Полная версия

Indo-European ornamental complexes and their analogs in the cultures of Eurasia

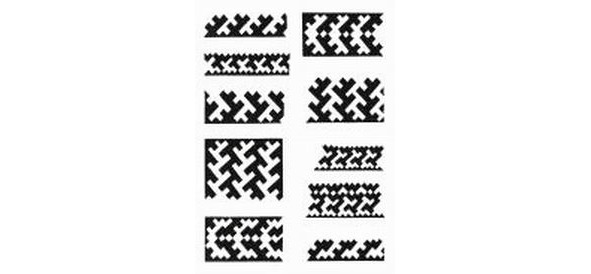

Turning again to the idea of S. V. Ivanov about the uniqueness of ornamental complexes, that “the tribes or groups of tribes that developed them retain the motives included in the complex for a long time,“and even losing connection with each other, continue to keep communities of these groups”, in our case, we can conclude that the ornamentation of the Andronov ceramics of the 17—11th century BC is likely to be related. and decor of North Russian branded weaving, embroidery and lace of the late 19th – early 20th century. To answer the question of how the tradition could have been preserved for at least 3500 years with practically no changes, it is necessary to find out which ethnic groups were carriers of this tradition throughout this time. Since in science there is a widespread opinion that there were rather long and ancient ties between the Indo-Iranian and Finno-Ugric areas, and, in addition, the north of the European part of the USSR, as a rule, is considered as the territory inhabited by the time the Slavs arrived here in the 1st millennium AD. By the Finno-Ugric groups, it is natural to assume that the bearers of the Andronov ornamental tradition were precisely the Finno-Ugrians, who adopted it in ancient times from the Indo-Iranians and preserved it until the end of the 1st millennium AD. It is assumed that most of this Finno-Ugric massif was assimilated by the Slavs, but, nevertheless, peoples such as Karelians, Vepsians and Komi continue to live among the Russian population, not dissolving in it, preserving the language and ethnic traditions.

Ornament is not the last among these traditions. Thus, if the Andronovo ornamental complexes were preserved precisely by the Finno-Ugric population of the north of the European part of the USSR, then these complexes must be constantly present, and in their ancient forms – archetypes, in the weaving and embroidery of these peoples. However, analyzing the patterns of their textiles, we find only a few motifs typical for the decor of Andronov ceramics. Moreover, as G. N. Klimova notes: “in the textiles of the Komi peoples, later features are most widely represented”. In addition, she points to the fact that the development of the art of typesetting weaving in the late 19th and early 20th centuries was characteristic of the western groups of the Komi-Zyryans and the northern Komi-Permians, i.e. those areas where contact with the Russian population was most intense. “In the rest of the territory, with a few exceptions, it was not practiced, and it is difficult to admit that it existed before, because there are neither people nor the memory of the local population about them,” notes G. N. Klimova. And then the researcher writes: “In the areas where typesetting weaving is spread, a number of facts indicate a relatively short period of this technique’s existence there… older women claim that in their villages red patterns began to spread abundantly only at the end of the 19th century. Fashion swept over everyone, and for there was not enough time for all women to master the basis of fashion”.

