Полная версия

Synthesis of Architectural Form. From Meaning to Concept

Thus, a single semantic root is found that unites philosophical thought and architectural and aesthetic pursuit.

Aleksei Losev explained his idea of synthesis using examples from various fields of science – geometry, chemistry, astronomy. Synthesis is such a unity of opposites when they form a new quality without losing itself. In this place, Hegel used such words as "sublation" and "negation of negation." The antithesis negates the thesis, and synthesis negates the antithesis. But Losev since his youth was inspired for creation – the highest synthesis.

So, following Losev, we will think of synthesis not as the "negation of negation," but as creation (1), as the creation of a new (2), as the creation of a fundamentally new (3). A fundamentally new thing is born from the combination of the opposites – as different as possible, or at least from different, dissimilar, non-identical. After all, why synthesize the identical, if it is the same anyway?

The second of the principles under consideration was discovered already in the ancient philosophy. The whole is an organism in which it is impossible to replace one part with another without damage, because all parts bear the stamp of their integrity. The whole connects the parts, and each part reveals the whole, highlights its important facet.

In modern architecture, Frank Lloyd Wright came closest to this understanding: "In the realm of organic architecture human imagination must render the harsh language of structure into becomingly humane expressions of form instead of devising inanimate facades or rattling the bones of construction. Poetry of form is as necessary to great architecture as foliage is to the tree, blossoms to the plant, or flesh to the body" [46, 177]. "The word organic in architecture does not mean belonging to the animal or plant world," Wright wrote. The word "organic", according to him, means that the whole is to the part as the part is to the whole [46, 181].

An organism is the opposite of a mechanism in which the scheme prevails over the "flesh" of the parts. The architectural composition, in turn, can be organic, or combinatorially mechanistic. An organic composition is born as a sculptural integrity, a sculpture that unfolds from its grain – an idea, and not as a result of spontaneous technical manipulations that can give the impression of being spectacular.

The third principle speaks about the disclosure of the inner in the outer, about the manifestation, germination of a semantic idea into a certain form, including a material one. The form expresses the meaning, but does not encode or encrypt it. Losev's aesthetic system can be called the aesthetics of expression. In this phenomenon of the greater in the lesser, the ideal in the material, or, in Losev's synonymous terminology, the eidetic in the meonal, symbols play a key role. Since the architectural form reveals meanings in three–dimensional shells–sculptures, it is also symbolic. A symbol is a meeting point of two realities – the semantic source and expressive elements. Their unity is revealed in the diverse figurative images of works of art and other human activities.

We will discuss the expressive semantic energy in architectural morphogenesis in a separate chapter below.

The author does not pretend to be exhaustive in covering the meaning-generating potentials of Losev's philosophy for the tasks of architectural composition, and considers all the proposed work to be a full-fledged beginning that can open up into something more, and hopes that the given vector will resonate with architects, educators and thinkers who develop the philosophy of creativity for applied purposes.

