Полная версия

The Paths of Russian Love. Part III – The Torn Age

In the famous novel, Mikhail Bulgakov, as if carried away by his «outlandish» but «truthful narrative,» addresses the readers, taking risks and promising something that no literary man has ever managed before:

Follow me, reader! Who told you that there is no true, faithful, eternal love in the world? May the liar have his vile tongue cut out! Follow me, my reader, and only follow me, and I will show you such love!

So defiantly firmly could risk his professional reputation only someone who, first, experienced true love himself, and secondly, was confident in his literary talent. The love that the author experienced and wanted to tell the world about, happened to Bulgakov with the third woman who became his wife.

Elena Shilovskaya, thirty-five-year-old housewife, wife of a Soviet military commander, mother of two children, who retained a love «for life, for noise, for people, for meetings» and embodies its «unspent strength» only in the «thoughts, fictions and fantasies», met in February 1929 with a dramatist who made a name for himself in theater circles, a man with a «satirical» mind. There was some kind of witchcraft, and they began to meet almost daily, embraced by a «quick love,» while in March from the repertoire of theaters were removed all the plays of Bulgakov, and in July in despair, «driven to a nervous breakdown,» he wrote a letter to Stalin asking for «exile» from the country.

By this time came to naught «comfortable» relationship with his second wife, Lyubov Belozerskaya, who studied ballet, went through emigration, danced in Paris, worked in a Berlin newspaper, where Bulgakov was publishing, and was competent «in the sense of literature,» according to the first wife, Tatiana Lappa, who was used to the «creative» hobbies of her husband and did not expect him to break his promise: «You have nothing to worry about – I will never leave you.» In Belozerskaya he found not only an interesting storyteller about the ordeals of Russian emigrants, life abroad and assistant in publishing worries – «a woman vivacious and industrious», but also «some sort of nice and sweet» woman, so that he found himself in an unexpected state – increasingly in love with his own wife. It is not known what cut short this «terribly silly» feeling, – the occasions for «slight jealousy,» the «exposure» that Lyubov (her name sounds «love’ in Russian) is for the sake of living space, or its destroying: «But you’re not Dostoevsky!» – only the meeting with true love this time was not marred by the bitterness of betrayal and unfulfilled duty.

Mikhail Afanasyevich Bulgakov (1891—1940)

Five years later, when passed the passions of a two-year secret affair and the clarification of relations with her husband, armed with a gun, a forced one-and-a-half-year separation and a new meeting forever, Bulgakov, working on a play about the last days of Pushkin, puts in the mouth of Natalia Nikolaevna not peculiar to that era self-justification:

Why has no one ever asked me if I am happy? They only know how to demand from me. But has anyone ever taken pity on me? What more do you want from me? I gave birth to his children and all my life I hear poems, only poems…

Moreover, to Pushkin’s drama, it turns out, involved completely different forces:

The death of a great citizen was committed because the country’s unlimited power is handed over to unworthy persons who treat the people like slaves…

Unlike Dantes, who, according to the assurances of his adoptive father, «loves no one» and «seeks pleasure,» Bulgakov was truly in love, and the Red Army commander with a generous nobility under the influence of trends about women’s freedom, unlike bretteur Pushkin could afford to let his wife go to another man, since she had «born a serious and deep feeling».

In his phantasmagorical novel, painting a picture of «faithful, eternal love,» Bulgakov solves the Pushkin-Dantes collision by concentrating genius creativity, irresistible passion, and thirst for true love in one character, the Master, and putting out of brackets the events surrounding the fateful meeting with her, adorned with «disturbing yellow flowers,» of both the jealous bretteur and the noble husband. And what would have been different and most necessary in a woman who would have epitomized such love? No, she would not shine with porcelain beauty, as Natalie, but only if in her eyes «always burned some incomprehensible light», and she would need «not a Gothic mansion, and not a separate garden, and not money», but «him, the Master.» The Master as a companion, leading the way in life. Her lover must see another, «resting» life and be one of its earthly creators, even if doomed to a thorny path. Then there will be an unshakable respect for him, an inexhaustible desire to support his work, an inexorable desire to participate in his grand design, and an unwavering willingness to fight for her love.

