Полная версия

The Life and Legacy of Saint Patrick: Mission, Trials, and Enduring Influence

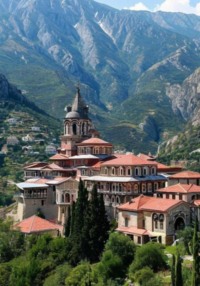

Today, visitors to Lérins might see only a few weathered stones, remnants of the cells and chapels where monks once sought solitude. But in Patrick’s day, this quiet island cloister held a magnetic attraction for men worn down by the storms of worldly life or those desiring uninterrupted communion with God. Its remoteness—“withdrawn into the great sea,” as contemporaries described it—made it a refuge for the spiritually shipwrecked, a place where one could “vacare et videre,” to be free for prayer and insight.

It was to this monastery that Patrick came after his escape from slavery. For the first time, we can place him in a definite location where he likely lived and worked for a number of years. The details of his admission are unknown, but his own reflections on his state of mind suggest how deeply he must have been drawn by the ascetic and religious ideals embodied by the community. After the trauma of captivity and the hardships of wandering, the monastic life would have offered a healing structure—discipline, prayer, and fellowship—that could restore his spirit and nurture his faith.

The monastery was home to several men of notable influence who would later shape the church in Gaul and beyond. Among these were Hilary, who became Bishop of Arelate (modern Arles); Maximus, the second abbot of Lérins who later rose to be Bishop of Reii; Lupus, future Bishop of Trecasses; Vincentius, a teacher and writer within the cloister; and Eucherius, who composed theological works and lived with his wife Galla in a hermit’s cell on the nearby larger island of Lero. The communal life at Lérins was not only one of ascetic discipline but also of intellectual and spiritual endeavor. The anecdote about Honoratus sending a letter on a wax tablet to Eucherius—who responded that the abbot had restored sweetness to the wax—reflects the gentle camaraderie and sharp wit among these early monks.

The monastic ideal, as it flourished at Lérins, attracted many who sought to transcend the passions and distractions of the world, hoping to “break through the wall of the passions and ascend by violence to the kingdom of heaven,” as one monk put it. Among these aspirants was Faustus, a fellow countryman of Patrick’s. Although it is uncertain whether Faustus was present during Patrick’s stay or arrived later, he was certainly one of the prominent figures associated with Lérins. Faustus was a man of greater scholarly refinement than Patrick, educated in the classics of ancient philosophy and skilled in literary style. He would later correspond with Sidonius Apollinaris, the celebrated poet and statesman of the fifth century. While Faustus’s name has faded into obscurity, Patrick’s legacy would become monumental, his name revered across Christian households in the West and far beyond.

The years Patrick spent at Lérins left an indelible mark on his religious vision. Immersed in the monastic ideal, he grew convinced of the value of a disciplined, prayerful life, yet his destiny was not to be one of withdrawal but of engagement. Monastic communities, he came to believe, were not just retreats but vital elements in the structure of the Christian Church and its mission. Though during this period he likely did not yet conceive of returning to evangelize Ireland, the seeds of his future calling were being sown. The hardships of his past had convinced him that he had been held “in the hollow of God’s hand” during his captivity, and his youth’s earlier ambitions were tempered by experience and spiritual reflection.

At Lérins, Patrick may have initially hoped to remain a monk indefinitely—“to come to the desert is the highest perfection.” But within him, a deeper urge for action was stirring. After several years of monastic discipline, he left the island cloister and returned to Britain, where the unfolding purpose of his life became clearer.

Back in Britain, Patrick was welcomed warmly by his kinsfolk, who embraced him “as a son” and implored him not to depart again. Yet even amidst their affection and pleas, Patrick’s inner conviction had crystallized. A powerful vision in the night revealed the path he was to follow. In this dream, a man named Victoricus appeared, a figure probably known to Patrick from Gaul, holding a bundle of letters. One letter bore the “voice of the Irish,” a plea that stirred Patrick’s heart. The cry came from near the wood of Fochlad by the western sea, beseeching him to return and “again walk amongst us as before.” This dream pierced Patrick’s soul, awakening a profound sense of mission and compassion.

