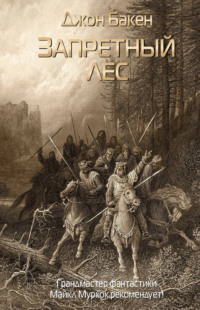

Полная версия

The Thirty-Nine Steps. Selected Stories / 39 ступеней. Избранные новеллы

At about five o'clock the carriage was finally empty, and I was left alone. I got out at the next station, a little place set right in the heart of a bog. Soon I found myself on a white road that went over the brown moor. It was a fine spring evening. The air had the queer smell of bogs, but it had the strangest effect on me. I felt light-hearted like a boy on a spring holiday, and not a man of thirty-seven, wanted by the police. I decided that I was still far ahead of any pursuit. There was no plan in my head, only just to go on and on in this hill country.

I was getting very hungry when I came to a shepherd's cottage beside a waterfall. A woman, who was standing by the door, greeted me. When I asked for a place to spend the night, she said I was welcome to the 'bed in the loft', and very soon she set before me a meal of ham and eggs.

In the evening her husband came back from the hills. They asked me no questions, but I could see they thought I was a kind of cattle dealer. So I spoke a lot about cattle, of which they knew very little, and I learned from them a lot about the local Galloway markets.

I woke up at five the next morning, had breakfast at six, and then was on my way again. My kind hosts didn't take any payment. My plan was to get to the next railway station and to go some way back. I thought that that was the safest way because the police would think that I was always going farther from London.

The station, when I reached it, was ideal for my purpose. The moor was around it, making it quite isolated. There was no road to it from anywhere. I waited in the heather till I saw the smoke of a train on the horizon. Then I came up to the tiny booking-office and took a ticket for Dumfries.

The only passengers in the carriage were an old shepherd and his dog. The man was asleep, and beside him was that morning's newspaper. I took it, hoping it would tell me something.

There were two columns about the Portland Place Murder, as it was called. My man Paddock had called the police, and the milkman had been arrested. Later the milkman had been let go, I read, and the true criminal had got away from London by one of the northern lines. There was a short note about me as the owner of the flat. I guessed the police had put that in, trying to tell me that I was not a suspect.

There was nothing else in the paper, nothing about foreign politics or Karolides, or the things that had interested Scudder. I put the paper back and saw that we were coming to the station at which I had got out yesterday. On the platform three men were talking to the station-master. I supposed that they were the local police, who had been called by Scotland Yard. Sitting in the shadow, I watched them carefully. One of them had a book and took notes. All four men looked at the moor and the white road.

As we moved away from that station, the shepherd woke up. He looked at me, kicked his dog, and asked where he was. I told him. Clearly he was very drunk.

'That's what happens when you're a teetotaler,' he said.

I showed my surprise.

'Ay, but I'm a strong teetotaler,' he said. 'I haven't touched a drop of whisky for a long time.'

'What did it then?' I asked.

'A drink they call brandy. Being a teetotaler, I kept off the whisky, but I was drinking this brandy,' he explained and fell asleep again.

My plan had been to get out at some station, but the train suddenly gave me a better chance because it came to a standstill at the end of a culvert. I looked out and saw that every carriage window was closed and there was no one in the landscape. So I opened the door and jumped into the bushes that grew along the line.

It would've been all right, but that shepherd's dog started to bark. I crawled through the bushes for a hundred yards or so. Then from there I looked back and saw the guard and several passengers standing at the open carriage door and staring in my direction. My departure was not unnoticed. When after a quarter of a mile's crawl I looked back again, the train had started and was disappearing into the distance.

There was moorland and the high hills around me, and not a sign or sound of a human being. Yet, for the first time I felt the terror. It was not the police that I thought of, but the other people who knew that I knew Scudder's secret and would not let me live. I was certain that they would follow me and when they found me, they would have no mercy. I looked back, but there was nothing in the landscape which was the most peaceful sight in the world. Nevertheless, I started to run.