How can Margarita-Natalie save her high love when through the ages the same «unworthy persons» continue to rule the fate of people? Only by making a deal with those who have much more power, but not there, in the bright world, but here, on the sinful earth. To get back her Master, crushed by critics and denunciations of «good people», Margarita goes to «replace her nature» – becomes a witch. But neither service to Satan at the «great ball» nor revenge on the Master’s offenders are the main feats of the loving Margarita. The strength gained in love allows her not only to «share the fate» of the Master, who hated his novel, which brought only misfortune, filled with fear and cowardice, but also to start thinking for him, assuring «that everything will be dazzlingly good».

However, what does Bulgakov deduce as the ultimate metaphysical goal of faithful love? Is it «an eternal home» with «a Venetian window and curly grapes», silence, and in the evening – music by Schubert, walks «with my friend under cherry trees» and sleep «with a smile on my lips?» Why not, for it looks like a royal gift. But still the main thing is different – love sets the Master free.

Someone was letting the Master go free, just as he himself had just let go of the hero he had created.

What remains to be deciphered is what the Master has freed himself from through the magical power of love. The novel states that «the Master’s memory, the restless, needle-stabbed memory began to fade.» It is known that Pontius Pilate suffered because of his own cowardice, «the most grievous vice,» and this sin was eventually forgiven him. Then for lack of direct evidence, we can only assume what imperfections of his own nature and sins burdened the Master. About himself, Bulgakov said that in the past «made five fatal mistakes4», of which two due to «an attack of unexpected, struck like a faint of timidity.» And he, it must be assumed, would give a lot for «someone» to forgive him these weaknesses of human nature, freeing the restless memory for full happiness in the light of found love.

Let us note one more feature that Bulgakov emphasizes in the bargain with the wicked force to «replace one’s nature» for the sake of love. Margarita retains a mercy uncharacteristic of a witch towards the infanticide Frida and the infamous Pontius Pilate. Her mercy, however, is not pity spewed from a weak soul, but a struggle for her own dignity – responsibility for the one to whom she has given hope. And she knows that he who violates this rule, who drops his dignity, will not «have rest all his life.» In the case of Pontius Pilate, the voice of reason speaks in her, telling her that there is no justice in the punishment of eternal loneliness for once shown cowardice. And the higher powers are coming her way.

«Well, well,» will think some of the novel’s most persistent readers,» what is the Master’s special merit, what justifies his unearthly love and his release from the torments of memory?» Most likely, in the fact that he managed to «guess» what was going on in the soul of Pontius Pilate, when he was forced to make a fatal decision about the fate of the «wandering philosopher», as well as what was needed by the woman, in whose eyes lurked «an unusual, unseen loneliness», and in her hands were «disgusting, disturbing yellow flowers». In this quality – to understand the soul of the person closest to you – lies the main characteristic of true love, because it is a part of divine providence, able even to free from the seemingly most serious sins5.

With his true story of eternal love, reflecting his own third, successful attempt, Bulgakov gives a clear illustration of the analytical observations of the Spanish philosopher José Ortega y Gasset6 over the zigzags of true love, who believed that those who are inherent in «characters restless and generous, characters of inexhaustible possibilities and brilliant destinies,» during life undergo «two or three transformations, the essence of the various phases of a single soul trajectory». And these transformations coincide with the «deep feeling of love» that «embraces any normal man two or three times in his life», and «a new feeling of life corresponds to a new type of woman». It may be noted, however, that to the elegant theoretical constructions of the Spanish philosopher the Russian writer adds the necessity at each «new stage» to release «restless memory» in some way and at a deliberately high price.

Let us note that the unreality of the events described by Bulgakov leads the heroes of the novel to a madhouse. There, the Master tells the bad poet how he met his true love, and the poet, determined to change his life, shares the details of his meeting with Satan. In Bulgakov’s novel it is only an episode, and in other contemporary writers, the attempt to portray high love typically ends either with madness or death of the characters seized by fatal passion, and sometimes brings to a nervous breakdown even the writers themselves.

