Полная версия

Indo-European ornamental complexes and their analogs in the cultures of Eurasia

Indo-European ornamental complexes and their analogs in the cultures of Eurasia

S. V. Zharnikova

Translator Алексей Германович Виноградов

Editor Алексей Германович Виноградов

Illustrator Алексей Германович Виноградов

© S. V. Zharnikova, 2025

© Алексей Германович Виноградов, translation, 2025

© Алексей Германович Виноградов, illustrations, 2025

ISBN 978-5-0065-4859-6

Created with Ridero smart publishing system

The book of outstanding researchers S. V. Zharnikova is devoted to the study of the ancestral home of the Indo-European peoples: Indian, Iranian, Slavic, Baltic, German, Celtic, Romance, Albanian, Armenian and Greek language groups. Part Four of this huge work is devoted to the ornamental complexes of the Indo-Europeans.

Перевод осуществлен Виноградовым А. Г.

Иллюстрации взяты из издания книги “Орнаментальные комплексы индоевропейцев и их аналоги в культурах Евразии” на русском языке.

Translation by A.G. Vinogradov The illustrations are taken from the Russian edition of the book “Орнаментальные комплексы индоевропейцев и их аналоги в культурах Евразии”.

Introduction

In the modern world, the urgency of the problems of the ethnic history of the peoples of various regions of our planet is obvious. The growth of ethnic self-awareness, which has been observed everywhere in recent decades, is accompanied by an increase in interest in the historical past of peoples, in the transformations that each of them experienced in the course of its millennia-old formation. It became a spiritual need for a representative of a modern urbanized society to find the roots of his ethnic existence, to understand the diverse processes that led to the formation of that ethnocultural environment through which he perceives the world around him.

Since the origin and historical existence of the overwhelming majority of the peoples of our planet was associated with numerous migrations, movements to new habitats, causing changes in a number of cultural factors both among the alien people and the indigenous population, today, studying the ethnic history and culture of their people, we, of course, study them in the process of historical transformations and mutual influences of many tribes and peoples, which to one degree or another took part in their formation. Regional ethno-historical research in our time is becoming especially acute, since it is knowledge of the history of one’s own people that helps a modern person to free himself from the narrowness of the nationalist view of the world, to understand the role and significance of the contribution to the common treasury of human culture of all peoples, to realize that humanity is one.

Of course, it is impossible to solve the most difficult issues of ethnic history today without involving data from the most diverse fields of science. It is necessary to combine the efforts of ethnographers, historians, archeologists, linguists, folklorists, anthropologists, art historians, as well as paleobotanists, paleozoologists, paleoclimatologists and geomorphologists, since the development and formation of peoples took place in certain climatic zones, in certain landscapes, with a certain flora and fauna, and this must be taken into account.

Only if the questions posed by ethnic history will be given mutually supportive answers by all of the above branches of science, we can, with a certain amount of confidence, believe that we are close to a true understanding of a particular stage of the historical process. Therefore, at present, the search for an answer to any of the questions of the ethnic history of peoples cannot be considered legitimate without involving data from related sciences.

Part I Geometric ornament of North Russian embroidery and weaving its possible origins and analogues in ancient cultures of Eurasia