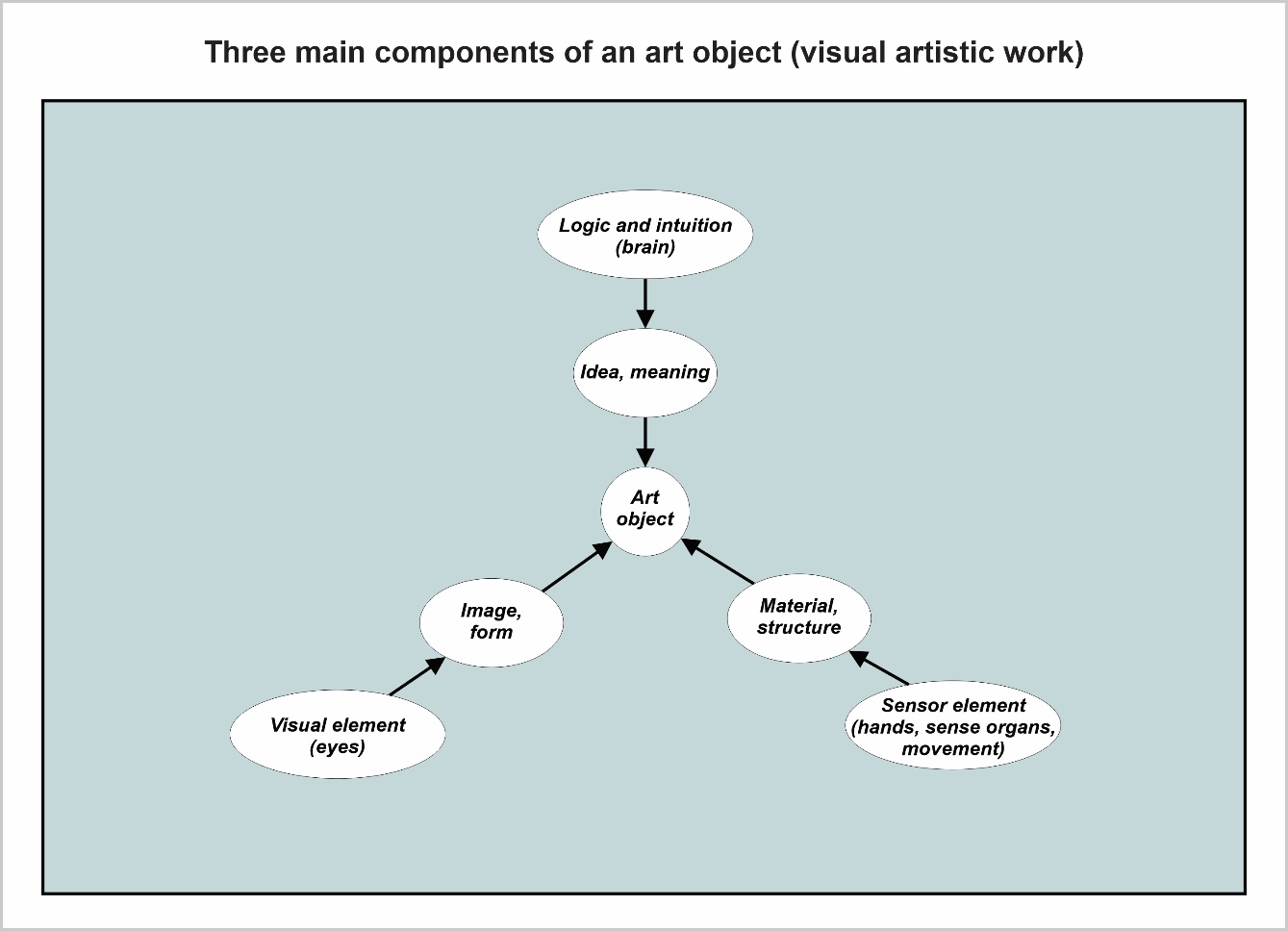

The Three Forces That Create an Art Object

A work of art is born at the intersection of three forces: this is a visual, sensory and logical principle. The role of sensory and visual principles is well known. The effect of the verbal and logical, ideal and semantic component is less obvious. Thus, A. G. Rappaport notes: "Perhaps it is precisely the lack of experience in the logical study of professional thinking that has led to the fact that it has become customary that verbal forms of thought are underestimated and thinking in images is set in opposition to them" [67]. Next, we will try to substantiate the importance of the word and conceptual logic in architectural form generation – it is no less than the importance of three–dimensional images as such and materials / structures.

The Basis of the Method Is a Dialectical Triad, a Synthesis

When we think of modern architecture, we are in two minds: from the edge that it can do anything (conquer gravity and explore other planets) to the edge that it is a thing of the past, when one can hear that "there is no longer a recognized formal concept", but there is a "chimerical consciousness", and "it cannot create a form, it does not believe in it" [68]. We can say that the destiny (as the path, not the fate) of architecture is the destiny of form. Architecture exists as long as there is a form and there is a will to create a form, and architecture degenerates into something else (for example, a mirror or a screen) when the concept of the form is devalued, ceases to be a worthy task, and is replaced by a game or imitation.

