Полная версия

The Paths of Russian Love. Part III – The Torn Age

The Paths of Russian Love

Part III – The Torn Age

Yury Tomin

Dedicated to my beloved children Egor, Daria, Ilya and Anna

© Yury Tomin, 2025

ISBN 978-5-0065-2980-9 (т. 3)

ISBN 978-5-0060-0978-3

Created with Ridero smart publishing system

PREFACE

In the third part of the book The Paths of Russian Love we will try to find out what new for the understanding of love was given by the seventy-year experiment in the implantation of romantic relationships on the new social soil created in the Land of Soviets. Three vectors of Russian love (romantic, rational and deep), which we found in its Golden – XIX – century, at the turn of the XX century in the Silver Age converged in one key point: an incredibly charged search for ideas, forces and energies for the formation of a new man, able to live, love and create fully and happily. A vivid representative of the main cultural and philosophical current of the Silver Age, Zinaida Gippius believed that the labors of the Symbolists to find the keys to the mysteries of human nature were not in vain, that at the end of the «dark corridors», where they had to descend, «glimmered a white dot.» But the hard-won knowledge remained fragmented, difficult to convey, and accessible only to those «to whom it is time to hear.»

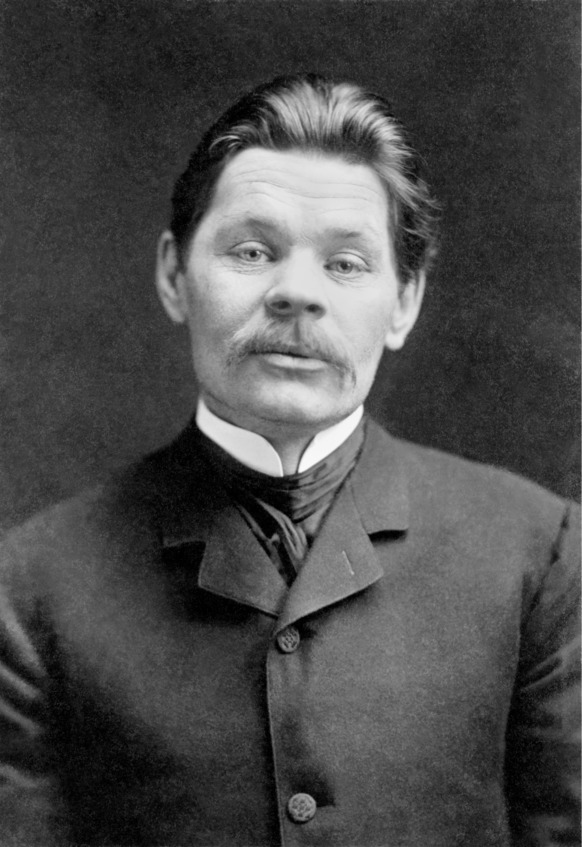

Looking at the deep gap between the Russian Empire and the Soviet country, we would do well to rely on some courageous guide to connect the cultural epochs of the country torn apart by revolution and civil war. It is not easy to find one. Those who, like Alexandra Kollontai, set the tone for radical transformations in love relationships, diverged sharply from both traditional family life and hypocritical bourgeois morality on the sexual issue. Others, like Mikhail Bulgakov, if they touched on this «secondary» issue compared to the class struggle, they resorted to fantastic plots and mythological images. The most suitable for this role is the world-famous writer Maxim Gorky, an indefatigable vagabond, fighter and toiler according to the symbolism of his ancestral surname Peshkov and a connoisseur of both the lowest and the highest social strata in their bitter underside hidden for the fearful eye, who was not deceived in the choice of his main literary pseudonym after a short stay as Yehudiel Khlamida.

With Gorky we will begin our final story of The Paths of Russian Love. In it we will also need to resort to a more comparative view of the trajectories of love from those corners of the international love triangle we outlined at the beginning of our trilogy, so let us recall them briefly here.

In the West, the transformations of love relations in the twentieth century were no less radical. Generated by new-fangled philosophical theories and spontaneous social movements, up to the famous radical sexual revolution of the 60—70s and the «pink», hybrid war for gender equality, they migrated into the XXI century, where there are still occasional flashes of media battles with disparate representatives of conservative forces. Now the eyes of enthusiastic technocrats, amplified by the finances of those interested in prolonging human life and earthly pleasures, are turned to the tantalizing advances in human empowerment through genetic engineering, robotization, and artificial intelligence. The contours of the new technosubject are still blurred, and love lives on in the wreckage of twentieth-century meanings.