I ran till I had reached the top of a mountain high above the moor. From there I could see the railway line. I have eyes like a hawk, but I could see nothing moving in the whole countryside. Then I looked east and saw another kind of landscape. There were green valleys with plantations and roads. Last of all, I looked into the blue May sky and froze.

In the south a small plane was rising into the sky. I was certain that that airplane was looking for me and that it did not belong to the police. For an hour or two I watched it hiding in the heather. It flew low along the hill-tops, and then in circles over the valley from which I had come. Then it rose to a greater height and flew away back to the south.

I did not like this espionage from the air, and I began to think about the countryside I had chosen for hiding. These heather hills were no good if my enemies were in the sky, and I had to find another place to hide. I looked at the green country beyond where I could find woods and stone houses.

At about six in the evening I came out of the moorland to a road which went along the narrow stream. As I followed it, in the twilight I reached a small house. The road went over a bridge, and there stood a young man. He was smoking a pipe and looking at the water. In his left hand was a small book.

He turned round when he heard my footsteps, and I saw a pleasant boyish face.

'Good evening to you,' he said. 'It's a fine night for the road.'

The smell of smoke and some tasty roast reached me from the house.

'Is that place an inn?' I asked.

'At your service,' he said politely. 'I am the landlord, Sir, and I hope you will stay the night. To tell you the truth, I have had no company for a week.'

'You're young to be an innkeeper,' I said and took out my pipe.

'My father died a year ago and left me the business. I live there with my grandmother. It's a slow job for a young man, and it wasn't my choice of profession.'

'Which was?'

He blushed. 'I want to write books,' he said.

'Well, I've often thought that an innkeeper would make the best story-teller in the world.'

'Not now,' he said. 'Maybe in the old days. But not now. Nothing happens here. There is not much material. I want to see life, to travel the world.'

'I've traveled the world a bit, and I wouldn't say that adventure is found only in the tropics. Maybe it's standing right next to you at this moment. Here's a true tale for you then,' I cried, 'and a month from now you can make a novel out of it.'

Sitting on the bridge in the soft May evening, I told him a lovely story. It was mostly true, though I changed some details. I said that I was a mining magnate from South Africa, who had had a lot of trouble with a gang. They had pursued me across the ocean, and had killed my best friend, and were now on my tracks. I told the story well. I described an attack on my life on the voyage home and the Portland Place murder.

'You're looking for adventure?' I cried. 'Well, you've found it here. The devils are after me, and the police are after them.'

'My God!' he whispered.

'You believe me?' I asked.

'Of course I do,' he said. 'I believe everything out of the ordinary.'

He was very young, but he was the man for my money.

'I think I must lie low[29] for a couple of days. Can you take me in?'

He pointed towards the house. 'You can lie low here. I'll make sure no one asks you questions. And you'll give me some more material about your adventures?'

As I was walking into the inn, I heard an engine. There, in the sky, was my friend – the little plane.

The young man gave me a room at the back of the house. I never saw the grandmother, but an old woman called Margit brought me my meals, and the innkeeper was around me all the time. I wanted some time to myself, so I invented a job for him. He had a motorcycle, and the next morning I sent him for the daily paper. I also told him to keep his eyes open for any strange figures, motors or airplanes.

He came back at midday with the paper. There was nothing in it, except some evidence of Paddock and the milkman, and the statement that the murderer had gone north. But there was a long article about Karolides and the affairs in the Balkans, though it did not mention any visits to England.

In the afternoon I sat down to work on Scudder's note-book. As I told you, it was a numerical cipher. The trouble was the key word, and I felt hopeless. But about three o'clock I had a sudden inspiration.

I remembered the name, Julia Czechenyi. Scudder had said it was the key to the Karolides business, and I decided to try it on his cipher. It worked. The five letters of 'Julia' gave me the position of the vowels. 'Czechenyi' gave me the numerals for the consonants. I wrote them on a piece of paper and sat down to read Scudder's pages.

In half an hour, while I was still reading it, I glanced out of the window and saw a big car coming towards the inn. It stopped at the door, and two people got out.

