Полная версия

The Romance of the Forest

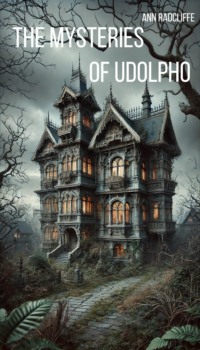

On his return to the abbey, La Motte ascended the stairs that led to the tower. About half way up, a door appeared in the wall; it yielded, without resistance, to his hand; but a sudden noise within, accompanied by a cloud of dust, made him step back and close the door. After waiting a few minutes, he again opened it, and perceived a large room of the more modern building. The remains of tapestry hung in tatters upon the walls, which were become the residence of birds of prey, whose sudden flight on the opening of the door had brought down a quantity of dust, and occasioned the noise. The windows were shattered, and almost without glass; but he was surprised to observe some remains of furniture; chairs, whose fashion and condition bore the date of their antiquity; a broken table, and an iron grate almost consumed by rust.

On the opposite side of the room was a door which led to another apartment, proportioned like the first, but hung with arras somewhat less tattered. In one corner stood a small bedstead, and a few shattered chairs were placed round the walls. La Motte gazed with a mixture of wonder and curiosity. 'Tis strange, said he, that these rooms, and these alone, should bear the marks of inhabitation; perhaps, some wretched wanderer like myself, may have here sought refuge from a persecuting world; and here, perhaps, laid down the load of existence; perhaps, too, I have followed his footsteps, but to mingle my dust with his! He turned suddenly, and was about to quit the room, when he perceived a small door near the bed; it opened into a closet, which was lighted by one small window, and was in the same condition as the apartments he had passed, except that it was destitute even of the remains of furniture. As he walked over the floor, he thought he felt one part of it shake beneath his steps, and, examining, found a trap-door. Curiosity prompted him to explore further, and with some difficulty he opened it. It disclosed a staircase which terminated in darkness. La Motte descended a few steps, but was unwilling to trust the abyss; and, after wondering for what purpose it was so secretly constructed, he closed the trap, and quitted this suit of apartments.

The stairs in the tower above were so much decayed, that he did not attempt to ascend them: he returned to the hall, and by the spiral staircase which he had observed the evening before, reached the gallery, and found another suit of apartments entirely furnished, very much like those below.

He renewed with Madame La Motte his former conversation respecting the abbey, and she exerted all her endeavours to dissuade him from his purpose, acknowledging the solitary security of the spot, but pleading that other places might be found equally well adapted for concealment and more for comfort. This La Motte doubted: besides, the forest abounded with game, which would, at once, afford him amusement and food, a circumstance, considering his small stock of money, by no means to be overlooked; and he had suffered his mind to dwell so much upon the scheme, that it was become a favourite one. Adeline listened in anxiety to the discourse, and waited the issue of Peter's report.

The morning passed but Peter did not return. Our solitary party took their dinner of the provision they had fortunately brought with them, and afterwards walked forth into the woods. Adeline, who never suffered any good to pass unnoticed because it came attended with evil, forgot for a while the desolation of the abbey in the beauty of the adjacent scenery. The pleasantness of the shades soothed her heart, and the varied features of the landscape amused her fancy; she almost thought she could be contented to live here. Already she began to feel an interest in the concerns of her companions, and for Madame La Motte she felt more; it was the warm emotion of gratitude and affection.

The afternoon wore away, and they returned to the abbey. Peter was still absent, and his absence now began to excite surprise and apprehension. The approach of darkness also threw a gloom upon the hopes of the wanderers: another night must be passed under the same forlorn circumstances as the preceding one! and, what was still worse, with a very scanty stock of provisions. The fortitude of Madame La Motte now entirely forsook her, and she wept bitterly. Adeline's heart was as mournful as Madame's, but she rallied her drooping spirits, and gave the first instance of her kindness by endeavouring to revive those of her friend.