French intellectuals in the last century have done a tremendous job of exploring the modern subject, building on the legacy of Nietzsche and Heidegger. Jean-Paul Sartre and his wife Simone de Beauvoir concluded that the love relationship, although filled with the joy of individual freedom, is internally contradictory – illusory, conflictual, and largely associated with self-deception, leading the subject away from his true purpose in life (authentic existence). Rejecting the determinism of psychoanalysis, which dominated the understanding of human nature, they argued that the individual independently chooses himself or herself in various spheres of life, including «through erotic experience». At the same time, however, they noted the special intensity of erotic experiences, in which «people feel most acutely the duality of their nature; in erotic experience they feel themselves both flesh and spirit; both the Other and the subject.»

Michel Foucault saw the European history of sexuality as a human endeavor to discover the truth about the nature of romantic desire and exposed the precariousness of «absolute values» as the ideological foundations of moral norms imposed by power structures to maintain social hierarchy. He saw «sexual experience or abstinence» as one of a long history of practices performed by people «on their bodies and souls, thoughts, behavior, and way of life, in order to transform themselves to achieve a certain state of happiness, purity, wisdom, perfection, or immortality.»

It is worth noting, however, that these rather unpretentious and skeptical views on love by French thinkers clearly did not correspond to the exceptional character of provocative, sometimes bizarre and invariably dizzying personal love stories. Just as Nietzschean love romanticism in the works of Maxim Gorky did not fully reflect the ornate intricacy of his love preferences.

Across the ocean, Foucault’s ideas about the history of sexuality and the practices of human self-care were greeted enthusiastically in the late 1970s and early 1980s, but quickly dissolved into a global mass of imported novelties, their own insights into the nature of love and the techniques of romantic relationships emerging from the surface of psychoanalysis deeply embedded in all social pores of American society.

All three soils of love’s germination at the turn of the twentieth century have not escaped the suffocating embrace of postmodernism, the mighty equalizer of great and primitive ideas that has seized the banner of the champion of individual freedom. It has now become pointless, alone, with a partner, or with like-minded people, to seek or defend the truth found in love matters. All models of love are studied in detail, known and outlined in popular books on self-improvement. Everyone is free to choose the one he likes, and if it does not fit, then change, and more than once. There is no need to defend this or that choice of intimate life, even the most exotic one – tolerance in the West has already become ubiquitous, and sometimes it is even abused. It would seem that the end of the sexual history of mankind has come?

Alas! Even the naked eye can see that people in the majority continue to search for their special and truly genuine love. If it does not succeed in their personal destiny, they follow with intense curiosity the love stories of celebrities or heroes of television series. This «inherent human thirst» and inexhaustible spontaneous practice of love continues to be watched by keen minds, and here and there new conceptions of love emerge, seeking to encompass its entire multidimensional and frighteningly ramified flow. We dare to assume that one of the newest interpretations of love, proposed by British philosophy professor Simon May in 2019 and published under the title Love: A New Understanding of an Ancient Emotion, which we will present in the last chapter of our book, will soon be imported to the United States, where in twenty years it will become the mainstream1 of love relationships in the country – the trendsetter of fashions and mores of the modern free world.

Unless in Russia will not happen…

However, let’s take everything in order and get acquainted with Maxim Gorky’s first love and his Old Lady Izergil.

I

From the bottom of the people. Unnatural feelings. Legends of cruel love. Alien worlds. Feverish thoughts. Woman’s tender word. Sense of the real self. Romantic soul. Ultimate suffering. Innermost desire. Litmus test of love. Real woman. Study of love. Nightmares of doppelgangers

The French diplomat and literary critic Count Eugène-Melchior de Vogüé in his book Maxim Gorky, published in 1902, speaks of Gorky as a talent that surfaced «from the bottom of the people», the curiosity about whom is connected with the «primordial power of the people» manifested in his works. If this is true, then perhaps Gorky has managed to say something truly new, undistorted, and grounded about Russian love. But the meticulous critic sees no novelty in the vivid characters portrayed by Gorky – Makar Chudra, who «speaks of the cruel love of the Kuban beauties,» and the formerly beautiful Old Lady Izergil, a dozen love stories of which is like a continuation of ancient legends about the death-bearing love of the proud and cold-bloodedly accepted sacrificial love. Count de Vogüé finds in the «unnatural, conventional feelings» of Gorky’s heroes traces of suggestion of the «fathers of romanticism.»