1

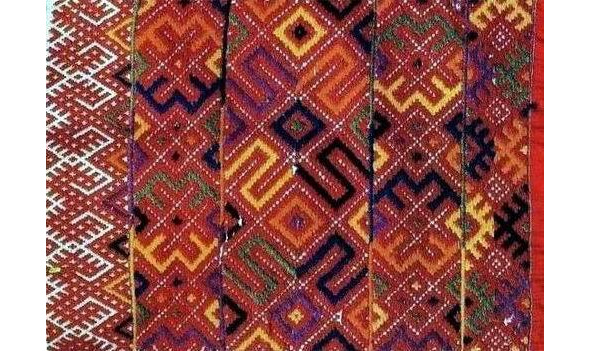

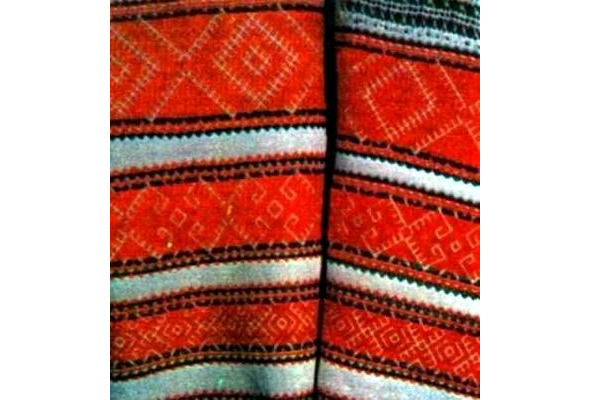

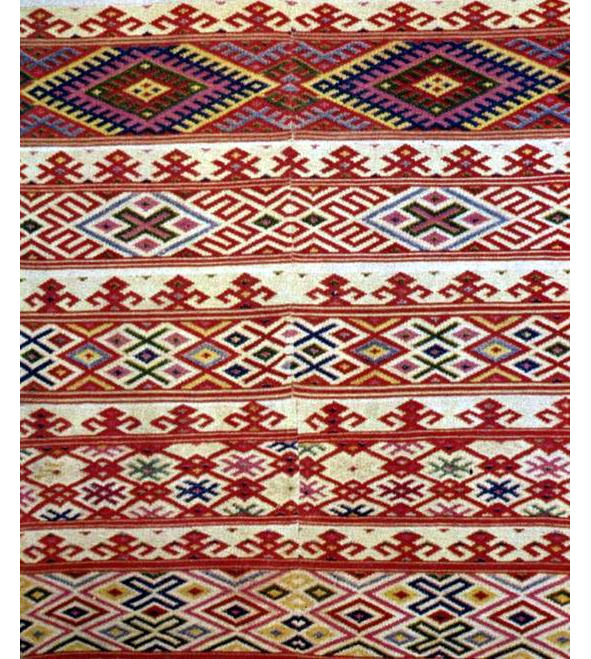

An outstanding researcher of the Russian North A. Zhuravsky wrote in 1911: “In the” childhood “of mankind – the basis for knowledge and direction of the future paths of mankind. In the eras of the” childhood of Russia "– the path to knowledge of Russia, to control knowledge of those historical phenomena of our modernity that it seems to us fatally complex and not subordinate to the ruling will of the people, but the roots, which are simple and elementary, like the initial cell of a complex organism. The embryos of social “evils” are in the personalities of everyone and everyone. the experiences of the grizzled past, and the closer we get to the embryos of this past, the more consciously, more truly and more confidently we will go forward… It is the history of “childhood of mankind”, namely ethnography, that will help us to know the logical laws of natural progress and consciously, and not blindly, go forward and to move our people forward ourselves, for ethnography and history are the ways to know that “past”, without which it is impossible to apply the knowledge of the present to the knowledge of the future. Turning to the millennial depths of the historical memory of the people, we, first of all, will try to reveal, more objectively, those similarities and analogies in the sphere of the spiritual life of the Slavs and Indo-Iranians that go back deep into these millennia. I would like to start the analysis from the works of folk arts and crafts-weaving, embroidery and woodcarving that existed in the Russian North, on the one hand, and similar works of folk art of modern Indo-Iranian peoples, on the other. The connecting thread between these two regions, so remote today, will be that numerous archaeological materials, starting from the Upper Paleolithic period and ending with the developed Middle Ages, from the vast territories of Eurasia, which modern historical science has. The basis for such comparisons is that ethnographic materials, in particular abusive weaving, embroidery, and woodcarving, which existed in the Vologda and Arkhangelsk provinces until the beginning of the 20th century, indicate the preservation, albeit in a relict form, of the memory of ancient Slavic-Indo-Iranian contacts, or rather – kinship. Analogies of ornamental compositions characteristic of the mentioned types of folk applied art can be found, on the one hand, in the extreme south of the Slavic area: in Bulgaria, Yugoslavia, as well as in Western Ukraine and the Dnieper. On the other hand, such ornamental complexes are characteristic of the folk art of Ossetians, mountain Balkarians, Armenians, Tajiks of the Pamirs, Nuristanis of Afghanistan, the peoples of North India and Iran. In addition, as noted earlier, the specific hydronyms, dialectological archaisms present in the Russian North, have numerous analogies in Yugoslavia, Bulgaria, Western Ukraine and the Dnieper, on the one hand, and in Central, South-West and South Asia, on the other.