Ten minutes later the innkeeper came into the room. His eyes were bright with excitement.

'There are two chaps below, looking for you,' he whispered. 'They're in the dining-room, having drinks. They asked about you and said they had hoped to meet you here. Oh, and they described you well, even your boots and shirt. I told them you had been here last night and had gone off on a motorcycle this morning, and one of the chaps swore.'

I asked him to tell me what they looked like. One was a thin, dark-eyed fellow with thick eyebrows, and the other smiled and lisped in his talk.

I took a piece of paper and wrote these words in German: '…Black Stone. Scudder had got to this, but he could not act for two weeks. I doubt if I can do any good now, especially as Karolides is uncertain about his plans. But if Mr. T. advises I will do the best I.'

I made it look like a page of a private letter.

'Take this to them and say it was found in my bedroom, and ask them to give it to me when they see me.'

Three minutes later I heard the car engine start, and the innkeeper came back in great excitement.

'Your paper woke them up,' he said. 'The dark fellow went as white as death and cursed like hell, and the fat one whistled. They paid for their drinks and didn't wait for change.'

'Now I'll tell you what I want you to do,' I said. 'Get on your motorcycle and go to the police station. Describe the two men and say you think they have something to do with the London murder. You can invent reasons. The two will come back, that's for sure. Not tonight, as they'll follow me forty miles along the road, but probably tomorrow morning. Tell the police to be here early tomorrow.'

He went off, and I worked on Scudder's notes. When he came back, we had dinner together, and when he went to bed, I finally finished with Scudder. I smoked sitting in a chair till daylight because I could not sleep.

At about eight the next morning I saw the arrival of the policemen. They left their car behind the inn and entered the house. Twenty minutes later, I saw from my window a second car, coming from the opposite direction. It did not come up to the inn, but stopped two hundred yards off in the wood. A minute or two later I heard steps outside the window.

My plan had been to hide in my bedroom, and see what happened. I had an idea that if I could bring the police and my other more dangerous pursuers together, something might work out of it. But now I had a better idea. I wrote thanks to my host, opened the window, and quietly jumped down into a gooseberry bush. I ran to the trees along the road to where the car stood. I jumped into the driver's seat and started the engine. Almost immediately the road went downhill, so I couldn't see the inn, but the wind brought me the sounds of angry voices.

4

That shining May morning I was driving the car at high speed along the moor roads, thinking of what I had found in Scudder's pocket-book.

The little man had told me a lot of lies. All his tales about the Balkans, and the anarchists, and the Foreign Office Conference were lies, and so was Karolides. Yet not quite[30]. I had believed in his story enough to risk my own life, but he had let me down. His book was telling me a different tale, and I believed it absolutely. Why, I don't know.

The fifteenth of June was going to be a big day of destiny. It was so big that I wasn't surprised Scudder hadn't told me all about it. He had told me something which sounded big enough, but the real thing was so big that he – the man who had found it out – wanted it all for himself.

The whole story was in the notes with gaps. The four names he had written were authorities, and he had given them a numerical value. There was a man, Ducrosne, who got five, and another fellow, Ammersfoort, who got three. There also was one queer phrase which appeared several times, in brackets. It was '(Thirty-nine steps)', and the last time he used it, he wrote: '(Thirty-nine steps, I counted them, high tide 10.17p.m.)'. I could not understand that.

The first thing I learned was that it was not about preventing a war. The war was coming anyway. Karolides was going to be dead on June 14th, and nothing could prevent that.

The second thing was that this war was going to be a surprise for Britain. Karolides' death would anger the Balkans, and then Vienna would give an ultimatum. Russia wouldn't like that, but Berlin would play the peacemaker at first, then find a reason for a conflict and attack us. That was the idea.

But all this depended on the third thing, which would happen on June 15th. I had known back in my days in Africa that there was an alliance between France and Britain, and that the two countries could act together in case of war. Well, in June a very important man, Royer, was coming to London from Paris, and he was going to get information about the disposition of the British Fleet.