La Motte was restless and uneasy, and, leaving the abbey, he walked alone the way which Peter had taken. He had not gone far, when he perceived him between the trees, leading his horse. – What news, Peter? hallooed La Motte. Peter came on, panting for breath, and said not a word, till La Motte repeated the question in a tone of somewhat more authority. Ah, bless you, master! said he, when he had taken breath to answer, I am glad to see you; I thought I should never have got back again: I've met with a world of misfortunes.

Well, you may relate them hereafter; let me hear whether you have discovered —

Discovered? interrupted Peter, yes, I am discovered with a vengeance! if your honour will look at my arms, you'll see how I am discovered.

Discoloured! I suppose you mean, said La Motte. But how came you in this condition!

Why I tell you how it was, Sir; your honour knows I learnt a smack of boxing of that Englishman that used to come with his master to our house.

Well, well – tell me where you have been.

I scarcely know myself, master; I've been where I got a sound drubbing, but then it was in your business, and so I don't mind. But if ever I meet with that rascal again! —

You seem to like your first drubbing so well, that you want another, and unless you speak more to the purpose, you shall soon have one.

Peter was now frightened into method, and endeavoured to proceed: When I left the old abbey, said he, I followed the way you directed, and turning to the right of that grove of trees yonder, I looked this way and that to see if I could see a house or a cottage, or even a man, but not a soul of them was to be seen, and so I jogged on near the value of a league, I warrant, and then I came to a track; Oh! oh! says I, we have you now; this will do – paths can't be made without feet. However, I was out in my reckoning, for the devil a bit of a soul could I see, and after following the track this way and that way, for the third of a league, I lost it, and had to find out another.

Is it impossible for you to speak to the point? said La Motte; omit these foolish particulars, and tell whether you have succeeded.

Well, then, master, to be short, for that's the nearest way after all, I wandered a long while at random, I did not know where, all through a forest like this, and I took special care to note how the trees stood, that I might find my way back. At last I came to another path, and was sure I should find something now, though I had found nothing before, for I could not be mistaken twice; so, peeping between the trees, I spied a cottage, and I gave my horse a lash that sounded through the forest, and I was at the door in a minute. They told me there was a town about half a league off, and bade me follow the track and it would bring me there, – so it did; and my horse, I believe, smelt the corn in the manger by the rate he went at. I inquired for a wheel-wright, and was told there was but one in the place, and he could not be found. I waited and waited, for I knew it was in vain to think of returning without doing my business. The man at last came home from the country, and I told him how long I had waited; for, says I, I knew it was in vain to return without my business.

Do be less tedious, said La Motte, if it is in thy nature.

It is in my nature, answered Peter, and if it was more in my nature your honour should have it all. Would you think it, Sir, the fellow had the impudence to ask a louis-d'or for mending the coach-wheel! I believe in my conscience he saw I was in a hurry and could not do without him. A louis-d'or! says I, my master shall give no such price, he sha'n't be imposed upon by no such rascal as you. Whereupon, the fellow looked glum, and gave me a douse o'the chops: with this, I up with my fist and gave him another, and should have beat him presently, if another man had not come in, and then I was obliged to give up.

And so you are returned as wise as you went?

Why, master, I hope I have too much spirit to submit to a rascal, or let you submit, to one either: besides, I have bought some nails to try if I can't mend the wheel myself – I had always a hand at carpentry.

Well, I commend your zeal in my cause, but on this occasion it was rather ill-timed. And what have you got in that basket?

Why, master, I bethought me that we could not get away from this place till the carriage was ready to draw us, and in the mean time, says I, nobody can live without victuals, so I'll e'en lay out the little money I have and take a basket with me.

That's the only wise thing you have done yet, and this, indeed, redeems your blunders.

Why now, master, it does my heart good to hear you speak; I knew I was doing for the best all the while: but I've had a hard job to find my way back; and here's another piece of ill luck, for the horse has got a thorn in his foot.

La Motte made inquiries concerning the town, and found it was capable of supplying him with provision, and what little furniture was necessary to render the abbey habitable. This intelligence almost settled his plans, and he ordered Peter to return on the following morning and make inquiries concerning the abbey. If the answers were favourable to his wishes, he commissioned him to buy a cart and load it with some furniture, and some materials necessary for repairing the modern apartments. Peter stared: What, does your honour mean to live here?