The Russian North owes such a good preservation of the deeply archaic elements of traditional folk culture to a number of historical reasons. First of all, it should be borne in mind that Christianity came to these parts quite late. So, around 1260, the chronicler of the Spaso-Kamenny Monastery testified that: “you don’t receive the holy baptism, but you don’t open many many unfaithful people to Kubensky.”

It is interesting that even in the second half of the 19th century, in such counties as Ustyuzhsky, Nikolsky, Solvychegodsky, which occupy most of the province, there were one Church in 150—200 populated areas. To a considerable degree, the relics of pre-Christian beliefs, and therefore traditional folk culture, were well preserved due to the fact that here, in the Russian North, there were no sharp ethnic shifts and the associated population changes, practically no wave of conquerors reached here, here there were devastating wars. Most of the Russian North did not know serfdom, and the peasants were personally free, and as a result of this, both the institution of the traditional peasant community and the ancient ritual-ritual practice were preserved for a very long time.

We can assume that the preservation of the elements of folk culture in the Russian North in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, often archaic not only of the ancient Greek, but also recorded in the Vedas, is due to the fact that the population of these places was largely descendants of the ancient population, formed here as a result of advances until the Bronze Age, a time when, perhaps, many social structures, mythological schemes, and those ornamental forms that were common to the vast Slavic-Indo-Iranian region and were preserved in relict form until our days. V. V. Stasov, a well-known researcher of Russian culture, wrote about such relic ornamental forms: “In the ornament of Russian embroidery are precious and as yet untouched materials for studying different sides of ancient Russian nationality.” Indeed, for more than a century, Russian embroidery and abusive weaving have attracted the closest attention of researchers. At the end of the last century, a number of brilliant collections of works of these types of folk art were formed. The studies of V. V. Stasov, S. N. Shakhovskaya, V. Ya. Sidomon-Eristova and N. P. Shabelskaya laid the foundation for the systematization and classification of various types of Russian textile ornaments; they also made the first attempts to read complex “plot” compositions especially characteristic of the folk tradition of the Russian North.

The sharp rise in interest in folk art in the 20th century brought to life a whole series of works devoted to the analysis of subject-symbolic language, technical features, and regional differences in Russian folk embroidery and weaving. However, most of the works focused on anthropomorphic and zoomorphic images, archaic three-part compositions, which include a stylized and transformed image of a female (more often) or male (less often) pre-Christian deity. It is this group of plots that has so far caused the greatest interest among researchers. The geometric motifs of the North Russian branded weaving, as a rule, accompanying the main detailed plot compositions, are somewhat different, although very often in the design of towels, belts, hem, sleeve and mantle shirts it is the geometric motifs that are the main and only than they are extremely important for researchers.