But on the 15th of June, other important people were going to be in London, too. Scudder simply called them the 'Black Stone'. They were not our allies, but rather our enemies. So the information intended for France could end up in their pockets.

This was the story I had deciphered in the country inn.

My first impulse had been to write a letter to the Prime Minister, but then I thought that it would be useless. Who would believe my tale? I must have some proof first. But what could that be? Most importantly, I had to keep going despite the fact that the police and the Black Stone were pursuing me.

I had no clear idea of my journey, but I kept going east. I drove along a river, through little old villages, over peaceful streams, and past gardens and parks. The land was so peaceful that I could hardly believe that in a month the country men would be lying dead in English fields.

At about midday I came to one village where I had planned to stop and eat. A policeman saw me and tried to make me stop. I almost did. Then I realized that the description of me and the car had been already sent to thirty villages through which I might pass. I sped up again and thought that main roads were no place for me. I turned onto a narrow lane, but without a map I could be turning onto a farm road and ending up in someone's yard.

What a fool I had been to steal the car! But even if I left it, it would be found in an hour or two, and I wouldn't get far enough either. The only thing to do now was not to take the main roads. The road I was driving along was taking me too far north, so I turned east along a bad track and finally reached a big double-line railway. Beyond it I saw another valley, and thought that if I crossed it I might find some inn to stay for the night. I was tired and hungry. Just then I heard a noise in the sky, and there was that airplane, flying low, coming towards me.

There were no trees on the moor, so I hurried to get to the valley. I went downhill, turning my head round to watch that plane. Soon I was on a road between hedges and slowed down a bit.

Suddenly on my left I heard the hoot of another car, and realized to my horror that I was running into a couple of posts of a private road. I stepped on my brakes, but it was too late. So I did the only thing possible and drove into the hedge on the right.

But it was a mistake. My car went through the hedge and then started falling forward. I saw what was coming. I tried to jump out and got caught on a branch of hawthorn which held me, while my car dropped fifty feet down to the stream below. This was a good way of getting rid of the car, I thought.

Slowly I crawled back to the road where a scared voice asked me if I was hurt. It was a tall young man from the other car.

'My fault, Sir,' I said to him. 'That's the end of my Scotch motor tour, but it might have been the end of my life.'

He looked at his watch. 'I have a quarter of an hour, and my house is two minutes away. I'll see that you have something to put on and eat. Where are all your things, by the way? Are they in the car?'

'They're in my pockets,' I said. 'I'm a Colonial and travel light.'[31]

'A Colonial,' he cried. 'Are you by any chance a Free Trader?[32]'

'I am,' said I, not knowing what he meant.

We got into his car, and three minutes later we stopped before a comfortable-looking cabin. He took me inside and first showed me half a dozen of his suits because my own had been torn. I chose a blue one, which made me look very different. Then he took me to the dining-room, where there was some food on the table, and told me that I had just five minutes to eat. I had a cup of coffee and some cold ham.

'You can take a snack in your pocket, and we'll have supper when we get back. I've got to be at the Masonic Hall at eight o'clock. I'm in a mess right now, Mr… you haven't told me your name. Twisdon? Well, Mr. Twisdon, you see I'm Liberal Candidate for this part of the world, and I have a meeting tonight. The Colonial ex-Premier, Crumpleton, was supposed to come[33] and speak for me, but he got ill. Here I am, left to do the whole thing myself! I had planned to speak for ten minutes and must now go on for forty. The problem is I cannot think of anything to say, and you've got to help me. You're a Free Trader and can tell our people about the Colonies. I'll be for ever in your debt.'

I thought how odd it was to ask a stranger who had almost died and had lost an expensive car to speak at a meeting for him. I knew very little about Free Trade, but I saw no other chance to get what I wanted.

'All right,' I said. 'I'm not a good speaker, but I'll tell them a bit about Australia.'