Later traditions added emotional layers to the story, suggesting that the cry came from the unborn children of Ireland, emphasizing the spiritual urgency of the unbaptized souls’ plight. Although Patrick himself did not mention this, the tradition captures the deep sympathy and religious urgency that drove his mission. It highlights the Church’s doctrine at the time—that unbaptized infants faced eternal punishment—and the heavy burden this placed on the conscience of devout Christians like Patrick.

This spiritual resolve was intertwined with the great theological controversies of the day, particularly the debate sparked by Pelagius, a figure of Irish or Irish-British descent whose teachings challenged fundamental Church doctrines. Pelagius argued for the inherent freedom of the human will, denying original sin and the necessity of infant baptism for salvation. His ideas spread widely and provoked intense opposition, especially from Augustine of Hippo. The Pelagian controversy was not merely theological hair-splitting; it touched on profound questions about human nature, morality, and salvation that still resonate today.

Patrick, living in this intellectual and spiritual climate, would have been deeply aware of the stakes. The harsh doctrine that condemned the unbaptized to hell would have made the fate of the Irish people—a land still largely pagan—a matter of urgent concern for him.

Despite his profound calling, Patrick initially struggled with doubt. He questioned his own readiness, lamenting his lack of formal education and fearing the dangers of returning to the land of his captivity. Yet the inner voice—the divine compulsion he described as an external intelligence—strengthened his resolve. This kind of mystical certainty, common in the hagiographies of saints, marked the turning point in Patrick’s life, transforming his hesitation into mission.

With his purpose fixed, Patrick journeyed back to Gaul, where he sought preparation for his great task. He understood that success would require more than personal zeal; it demanded theological education, ecclesiastical endorsement, and material support. He chose to study at Auxerre, a town on the Yonne River known for its vibrant Christian community led by the respected Bishop Amator. Auxerre had become a center for theological study, and Patrick likely came into contact with British ecclesiastics who had links with Gaul. It is also possible that Auxerre’s known interest in the Irish Christian communities influenced his decision.

At Auxerre, Patrick was ordained deacon by Bishop Amator, alongside two other young men who would later assist in the Irish mission: Iserninus, an Irishman originally named Fith, and Auxilius (Ausaille), whose origins are uncertain. These ordinations marked the formal beginning of a concerted effort to organize the Christianization of Ireland.

Yet Patrick’s journey toward his mission was long. At least fourteen years elapsed between his ordination and his departure for Ireland. This delay was not due simply to training but to resistance from ecclesiastical authorities who viewed his plans with skepticism. His rustic background and perceived lack of education were cited against him. These obstacles reveal the challenges faced by early missionaries who were often dismissed as unqualified or visionary fanatics.

During these years, another figure important to Patrick’s mission emerged: Bishop Germanus of Auxerre, Amator’s successor. Germanus was a former lay official who had embraced the Church, known for his leadership and holiness. In 429, Germanus undertook a mission to Britain to combat Pelagianism, which was causing turmoil among the British Christians. His mission, backed by Pope Celestine and assisted by the deacon Palladius, was successful in suppressing the heresy temporarily.

Palladius himself played a crucial role in early Irish Christianity. Shortly after Germanus’s mission, Palladius was appointed bishop for the Christians in Ireland, marking the first formal recognition by the Roman Church of Irish Christian communities. This appointment likely responded to appeals from Irish Christians and may have been connected to the wider Pelagian controversy.

Thus, the intertwined struggles over doctrine and missionary activity reveal a vibrant network linking Britain, Gaul, and Ireland during this tumultuous period. The Pelagian controversy catalyzed ecclesiastical action, shaping the context in which Patrick prepared and eventually undertook his mission.

Fully equipped by years of study, prayer, and support from influential Church leaders, Patrick was finally ready to embark on the task that would transform the religious landscape of Ireland. His journey from captivity to monastic retreat, from doubt to divine commission, and from rustic youth to ordained deacon and missionary marks one of the most remarkable spiritual transformations of late antiquity.

