threshold when Delia, weeping bitterly, implored him to make good his escape, as Master Tom had already sent the officers to look for him. With a last, fond embrace and a tear, which, falling upon that cradled babe, meant present sorrow, but no less future hope, the husband and father made his way under the friendly shadows of the night, back to the waiting ship.

When the officer from the custom house came aboard to inspect the ship's papers Samuel was resting, apparently without concern, in the upper bunk of the little cabin.

The captain seated himself at the center table, opposite the officer, and spread the papers before him. "Heigho, I see you have a passenger this trip," and then read from the sheet: "Samuel Edmondson, Jamaica, W.I., thirty years old. General Merchant."

"Yes," said the captain as he concluded. "Mr. Edmondson asked for passage at the last moment and as he was alone and we had a bunk not in service, I thought I'd take him along. He has a valuable bale of goods astray, probably at Jamaica, and is anxious to return and look it up."

"Well I hope he may find it. Where is he? let's have a look at him."

"Mr. Edmondson, will you come this way a moment?" called the captain.

As may be imagined the subject of this conversation had been listening intently and now when it was demanded that he present himself, he murmured a fervent "God help me" and jumped nimbly to the deck.

"This is my passenger," said the Captain, and to Samuel he said: "The customs officer simply wished to see you, Mr. Edmondson."

Samuel bowed and stood at ease, resting one hand upon the table and in this attitude without the quiver of an eyelash or the flinching of a muscle, bore the searching look of the officer, which rested first upon his face and then upon his hand. The flush of excitement still mounting his cheek and brow, gave a bronzed swarthiness and decidedly un-American cast to his rich brown color, while his features, clean-cut and but slightly of the Negro type, with hands well shaped and nails quite clean, were a combination of conditions rarely met in the average slave. The first glance of suspicion was almost immediately lost to view in the smile of friendly greeting with which the officer's hand was extended. "I hope you may recover your goods," were the words he said and, rising, added: "I must be off." The captain had meanwhile placed his liquor chest on the table and, in a glass of good old Jamaica rum, a hearty "Bon voyage" and responsive "Good wishes" were exchanged.

The subsequent story of Samuel, interesting and adventurous as it is, scarcely comes within the scope of the purpose of this article. After a brief stay at Jamaica, Samuel sailed before the mast on an English schooner carrying a cargo of dye-wood to Liverpool. Two years were passed here in the service of a wealthy merchant, whom he had served while a guest of his former master in New Orleans. During the third year he was joined by his wife and boy who had been liberated by their mistress. Subsequently the family took passage for Australia under the protection of a relative of his Liverpool employer, who was returning to extensive mining and sheep-raising interests near the rapidly growing city of Melbourne.269

