полная версия

полная версияBlackwood's Edinburgh Magazine — Volume 53, No. 331, May, 1843

This revision of her fiscal system, and reconstruction, on fair and reciprocal conditions, of her commercial code, are questions of far deeper import—and they are of vital import—to Spain than to this empire. Look at the following statement of her gigantic debt, upon which, beyond some three or four hundred thousand pounds annually, for the present, on the capitalized coupons of over-due interest accruing on the conversion and consolidation operation of 1834, the Toreno abomination, not one sueldo of interest is now paying, has been paid for years, or can be paid for years to come, and then only as industry furnishes the means by extended trade, and more abundant customhouse revenues, resulting from an improved tariff.

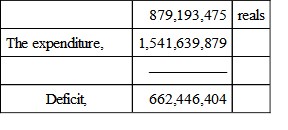

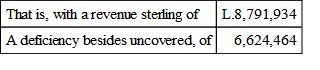

The latest account of Spanish finance, that for 1842 before referred to, exhibits an almost equally hopeless prospect of annual deficit, as between revenue and expenditure; 1st, the actual receipts of revenue being stated at

Assuming the amount of the contraband traffic in Spain at six millions sterling per annum, instead of the ten millions estimated, we think most erroneously, by Señor Marliani, the result of an average duty on the amount of 25 per cent, would produce to the treasury L.1,500,000 per annum; and more in proportion as the traffic, when legitimated, should naturally extend, as the trade would be sure to extend, between two countries like Great Britain and Spain, alone capable of exchanging millions with each other for every million now operated. The L.1,500,000 thus gained would almost suffice to meet the annual interest on the L.34,000,000 loan conversion of 1834, still singularly classed in stock exchange parlance as "active stock." As for the remaining mass of domestic and foreign debt, there can be no hope for its gradual extinction but by the sale of national domains, in payment for which the titles of debt of all classes may be, as some now are, receivable in payment. As upwards of two thousand millions of reals of debt are said to be thus already extinguished, and the national domains yet remaining for disposal are valued at nearly the same sum, say L.20,000,000, it is clear that the final extinction of the debt is a hopeless prospect, although a very large reduction might be accomplished by that enhanced value of these domains which can only flow from increase of population and the rapid progression of industrial prosperity.

All Spain, excepting the confining provinces in the side of France, and especially the provinces where are the great commercial ports, such as Cadiz, Malaga,25 Corunna, &c., have laid before the Cortes and Government the most energetic memorials and remonstrances against the prohibition system of tariffs in force, and ask why they, who, in favour of their own industry and products, never asked for prohibitions, are to be sacrificed to Catalonia and Biscay? The Spanish Government and the most distinguished public men are well known to be favourable, to be anxiously meditating, an enlightened change of system, and negotiations are progressing prosperously, or would progress, but for France. When will France learn to imitate the generous policy which announced to her on the conclusion of peace with China—We have stipulated no conditions for ourselves from which we desire to exclude you or other nations?

We could have desired, for the pleasure and profit of the public, to extend our notice of, and extracts from, the excellent work of Señor Marliani, so often referred to, but our limits forbid. To show, however, the state and progress of the cotton manufacture in Catalonia, how little it gains by prohibitions, and how much it is prejudiced by the contraband trade, we beg attention to the following extract:—

"Since the year 1769, when the cotton manufacture commenced in Catalonia, the trade enjoyed a complete monopoly, not only in Spain, but also in her colonies. To this protection were added the fostering and united efforts of private individuals. In 1780, a society for the encouragement of the cotton manufacture was established in Barcelona. Well, what has been the result? Let us take the unerring test of figures for our guide. Let us take the medium importation of raw cotton from 1834 to 1840 inclusive, (although the latter year presents an inadmissible augmentation,) and we shall have an average amount of 9,909,261 lbs. of raw cotton. This quantity is little more than half that imported by the English in the year 1784. The sixteen millions of pounds imported that year by the English are less than the third part imported by the same nation in 1790, which amounted in all to thirty-one millions; it is only the sixth part of that imported in 1800, when it rose to 56,010,732 lbs.; it is less than the seventh part of the British importations in 1810, which amounted to seventy-two millions of pounds; it is less than the fifteenth part of the cotton imported into the same country in 1820, when the sum amounted to 150,672,655 pounds; it is the twenty-sixth part of the British importation in 1830, which was that year 263,961,452 lbs.; and lastly, the present annual importation into Catalonia is about the sixty-sixth part of that into Great Britain for the year 1840, when the latter amounted to 592,965,504 lbs. of raw cotton. Though the comparative difference of progress is not so great with France, still it shows the slow progress of the Catalonian manufactures in a striking degree. The quantity now imported of raw cotton into Spain is about the half of that imported into France from 1803 to 1807; a fourth part compared with French importations of that material from 1807 to 1820; seventh-and-a-half with respect to those of 1830; and a twenty-seventh part of the quantity introduced into France in 1840."