* * *

The Early Irish Church and the Missions of Palladius and Patrick: Foundations of Christianity in Ireland

The origins of the Christian Church in Ireland are best understood against the backdrop of broader ecclesiastical and political developments in late antiquity, particularly in Britain and Gaul. Patrick’s own autobiographical narrative hints at complex relationships and conflicts, including the betrayal of a trusted friend—an ecclesiastic, probably from Britain or Gaul—who had once been a close confidant. Patrick entrusted this friend not only with his deepest plans but even with his soul, as the phrase credidi etiam animam suggests, underscoring the intensity of their bond and the trust involved. This friend had encouraged Patrick’s aspirations, especially his desire to serve as a bishop in Ireland, advocating fervently for his elevation when the opportunity arose. The discussions around appointing a bishop for Ireland took place in Britain, even though Patrick himself was absent, revealing a web of ecclesiastical diplomacy and maneuvering beyond the island itself. This context aligns closely with the historical moment in A.D. 429, when Germanus of Auxerre came to Britain to combat Pelagian heresy—a doctrine threatening to fracture Christian unity. If Pelagianism had also penetrated Ireland, it would have posed a threat not only locally but to the churches in Britain, given their proximity and shared concerns. It is reasonable to speculate that Irish Christian representatives may have sought Germanus’s intervention, prompting discussions about appointing a bishop capable of combating heresy and guiding the Irish Christian communities toward orthodoxy. It is within this milieu that Patrick’s friend likely proposed him as the candidate best suited for the role.

For Patrick, the long-awaited moment to realize his missionary ambitions seemed finally within reach. Interest in Irish Christianity had probably been growing quietly in Gaul, especially around Auxerre where Germanus held influence. Now, the matter reached the highest ecclesiastical authority, Pope Celestine I, signaling the prospect of official sanction and practical support. Despite Patrick’s hopes and his advocates’ efforts, Celestine appointed another figure to the bishopric of Ireland: the deacon Palladius. Consecrated in 431, Palladius was a man of proven ability in confronting Pelagianism in Britain, likely accompanying Germanus during his campaigns. Celestine’s choice was motivated by a pragmatic concern: the spiritual welfare and doctrinal purity of the already-existing Christian communities in Ireland, rather than the conversion of the pagan majority. Palladius’s mission was therefore not primarily evangelistic but aimed at safeguarding orthodoxy. Irish Christian representatives may have requested his appointment, seeking a leader experienced in theological controversies who could organize their fledgling communities effectively.

The historical record shows that Palladius’s mission in Ireland was brief and, by some accounts, unsuccessful. He is said to have arrived, labored for about a year, then departed, possibly disheartened by the challenges he faced. Afterward, he traveled to the land of the Picts in northern Britain, where he died. Yet, these traditional accounts are not definitive. It is plausible that his work among the Picts was a continuation of his ministry in Ireland, considering that Christian groups lived among the Picts of Dalaradia in northern Ireland. Tradition links Palladius’s brief mission to the Wicklow area, specifically the lands of the children of Garrchu, whose local chief was reputedly hostile to him. Despite the short duration of his stay, Palladius is credited with founding three early churches: a small prayer house possibly known as Tech na Rómán on a wooded hill near the river Avoca, symbolizing a connection with Rome; Domnach Airte near Dunlavin, the “Lord’s House of the High Field,” associated with Leinster’s royal seats; and Cell Fine, the “Church of the Tribes,” which preserved his relics and sacred items from Rome. While Palladius’s tangible impact on Irish ecclesiastical life may have been limited due to his brief tenure, his mission marked a significant milestone as the first official extension of Roman authority into Ireland. Until then, no Roman military or civil power had reached the island, and its indigenous customs remained intact, sheltered by its geographical isolation. Palladius’s arrival symbolized the beginning of Ireland’s incorporation into the wider Christian world under Roman spiritual leadership, even as the absence of imperial administration preserved native traditions, allowing Christianity to develop distinctively in the island’s unique cultural environment.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «Литрес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на Литрес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.