I must say that, along with the consideration of complex plot schemes, serious attention was paid to the geometric layer, as the most archaic in Russian embroidery, in the well-known articles of A. K. Ambrose. In the fundamental monograph by G. S. Maslova, published in 1978, the problem of the development and transformation of geometric ornaments is widely considered from the standpoint of its historical and ethnographic parallels, but, unfortunately, do not go deeper than the beginning of the 1st millennium AD. B. A. Rybakov paid and pays exceptionally great attention to archaic geometrism in Russian ornamental creativity. And in his works of 60—70 and in studies on paganism of the ancient Slavs and Ancient Russia published in 1981 and 1987, the idea of the endless depths of folk memory that preserves and carries through the centuries in images of embroidery, weaving, painting, carving, toys, the oldest worldview patterns, leaving their rooted in the millennia. B. A. Rybakov believes that the origins of many ornamental motifs that survive in Russian art until the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century should be sought in the depths of the Eneolithic and even Paleolithic, i.e. at the dawn of human civilization. Of exceptional interest in this regard are the collections of museums of the Russian North, i.e. those places where the Slavs lived already in the first centuries of our era, long before the baptism of Russia. Remoteness from state centers, relatively peaceful existence (the Vologda region, especially in its eastern part, practically did not know wars), the abundance of forests and the protection of many settlements by swamps and impassability – all contributed to the preservation and preservation of patriarchal forms of life and economy, careful attitude to the faith of the fathers and grandfathers and, as a consequence of this, the preservation of ancient symbols coded in embroidery and weaving ornaments.

Ornament Kostenki

Mezin Ornament

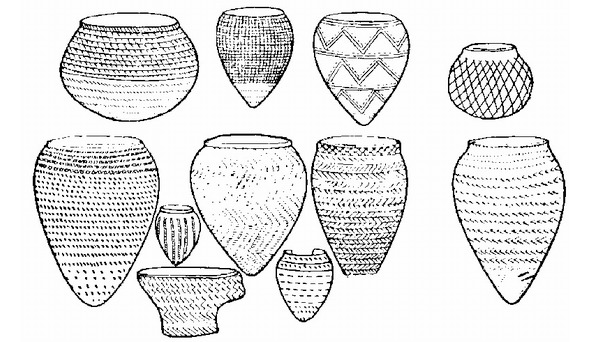

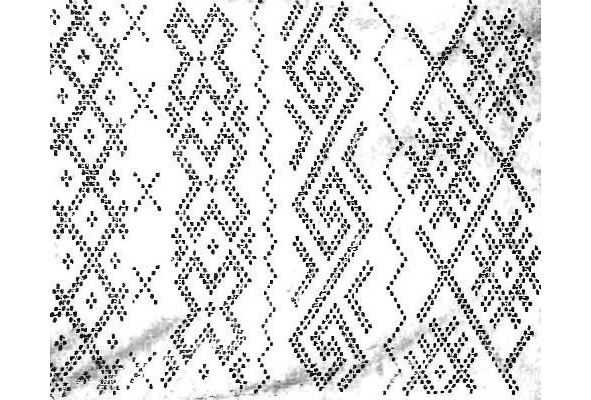

And so, one of the most ancient ornamental motifs of the peoples of Eurasia is a slanting cross, rhombus and meander, appearing for the first time in Eastern Europe (Kostenkovskaya and Mezinskaya cultures) on products from marl, bone and mammoth tusks already during the Upper Paleolithic (26—23 thousand years) ago).

A. A. Formozov notes that already in the Middle Paleolithic (during Mousterian time) there is a big difference between the Mousterian monuments of the Russian Plain and the Caucasus, on the basis of which he considers it possible to talk about the formation of ethnocultural areas on the territory of the European part of the USSR in the Stone Age.

