полная версия

полная версияBlackwood's Edinburgh Magazine — Volume 53, No. 331, May, 1843

But that which naturalists have been unable to accomplish, has, so far as concerns the two invaluable species just alluded to, been achieved by others with no pretension to the name; and we now propose to present our readers with a brief sketch of what we conceive to be the completed biography of salmon and sea-trout. In stating that our information has been almost entirely derived from the researches of practical men, we wish it to be understood, and shall afterwards endeavour to demonstrate, that these researches have, nevertheless, been conducted upon those inductive principles which are so often characteristic of natural acuteness of perception, when combined with candour of mind and honesty of purpose. We believe it to be the opinion of many, that statements by comparatively uneducated persons are less to be relied upon than those of men of science. It may, perhaps, be somewhat difficult to define in all cases what really constitutes a man of science. Many sensible people suppose, that if a person pursues an original truth, and obtains it—that is, if he ascertains a previously unknown or obscure fact of importance, and states his observations with intelligence—he is entitled to that character, whatever his station may be. For ourselves, we would even say that if his researches are truly valuable, he is himself all the more a man of science in proportion to the difficulties or disadvantages by which his position in life may be surrounded.

The development and early growth of salmon, from the ovum to the smolt, were first successfully investigated by Mr John Shaw of Drumlanrig, one of the Duke of Buccleuch's gamekeepers in the south of Scotland. Its subsequent progress from the smolt to the adult condition, through the transitionary state of grilse, has been more recently traced, with corresponding care, by Mr Andrew Young of Invershin, the manager of the Duke of Sutherland's fisheries in the north. Although the fact of the parr being the young of the salmon had been vaguely surmised by many, and it was generally admitted that the smaller fish were never found to occur except in streams or tributaries to which the grown salmon had, in some way, the power of access, yet all who have any acquaintance with the works of naturalists, will acknowledge that the parr was universally described as a distinct species. It is equally certain that all who have written upon the subject of smolts or salmon-fry, maintained that these grew rapidly in fresh water, and made their way to the sea in the course of a few weeks after they were hatched.

Now, Mr Shaw's discovery in relation to these matters is in a manner twofold; first—he ascertained by a lengthened series of rigorous and frequently-repeated experimental observations, that parr are the early state of salmon, being afterwards converted into smolts; secondly,—he proved that such conversion does not, under ordinary circumstances take place until the second spring ensuing that in which the hatching has occurred, by which time the young are two years old. The fact is, that during early spring there are three distinct broods of parr or young salmon in our rivers.

1st, We have those which, recently excluded from the ova, are still invisible to common eyes; or, at least, are inconspicuous or unobservable. Being weak, in consequence of their recent emergence from the egg, and of extremely small dimensions, they are unable to withstand the rapid flow of water, and so betake themselves to the gentler eddies, and frequently enter "into the small hollows produced in the shingle by the hoofs of horses which have passed the fords." In these and similar resting-places, our little natural philosophers, instinctively aware that the current of a stream is less below than above, and along the sides than in the centre, remain for several months during spring, and the earlier portion of the summer, till they gain such an increase of size and strength as enables them to spread themselves abroad over other portions of the river, especially those shallow places where the bottom is composed of fine gravel. But at this time their shy and shingle-seeking habits in a great measure screen them from the observance of the uninitiated.

2dly, We have likewise, during the spring season, parr which have just completed their first year. As these have gained little or no accession of size during the winter months, owing to the low temperature both of the air and water, and the consequent deficiency of insect food, their dimensions are scarcely greater than at the end of the preceding October: that is, they measure in length little more than three inches.—(N.B. The old belief was that they grew nine inches in about three weeks, and as suddenly sought the turmoil of the sea.) They increase, however in size as the summer advances, and are then the declared and admitted parr of anglers and other men.

3dly, Simultaneously with the two preceding broods, our rivers are inhabited during March and April by parr which have completed their second year. These measure six or seven inches in length, and in the months of April and May they assume the fine silvery aspect which characterizes their migratory condition,—in other words, they are converted into smolts, (the admitted fry of salmon,) and immediately make their way towards the sea.