On the way he told me the simple facts of his history. He was an orphan, and his uncle who was in the Cabinet had brought him up. His uncle had advised politics, and the young man had no preference in parties. 'Good friends in both,' he said, 'and plenty of enemies, too. I'm Liberal, because my family have always been Whigs[34].' Altogether, he was a very clean, decent young man.

As we passed through a little town, two policemen stopped us.

'Pardon, Sir Harry,' said one. 'We've been looking for a car like yours.'

'All right,' said my host. After that we didn't speak anymore because he was busy thinking about his coming speech, and I began to prepare myself for a disaster. I tried to think of something I could say, but my mind was dry.

Finally we stopped outside a door in a street, and were welcomed by some noisy gentlemen. The hall had about five hundred people in it, mostly women and old men. The chairman commented on Crumpleton's absence and introduced me as a 'leader of Australian thought'. Then Sir Harry started. I never heard anything like it. He didn't know how to talk. He had a lot of notes from which he read. He talked about the 'German menace', and said it was a Tory[35] invention. He was for reducing our Navy and then sending Germany an ultimatum telling her to do the same.

Yet I liked his speech. It took a load off my mind. I wasn't much of a speaker, but I was much, much better than Sir Harry.

When it was my turn, I simply told them all I could remember about Australia. I doubt if I ever mentioned Free Trade, but I said there were no Tories in Australia, only Labor and Liberals. Altogether I think I was a success.

When we were in the car again, my host was in good spirits[36]. 'Excellent speech, Twisdon,' he said. 'Now, you're coming home with me. I'm all alone, and if you stay for a day or two, I'll show you some very decent fishing.'

We had a hot supper and then drank grog in a big smoking-room. I thought it was the time for me to put my cards on the table. I saw that he was the man I could trust.

'Listen, Sir Harry,' I said. 'I've something very important to say to you. You're a good fellow, and I'm going to be frank. What you said about Germany.'

'Why? What's wrong? Was it that bad?' he asked. 'But you don't think Germany would ever go to war with us?'

'If you give me half an hour, I am going to tell you a story,' I said.

It was the first time I had ever told anyone the truth. I left out no detail. He heard all about Scudder, and the milkman, and the note-book, and my adventures in Galloway.

'So you see,' I said, 'I am the man that is wanted for the Portland Place murder. You could call the police and give me up. I don't think I'll get very far.'

He got very excited and was looking at me with bright eyes. 'What was your job in Rhodesia, Mr. Hannay?' he asked.

'Mining engineer,' I said.

He watched me with a smile. 'I may be a bad speaker, but I can see that you're no murderer and you're no fool, and I believe you are telling the truth. I'm going to help you. Now, what can I do?'

'First, I want you to write a letter to your uncle. I've got to get in touch with the Government people sometime before the 15th of June.'

'That won't help you. This is Foreign Office business, and my uncle would have nothing to do with it. Besides, you'd never convince him. No, I have a better idea. I'll write to the Secretary at the Foreign Office. He's my godfather. What do you want?'

He sat down at a table and wrote what I said. The plan was that a man called Twisdon (I chose to keep that name) would come before June 15th.

He would be whistling a popular tune and would mention 'Black Stone', and the godfather needed to hear his story.

'Good,' said Sir Harry. 'By the way, you'll find my godfather, his name's Sir Walter Bullivant, at his country cottage in Whitsuntide. Now, what's the next thing?'

'You're about my size. Give me the oldest suit you've got. Then show me a map of the neighborhood. Lastly, if the police come looking for me, just show them the car in the stream. If the other fellows come, tell them I went south after your meeting.'

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «Литрес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на Литрес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Примечания

1

Сити – район Лондона, исторический центр города.

2

зд. старая добрая Англия

3

Булавайо – крупный город в Зимбабве, в Африке.

4

Шотландия является частью Великобритании.

5

Пятизвёздочный отель в Лондоне.

6

заставило меня вздрогнуть

7

Не могли бы вы мне кое в чём помочь?

8

Получается так, что я сейчас мёртв.

9

хотел докопаться до сути