And we conclude with the following example, one among several which Señor Marliani gives, of the daring and open manner in which the operations of the contrabandistas are conducted, and of the scandalous participation of authorities and people—incontestable evidences of a wide-spread depravation of moral sentiments.

"Don Juan Prim, inspector of preventive service, gave information to the Government and revenue board in Madrid, on the 22d of November 1841, that having attempted to make a seizure of contraband goods in the town of Estepona, in the province of Malaga, where he was aware a large quantity of smuggled goods existed, he entered the town with a force of carabineers and troops of the line. On entering, he ordered the suspected depôt of goods to be surrounded, and gave notice to the second alcalde of the town to attend to assist him in the search. In some time the second alcalde presented himself, and at the instance of M. Prim dispersed some groups of the inhabitants who had assumed a hostile attitude. In a few minutes after, and just as some shots were fired, the first alcalde of the town appeared, and stated that the whole population was in a state of complete excitement, and that he could not answer for the consequences; whereupon he resigned his authority. While this was passing, about 200 men, well armed, took up a position upon a neighbouring eminence, and assumed a hostile attitude. At the same time a carabineer, severely wounded from the discharge of a blunderbuss, was brought up, so that there was nothing left for M. Prim but to withdraw his force immediately out of the town, leaving the smugglers and their goods to themselves, since neither the alcaldes nor national guards of the town, though demanded in the name of the law, the regent, and the nation, would aid M. Prim's force against them!"

All that consummate statesmanship can do, will be done, doubtless, by the present Government of Great Britain, to carry out and complete the economical system on which they have so courageously thrown themselves en avant, by the negotiation and completion of commercial treaties on every side, and by the consequent mitigation or extinction of hostile tariffs. Without this indispensable complement of their own tariff reform, and low prices consequent, he must be a bold man who can reflect upon the consequences without dismay. Those consequences can benefit no one class, and must involve in ruin every class in the country, excepting the manufacturing mammons of the Anti-corn-law league, who, Saturn-like, devour their own kindred, and salute every fall of prices as an apology for grinding down wages and raising profits. It may be well, too, for sanguine young statesmen like Mr Gladstone to turn to the DEBT, and cast about how interest is to be forthcoming with falling prices, falling rents, falling profits, (the exception above apart,) excise in a rapid state of decay, and customs' revenue a blank!

1

This was not the only case of compensation made out against this travelling companion. "Milord," says our tourist, "in his quality of bulldog, was so great a destroyer of cats, that we judged it wise to take some precautions against overcharges in this particular. Therefore, on our departure from Genoa, in which town Milord had commenced his practices upon the feline race of Italy, we enquired the price of a full-grown, well-conditioned cat, and it was agreed on all hands that a cat of the ordinary species—grey, white, and tortoiseshell—was worth two pauls—(learned cats, Angora cats, cats with two heads or three tails, are not, of course, included in this tariff.) Paying down this sum for two several Genoese cats which had been just strangled by our friend, we demanded a legal receipt, and we added successively other receipts of the same kind, so that this document became at length an indisputable authority for the price of cats throughout all Italy. As often as Milord committed a new assassination, and the attempt was made to extort from us more than two pauls as the price of blood, we drew this document from our pocket, and proved beyond a cavil that two pauls was what we were accustomed to pay on such occasions, and obstinate indeed must have been the man or woman who did not yield to such a weight of precedent."

2

It is amusing to contrast the artistic manner in which our author makes all his statements, with the style of a guide-book, speaking on the manufactures and industry of Florence. It is from Richard's Italy we quote. Mark the exquisite medley of humdrum, matter-of-fact details, jotted down as if by some unconscious piece of mechanism:—"Florence manufactures excellent silks, woollen cloths, elegant carriages, bronze articles, earthenware, straw hats, perfumes, essences, and candied fruits; also, all kinds of turnery and inlaid work, piano-fortes, philosophical and mathematical instruments, &c. The dyes used at this city are much admired, particularly the black, and its sausages are famous throughout all Italy.