Two forces inspired the author to propose a discussion to dear readers – the love of architecture and the philosophy of Aleksei Fyodorovich Losev. The thoughts outlined here run the risk, in the words of Grigory Revzin, of remaining marginal "both in relation to architectural studies, which are not engaged in philosophy, and in relation to philosophy, which is not interested in architectural studies [italics mine Yu.P.]" [29, 7].

But there is a third area for which the thoughts of this book were honed – pedagogy: pre-university training of students – future designers and architects, and teaching architectural composition (propaedeutics) to first-year students of architectural design colleges and universities. The ultimate goal of this work is of an applied nature: it is intended to introduce form-generating architectural composition into the practice of teaching creative art.

N. F. Metlenkov draws attention to the fact that "creativity as a philosophical and psychological concept has not found a place in logic. Therefore, the theory of teaching creativity has not been worked out either. Project creativity is still taught in artisanal manner, only in the process of joint project activity of the teacher and the student" [35, 427]. The material of the proposed essays seeks to fill this gap and form a theoretical core for the application of the constructive dialectical method in architectural propaedeutics and at the design stage aimed at the compositional and artistic solution of the image of the future building.

The practical results of applying our method – selected works of the author and his students – are experimental in a positive sense of the word. According to A.P. Kudryavtsev, "it is necessary to look for all the latest methodological tools; there is no other way to new methodological tools except the path of experimentation; without experimentation, one cannot be in pedagogy today, that's why one must experiment, and experiment very actively, in all areas of architectural education" [36, 369].

In the context of the polemic of "formalists" and "functionalistic constructivists", the author's thoughts are more formal in nature and belong to the field of artistic form generation. Formalism as a phenomenon is rehabilitated in the works of S. O. Khan–Magomedov [25] and the ideas of Zaha Hadid's colleague Patrick Schumacher [48]. Formalism is harmful if it is the only approach, but it is fruitful to develop it as a significant part of an integrated design method..

Before proceeding to the main thoughts, let us clarify that the established connection between philosophical concepts and architectural categories belong mainly to categorical dialectics – one of the foundations of A. F. Losev's thinking. A. F. Losev's philosophy itself is broader, and represents a complex synthesis of dialectics, phenomenology, and other important structural and logical elements. It is his thoughts and works that the author refers to as the most familiar to him.

Revealing the understanding of the cosmos and space among the Greek philosophers, Aleksei Fyodorovich Losev wrote about its heterogeneity4, and on the one hand, contrasted it with "Newton's space"5, on the other – connected it with "Einstein's space". For modern physics, the vacuum turned out to be not an absolute void, but a medium with a generative force [71]. According to V. V. Rozanov, space contains the full potential of various forms: "… in every place of space there is a form of each given object; and, moving, it does not move its form with it <…>, but, having left it and thereby having made it potential again, it enters into a new form, identical to the previous one in appearance, but located in a different place in space – exactly in the place where it moved to. Thus, the apparent movement of a form is essentially a continuous concealment and detection of visible spatial forms along the path of a moving substance – concealment and detection accompanying the exit and entry of this substance from one form into another; so that the substance moves, but the forms remain motionless" [17, 162-163]. Space is the actual and potential repository of the whole infinity of all possible forms. With this understanding, the architect, creating a new form, actualizes the potency already contained in the space. It is important here to dwell on the idea that this infinity includes both harmonious and disharmonious forms. Similarly, musical instruments, such as the piano keyboard, contain the full potential of sounds, both euphonious and cacophonous.