Now, the fundamental error which pervaded the views of previous observers of the subject, consisted in the sudden sequence which they chose to establish between the hatching of the ova in early spring, and the speedy appearance of the acknowledged salmon-fry in their lustrous dress of blue and silver. Observing, in the first place, the hatching of the ova, and, erelong, the seaward migration of the smolts, they imagined these two facts to take place in the relation of immediate or connected succession; whereas they had no more to do with each other than an infant in the nursery has to do with his elder, though not very ancient, brother, who may be going to school. The rapidity with which the two-year-old parr are converted into smolts, and the timid habits of the new-hatched fry, which render them almost entirely invisible during the first few months of their existence,—these two circumstances combined, have no doubt induced the erroneous belief that the silvery smolts were the actual produce of the very season in which they are first observed in their migratory dress: that is, that they were only a few weeks old, instead of being upwards of two years. It is certainly singular, however, that no enquirer of the old school should have ever bethought himself of the mysterious fate of the two-year-old parr, (supposing them not to be young salmon,) none of which, of course, are visible after the smolts have taken their departure to the sea. If the two fish, it may be asked, are not identical, how does it happen that the one so constantly disappears along with the other? Yet no one alleges that he has ever seen parr as such, making a journey towards the sea "They cannot do so" says Mr Shaw, "because they have been previously converted into smolts."

Mr Shaw's investigations were carried on for a series of years, both on the fry as it existed naturally in the river, and on captive broods produced from ova deposited by adult salmon, and conveyed to ingeniously-constructed experimental ponds, in which the excluded young were afterwards nourished till they threw off the livery of the parr, and underwent their final conversion into smolts. When this latter change took place, the migratory instinct became so strong that many of them, after searching in vain to escape from their prison—the little streamlet of the pond being barred by fine wire gratings—threw themselves by a kind of parabolic somerset upon the bank and perished. But, previous to this, he had repeatedly observed and recorded the slowly progressive growth to which we have alluded. The value of the parr, then, and the propriety of a judicious application of our statutory regulations to the preservation of that small, and, as hitherto supposed, insignificant fish, will be obvious without further comment.16

Having now exhibited the progress of the salmon fry from the ovum to the smolt, our next step shall be to show the connexion of the latter with the grilse. As no experimental observations regarding the future dimensions of the détenus of the ponds could be regarded as legitimate in relation to the usual increase of the species, (any more than we could judge of the growth of a young English guardsman in the prisons of Verdun,) after the period of their natural migration to the sea, and as Mr Shaw's distance from the salt water—twenty-five miles, we believe, windings included—debarred his carrying on his investigations much further with advantage, he wisely turned his attention to a different, though cognate subject, to which we shall afterwards refer. We are, however, fortunately enabled to proceed with our history of the adolescent salmon by means of another ingenious observer already named, Mr Andrew Young of Invershin.

It had always been the prevailing belief that smolts grew rapidly into grilse, and the latter into salmon. But as soon as we became assured of the gross errors of naturalists, and all other observers, regarding the progress of the fry in fresh water, and how a few weeks had been substituted for a period of a couple of years, it was natural that considerate people should suspect that equal errors might pervade the subsequent history of this important species. It appears, however, that marine influence (in whatever way it works) does indeed exercise a most extraordinary effect upon those migrants from our upland streams, and that the extremely rapid transit of a smolt to a grilse, and of the latter to an adult salmon, is strictly true. Although Mr Young's labours in this department differ from Mr Shaw's, in being rather confirmatory than original, we consider them of great value, as reducing the subject to a systematic form, and impressing it with the force and clearness of the most successful demonstration.