Why, suppose I do?

Why, then your honour has made a wise determination, according to my hint; for your honour knows I said —

Well, Peter, it is not necessary to repeat what you said; perhaps I had determined on the subject before.

Egad, master, you're in the right, and I'm glad of it, for I believe we shall not quickly be disturbed here, except by the rooks and owls. Yes, yes – I warrant I'll make it a place fit for a king; and as for the town, one may get any thing, I'm sure of that; though they think no more about this place than they do about India or England, or any of those places.

They now reached the abbey; where Peter was received with great joy: but the hopes of his mistress and Adeline were repressed, when they learned that he returned without having executed his commission, and heard his account of the town. La Motte's orders to Peter were heard with almost equal concern by Madame and Adeline; but the latter concealed her uneasiness, and used all her efforts to overcome that of her friend. The sweetness of her behaviour, and the air of satisfaction she assumed, sensibly affected Madame, and discovered to her a source of comfort which she had hitherto overlooked. The affectionate attentions of her young friend promised to console her for the want of other society, and her conversation to enliven the hours which might otherwise be passed in painful regret.

The observations and general behaviour of Adeline already bespoke a good understanding and an amiable heart; but she had yet more – she had genius. She was now in her nineteenth year; her figure of the middling size, and turned to the most exquisite proportion; her hair was dark auburn, her eyes blue, and whether they sparkled with intelligence, or melted with tenderness, they were equally attractive: her form had the airy lightness of a nymph, and when she smiled, her countenance might have been drawn for the younger sister of Hebe: the captivations of her beauty were heightened by the grace and simplicity of her manners, and confirmed by the intrinsic value of a heart.

That might be shrined in chrystal,And have all its movements scann'd.Annette now kindled the fire for the night: Peter's basket was opened, and supper prepared. Madame La Motte was still pensive and silent. – There is scarcely any condition so bad, said Adeline, but we may one time or the other wish we had not quitted it. Honest Peter, when he was bewildered in the forest, or had two enemies to encounter instead of one, confesses he wished himself at the abbey. And I am certain, there is no situation so destitute, but comfort may be extracted from it. The blaze of this fire shines yet more cheerfully from the contrasted dreariness of the place; and this plentiful repast is made yet more delicious from the temporary want we have suffered. Let us enjoy the good and forget the evil.

You speak, my dear, replied Madame La Motte, like one whose spirits have not been often depressed by misfortune (Adeline sighed), and whose hopes are therefore vigorous. Long suffering, said La Motte, has subdued in our minds that elastic energy which repels the pressure of evil and dances to the bound of joy. But I speak in raphsody, though only from the remembrance of such a time. I once, like you, Adeline, could extract comfort from most situations.

And may now, my dear Sir, said Adeline. Still believe it possible, and you will find it is so.

The illusion is gone – I can no longer deceive myself.

Pardon me, Sir, if I say, it is now only you deceive yourself, by suffering the cloud of sorrow to tinge every object you look upon.

It may be so, said La Motte, but let us leave the subject.

After supper, the doors were secured, as before, for the night, and the wanderers resigned themselves to repose.

On the following morning, Peter again set out for the little town of Auboine, and the hours of his absence were again spent by Madame La Motte and Adeline in much anxiety and some hope, for the intelligence he might bring concerning the abbey might yet release them from the plans of La Motte. Towards the close of the day he was descried coming slowly on; and the cart, which accompanied him, too certainly confirmed their fears. He brought materials for repairing the place, and some furniture.

Of the abbey he gave an account, of which the following is the substance: – It belonged, together with a large part of the adjacent forest, to a nobleman, who now resided with his family on a remote estate. He inherited it, in right of his wife, from his father-in-law, who had caused the more modern apartments to be erected, and had resided in them some part of every year, for the purpose of shooting and hunting. It was reported, that some person was, soon after it came to the present possessor, brought secretly to the abbey and confined in these apartments; who, or what he was, had never been conjectured, and what became of him nobody knew. The report died gradually away, and many persons entirely disbelieved the whole of it. But however this affair might be, certain it was, the present owner had visited the abbey only two summers since his succeeding to it; and the furniture after some time, was removed.