In the Upper Paleolithic, the difference between the southwestern historical and cultural region and the neighboring areas of the Dnieper and Northern Black Sea regions is also noted, despite the fact that researchers emphasize the vast expanses from the upper reaches of the Dnieper basin, the entire Volga basin to the Ural Mountains, which have been studied poorly and, therefore, do conclusions here are not yet possible. One of the most important ethnocultural differentiators, along with the characteristic features of the flint and bone industry, the house-building system, zoo and anthropomorphic sculpture, even at that time, was ornament. So in the II cultural layer Kostenok 14 near Voronezh (abs. Age 26—28 thousand years ago) and in Vladimir Sungir (abs. Age 24—25 thousand years ago), dating from the early Upper Paleolithic, were found made in a certain stylized ornamented bone products and mammoth tusk. Researchers note: “their carved geometric and dimpled ornaments are preserved and developed in the subsequent heyday of the Late Paleolithic cultures of the Russian Plain.” Analyzing the ornaments of the last stages of the Kostenkov culture M. D. Gvozdover comes to the conclusion that: “the oblique cross is most often found from the elements of the ornament… Obviously, this ornament should be considered the most characteristic for the Kostenkov culture, especially since in other Paleolithic cultures the ranks from oblique crosses are almost unknown. “She further notes that the choice of ornament and its location on the subject is not due to technological reasons or material, since the same ornament was applied to a flat and convex surface, to a tusk, bone or marl, but to cultural tradition. Thus, already at this early stage in the history of human civilization, “the archaeological culture is characterized by both the elements of the ornament itself and the type of arrangement on the ornamental field and the grouping of elements.” The rows of oblique crosses that first appeared on the products of the Kostenkov culture did not disappear along with the cultural tradition that gave rise to them. We can trace these signs on the monuments of different, successive, archaeological cultures of Eurasia. They are found on Neolithic ceramics, on the products of Trypillian potters, on the vessels of the Afanasyevsky, Yamnaya, Srubnaya, and Kushetin-Komarov cultures.

Neolithic pottery

Tripolie ceramics

Tripolie ceramics

Pottery of Afanasyev culture

Pit culture pottery

Ceramics of the “carcass” culture

As they obstructed the oblique cross on the bottoms of clay Slavic plates, they marked the sculptures indicating the path to the top of the sacred Sobutka Mountain near Wroclaw in Silesia, created no later than 5th century AD, they were placed on the ceramics of Kievan Rus, and until the end 19 century the North Russian peasants decorated the ends of the spinner’s claws with these rows of oblique crosses.

It is difficult to find in the Russian North an instrument of peasant labor made of wood – whether it be a spinning wheel, sewing machine, flax, a wooden stand for a sunflower, on which a slanting cross or a number of such crosses as a single ornamental motif would not be cut or scratched anywhere oblique crosses are quite often found on the woven spacers of the North Russian peasant women.

All this testifies to the fact that ornamental complexes and signs that have developed even in the depths of the Paleolithic survive almost unchanged almost to the present day, and, passing through millennia, they do not lose their main meaning – a sacred sign, because what else can explain the cutting of an oblique cross under the bottom of the spinning wheel, on the handle flax, the cutting of a number of oblique crosses on the lapaska’s torn where no one sees them in general, or the presence of only oblique crosses on a branded spacer sewn to a holiday towel or hem smart women’s shirt.

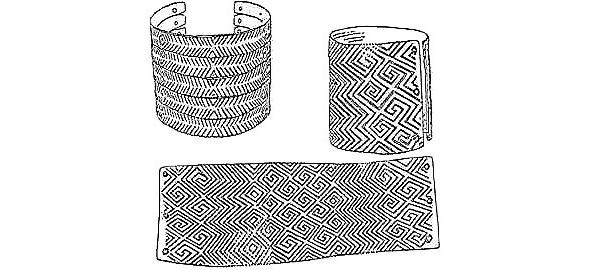

Weaving. Olonets

Weaving. Totma

Weaving. Solvychegodsk

Weaving. Kargopol

Weaving. Kargopol

Weaving. Kargopol

Weaving. Pineega

Weaving. Dvina

Weaving. Dvina

Weaving. Tver

Weaving. Tambov

Weaving. Dnieper

3

The next group of the oldest ornamental motifs on the territory of the European part of our country is represented by a rhombus and rhombic meander, first appearing on products from mammoth tusks originating from the Mezinsky Late Paleolithic site in the Chernihiv region. As noted earlier, paleontologist V.