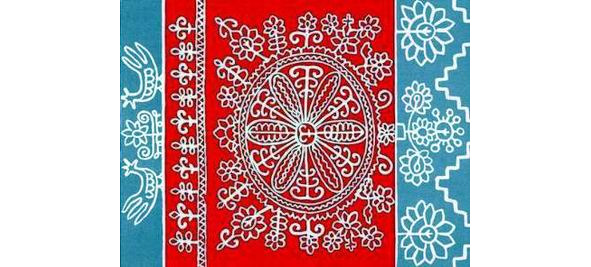

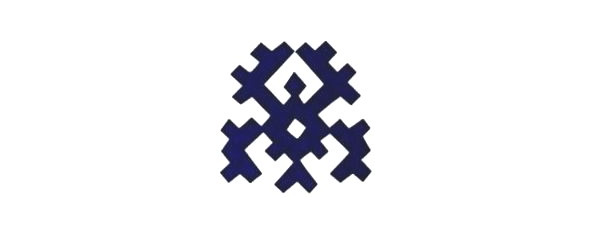

Vepsian ornaments

A. P. Kosmenko, speaking about the art of the Vepsians – settled in the north-eastern part of the Leningrad region, as well as in the north-west of the Vologda region, notes that at the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century, patterned weaving among the Vepsians was significantly inferior to the art of embroidery. She connects this with the fact that the patterned fabrics among them, in contrast to the Russians, “functioned poorly as objects of decorative design of the dwelling”. Further, A. P. Kosmenko writes that: “Vepsians have just started to get acquainted with labor-consuming and difficult-to-make patterns in two-day weaving on a large number of boards at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries… which was largely facilitated by red and white borders for decorative design of towels imported here from the Russians of the Vologda region, where this type of weaving was very developed”. Unlike Russian branched spacers, which had complex ornamental designs and high technique of execution, which testifies to the ancient tradition, the ornaments of Veps weaving items are simple, and the flooring of red threads forming patterns is not complicated, giving the impression of a factory product, like in Russians, but loose, which indicates a lack of technical development and the absence of deep traditions. A. P. Kosmenko notes that: “the red-and-white typesetting technique is not fixed in the weaving industry”, and further makes the following conclusion: “The Veps patterned weaving of the 19th and early 20th centuries does not apply such characteristics as"very developed”, types of decorative weaving prevail”, “more widespread than embroidery, or the same”. But all these characteristics exactly correspond to the level of development of typesetting weaving in the folk arts and crafts of the North Russian population in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

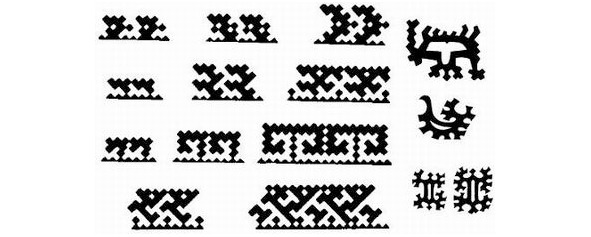

In his other work devoted to the folk art of the Karelians, A. I. Kosmenko writes that, despite the very high level of development of typesetting weaving in them, there is reason to believe that this type of weaving “is not as ancient as, for example, certain types of Karelian The ways of its distribution, obviously, are connected with more southern territories. Typesetting weaving prevailed in the regions of the most intensive contacts with the neighboring Russian population, – in southern and central Karelia. And finally, the Album of Khanty Ornaments (Eastern Group), compiled by N. V. Lukina based on museum collections and field materials of the author, is of some interest. The album contains about 900 ornaments made on birch bark and using the technique of fur mosaic. N. V. Lukina notes that embroidery with threads on fabric is more characteristic of the southern Khanty and now it is rarely found on tobacco pouches, handbags and cult objects, “woven patterns are very rare – on belts and garters of shoes”. Among the 900 ornaments listed in the album, very few have analogues in the North Russian brane weaving. These are “sart-pyonk” (pike teeth) and “tegor-pel” (hare ears) carved on birch bark, as well as patterns consisting of hooks and swastika forms (p. 178 (2) 0, 182 (5), 183 (3a), 208 (1,2,3b), 213 (Ia), 224 (2,3) Thus, only a little more than ten of 900 traditional Khanty ornaments can be correlated with the North Russian ones, i.e. almost a little more than 1 percent.

Khanty ornaments

.

All of the above facts do not allow us to accept the hypothesis that the traditions of the Andronovo ornamental complexes came to the North Russian brane weaving from the Finno-Ugric population of the European north, who allegedly adopted them in ancient times from their Indo-Iranian neighbors.

Other options for resolving the issue of possible carriers of the ancient Andronov ornamental tradition are as follows:

The first is that the substrate population of the European North of our country before the arrival of the Slavs here was largely represented by the descendants of Indo-Iranian groups, as evidenced by the extremely archaic Indo-Iranian topo- and, especially, hydronymy of many regions of the Russian North. Being a substratum of the North Russian group of the Russian ethnos, they have preserved the ancient ornaments of their ancestors.

Second, since the Aryan population of the European part of Russia took part in the process of ethnogenesis of the Eastern Slavs, which did not participate in the movements of the Aryans in the middle of the 2nd – early 1st millennium BC tothe south and southeast, and did not leave these territories, then it is likely that the Andronovo ornamental complexes were also brought to the European north by the Slavs who came here.

