Полная версия

Allamjonov's fault

That's why it was so hard to get into manufacturing; they only let their own into that business. Generally speaking, everyone was interested only in making a fast buck: something you invest in today and start seeing a return tomorrow, a business that you could painlessly bin off anytime and switch for something else. There weren't many people who planned to build a business empire to last a century. That's why, in our country, there are so few stories of people becoming rich from owning long-standing manufacturing or production businesses.

1998-1999

At the gymnasium, my classmates included the child-ren of public prosecutors and members of parliament, and I felt a constant need to prove to everybody around me that I was no less worthy than them. It wasn't bribes and phone calls that got me in, I was there for my brains. My parents may have been simple folk, but they never let anyone look down their nose at them. One notable example of me following in their footsteps came after our headmaster commented in front of everyone:

«Focus on your studies, Allamjonov, you'll never get a contract. I mean, your parents aren't exactly going to give you one».

In response I slashed the tires of his new Moskvich car. That's how I coped with being humiliated in front of the entire class.

My classmates began treating me nicely, especially after I formed my own group, Fun Boys, and we started to put on shows. I was the group's director. We used to make fun of the teachers. Not all of them, of course, just those we thought were bad at their job, excessively strict, or who took bribes.

One I remember is the «D and a half» teacher. No matter how well you did your homework, she'd always give it a «D and a half» That grade didn't even exist. She invented it herself as a way of putting us down. In our performance, «she» came out on stage and said:

After the Fun Boys show with classmates.

«I'm a physics teacher, my name is Muhtazar, and even after forty years, I haven't found a man who'll marry me».

Sure, it was harsh. It was after that that they called me in to see the headmaster. I listened to everything he had to say. But I didn't stop doing the shows.

At first, tickets were free. Then I thought, why? We were all putting so much effort into the lineup, the sketches, the music, and we were successful, so why should everybody get to enjoy it for nothing?

I went to my mum for the start-up capital we needed to organise the shows. I had to print tickets and flyers. Mum offered to ask dad for me, but I admitted I was afraid what he'd say. I was especially scared of telling dad what I needed the money for. My mum had always believed in me, and so she gave me 10,000 soms out of her own savings.

I got my friends to agree to sell tickets. None of them went to their parents for financial assistance; that was the organiser's problem or, in other words, mine. And my parents helped me.

I managed to secure us sponsors. The owner of the Turkish biscuit brand Aylin transferred 25,000 soms to the school's account. Of that, the headmaster gave me one and a half grand for amplifiers, I never saw any of the rest. He obviously swindled us.

Another one of our sponsors was Radio-Page2, which advertised our shows for free. Nestle gave out little plastic cups of their coffee and also put up some of their branded umbrellas. I had to ride all over the city making pitch after pitch to find and land those three sponsors. Nobody else apart from them agreed to help us at all.

I called Ravshan Sobirov's, Gulya Talipova's, and countless other artists' managers, asking if they'd consider appearing for free at our show. They agreed.

We didn't sell over a thousand tickets, of course, but we did sell a whole two hundred. The rest of the places we filled with courtesy tickets. To avoid looking bad in front of the sponsors, I got the director of the children's home to bring along his pupils.

Everybody had arrived. But…none of the artists had turned up. I called everyone, nobody was picking up. The audience were all clapping, an hour went by and still not one artist. After much scrambling, we managed to find one.

Fledgeling singer Davron Ergashev came and kicked off proceedings. Then we found a professional MC, who luckily agreed to host our event. Next, we found some guy who looked like the singer Otabek Madrahimov; we turned out the lights, hit the special effects, and out he came miming over a backing track.

We ran a few quizzes; the guests drank Nestle coffee. My career as a producer was safe.

Granted, someone did steal one of the Nestle umbrellas. They called my mum about it, and she went to fetch her own umbrella to give as a replacement. But they told her that they had paid for it in dollars, a currency my mother had never even seen with her own two eyes.

I managed to convince the CEO of Nestle to forget about the theft. I don't know why he agreed to drop it, probably because of how equally sad and honest I looked. As you might expect, I split the money from the ticket sales with my friend and partner, Sardor. We bought ourselves some cool sunglasses and trainers. It felt as though we were like real big-time events managers. I gave mum back a grand of the ten she'd given me and, with that, all the profit was gone.

But I didn't mind. For eight hundred people to come to the show, I think there was definitely an element of luck involved. And even some help from on high. I simply don't know what would have happened if we hadn't found the artists, most likely I would have had to get up and sing myself.