Bibikova in 1965 suggested that the meander spiral, torn meander stripes and rhombic meanders on objects from Mezin arose as a repetition of the natural pattern of mammoth tusks of dentin. From this, she concluded that a similar ornament for the people of the Upper Paleolithic was a kind of magical symbol of the mammoth, embodying (as the main object of hunting) their ideas about wealth, power and abundance.

Mezin Ornament

It is the Mezin ornament, which has no direct analogies in the Paleolithic art of Europe, which can be placed “on a par with the perfect geometric ornament of later historical eras, for example, the Neolithic and copper-bronze, in particular, the Tisza and Tripoli cultures.”

Once again, I would like to emphasize that, comparing the Mezinsky ornament with North Russian weaving, V. A. Gorodtsov exclaimed in 1926: “reminiscence (a vivid memory) of the most ancient universal human religious secrets is hidden in the patterns of North Russian skilled craftswomen symbols. And how fresh, what a solid memory!”

The Mesolithic period that followed the Paleolithic remains, until today, a white spot in the history of ornamentation. At this time, the researchers note, there was a widespread transition of the population of Eastern Europe from settledness to a mobile, wandering existence, which is probably due to the disappearance of the mammoth, which was the main object of hunting. Thus, products from tusks and mammoth bones were no longer produced, while ceramics appeared only in the Neolithic. But we have no reason to believe that the Paleolithic ornamental motifs, in particular the meander ornament of the Mezinsky site, disappeared forever. Probably, in the Mesolithic ornamental tradition continued to exist and develop on products made of such materials as leather, birch bark, wood, plant fibers. This is evidenced, for example, by patterns on wooden products of the Mesolithic age (7—6 thousand BC) found in the 1st Visa peatland near Lake Sindor in the Komi Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic. These patterns of zigzags, parallel lines and oblique mesh are repeated without changes then on the Neolithic Kargopol ceramics.

Kargopol ceramics

Only the preservation of the ancient Paleolithic ornamental traditions in the Mesolithic can explain the fact that the Neolithic ceramics of the vast region from the Dnieper to the Balkans and the Northern Caspian Sea have the same meander patterns and their various modifications as on the Mezin bone products (Table 1).

At the many Neolithic sites of Ukraine, one of the most common at that time was a positive-negative meander ornament: fragments of ceramics from the Mitkov and Bazkov islands, from the settlements of Gayvoron-Polizhok, Vladimirovka are decorated, as a rule, with a complex meander pattern (Table 2.3). Published these materials V. N. Danilenko noted that such ornamentation is only partially modified, without disappearing for millennia. He writes: “There is no doubt that such an ornament is preceded by a spiral meander ornament of the later stages of the development of the agricultural Neolithic. At the same time, it is obvious that precisely such ornamental compositions, despite their exceptional antiquity, are already close to Early Tripoli. The last circumstance has to be explained not so much chronological how much ethnocultural proximity of the local early Neolithic with Tripoli.”

B. A. Rybakov, investigating the development paths of the ancient rhombo-meander ornament in the Neolithic, concludes that: “The stability of this complex and difficult-to-implement pattern, its undoubted connection with the ritual sphere makes us treat it especially carefully… Neoenolithic meander and rhombic the pattern turned out to be a middle link between the Paleolithic, where it first appeared, and modern ethnography, which gives innumerable examples of such a pattern in fabrics, embroidery and weaving”. Speaking about the dentin pattern of mammoth tusks, as a possible prototype of the Paleolithic meander-carpet pattern of the Mezin type, B. A. Rybakov notes that: “The amazing durability of exactly the same pattern in the Neolithic, when there were no mammoths anymore, does not allow us to consider this a mere chance coincidence, but forces us to look for intermediary links. I consider the custom of ritual tattooing to be such a mediating link”.