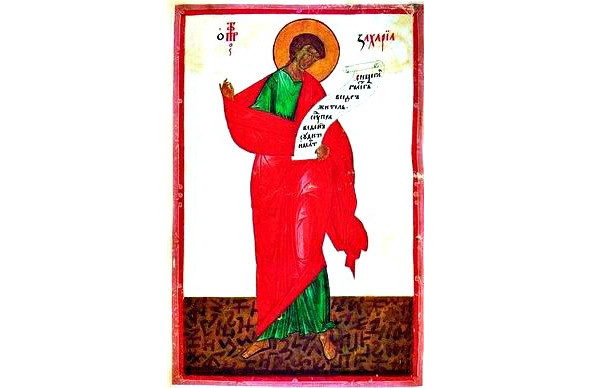

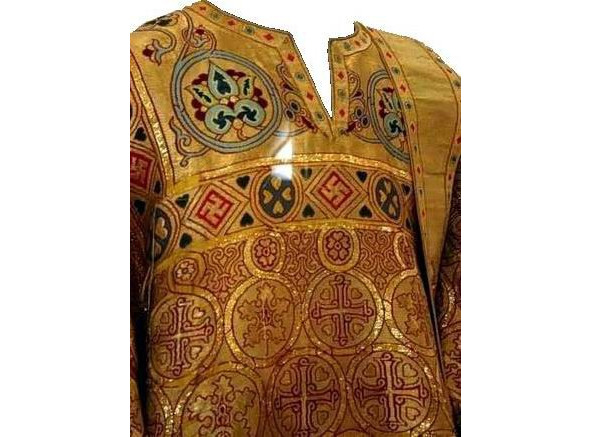

This is all the more likely that Andronovo-type ornaments are characteristic not only for typesetting weaving of North Russian peasant women, but are often found in embroidery, lace and typesetting in other Russian provinces of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. In addition, we can trace the existence of the Andronovo type ornament in the Russian, and more broadly, the East Slavic, tradition over many centuries. So G. N. Klimova, speaking about the traditions of the ancient geometric pattern, notes that they are “present” in the ornament of Russian gold embroidery of the 15—17 century, i.e. there is a stability of patterns of this type in Russia in the past four to five centuries. There is information that lowers their age to the 11—13th century”. Here it makes sense to refer to the materials published by N. A. Mayasova. Without much effort, you can see that most of the attire of the characters depicted in the facial sewing of medieval Russia is filled with rhombic, zigzag and meander patterns. So the meander braid fills the halos of the Mother of God and the saints on the shroud “The Appearance of Our Lady to Sergius” of the second half of the 15th century, the halos of Nikola and Nikola Mozhaisky on the shroud of the early 16th century, it adorns the robes of John the Baptist on the banner of the last quarter of the 16th century and the omophorion of Metropolitan Jonah in the 17th century sewing. Meander braids, rhombuses, crosses fill the clothes of the characters, architectural structures, and even manure on the veil of “Nikola with a Life” of the second half of the 17th century. It should be noted that it is on the last veil in the filling of some details – the clothes of Nikola and the walls of the temples – that the ancient Paleolithic rhomboeander ornament of the Mezin type is presented in its pure form. In the composition “Presenting the Tsarina” 1602 on the robe of the Mother of God are intricately drawn swastikas (Table 7), and on the shroud “Position in the Tomb” ornaments of the Andronovo type adorn the garments of angels, the Mother of God and even a horizontal stripe over the body of Christ. The background of one of the most ancient monuments of Russian facial sewing – the altar shroud of the 12th century made in Novgorod – is all filled with circles of “jibs”, a characteristic motif of Andronov’s ornamentation (Table 5). Not only in sewing, but also in other types of medieval Russian art, we find elements of the ancient Andronovo ornament. So on the ground of the 15th century miniature depicting the prophet Zechariah, made in Moscow, among the various signs are visible “jibs”, swastikas and various swastikas (Table 8). An interesting ornamental composition is presented on a slate spindle, found in a Slavic rural settlement of the 11—13th century near the city of Ryazan, in the area of the Pronskaya SDPP reservoir. On it we see an image that vaguely resembles an Orthodox cross and a human figure at the same time, because the upper and lateral ends of the cross end in tridents, very similar to the three-fingered hands, characteristic of the characters of the sacred circle since the time of Tripoli. This central link in the composition is surrounded by segments of meander spirals and swastikas (Table 9).