John H. Paynter, A.M.The Edmonsons

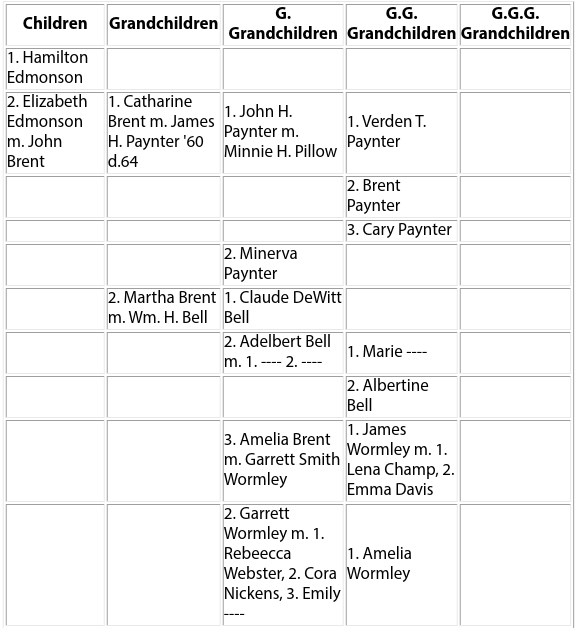

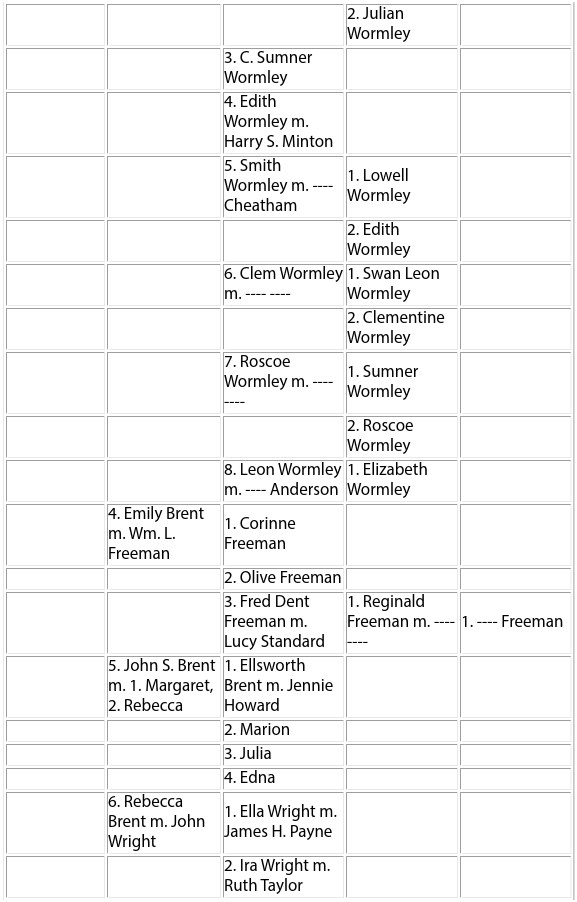

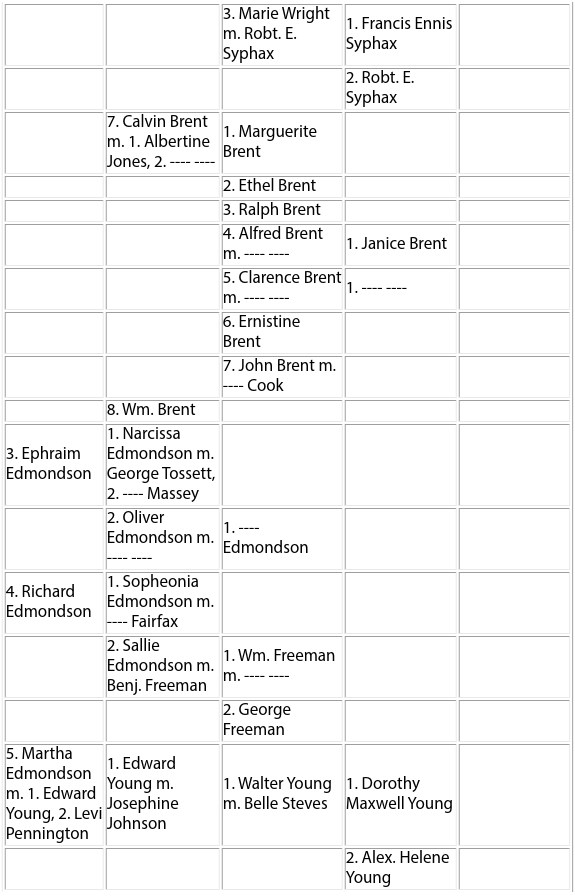

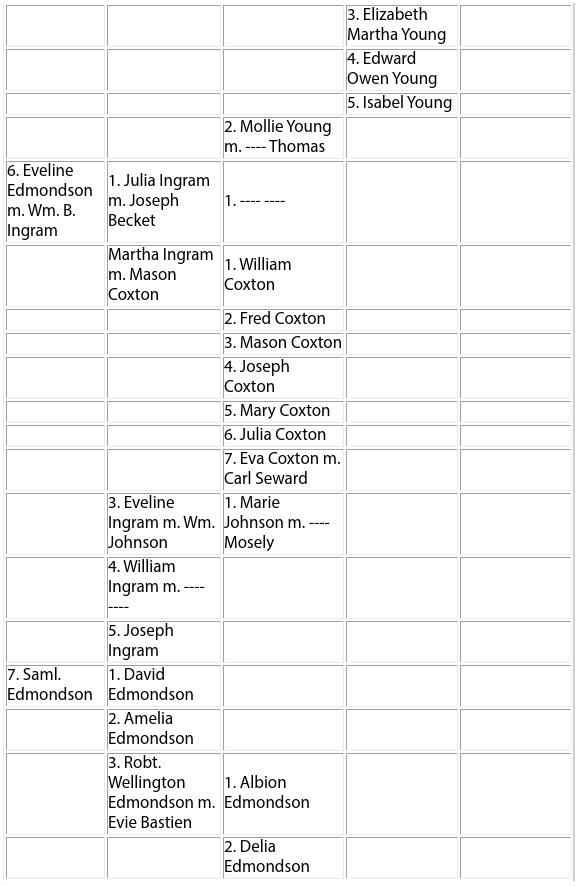

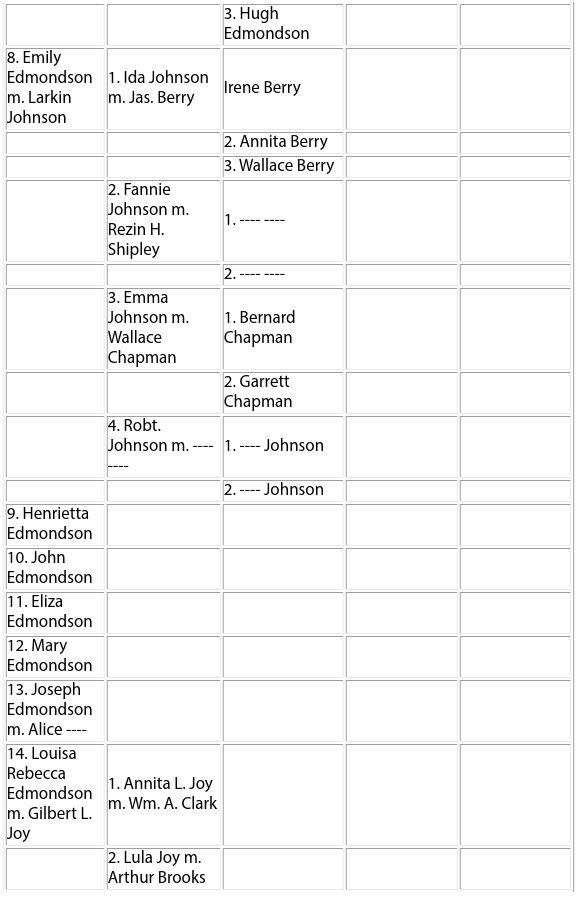

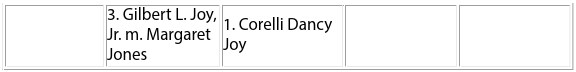

Descendants of Paul and Amelia Edmondson

Lorenzo Dow 270

This is the record of a remarkable and eccentric white man who devoted himself to a life of singular labor and self-denial. In any consideration of the South one could not avoid giving at least passing notice to Lorenzo Dow as the foremost itinerant preacher of his time, as the first Protestant who expounded the gospel in Alabama and Mississippi, and as a reformer who, at the very moment when cotton was beginning to be supreme, presumed to tell the South that slavery was wrong.

He arrests attention–this gaunt, restless preacher. With his long hair, his flowing beard, his harsh voice, and his wild gesticulation, he was so rude and unkempt as to startle all conservative hearers. Said one of his opponents: "His manners (are) clownish in the extreme; his habit and appearance more filthy than a savage Indian, his public discourses a mere rhapsody, the substance often an insult upon the gospel." Said another as to his preaching in Richmond: "Mr. Dow's clownish manners, his heterodox and schismatic proceedings, and his reflections against the Methodist Episcopal Church, in a late production of his on church government, are impositions on common sense, and furnish the principal reasons why he will be discountenanced by the Methodists."