3

The extreme misery of the paupers in Sicily, who form, he tells us, a tenth part of the population, quite haunts the imagination of M. Dumas. He recurs to it several times. At one place he witnesses the distribution, at the door of a convent, of soup to these poor wretches, and gives a terrible description of the famine-stricken group. "All these creatures," he continues, "had eaten nothing since yesterday evening. They had come there to receive their porringer of soup, as they had come to-day, as they would come to-morrow. This was all their nourishment for twenty-four hours, unless some of them might obtain a few grani from their fellow-citizens, or the compassion of strangers; but this is very rare, as the Syracusans are familiarized with the spectacle, and few strangers visit Syracuse. When the distributor of this blessed soup appeared, there were unheard-of cries, and each one rushed forward with his wooden bowl in his hand. Only there were some too feeble to exclaim, or to run, and who dragged themselves forward, groaning, upon their hands and knees. There was in the midst of all, a child clothed, not in anything that could be called a shirt, but a kind of spider's web, with a thousand holes, who had no wooden bowl, and who wept with hunger. It stretched out its poor little meagre hands, and joined them together, to supply as well as it could, by this natural receptacle, the absent bowl. The cook poured in a spoonful of the soup. The soup was boiling, and burned the child's hand. It uttered a cry of pain, and was compelled to open its fingers, and the soup fell upon the pavement. The child threw itself on all fours, and began to eat in the manner of a dog."—Vol. iii. p. 58.

And in another place he says, "Alas, this cry of hunger! it is the eternal cry of Sicily; I have heard nothing else for three months. There are miserable wretches, whose hunger has never been appeased, from the day when, lying in their cradle, they began to draw the milk from their exhausted mothers, to the last hour when, stretched on their bed of death, they have expired endeavouring to swallow the sacred host which the priest had laid upon their lips. Horrible to think of! there are human beings to whom, to have eaten once sufficiently, would be a remembrance for all their lives to come."—Vol. iv. p. 108.

4

Lar is the Tartar plural of all substantives.

5

Beaters for the game.

6

Rather less than an English yard.

7

The Tartars have an invariable custom, of taking off some part of their dress and giving it to the bearer of good news.

8

Coin.

9

Shakhéeds, traders of the sect of Souni. Yakhoúnt the senior moóllah.

10

Of the two opening lines we subjoin the original—to the vivacity and spirit of which it is, perhaps, impossible to do justice in translation:—

"Ihr—Ihr dort aussen in der Welt, Die Nasen einges pannt!"Eberhard, Count of Wurtemberg, reigned from 1344 to 1392. Schiller was a Swabian, and this poem seems a patriotic effusion to exalt one of the heroes of his country, of whose fame (to judge by the lines we have just quoted) the rest of the Germans might be less reverentially aware.

11

Schiller lived to reverse, in the third period of his intellectual career, many of the opinions expressed in the first. The sentiment conveyed in these lines on Rousseau is natural enough to the author of "The Robbers," but certainly not to the poet of "Wallenstein" and the "Lay of the Bell." We confess we doubt the maturity of any mind that can find either a saint or a martyr in Jean Jacques.

12

"Und Empfindung soll mein Richtschwert seyn."

A line of great vigour in the original, but which, if literally translated, would seem extravagant in English.

13

Joseph, in the original.

14

"The World was sad, the garden was a wild, And Man, the Hermit, sigh'd—till Woman smiled." CAMPBELL.15

Literally, "the eye beams its sun-splendour," or, "beams like a sun." For the construction that the Translator has put upon the original (which is extremely obscure) in the preceding lines of the stanza, he is indebted to Mr Carlyle. The general meaning of the Poet is, that Love rules all things in the inanimate or animate creation; that, even in the moral world, opposite emotions or principles meet and embrace each other. The idea is pushed into an extravagance natural to the youth, and redeemed by the passion, of the Author. But the connecting links are so slender, nay, so frequently omitted, in the original, that a certain degree of paraphrase in many of the stanzas is absolutely necessary to supply them, and render the general sense and spirit of the poem intelligible to the English reader.

16

Mr Shaw's researches include some curious physiological and other details, for an exposition of which our pages are not appropriate. But we shall here give the titles of his former papers. "An account of some Experiments and Observations on the Parr, and on the Ova of the Salmon, proving the Parr to be the Young of the Salmon."—Edinburgh New Phil. Journ. vol. xxi. p. 99. "Experiments on the Development and Growth of the Fry of the Salmon, from the Exclusion of the Ovum to the Age of Six Months."—Ibid. vol. xxiv. p. 165. "Account of Experimental Observations on the Development and Growth of Salmon Fry, from the Exclusion of the Ova to the Age of Two Years."—Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, vol. xiv. part ii. (1840.) The reader will find an abstract of these discoveries in the No. of this Magazine for April 1840.