Smolensk hallmarks

15th century thumbnail the prophet Zechariah

Omofor

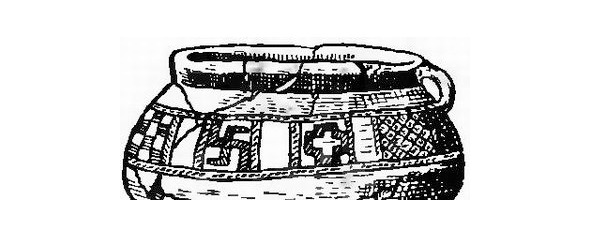

Motifs from simple and intricately drawn swastikas are placed as hallmarks on the bottoms of 11—12th century vessels found during excavations in Staraya Ryazan (Table 9).

Among the marks on the vessels of Smolensk (11—10th century), E.V. Kamenetskaya distinguishes, as the most archaic, the marks in the form of a swastika found on ceramics of the 10—11th century, and believes that they were cult among the Slavs, expressing deification and veneration of the sky, heavenly bodies and fire (Table 9).

Mosaic of St. Sophia Cathedral in Kiev

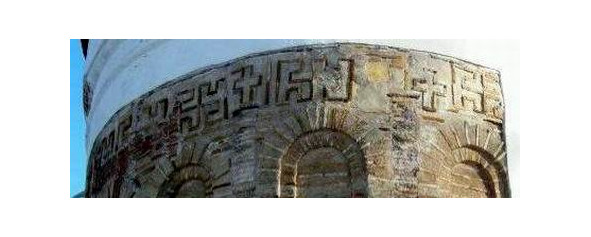

The swastika, as an element of decor, is found in brickwork and mosaics of the first Christian cathedrals of Kievan Rus. This is the main motive of the ornamental belt of the Eucharist composition of the apse mosaic of St. Sophia Cathedral in Kiev (11th century).

Of exceptional interest is the ornamental layout, which decorated the staircase tower of the Spassky Cathedral in Chernigov, one of the oldest structures in medieval Russia, the same age as the Kiev Sophia Cathedral (11th century). N.V. Kholostenko, who published these decorative displays, discovered after the removal of the late plaster, believes that such ornaments had a “special, symbolic meaning.” He notes that the particularly rich decoration of the staircase tower, distinguishing it from other parts of the cathedral, is due to the fact that it was the place of “the ritual entrance of the prince and his entourage to the choir.” (Table 10). In the second tier of the tower, there is a wide ornamental belt made up of alternating equal-pointed crosses and intricately drawn swastikas.

Spassky Cathedral Tower in Chernihov

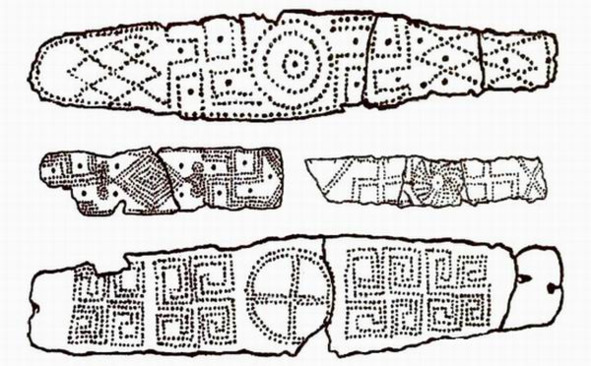

This shape of the swastika, with the ends curving in the form of a meander, was also given to the metal buckle 1220—1260, found at the Tikhvin excavation site in Novgorod (Table 10). It should be noted that this unusual and rather complex form comes unchanged until the 1910s, when a Vologda peasant woman Ulyana Terebova, making an abusive spacer for her daughter’s wedding towel (Table 10), ornamented it with just such meander crosses. Bone combs of the 9—10th century found in the burial mounds of the Suzdal Opolye and in the the lower layers of Staraya Ladoga. The swastika sign marks a clay spindle from a 7—8 century settlement on the Tyasmin River, which belongs to the ancient Slavic tribe of Ulitsy (Table 9).

Spindle

Sinking further into the depths of the centuries, we find all the same meander and swastika motifs in the decor of the products of the Przeworsk and Zarubintsy cultures, which were widespread in the 3rd century BC. – 3rd century AD (according to B. A. Rybakov) in the same territories as the Proto-Slavic Trzhinets and Komarov cultures in the 15—12 century BC.

Przeworsk ceramics

This is well illustrated by the materials presented in the work of A. L. Mongait, which shows various vessels of the Przewor culture, decorated with meanders and intricately drawn swastikas, and in the article by E. A. Symonovich, which also gives samples of meander-swastika decor (Table 11).