So we will not find in Gorky apt sketches about Russian love? Not quite so. Let’s pay attention to what overlooked the sharp eye of the French critic. The sizzling love stories of Old Lady Izergil – all dramas and tragedies – are listened to by a Russian guy, young and strong, but «gloomy as a demon.» The local Moldavian girls are afraid of him, he is alien to their merry round dances, and the old woman stigmatizes all Russian men in his person as «born old men.»

Makar Chudra tells the ultimate drama of gypsy love to a young man traveling the world to learn about life. And this Russian young man seeking knowledge about life and love discovers that there are two worlds: in one, they think about life, study and teach others, but live like slaves, and in the other they do not ask questions about what they live for and why they love, but rejoice in life, spreading the wings of their free will like a bird over the steppe expanses. Then it becomes clear to us: what the young Peshkov discovers in his wanderings and then describes in highly artistic stories, was originally in his soul, that in the sweet, dizzying experiences of early love he had already encountered these two worlds – in their own way alien and frightening abysses.

What choice could there be for a «healthy young man, fond of dreaming of good things,» eager to get out of everything «slowly and foully simmering around him,» but entangled in the «feverish activity of thought»? His motive for suicide at the age of nineteen, Gorky twenty-five years later tried to explain in the story An incident in the life of Makar, where the hero felt in love with two cheerful, lively, intelligent girls who could, by saying «a tender word,» relieve him of «loneliness, longing.» He believes that «no one needs me and I do not need anyone, and, having prepared a revolver, glances at the portraits of the rulers of his innermost thoughts, incompatible with a dull life: the fighter for the happiness of people, the socialist Robert Owen, the famous beauty and mistress of the Parisian salon in revolutionary France Julia Recamier and sharp literary critic Belinsky with a «prickly, bird-like face2.»

In 1889, two years after the failed suicide, Gorky, still self-seeking, but having already begun to write, met «a slender girl with bluish eyes,» who would tell him the right affectionate woman’s word. Olga Kamenskaya was ten years older than Gorky, had already been married and lived in Paris. He fell in love with her, but she, also having a tender feeling for him, did not decide to immediately leave the «helpless» spouse. More than two years later, they accidentally happened to be in Tiflis, explained themselves and began a new life together. Being already an experienced fifty-year-old writer, in 1922 Gorky published a story about his short-lived first love. This masterful work combines filigree artistic expression and a deep understanding of the driving forces and laws of love.

Maxim Gorky (1868—1936)

Initially, Gorky discovers love in himself as a «romantic dream,» as

something unknown, and it conceals a high, secret meaning of communication with a woman, something great, joyful and even terrible lurks behind the first embrace – having experienced this joy, a man is completely reborn.

This romantic dream is connected not so much with the external attractiveness of the beloved, but with the thirst for transformation of the lover himself and the feeling of the presence of the necessary supports and energies in love. The young Gorky was sure that

this woman is able to help me not only to feel the real me, but she can do something magical, after which I immediately free myself from the captivity of dark impressions of existence, something forever thrown out of my soul, and it will burst into flames of great power, great joy.

She knew much more about love and told him about her time at the institute, how Tsar Alexander II came to them and «beautiful girls disappeared, going hunting with the Tsar,» about Paris, about «the romances that she herself had experienced.»

Once she expressed a comparison between the Russians and the French in love:

A Russian in love is always somewhat verbose and heavy, and often disgusted by eloquence. Only the French know how to love beautifully; for them love is almost a religion —

which prompted him to look back on his love manners.

When one day «in the bluish light of the moon» she learned of the pure romantic fold of his soul, she stated with tears and deep regret that she had made a mistake and now understood that «she is not what he needs, not that!» And this cannot be corrected, since she has long since ceased to be a girl.

Gorky’s romantic dream also included the desire to arouse in his beloved woman «a thirst for freedom, beauty.» He tried to express this idea in the story Old Lady Izergil and, when he saw that the «closest» to him woman «firmly asleep», interrupted reading and thought… Gorky realized that even his powerful, like a bell, love is unable to change, or rather, to return what she herself considered irretrievably lost: «the dream of heavenly bliss of love.»