III

Madness of love. Under the power of a woman. Grammar of love. Picture of first love. Disappearance of time. Compassionate tenderness. Scales of love. Undercurrents. Assemblage of personality. Intolerability of eternal inseparability. Mean-spirited insult. Return to authenticity. Self-deception of love. Compass of love

In 1928, the future Nobel laureate Ivan Bunin published the story The End of Maupassant, where, in connection with the anniversary of the death of the great French novelist, whose final age he had already surpassed by fifteen years, he described his last days in a madhouse. Giving details of the insane behavior of Maupassant – «in his delirium constantly the same thing: murder, persecution, God, death, money…» – Bunin is struck by the fact that «so expressed now he has his former complex, painful thoughts, so many times with such precision, with such beauty and elegance expressed by him!» After familiarizing ourselves with Bulgakov’s novel, we will not find it surprising that Maupassant also sought to exorcise the devil who had climbed into his hospital room.

Bunin found in Maupassant both «excellent» places and «mere trifles,» «vulgar sketches.» but considered him (practically repeating Tolstoy’s phrase7) outstanding in that «he is the only one who dares to say endlessly that human life is all under the power of the thirst of woman». This power, we can assume, also dominated the life and work of Ivan Bunin himself, despite his outwardly solid and firm character.

Ivan Alexeyevich Bunin (1870—1953)

In the story The Grammar of Love we learn about a landowner who was obsessed with love for his maid and sat on his bed for more than twenty years after her death in her early youth, leaving behind a notebook with a moralizing address: «The hearts of those who loved will say to you: Live in sweet legends! And to grandchildren and great-grandchildren they will show This Grammar of Love.» This «grammar», divided into small chapters, contained «sometimes very subtle maxims»:

Our reason contradicts our heart and does not convince it. – Women are never so strong as when they arm themselves with weakness. – Woman we adore because she lords over our dream of the ideal. – Vanity chooses, true love does not. – The beautiful woman must occupy the second step; the first belongs to the lovely woman. This one becomes the ruler of our heart: before we give an account of it to ourselves, our heart is made a slave of love forever…

Let us turn to the creative legacy of Ivan Bunin and see if he managed to add something substantial to the naive grammar of love of a mad landowner and, unlike Maupassant, not to be disappointed in sexual love, in which «great happiness» is inseparable from the «agonizing loneliness,» but to find, according to Leo Tolstoy’s conviction, love «pure, spiritual, divine.»

As if conspiring, in the same fifty-seven years of age and the same in the midst of infatuation with a young woman, Bunin, like Gorky, begins to write his main, largely autobiographical novel The Life of Arsenyev, where he creates a picturesque portrait of the first and truly genuine love, in which from the height of literary and life experience, he reveals the action of its eternal inexorable laws.

At first, the adolescent Arsenyev feels only the first glimpses of «the most incomprehensible of all human feelings» as «something especially sweet and languid.» But in this special feeling arising from «women’s laughing lips,» «the sound of a woman’s voice,» «the roundness of women’s shoulders,» «the thinness of a woman’s waist,» there is already something «terrible,» leading to numbness, so that sometimes he «could not utter a word.» At sixteen, «youthful feelings,» enhanced by the wonderful mysteries of the wedding of his older brother, are embodied in the «happy embarrassment» in the presence of Anchen, the «simple,» «young niece» of the new relatives. And in the young man in love, endowed with a «keen sense of life,» a powerful generator of imagination is set in motion, absorbing the «romantic vignettes» of the poets of the estate library and giving birth to a «thirst to write himself.» After Anchen’s departure, her «living appearance» turned to poetic feeling «with a longing for love in general, for some kind of general beautiful female image.»

Along with the poetic experience of love Arsenyev was filled with «heightened mental structure»: «a sense of his young strength, bodily and mental health, some beauty of the face and great dignity of the constitution,» as well as «consciousness of his youthful purity, noble motives, truthfulness, contempt for any meanness.» This incredible elation of the soul was ready to build new air castles of love, if only from a chance encounter with a fifteen-year-old skinny girl in a gray dress, with «touchingly painful lips.» The new love this time was «unbearably charming» with «the whiteness of her legs in the green grass» and absorbed both the «June scenes» of bathing in the pond, and «the dense green of shady gardens,» and the smells of «fading jasmine and blooming roses.»

Two years later, Arsenyev meets his true love. He, a budding poet already published in «metropolitan monthly magazines,» meets three young pretty women in the editorial office of a provincial magazine, and for some reason his choice falls on Lika, who only looked at him «friendlier and more attentive, spoke more simply and more vividly.» Later, marveling at how quickly the time flew by, he will define the first sign of the «meaningless-fun, like ether intoxication» state of falling in love as «the disappearance of time.»