New experiences in architectural morphogenesis are numerous, radical, and expanded to include the aesthetics of the ugly. The "lack of freedom" of a new level – dependence on technology – is one of the main reasons for the triumph of the ugly in twentieth-century art"6 (Bychkov V. V.). Reflecting on the role of computer modeling in creative searches, Alexander Ryabushin warned: "Today, "the computer allows you to try everything without building at all"… However, there are objective reasons for concern: each tool generates specific dependencies (and the more sophisticated it is, the stronger it is), and the identical programs from Silicon Valley can lead to an excessive convergence of the things that, by their very nature, should have originality, even in our [architectural – Yu.P.] field. The universality of streamlined whale-like outlines, suspiciously reminiscent of newfangled sports sneakers in their sleekness, is already beginning to confuse [33, 52]. If in the case of the resemblance to sneakers we can talk about an obsessive trend in the morphogenesis, then in the case of the aesthetics of forms resembling insects or internal organs7, it's time to recall the "Pandora's box". As I. A. Dobritsyna notes, "the non-linear logic of a computer has made it possible to build models of complex objects.… Gilles Deleuze turned out to be the closest of all other philosophers to non-linear science.… It is known that in his last works he already expressed concern about experiences of non-linear thinking, trying to propose ways out of the fascinating, but unusual and demonically uncomfortable world of non-linearity [italics mine Yu.P.]" [39, 9].

The most important antidotes to such inhumane aesthetics are the memory of the emotional and spiritual well-being of people in the designed and created new environment; the preservation of the art of live creative freehand drawing; the maintenance of classical ideals of beauty, proportion, harmony, integrity, which does not imply the impossibility of developing new architectural forms.

Before outlining an alternative aesthetic in its comparison with parametric and blob aesthetics, let's turn to the basic principles of architecture.

We encounter architecture as an art that has a direct and most complete communication with space. "Space, not stone, is the material of architecture," Nikolai Ladovsky formulated for centuries [25, 65-67]. Architecture, of course, acts as a repository for man and his activities [2, 122-123]. At the same time, while forming the space, architecture is revealed externally, and therefore it is an eidetic form, which means it has its own figurative face, image, and, in this sense, it is connected with a sculptural form, as N. Ladovsky convincingly argued: "Although space appears in all forms of art, only architecture makes it possible to read the space correctly. Structure is included in architecture insofar as it defines the concept of space. The basic principle of the designer is to invest a minimum of material and get maximum results. It has nothing to do with art and can only accidentally satisfy the requirements of architecture. Since architecture deals with space, and sculpture deals with form, it is best to design the building as a sculpture from the outside and as architecture from the inside, the thickness of the walls does not matter. With this approach to design, the exterior does not always express the internal content [italics mine Yu.P.]" [25, 67].

A. F. Losev often uses the word "statueness" as a synonym for sculptural art. It sends us back us to the entire ancient Greek statues with their reference qualities of fine proportions, measure, unexalted expression, clarity, balance and harmonious movement. The same features are characteristic of ancient Greek philosophy and architecture. Losev's thought inherited these qualities of measure, structure, integrity, and mobility from the ancient cosmos. It is these qualities that reveal the architectural form as beautiful and noble.

It can be said that sculpture is an organically inherent quality of many architectural works in their centuries-long development, from the Egyptian pyramids to the modernism of K. Melnikov and A. Aalto. The turn of the 20–21 centuries, marked by the rapid development of computer modeling, was the beginning of a fundamentally new architectural aesthetic.

The followers of modern Western architectural thought are characterized by pedaling the binary scheme of their new look and classical and modernist architectural paradigms, which are now combined into one type. Thus, the philosopher and mathematician of the early 20th century Alfred North Whitehead argued that "Process, not substance, is the fundamental characteristic of reality" [45, 88]. In the semantic field of Aleksei Fyodorovich Losev, such a "clash" of opposites is perceived as a commitment to formal logic that shall be overcome on the path of dialectical logic: One, Being, Becoming… There is no opposition of "what" and "how", but rather their transition into synthesis (Becoming and Having Become). This is a synthesizing thought, not an opposing one; a thought that has the intuition of unitotality as its inner message (Vl. Solovyov) and the higher synthesis of happiness and knowledge (A. Losev).