E. A. Symonovich in his work notes that the swastika, found on the vessels of the Bronze Age, “is widespread in purely Slavic patterns of the era of Kievan Rus, denoting the sign of the sun”.

And, finally, if we turn to the Scythian period on the territory of the Middle Dnieper region, which proceeded the time of the appearance of the Przhevorsk and Zarubinets cultures, then we will meet the same picture here. On vessels from the Dnieper forest-steppe, one of the most common ornamental-symbolic motifs was a swastika, both of a simple form and of a very complex pattern, with many hooks-appendages at the ends. Moreover, it is extremely interesting that one of the vessels of the 6th century BC from the excavations near the village of Aksyutintsy, next to an equal-pointed cross and swastikas of various shapes, a cross, significantly larger than their size, was placed, which from the beginning of the 2nd millennium AD will become an “Orthodox” cross in Russia (Table 11).

Thus, a continuous ornamental tradition can be traced, going from the cultures of the Bronze Age to Russian peasant embroidery and weaving of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. But since it is in North Russian weaving that the ancient Andronovo complexes are found in the most complete form, which the Finno-Ugric peoples of this region do not have, we can assume another solution to the issue of the carriers of the Andronov ornamental tradition.

It is possible that both the substratum population of the north of Eastern Europe before the arrival of the Slavs here, and the Slavs who came to these lands had similar sacral ornamental symbols, transmitted to them by their distant common ancestors. There was probably a certain awareness of this relationship.

Otherwise, it is extremely difficult to explain the clear direction of the mobile Slavs precisely in Zavolochye, to the East of the European North, noted by V. V. Pimenov in his work “Vepsa”, where he writes, that: “for some not entirely clear reasons, the bulk of Russian immigrants either, like the Novgorod ushkuyniks, passed away, almost without lingering and almost without settling, the indigenous lands of the Vepsians, or else she bypassed them altogether, directing her way directly to Zavolochye”, those on the land of the legendary “chudi white-eyed”, about which we spoke a little earlier.

It probably makes sense to agree with V. N. Danilenko, who expanded the zone of accommodation of Indo-Europeans in the 8—5 thousand BC from the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea up to the watershed of the rivers of the White and Caspian Seas and further north, and assume that the substrate population of the Vologda lands, before the arrival of the Slavs here, was overwhelmingly represented by the descendants of this ancient Indo-European massif. Thus, it will be possible to explain the preservation in the North Russian tradition of such forms, which are completely uncharacteristic of the Finno-Ugric ornamentation, or are extremely rare in it, but at the same time they are constantly present in weaving and embroidery of the late 19th – early 20th centuries of the eastern regions of the Vologda region, on the one hand, and in the monuments of various archaeological cultures of the southern Russian steppe and forest-steppe, on the other. Ornamental complexes, identical to the North Russian ones, typical for the North Caucasus and some regions of the Transcaucasia, they are quite common in the mosaic decoration of medieval temples, mausoleums, mazars of Central Asia and Iran, those common in those territories which modern science associates with the Aryan advances of the late 2nd – early 1st millennium BC.