This circumstance had at first excited surprise, and various reports rose in consequence, but it was difficult to know what ought to be believed. Among the rest, it was said that strange appearances had been observed at the abbey, and uncommon noises heard; and though this report had been ridiculed by sensible persons as the idle superstition of ignorance, it had fastened so strongly upon the minds of the common people, that for the last seventeen years none of the peasantry had ventured to approach the spot. The abbey was now, therefore, abandoned to decay.

La Motte ruminated upon this account. At first it called up unpleasant ideas, but they were soon dismissed, and considerations more interesting to his welfare took place: he congratulated himself that he had now found a spot where he was not likely to be either discovered or disturbed; yet it could not escape him that there was a strange coincidence between one part of Peter's narrative, and the condition of the chambers that opened from the tower above stairs. The remains of furniture, of which the other apartments were void – the solitary bed – the number and connexion of the rooms, were circumstances that united to confirm his opinion. This, however, he concealed in his own breast, for he already perceived that Peter's account had not assisted in reconciling his family to the necessity of dwelling at the abbey.

But they had only to submit in silence, and whatever disagreeable apprehension might intrude upon them, they now appeared willing to suppress the expression of it. Peter, indeed, was exempt from any evil of this kind; he knew no fear, and his mind was now wholly occupied with his approaching business. Madame La Motte, with a placid kind of despair, endeavoured to reconcile herself to that which no effort of understanding could teach her to avoid, and which an indulgence in lamentation could only make more intolerable. Indeed, though a sense of the immediate inconveniences to be endured at the abbey had made her oppose the scheme of living there, she did not really know how their situation could be improved by removal: yet her thoughts often wandered towards Paris, and reflected the retrospect of past times, with the images of weeping friends left, perhaps, for ever. The affectionate endearments of her only son, whom, from the danger of his situation, and the obscurity of hers, she might reasonably fear never to see again, arose upon her memory and overcame her fortitude. Why – why was I reserved for this hour? would she say, and what will be my years to come?

Adeline had no retrospect of past delight to give emphasis to present calamity – no weeping friends – no dear regretted objects to point the edge of sorrow, and throw a sickly hue upon her future prospects: she knew not yet the pangs of disappointed hope, or the acuter sting of self-accusation; she had no misery but what patience could assuage, or fortitude overcome.

At the dawn of the following day Peter arose to his labour: he proceeded with alacrity, and in a few days two of the lower apartments were so much altered for the better that La Motte began to exult, and his family to perceive that their situation would not be so miserable as they had imagined. The furniture Peter had already brought was disposed in these rooms, one of which was the vaulted apartment. Madame La Motte furnished this as a sitting-room, preferring it for its large Gothic window, that descended almost to the floor, admitting a prospect of the lawn, and the picturesque scenery of the surrounding woods.

Peter having returned to Auboine for a further supply, all the lower apartments were in a few weeks not only habitable, but comfortable. These, however, being insufficient for the accommodation of the family, a room above stairs was prepared for Adeline: it was the chamber that opened immediately from the tower, and she preferred it to those beyond, because it was less distant from the family, and the windows fronting an avenue of the forest afforded a more extensive prospect. The tapestry, that was decayed, and hung loosely from the walls, was now nailed up, and made to look less desolate; and though the room had still a solemn aspect, from its spaciousness and the narrowness of the windows, it was not uncomfortable.

The first night that Adeline retired hither, she slept little: the solitary air of the place affected her spirits; the more so, perhaps, because she had, with friendly consideration, endeavoured to support them in the presence of Madame La Motte. She remembered the narrative of Peter, several circumstances of which had impressed her imagination in spite of her reason, and she found it difficult wholly to subdue apprehension. At one time, terror so strongly seized her mind, that she had even opened the door with an intention of calling Madame La Motte; but, listening for a moment on the stairs of the tower, every thing seemed still: at length, she heard the voice of La Motte speaking cheerfully, and the absurdity of her fears struck her forcibly; she blushed that she had for a moment submitted to them, and returned to her chamber wondering at herself.