The concepts of symbiosis and alliance are similar in meaning to the category of synthesis in modern theoretical thought. So, Jeffrey Kipnis outlines a synthetic direction: "Folding" is a strategy for creating "smooth mixtures", according to which something fundamentally new can be created from two or more qualitatively different types of structural organization. For example, a homogeneous modernist "grid" can enter into a symbiotic connection with a hierarchically ordered structure" [41, 602-603].

A radically contrasting position was taken by Patrik Schumacher in the Parametricist Manifesto [69], who formulates opposition to modernism as taboo: "Avoid rigid geometric primitives like squares, triangles and circles, avoid simple repetition of elements, avoid juxtaposition of unrelated elements or systems… We might think of liquids in motion, structured by radiating waves, laminal flows, and spiraling eddies… There are no platonic, discrete figures or zones with sharp outlines" [69].

The modernist type of forms, and with it the entire ancient type of form perception, is declared obsolete, discrete, and rigidly regular. Turning to Losev's thought, we see that the ancient understanding is much deeper than such a parametric reduction of Antiquity to a single Euclidean type. A. F. Losev expressed the idea of the heterogeneity of space most fully in his work "The Ancient Cosmos and Modern Science": "Space has varying degrees of tension and is completely heterogeneous. Only metaphysical prejudices and blind dogma could make us believe for centuries that space had an absolute character. Space is just as compressible and expandable as a physical thing in a commonly understood space. Here, it is not the qualities of absolute space that are heterogeneous, but space itself is devoid of absoluteness and is relative everywhere, i.e., it depends on various other conditions" [1, 226].

If in understanding the heterogeneity of space it is possible to find a common point between the ancient cosmos and parametericism, then the concept of "seamless" takes us away from "sculptural" and "figurative" in the opposite direction from the classical understanding. This is "a new type of form that has absorbed all the dynamics of its own generation, tending to a kind of "formlessness", to absolute freedom" [41, 601]. The juxtaposition of such concepts as architectural form and "formlessness" sounds paradoxical. Not without irony, A. F. Losev wrote: "A pile of sand, they say, is shapeless. But, of course, this formlessness is only relative here, that is, we are talking about it only when comparing this pile with other objects. In the absolute sense of the word, a pile of sand also has its own distinct shape, namely the shape of a pile. The clouds in the sky are also shapeless. And again, this should be understood only relatively" [7, 68]. Protozoa is the bionic form that is most closely related to "seamless" searches. And the icons for gadgets also paradoxically bring us back to an earlier moment of the birth of writing, when letters were just beginning to form as hieroglyphic signs.

Let's summarize our comparison in a table of key concepts:

P. Schumacher speaks of a "seamless fluidity akin to natural systems." There is a fundamental difference in how an architectural form correlates with nature. If parametricism and bionics in many of their searches follow the path of maximum similarity and, in fact, literal copying and non–symbolic reproduction of biological forms in their external fluidity and curvilinear complexity, and sometimes a certain kind of invertebrate forms, then Antiquity is characterized by a symbolic vision. The symbol does not necessarily strictly resemble the prototype, the symbol may be different, but at the same time represent the prototype. A symbol is a manifestation of one, which is hierarchically greater, in the other, hierarchically smaller. Thus, the Greek peripter has no literal counterpart in nature, and at the same time it represents an ordered cosmos. It symbolically depicts the universe, outwardly having a philosophically different form.

Moving away from the binary scheme of "primitive classical and modernist form" – "flowing seamless intricate complex parametric form", in the following discussion we will outline an exit to the aesthetics of a dialectically organized form combining classically clear forms and modern complex geometry, without "entanglement", which is uncomfortable for a person's psychological sense of self8, and depressing similarities with certain types of biological forms (such as forms of insects, invertebrates, internal organs, arteries, etc.)