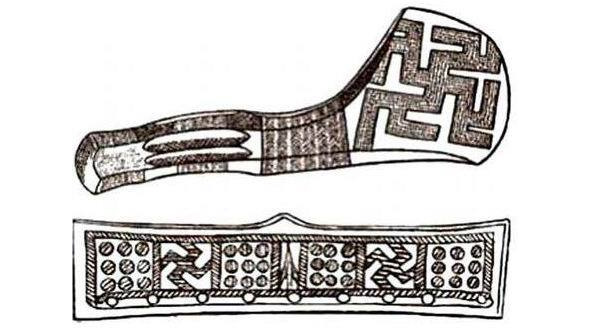

In the Bronze and Early Iron Age, the closest analogues of the Timber-Abashevo-Andronovo ornaments in the southeast of the European part of the country are found in the monuments of the North Caucasus of the second half of the 2nd – early 2nd millennium BC. These are, in particular, materials published by V. I. Markovin from excavations of the crypt of the 2nd millennium BC the village of Engikal in Ingushetia: plaques and pins with disc-shaped pommels, covered with punson swastika and meander-like images (Table 12). He notes that: “unfortunately, the North Caucasian ceramics of the Bronze Age has been poorly studied so far, almost no comparison has been made with the ceramics of the steppe cultures”, and at the same time: “… there is no doubt that it was the steppe tribes of the Lower Don that wedged themselves into the Kuban region”. Here we should once again recall the hypothesis of O.N. Trubachev that the Kuban people of the Sindi are a relic of the Indian tribes that remained in Eastern Europe after part of the Indo-Iranians (Aryans) left this territory. Among the materials published by R. M. Munchaev on the burials of the Lugovoy burial ground in the Assinsky gorge (Checheno-Ingushetia), a significant percentage of double-oval bronze plaques (it is interesting that the same form is characteristic of Slavic brooches of the 8th century), marked with a swastika, punched in the center of each oval. R. M. Munchaev notes that: “… they were always near the skull or chest.

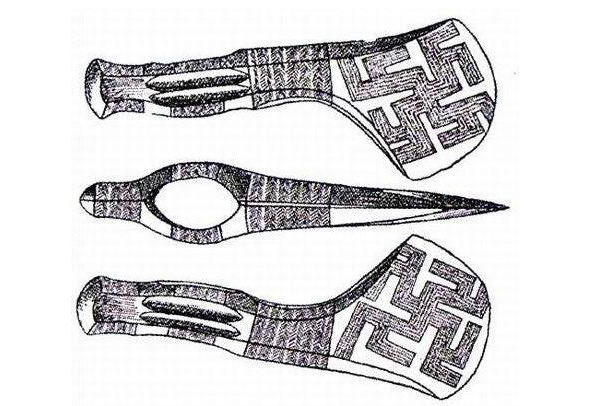

This allows us to consider them as forehead or breast plates”. Interestingly, burial grounds such as Lugovoy and Nesterovsky, also located in the Assinsky gorge, are characterized by the erection of burial mounds over burials. All this is very similar to the traditions of the Andronovites, as well as the obligatory presence in the burials of vessels and ornaments, and on the latter, as we can see, ornamental motifs were placed, more than traditional for the Andronovo monuments. Similar functions of amulets as double-oval plaques from the Lugovoy burial ground, plaques and pins from Engikal, were probably performed by the forehead corollas-diadems of the 14—13th century BC, found by B. V. Tekhov during excavations of the Tli burial ground in South Ossetia. These tiaras are decorated with geometric shapes – circles, triangles, rhombuses, and, as a rule, meander and swastika images (Table 12). B. V. Tekhov notes that similar diadems were found in one of the Styrfaz cromlechs (North Caucasus), in the village. Gegharot (Armenia), on the territory of Azerbaijan and Iran. It is interesting that the continuous pattern formed by swastikas on some diadems (Table 11) is absolutely identical to the ornamental motif characteristic of the Slavic Przewor culture of the 3rd century BC. – 3rd century AD (Table 11) and repeated on a Russian tile of the 18th century (Table 11). The meander and swastika motifs on the bronze axes of the Koban type from the same Tli burial ground are also of exceptional interest. Intricate swastikas placed on these axes from the 12th-9th century BC have analogues in the ornamentation of Pozdnyakovsk vessels, culture of closely related and simultaneous Andronovo.

Koban ornament

Koban ornament

For example, a swastika with numerous “shoots” at the ends, placed on the bottom of one of the clay pots found in the Pozdnyakovsky burial ground “Fefelova Bora” (Ryazan) (Table 12), is repeated with each line on Koban bronze axes (Table 13). But we see such precisely complexly drawn swastikas on one of the maces of the crypt near the villages. Engikal (Table 12), they are present in the ornamentation of finds from a number of places in Azerbaijan, for example, on a clay stamp, as well as on the walls of the temple, the plaster of the dugout and the pintadere (Table 12), on the wall near the hearth and pintadera of the village of Babadervish (Table 1. 12). The same intricate swastika adorns the Koban buckle of the 6—5th century BC (Table 12) and a Scythian vessel from the 6th century BC from the village of Aksyutintsy on the forest-steppe left bank of the Dnieper (Table 12). The most complex swastika braid, carefully crafted by a master of the 9—7th century BC on one of the Koban bronze axes (Table 7), without the slightest changes, it is repeated in the Russian facial embroidery – the pattern of the royal robes of the Mother of God of the above-mentioned composition “Appearing the Tsarina” (Table 7) and in the embroidery of the Olonets valance of the 19th century (Table 7).