Chapter III

Are not these woodsMore free from peril than the envious court?Here feel we but the penalty of Adam,The season's difference, as the icy fangAnd churlish chiding of the winter's wind.SHAKSPEARE.La Motte arranged his little plan of living. His mornings were usually spent in shooting or fishing, and the dinner, thus provided by his industry, he relished with a keener appetite than had ever attended him at the luxurious tables of Paris. The afternoons he passed with his family: sometimes he would select a book from the few he had brought with him, and endeavoured to fix his attention to the words his lips repeated: – but his mind suffered little abstraction from its own cares, and the sentiment he pronounced left no trace behind it. Sometimes he conversed, but oftener sat in gloomy silence, musing upon the past, or anticipating the future.

At these moments, Adeline, with a sweetness almost irresistible, endeavoured to enliven his spirits, and to withdraw him from himself. Seldom she succeeded; but when she did, the grateful looks of Madame La Motte, and the benevolent feelings of her own bosom, realized the cheerfulness she had at first only assumed. Adeline's mind had the happy art, or, perhaps, it were more just to say, the happy nature, of accommodating itself to her situation. Her present condition, though forlorn, was not devoid of comfort, and this comfort was confirmed by her virtues. So much she won upon the affections of her protectors, that Madame La Motte loved her as her child, and La Motte himself, though a man little susceptible of tenderness, could not be insensible to her solicitudes. Whenever he relaxed from the sullenness of misery, it was at the influence of Adeline.

Peter regularly brought a weekly supply of provisions from Auboine, and, on those occasions, always quitted the town by a route contrary to that leading to the abbey. Several weeks having passed without molestation, La Motte dismissed all apprehension of pursuit, and at length became tolerably reconciled to the complexion of his circumstances.

As habit and effort strengthened the fortitude of Madame La Motte, the features of misfortune appeared to soften. The forest, which at first seemed to her a frightful solitude, had lost its terrific aspect; and that edifice, whose half demolished walls and gloomy desolation had struck her mind with the force of melancholy and dismay, was now beheld as a domestic asylum, and a safe refuge from the storms of power.

She was a sensible and highly accomplished woman, and it became her chief delight to form the rising graces of Adeline, who had, as has been already shown, a sweetness of disposition, which made her quick to repay instruction with improvement, and indulgence with love. Never was Adeline so pleased as when she anticipated her wishes, and never so diligent as when she was employed in her business. The little affairs of the household she overlooked and managed with such admirable exactness, that Madame La Motte had neither anxiety nor care concerning them. And Adeline formed for herself in this barren situation, many amusements that occasionally banished the remembrance of her misfortunes. La Motte's books were her chief consolation. With one of these she would frequently ramble into the forest, where the river, winding through a glade, diffused coolness, and with its murmuring accents invited repose: there she would seat herself, and, resigned to the illusions of the page, pass many hours in oblivion of sorrow.

Here too, when her mind was tranquillized by the surrounding scenery, she wooed the gentle muse, and indulged in ideal happiness. The delight of these moments she commemorated in the following address:

TO THE VISIONS OF FANCYDear, wild illusions of creative mind!Whose varying hues arise to Fancy's art,And by her magic force are swift combinedIn forms that please, and scenes that touch the heart:Oh! whether at her voice ye soft assumeThe pensive grace of sorrow drooping low;Or rise sublime on terror's lofty plume,And shake the soul with wildly thrilling woe;Or, sweetly bright, your gayer tints ye spread,Bid scenes of pleasures steal upon my view,Love wave his purple pinions o'er my head,And wake the tender thought to passion true.O! still – ye shadowy forms! attend my lonely hours,Still chase my real cares with your illusive powers!Madame La Motte had frequently expressed curiosity concerning the events of Adeline's life, and by what circumstances she had been thrown into a situation so perilous and mysterious as that in which La Motte had found her. Adeline had given a brief account of the manner in which she had been brought thither, but had always with tears entreated to be spared for that time from a particular relation of her history. Her spirits were not then equal to retrospection; but now that they were soothed by quiet, and strengthened by confidence, she one day gave Madame La Motte the following narration.