17

Mr Young has, however, likewise repeated and confirmed Mr Shaw's earlier experiments regarding the slow growth of salmon fry in fresh water, and the conversion of parr into smolts. We may add, that Sir William Jardine, a distinguished Ichthyologist and experienced angler, has also corroborated Mr Shaw's observations.

18

The existence in the rivers during spring, of grilse which have spawned, and which weigh only three or four pounds, is itself a conclusive proof of this retardation of growth in fresh water. These fish had run, as anglers say—that is, had entered the rivers about midsummer of the preceding year—and yet had made no progress. Had they remained in the sea till autumn, their size on entering the fresh waters would have been much greater; or had they spawned early in winter, and descended speedily to the sea, they might have returned again to the river in spring as small salmon, while their more sluggish brethren of the same age were still in the streams under the form of grilse. All their growth, then, seems to take place during their sojourn in the sea, usually from eight to twelve weeks. The length of time spent in the salt waters, by grilse and salmon which have spawned, corresponds nearly to the time during which smolts remain in these waters; the former two returning as clean salmon, the last-named making their first appearance in our rivers as grilse.

19

Mr Shaw, for example, states the following various periods as those which he found to elapse between the deposition of the ova and the hatching of the fry—90, 101, 108, and 131 days. In the last instance, the average temperature of the river for eight weeks, had not exceeded 33°.

20

If we are rightly informed, salmon were not in the habit of spawning in the rivulets which run into Loch Shin, till under the direction of Lord Francis Egerton some full-grown fish were carried there previous to the breeding season. These spawned; and their produce, as was to be expected, after descending to the sea, returned in due course, and, making their way through the loch, ascended their native tributaries.

21

A complete series of specimens, from the day of hatching till about the middle of the sixth year, has been deposited by Mr Shaw in the Museum of the Royal Society of Edinburgh.

22

Mr Shaw informs us, moreover, that if those individuals which have assumed the silvery lustre be forcibly detained for a month or two in fresh water, they will resume the coloured coating which they formerly bore. The captive females, he adds, manifested symptoms of being in a breeding state by the beginning of the autumn of their third year. They were, in truth, at this time as old as herlings, though not of corresponding size, owing to the entire absence of marine agency.

23

Another interesting result may be noticed in connexion with this Compensation Pond. The original streamlet, like most others, was naturally stocked with small "burn-trout," which never exceeded a few ounces in weight, as their ultimate term of growth. But, in consequence of the formation above referred to, and the great increase of their productive feeding-ground, and tranquil places for repose and play, these tiny creatures have, in some instances, attained to an enormous size. We lately examined one which weighed six pounds. It was not a sea-trout, but a common fresh-water one—Salmo fario. This strongly exemplifies the conformable nature of fishes; that is, their power of adaptation to a change of external circumstances. It is as if a small Shetland pony, by being turned into a clover field, could be expanded into the gigantic dimensions of a brewer's horse.

24

The specimen is preserved in the Museum of the Royal Society of Edinburgh.

25

See Exposicion de que dirige á las Cortes et Ayuntamiento Constitucional de Malaga, from which the following are extracts:—"El ayuntamiento no puede menos de indicar, que entre los infinitos renglones fabriles aclimatados ya en Espana, las sedas de Valencia, los panos de muchas provincias, los hilados de Galicia, las blondas de Cataluna, las bayetas de Antequera, los hierros de Vizcaya y los elaborados por maquinaria en las ferrerías á un lado y otro de esta ciudad, han adelantado, prosperan y compiten con los efectos extranjeros mas acreditados. ¿Y han solicitado acaso una prohibicion? Nó jamas: un derecho protector, sí; á su sombra se criaron, con la competencia se formaron y llegaron á su robustez.... Ingleterra figura en la exportacion por el mayor valor sin admitir comparacion alguna. Su gobierno piensa en reducir muy considerablemente todos los renglones de su arancil; pero se ha espresado con reserva para negar ó conceder, si lo estima conveniente, esta reduccion á las naciones que no correspondan á los beneficios que les ofrece; ninguno puede esperar que le favorezcan sin compensacion."