Varvara Pashchenko, the prototype of Lika, was a girl «quite intelligent and developed,» and in the relationship with her, backed by reciprocal, though fluctuating, as on the scales, feeling and tenderness, guessed a wide palette of common thoughts and aspirations. In a letter to his brother Bunin confessed that he had «never loved so wisely and nobly.» On his scales of love, everything that was found on the negative side was not taken seriously or was considered surmountable. He tried to convey to her his cherished dreams «about the future, about fame, about the happiness of creativity,» to explain that for this he needs to keep «purity and strength of the soul,» and she should avoid the «vulgar» theatrical environment and get rid of «bad tastes and habits.» And although she was with him and «not quite like-minded,» she «still understood a lot.»

In his love for Lika, Arsenyev discovers the action of its «secret law», which requires «that any love, and especially love for a woman, should include a feeling of pity, compassionate tenderness» – he «ardently loved her simplicity, silence, meekness, helplessness, tears, from which her lips immediately swelled childishly.» However, the action of this law is associated with the insidious need to know one’s limits: sometimes a feeling of pity obscures love itself. Lovers may not notice what is striking to friends and relatives. The editor of the Oryol Herald, where Bunin worked, who was involved in the twists and turns of Ivan’s quarrels and reconciliations with Varvara, writes to his older brother that «she is gradually losing both feelings for him, and respect, and trust», that «Pashchenko does not love him, but only pities him… and he will never be happy with her.»

Indeed, Bunin’s beloved had no shortage of reasons for pity. He had not finished his last year of high school, lived like a «vagabond,» had no position in society, could have been drafted into the army, her family was categorically against her marrying a groom «without any means,» literary fame was only a dream, and all of his still unstrengthened creative forces he was striving «to form in himself from what life gave him something truly worthy of writing.» In addition, there was always doubt in her love, it seemed to her that «she did not love the way one should love… not the way they say, the way they write in novels.» A separation for a year did not bring clarity to the «authenticity» of her love, and then, having lived with him in a civil marriage, she left him and got married.

At first glance, there is nothing remarkable in the story of Bunin’s love, except perhaps an amazing belief in himself, his literary talent, a firm desire for a different, «more idealistic life.» At the same time, his «reasonable» love is quite selfish: he «wanted to be loved and to love, remaining free and in everything superior.» Bunin’s alter ego Arsenyev instilled in Lika «one thing: live only for me and by me, do not deprive me of my freedom, my self-will, I love you and for this I will love you even more.» All this sounds strained and pompous, if you do not take into account the deep currents of Bunin’s love.

Bunin’s first true love became a wonderful source of strength and energy for the assembly of his developing personality and for strengthening his faith in the feasibility of his cherished aspirations. It filled with life juices two main features of his nature. One of them was his belonging to an ancient noble family, of which he was proud, therefore he took to heart the command of his ancestors «to guard your blood: to be worthy of your nobility in everything8.» The other was connected with an unyielding desire to follow his inner voice, his own «ideas about something» that cannot be expressed, and this was one of the reasons why his beloved «began to feel lonely.» For example, he wandered a lot and, «returning home on a night train,» frivolously fantasized, looking at the «sleeping on their backs» Ukrainian women with «open lips» and «breasts under their shirts.» At the same time, it seemed to him that «I love her so much that everything is possible for me, everything is forgivable.»