Mr Young's first experiments were commenced as far back as 1836, and were originally undertaken with a view to show whether the salmon of each particular river, after descending to the sea, returned again to their original spawning-beds, or whether, as some supposed, the main body, returning coastwards from their feeding grounds in more distant parts of the ocean, and advancing along our island shores, were merely thrown into, or induced to enter, estuaries and rivers by accidental circumstances; and that the numbers obtained in these latter localities thus depended mainly on wind and weather, or other physical conditions, being suitable to their upward progress at the time of their nearing the mouths of the fresher waters. To settle this point, he caught and marked all the spawned fish which he could obtain in the course of the winter months during their sojourn in the rivers. As soon as he had hauled the fish ashore, he made peculiar marks in their caudal fins by means of a pair of nipping-irons, and immediately threw then back into the water. In the course of the following fishing season great numbers were recaptured on their return from the sea, each in its own river bearing its peculiar mark. "We have also," Mr Young informs us, "another proof of the fact, that the different breeds or races of salmon continue to revisit their native streams. You are aware that the river Shin falls into the Oykel at Invershin, and that the conjoined waters of these rivers, with the Carron and other streams, form the estuary of the Oykel, which flows into the more open sea beyond, or eastwards of the bar, below the Gizzen Brigs. Now, were the salmon which enter the mouth of the estuary at the bar thrown in merely by accident or chance, we should expect to find the fish of all the various rivers which form the estuary of the same average weight; for, if it were a mere matter of chance, then a mixture of small and great would occur indifferently in each of the interior streams. But the reverse of this is the case. The salmon in the Shin will average from seventeen pounds to eighteen pounds in weight, while those of the Oykel scarcely attain an average of half that weight. I am, therefore, quite satisfied, as well by having marked spawned fish descending to the sea, and caught them ascending the same river, and bearing that river's mark, as by a long-continued general observation of the weight, size, and even something of the form, that every river has its own breed, and that breed continues, till captured and killed, to return from year to year into its native stream."

We have heard of a partial exception to this instinctive habit, which, however, essentially confirms the rule. We are informed that a Shin salmon (recognized as such by its shape and size) was, on a certain occasion, captured in the river Conon, a fine stream which flows into the upper portion of the neighbouring Frith of Cromarty. It was marked and returned to the river, and was taken next day in its native stream the Shin, having, on discovering its mistake, descended the Cromarty Frith, skirted the intermediate portion of the outer coast by Tarbet Ness, and ascended the estuary of the Oykel. The distance may be about sixty miles. On the other hand, we are informed by a Sutherland correspondent of a fact of another nature, which bears strongly upon the pertinacity with which these fine fish endeavour to regain their spawning ground. By the side of the river Helmsdale there was once a portion of an old channel forming an angular bend with the actual river. In summer, it was only partially filled by a detached or landlocked pool, but in winter, a more lively communication was renewed by the superabounding waters. This old channel was, however, not only resorted to by salmon as a piece of spawning ground during the colder season of the year, but was sought for again instinctively in summer during their upward migration, when there was no water running through it. The fish being, of course, unable to attain their object, have been seen, after various aerial boundings, to fall, in the course of their exertions, upon the dry gravel bank between the river and the pool of water, where they were picked up by the considerate natives.

No sooner had Mr Young satisfied himself that the produce of a river invariably returned to that river after descending to the sea, than he commenced his operations upon the smolts—taking up the subject where it was unavoidably left off by Mr Shaw17. His long-continued superintendence of the Duke of Sutherland's fisheries in the north of Scotland, and his peculiar position as residing almost within a few yards of the noted river Shin, afforded advantages of which he was not slow to make assiduous use. He has now performed numerous and varied experiments, and finds that, notwithstanding the slow growth of parr in fresh water, "such is the influence of the sea as a more enlarged and salubrious sphere of life, that the very smolts which descend into it from the rivers in spring, ascend into the fresh waters in the course of the immediate summer as grilse, varying in size in proportion to the length of their stay in salt water."