But he was made in the mould of heroes. In his lifetime he traveled not less than two hundred thousand miles, preaching to more people than any other man of his time. He went from New England to the extremities of the Union in the West again and again. Several times he went to Canada, once to the West Indies, and three times to England, everywhere drawing great crowds about him. Friend of the oppressed, he knew no path but that of duty. Evangel to the pioneer, he again and again left the haunts of men to seek the western wilderness. Conversant with the Scriptures, intolerant of wrong, witty and brilliant, he assembled his hearers by the thousands. What can account for so unusual a character? What were the motives that prompted this man to so extraordinary and laborious a life?

Lorenzo Dow was born October 16, 1777, in Coventry, Tolland County, Connecticut. When not yet four years old, he tells us, one day while at play he "suddenly fell into a muse about God and those places called heaven and hell." Once he killed a bird and was horrified for days at the act. Later he won a lottery prize of nine shillings and experienced untold remorse. An illness at the age of twelve gave him the shortness of breath from which he suffered more and more throughout his life. About this time he dreamed that the Prophet Nathan came to him and told him that he would live only until he was two-and-twenty. When thirteen he had another dream, this time of an old man, John Wesley, who showed to him the beauties of heaven and held out the promise that he would win if he was faithful to the end. A few years afterwards came to the town Hope Hull, preaching "This is a faithful saying, and worthy of all acceptation, that Christ Jesus came into the world to save sinners"; and Lorenzo said: "I thought he told me all that ever I did." The next day the future evangelist was converted.