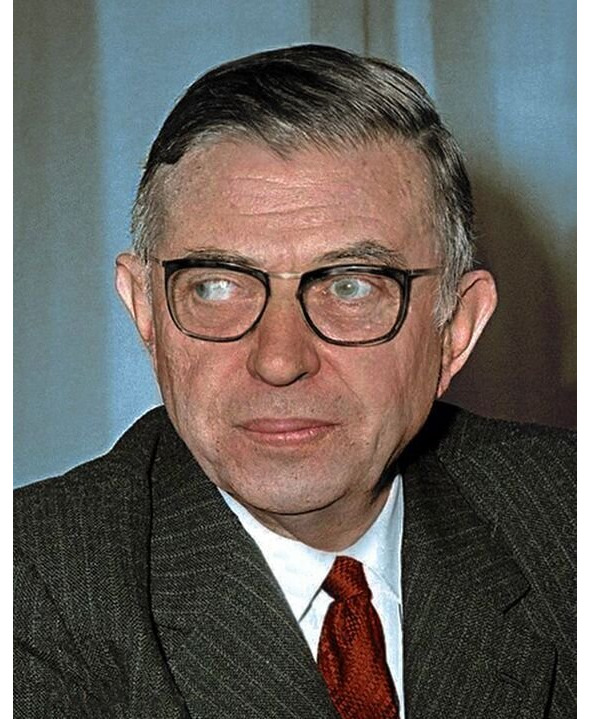

It should be noted another feature of Bunin’s description of his main love. He could not imagine life without her, but at the same time he was perplexed by the possibility of their «eternal inseparability»: «is it really true that we have come together forever and will live like this until old age, will we, like everyone else, have a home, children? The latter – children, a home – seemed especially unbearable to me.» Finding some acceptable solution to such a complex tangle of contradictions for a heart that had «opened up for the first time in its life» was possible only in some new paradigm of love relationships, for example, the one invented for themselves by the young French philosophers Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir, who met at the Sorbonne in 1929.

Jean-Paul Sartre (1905‒1980)

At that time, Bunin, who had emigrated to France after the revolution, married for the second time to a devoted woman who valued his literary mission, the love to whom had become for him «like air: you can’t live without it, but you don’t notice it,» had already been practicing an original model of marriage for three years, including a romantic supplement in the form of a grateful young student of the venerable writer. The participants in these intimate relationships, which quickly turned burdensome, understood its nature differently and intuitively found their own justification. Vera Nikolaevna Muromtseva-Bunina thought with bitterness that «there is no such thing as shared love in life. And the whole drama is that people do not understand this and suffer especially.» She humbly realized that «has no right to prevent» Bunin «to love whom he wants,» that «human happiness is in not wanting anything for yourself.» The position of the young writer Galina Kuznetsova in the Bunin household was unenviable, despite the even, benevolent attitude of the official wife. She «felt hopeless…, lonely as in a desert,» in fear of «a dark future.» After eight years of «a difficult path» and suffering, she would leave the sixty-four-year-old Bunin, falling under the influence of another romantic leader, the singer Margarita Stepun, the sister of the famous philosopher, thereby causing him «a heavy feeling of resentment, vile insult» and «mental illness.»

Fyodor Stepun, who was a friend of Bunin, emphasized that the literary works of the Nobel laureate are distinguished by their authenticity, «the primacy of thoughts and feelings,» that for him «truth is not an abstract idea standing above him, but the blood and flesh of his spiritual-mental-physical being.» Stepun, like other philosophers of the early 20th century, noted the unsettled state of man in modern culture and linked «the exit from the lies and torment of this life-destroying wealth, in which thought is indistinguishable from fiction, will from desires, art from entertainment» with a return to authenticity. The paradoxes of love in The Life of Arsenyev and Mitya’s Love, described by Bunin «with the rare power of creative transformation of earthly appearances and accomplishments of our mortal life,» could serve as a vivid illustration of Sartre’s theorizing about the inevitable contradictions that an individual encounters when striving for a genuine (authentic) existence.

In Sartre’s view, love has two poles of power. On the one hand, love means an attempt to realize an «organic set of projects» generated by an individual’s own capabilities. On the other hand, it is carried out as a «project of unification,» which, being «the ideal of love, its motive and its goal, its own value,» still acts as a source of conflict, since it depends on the changeable freedom of the other. Developing Sartre’s thought, Simone de Beauvoir described the difference in the meaning of love for a man and a woman:

An individual (a man), who is a subject, a personality, who has a noble aspiration for transcendence, does everything to increase his influence on the world, he is ambitious, active… She (a woman) has only one opportunity: to lose herself with her soul and body in the one who is presented to her as an absolute value… But love does not take up so much space in a woman’s real life. Her husband, children, home, pleasures, vanity, social and sexual relations, and social advancement mean much more to her. Almost all women dream of «great love,» some of them touch it, others get a surrogate, they know it as incomplete, flawed, ridiculous, imperfect, false. But very few really devote their entire lives to it.