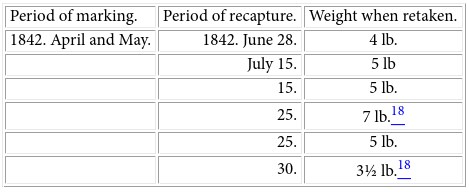

For example, in the spring of 1837, Mr Young marked a great quantity of descending smolts, by making a perforation in their caudal fins with a small pair of nipping-irons constructed for the purpose, and in the ensuing months of June and July he recaptured a considerable number on their return to the rivers, all in the condition of grilse, and varying from 3lbs. to 8lbs., "according to the time which had elapsed since their first departure from the fresh water, or, in other words, the length of their sojourn in the sea." In the spring of 1842, he likewise marked a number of descending smolts, by clipping off what is called the adipose fin upon the back. In the course of the ensuing June and July, he caught them returning up the river, bearing his peculiar mark, and agreeing with those of 1837 both in respect to size, and the relation which that size bore to the lapse of time.

The following list from Mr Young's note-book, affords a few examples of the rate of growth:—

List of Smolts marked in the River, and recaptured as Grilse on their first ascent from the Sea.

18These two specimens are now preserved in the Museum of the Royal Society of Edinburgh.

We may now proceed to consider the final change,—that of the grilse into the adult salmon. We have just seen that smolts return to the rivers as grilse, (of the weights above noted,) during the summer and autumn of the same season in which they had descended for the first time to the sea. Such as seek the rivers in the earlier part of summer are of small size, because they have sojourned for but a short time in the sea:—such as abide in the sea till autumn, attain of course a larger size. But it appears to be an established, though till now an unknown fact, that with the exception of the early state of parr, in which the growth has been shown to be extremely slow, salmon actually never do grow in fresh water at all, either as grilse or in the adult state. All their growth in these two most important later stages, takes place during their sojourn in the sea. "Not only," says Mr Young, "is this the case, but I have also ascertained that they actually decrease in dimensions after entering the river, and that the higher they ascend the more they deteriorate both in weight and quality. In corroboration of this I may refer to the extensive fisheries of the Duke of Sutherland, where the fish of each station of the same river are kept distinct from those of another station, and where we have had ample proof that salmon habitually decrease in weight in proportion to their time and distance from the sea."18

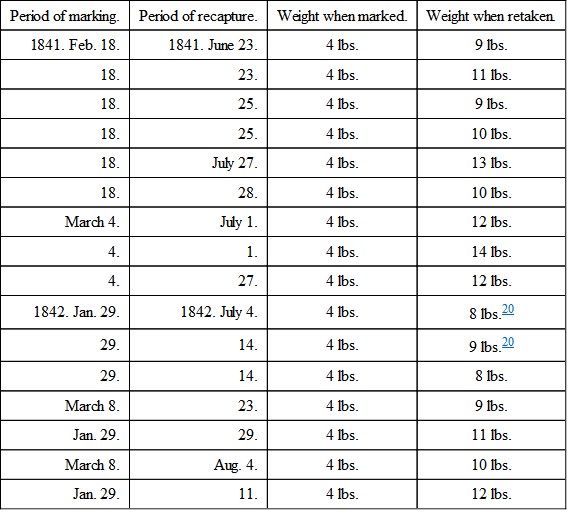

Mr Young commenced marking grilses, with a view to ascertain that they became salmon, as far back as 1837, and has continued to do so ever since, though never two seasons with the same mark. We shall here record only the results of the two preceding years. In the spring of 1841, he marked a number of spawned grilse soon after the conclusion of the spawning period. Taking his "net and coble," he fished the river for the special purpose, and all the spawned grilse of 4 lb. weight were marked by putting a peculiarly twisted piece of wire through the dorsal fin. They were immediately thrown into the river, and of course disappeared, making their way downwards with other spawned fish towards the sea. "In the course of the next summer we again caught several of those fish which we had thus marked with wire as 4 lb. grilse, grown in the short period of four or five months into beautiful full-formed salmon, ranging from 9 lb. to 14 lb. in weight, the difference still depending on the length of their sojourn in the sea."

In January 1842, he repeated the same process of marking 4 lb. grilse which had spawned, and were therefore about to seek the sea; but, instead of placing the wire in the back fin, he this year fixed it in the upper lobe of the tail, or caudal fin. On their return from the sea, he caught many of these quondam grilse converted into salmon as before. The following lists will serve to illustrate the rate of growth:—

List of Grilse marked after having spawned, and re-captured as Salmon, on their second ascent from the Sea.