It seems unlikely the restrained and ironic attitude of the young Gorky to his wife’s coquetry, her «striving to shake up men» and the gossip spread about her, depicted in the story of his first love, which is peculiar rather to the view of an already aged author, but it vividly highlights his main suffering – that she could tell another his deepest «feelings, thoughts and conjectures, which you tell only to the woman you love and will not tell anyone else». He also began to feel that the love that had been the support of his innermost life path – literary creativity – was now, in its non-ideal incarnation, knocking him down; this absolute love could not absorb or transform what was rejected, and they, «after a little silent sadness,» parted.

In this autobiographical story we can also find a third component of Gorky’s feelings of love – a «romantic dream» associated with the peculiarity of his nature, manifested in the unbearableness of human suffering, especially when it is associated with violence and insults, which «threw him out of life». For Gorky, this was an internal «litmus test», a tuning fork of kinship of souls. When he discovered deep-rooted spiritual callousness in his loved ones, something broke off in his own soul, and he became cold to them. He cites the case of how his first love exposed her inability to share compassion for a one-eyed old Jewish man who had been humiliatingly beaten by a policeman, imagining a picture of inhuman abuse painted with «anguish and anger» and concluding that her husband was too impressionable and had «bad nerves.» To this we can add that, according to the testimony of the daughter of Gorky’s second common-law wife, Maria Andreyeva, a sharp «divergence of political opinions» regarding the rejection of repression and bloody massacre of the Bolsheviks against their apparent and fictitious political enemies, was one of the reasons for the breakup of passionately begun, cemented by friendship and joint work sixteen-year relationship.

At the conclusion of the story Gorky, respectfully calling Olga Kamenskaya а glorious, «real woman», explains how this was expressed. A real woman of Gorky liked it when he, «barely touching the skin of her face with his fingers, smoothed out the slightly noticeable wrinkles under her lovely eyes»; «loved her body and, naked, standing in front of the mirror, admired»; was «restlessly cheerful by nature, witty, flexible, like a snake»; never once complained about the difficult conditions of life; «could sew beautifully» and dress up; was original in her interest in people, believing that «suddenly there is something stored there that is not visible to anyone, never shown, only I alone – and I am the first – will see it».

In the story On First Love Gorky also touches on the rather acute issue of the appropriateness of «talking about love», on which, as a rule, extremely opposite points of view are expressed. Gorky’s «Parisienne» was burdened by the verbosity of her Russian admirers, and «taught» him not to philosophize too much.

In another mirror situation, the roles are reversed. The hero of his last multi-volume novel The Life of Klim Samgin, having entered into a relationship with Lydia, his first, childhood love, cannot understand why she thinks so much about what is happening to them, and in response to her breathtaking questions he finds «not stupid words»:

This is not love for you, but an exploration of love.

Indeed, Lydia, for example, is tormented by a piercing question: why were the expectations of love so grandiose, and when it happened, everything turned out to be exciting and hot, but nothing more:

And this is all? For everyone – the same: for poets, cabbies, dogs?

When she, confused in her analysis of love, asks Samgin what she lacks, he responds in a stereotyped way, not knowing the right answer himself: «Simplicity». After the connection with Lydia, who had left for Paris, had quickly «flared up like shavings», he thought for a moment and clarified the diagnosis: «She is soulless. Smarts, but does not feel.» But the point in their love story is set by her, passing him letters not sent from Paris, in which she tried to explain her disappointment in love, or rather, in what is called love in the midst of the «vulgar meaninglessness of life».

There is a lot of talk about love in this novel by Gorky. Samgin’s mother instructs him that «all women are incurably ill with loneliness. From this – everything incomprehensible to you men, unexpected cheating and… everything!» One of Samgin’s female acquaintances informs him of the truth, heard from a philosopher, «amazingly slovenly and ugly», that man has three basic instincts: hunger, love and knowledge – and this philosopher, it turns out, was Samgin’s teacher and wooed his mother. The failed groom, drunk with grief, responds to Samgin’s attempt to console him by remarking on the chosen one’s shallow mind and her inability to «understand why one should love», and categorically states that «mind is against love». Gorky supplements Chekhov’s characteristic trait of Russians, which is expressed in love for conversations about love, in which only questions are raised, with contempt for such empty conversations, but at the same time endows his characters with intense inner thinking about love, connected with the dream of its high incarnations.

