Полная версия

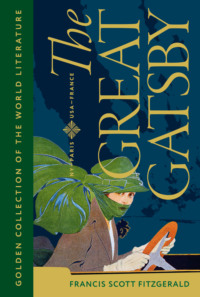

Великий Гэтсби / The Great Gatsby

“Doesn't she like Wilson either?”

The answer to this was unexpected. It came from Myrtle who had heard my question and it was violent and obscene, “Of course, not.”

“You see?” cried Catherine triumphantly. She lowered her voice again. “It's really his wife that's keeping them apart. She's a Catholic and they don't believe in divorce.”

Daisy was not a Catholic and I was a little shocked at this lie.

“When they get married,” continued Catherine, “they're going West to live for a while there.”

“Why not to Europe?”

“Oh, do you like Europe?” she exclaimed surprisingly. “I just got back from Monte Carlo.”

“Really?”

“Just last year. I went over there with a girl friend.”

“Stay long?”

“No, we just went to Monte Carlo and back. We had more than twelve hundred dollars when we started but we lost everything. God, how I hated that town!”

“I almost made a mistake, too,” Mrs. McKee declared vigorously. “I almost married a man who was below me. Everybody was saying to me: 'Lucille, that man's below you!' But luckily I met Chester!”

“Yes, but listen,” said Myrtle Wilson, nodding her head up and down, “at least you didn't marry him.”

“I know I didn't.”

“And I married him,” said Myrtle, ambiguously. “And that's the difference between your case and mine.”

“Why did you, Myrtle?” demanded Catherine. “Nobody forced you to.”

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «Литрес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на Литрес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Примечания

1

New Haven – имеется в виду Йельский университет (который находится в городе Нью-Хейвен).

2

police dogs – овчарки