20These two specimens, with their wire marks in situ, may now be seen in the Museum of the Royal Society of Edinburgh.

During both these seasons, Mr Young informs us, he caught far more marked grilse returning with the form and attributes of perfect salmon, than are recorded in the preceding lists. "In many specimens the wires had been torn from the fins, either by the action of the nets or other casualties; and, although I could myself recognise distinctly that they were the fish I had marked, I kept no note of them. All those recorded in my lists returned and were captured with the twisted wires complete, the same as the specimens transmitted for your examination."

We agree with Mr Young in thinking that the preceding facts, viewed in connexion with Mr Shaw's prior observations, entitle us to say, that we are now well acquainted with the history and habits of the salmon, and its usual rate of growth from the ovum to the adult state. The young are hatched after a period which admits of considerable range, according to the temperature of the season, or the modifying character of special localities.19 They usually burst the capsule of the egg in 90 to 100 days after deposition, but they still continue for a considerable time beneath the gravel, with the yelk or vitelline portion of the egg adhering to the body; and from this appendage, which Mr Shaw likens to a red currant, they probably derive their sole nourishment for several weeks. But though the lapse of 140 or even 150 days from the period of deposition is frequently required to perfect the form of these little fishes, which even then measure scarcely more than an inch in length, their subsequent growth is still extremely slow; and the silvery aspect of the smolt is seldom assumed till after the expiry of a couple of years. The great mass of these smolts descend to the sea during the months of April and May,—the varying range of the spawning and hatching season carrying with it a somewhat corresponding range in the assumption of the first signal change, and the consequent movement to the sea. They return under the greatly enlarged form of grilse, as already stated, and these grilse spawn that same season in common with the salmon, and then both the one and the other re-descend into the sea in the course of the winter or ensuing spring. They all return again to the rivers sooner or later, in accordance, as we believe, with the time they had previously left it after spawning, early or late. The grilse have now become salmon by the time of their second ascent from the sea; and no further change takes place in their character or attributes, except that such as survive the snares of the fishermen, the wily chambers of the cruives, the angler's gaudy hook, or the poacher's spear, continue to increase in size from year to year. Such, however, is now the perfection of our fisheries, and the facilities for conveying this princely species even from our northern rivers, and the "distant islands of the sea," to the luxurious cities of more populous districts, that we greatly doubt if any salmon ever attains a good old age, or is allowed to die a natural death. We are not possessed of sufficient data from which to judge either of their natural term of life, or of their ultimate increase of size. They are occasionally, though rarely, killed in Britain of the weight of forty and even fifty pounds. In the comparatively unfished rivers of Scandinavia large salmon are much more frequent, although the largest we ever heard of was an English fish which came into the possession of Mr Groves, of Bond Street. It was a female, and weighed eighty-three pounds. In the year 1841, Mr Young marked a few spawned salmon along with his grilse, employing as a distinctive mark copper wire instead of brass. One of these, weighing twelve pounds, was marked on the 4th of March, and was recaptured on returning from the sea on the 10th of July, weighing eighteen pounds. But as we know not whether it made its way to the sea immediately after being marked, we cannot accurately infer the rate of increase. It probably becomes slower every year, after the assumption of the adult state. Why the salmon of one river should greatly exceed the average weight of those of another into which it flows, is a problem which we cannot solve. The fact, for example, of the river Shin flowing from a large lake, with a course of only a few miles, into the Oykel, although it accounts for its being an early river, owing to the receptive depth, and consequently higher temperature of its great nursing mother, Loch Shin, in no way, so far at least as we can see, explains the great size of the Shin fish, which are taken in scores of twenty pounds' weight. They have little or nothing to do with the loch itself, haunting habitually the brawling stream, and spawning in the shallower fords, at some distance up, but still below the great basin;20 and there are no physical peculiarities which in any way distinguish the Shin from many other lake born northern rivers, where salmon do not average half the size.