The symbol expresses, reveals the prototype. In the word "revealing", one can feel the shape of a ray: it is a ray of light passing through other medium. In "folding", one can see a bend. A "fold" is a logical figure that brings a certain variety to a conditional uniformity. Discrete elements are absorbed by it, merged into continuity. "The "fold" does not tolerate gaps" [41, 600].

Here we can recall the antinomies of Father Pavel Florensky – examples of precisely thought gaps. The first such gap is the ontological difference between the Creator and creature in theism. In this context, the concepts of "seamless" and "fluid", which do not tolerate discontinuities, correlate with pantheism, for which being is both the cosmos and the absolute, which are consubstantially generating each other. The symbol is present, when there is an ontological abyss between the Creator and created world with a completely different nature.

Meaning can be expressed in words, sounds, forms, etc. The leading meaningful role in A. F. Losev's philosophy is given to the word. It originates in the Gospel of John and patristic thought. St. Gregory of Nyssa emphasized that man is a verbal being9. Hence, let's formulate the fundamental principle of the updated architectural propaedeutics: The word has a leading role, and it has generative power. Since any architectural form is not only perceived by the senses, but also described in words and concepts, it is inextricably linked with them in our perception. While reflecting over architectural forms, the word can come not only afterwards as an architectural and art criticism discourse, and not only be "parallel" to the design process, but also be the primary source of architectural creativity. The author has pedagogical experience in applying this approach that has shown good results in revealing the creative architectural imagination of schoolchildren and students. And here we fundamentally disagree with the idea of the "secondariness" of the word for the architectural development of children, expressed by D.L. Melodinsky: "Decisive importance should be given to the development of spatial imagination and thinking. This form of thinking, different from the abstract one, is capable of conjuring up images in the mind, manipulating them without words [italics mine Yu.P.], and seeing a special language in the spatial characteristics of the objective world of forms that carries the meanings contained in them" [42, 220]. We see the danger of modern visual culture, which today's children grow up on, precisely in its "wordlessness, unverbal character", its desire to be autonomous from verbal thinking and "manipulate images without words."

A. F. Losev's philosophy reveals a dialectical type of thought, different from formal logic and binary schematism. The key concepts in our discussion are the dialectical triad and synthesis. In its most simplified form, the dialectical triad manifests itself as a thesis, antithesis and synthesis [7, 116]. Thesis and antithesis are any two opposite concepts, their opposition is overcome in synthesis. Dialectics requires that "two opposites, despite their substantial specificity and independence, merge in a synthesis, where it is no longer possible to distinguish these two opposites. The synthesis represents a completely new and original quality, but it nevertheless, remains a condition for the possibility of emergence of the two original opposites from it" [9, 56]. Synthesis becomes such a union of two opposite principles, in which they do not only lose themselves, but also acquire a new quality, unknown to them before synthesis: "the whole is such that, although it consists of parts, it does not reduce to these parts at all, but there is some new quality, thanks to which separate, mutually isolated things turn into just certain parts of just the certain whole. In other words, obtaining a new quality from two other qualities that have nothing in common is simply the result of the dialectical unity of opposites" [7, 331].

A. F. Losev's concept of the whole as a synthesis of its parts is close to Father Pavel Florensky's concept of the form: "The concept of the whole, "which is prior to its parts," and which, therefore, determines the composition of its elements. And this is the form" [15, 18]. Summarizing, we can say that the whole is a singularity presented as a synthesis of its parts and properties, irreducible to their sum, and manifested in a form (eidetic image). In the Losev semantic field, "self-identical difference", "coordinated separateness", and "single separable integrity" are similar concepts. In composition, it is necessary to give the separateness of forms, and to give their unity, and to coordinate their separateness and their unity as one whole.