The thinking dreamer Klim Samgin is surprised to note how his second love, no longer «dressed up as romantic hopes» but manifesting itself as «a free and reasonable desire to possess a maiden,» causes confusion in his airy castles guarded by a fastidious mind. The unexpected sacrifice of Varvara, a perky «sharp-nosed maiden» in love with him, who turned out to be a virgin and secretly had an abortion so as not to burden Samgin, surprised him and revived his faith in the «festive» feeling. He even wanted to «say to Varvara some extraordinary and decisive word that would bring her even more and finally closer to him.» In his relationship with Varvara, he even wants to «feel both for himself and for the woman at the same time,» because then «love would be more perfect, richer.» However, three years later he thinks that «this woman is already read by him, she is uninteresting.»

A succession of subsequent loves adds a pittance to Klim Samgin’s store of knowledge about love, women, and himself. Mistress Nikonova, who turns out to be a gendarme agent, «stronger or smarter than him in some ways,» allows him to speak his most intimate thoughts – «the dirt of his soul» – so that he even feels the desire to have a child with her. Alina, who lives by her beauty and whose relationships with admirers for soul and body Samgin observes, reinforces the inference made «from his experience, from the novels he has read» (he has read Schopenhauer, Nietzsche, and Weininger) that women «everywhere but in the bedroom are a nuisance, and in the bedroom they are pleasant for a short time.» When he compares the «perky» Dunyasha, Alina’s friend, with Nikonova, he finds that «the latter was more comfortable, and the former knows better than anyone else the art of enjoying the body», and recognizes himself as «somewhat spoiled.» And Doctor Makarov, philosophizing about his relationship with Alina, is convinced that «a woman half-consciously seeks to reveal a man to the last line, to understand the source of his power over her.»

Like a meticulous chronicler of Russian sexuality, Gorky tangentially confronts Samgin with Marina Premirova, «lush girl» with a thick braid of golden color, who perceived men «scary and ambiguously, then – the flesh, then – the spirit,» «thought unusually and could not express her true thoughts in words.» Samgin’s lover Nekhaeva, who is under Marina’s care and is greedy for affection, sees in her something typically Russian:

She will love a lot; then, when tired, will love dogs, cats, with the same love as she loves me. So well-fed, so Russian.

But the «monumental» Marina, embodied in the «intelligent and imperious woman,» finds another, secretive way of love – she becomes the helmswoman of a religious anti-Christian sect, preaching «faith in the spirit of life» and united by Khlyst’s festivities, which she invites Samgin to watch through a peephole, although she realizes that this is alien to him.

Samgin, an exemplary Russian intellectual who «respects inner freedom,» realizes the powerlessness of his individual qualities in the face of «an endless series of silly, vulgar, but in general still dramatic episodes,» burdening the man with «unnecessary weight,» so that he, «cluttered, suppressed by them, ceases to feel himself, his being, perceives life as pain.» He finds refuge from the nightmare of life by «distributing his experiences among his doubles» – there are many of them, but they are all equally alien to him.

Perhaps, if Gorky had continued the biography, cut short by the sudden death of the appointed «official» writer from a cold at the age of sixty-eight, of a typical Russian intellectual, drawn into the maelstrom of wars and revolutions, he would have awarded him a meeting with an extraordinary woman who knows how to love men, such as Maria Zakrevskaya, who became for the famous writer the last desired, but still elusive love. She would have been able to delicately but firmly support his worship of reason, for which «there is nothing sacred, for he himself is the holy of holies and God himself,» and yet be «viable,» «incredibly charming,» «mistress of her own destiny,» so that close relations with other great people and other, even dark, forces would have been forgivable to her3.

According to some interpreters of Mikhail Bulgakov’s work, another famous writer, a young contemporary of Gorky, the novel The Master and Margarita, which provokes deserved delight and controversy, presents Gorky in the image of the Master. Then we can follow the faint threads that bind the torn age of Russian love and get acquainted with the image of an ideal woman who can love and help a man desperately and deeply absorbed in thinking about the fate of mankind.

II

Justified risk. Fast love. Broads in the past. Woman’s freedom. Disturbing yellow flowers. Struggle for love. Substitution of one’s nature. Heaviest vice. Liberation by love. Uncommon mercy