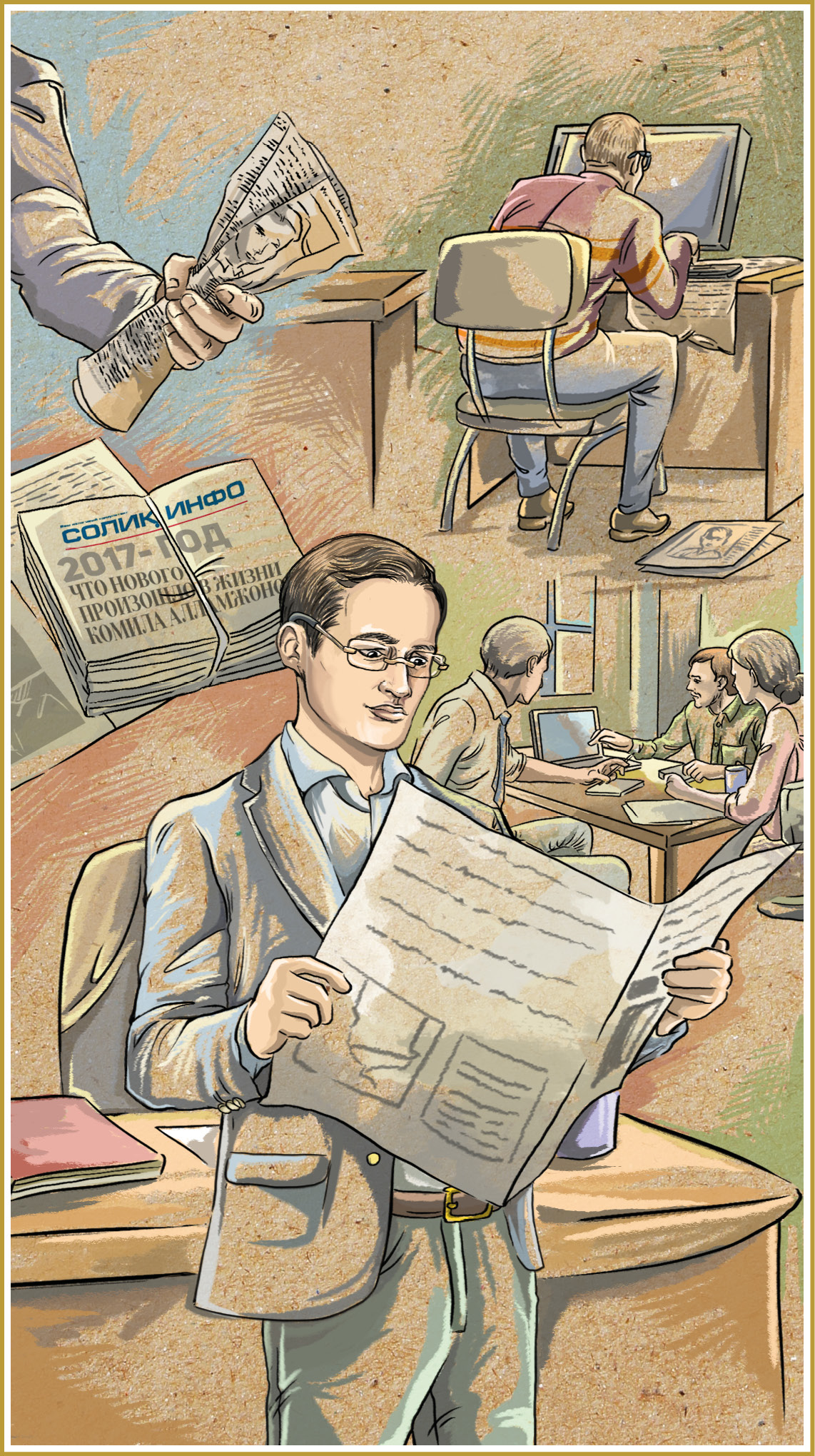

During my younger years, any foray into business was always an adventure. Nowadays, budding entrepreneurs learn how to put together clear and exhaustive business plans, count their money and calculate opportunities, analyse the market and evaluate their competition. Back then, though, we just latched ourselves onto an idea and ran with it, without any sort of plan. Our boat didn't need a rudder or even an oar, we just used to go whichever way the wind took us. And then, only once we'd set off on our journey did we realise what we needed to do to make money. That experience was the inspiration for my project Soliq-Info.

1 Musaffo osmon – «Serenety sky» the ideology widely used in Uzbekistan to exaggerate the public value of peace in the country

2 Company Radio PAGE Semurg – a paging company.

IV

Soliq-Info

During Karimov's reign, the only truly independent outlet, the editor of which everybody knew by face and name, was Uzmetronom. We would use a proxy server to visit it every day and read insider news, which editor Sergey Ezhkov used to present as «letters to the editor». But I have since realised that this resource was nothing more than an instrument for settling scores and had nothing to do with true freedom of speech.

At that time, if you wanted to go to President Karimov with a report, you needed grounds, so they would take a printout from Uzmetronom and say: «Look, this is what the press is writing…» The «press», meanwhile, was quite happy to pump out anything you asked them to. My name dominated the pages of the publication, Sergey Aleksandrovich took every step I made and put his own deft, artistic spin on it. His writing style was always top-class, but facts were rather lacking. There was just enough truth to give it an air of credibility.

It was he who «designated» me as «Parpiyev's nephew», and all of my successes, which were in actual fact failures, he attributed to my family connections.

An article in which he criticised the newspaper Soliq-Info for its compulsory subscription model featured the caption: «We already have a paper called Tax and Customs News, why does our country need another?». However, he neglected to mention that NTV was also a private publication that lived off compulsory subscriptions, just like all state-run publications, and even self-sustaining ones like Pravda Vostoka, Narodnoe Slovo, Na Postu, as well as a whole other host of newspapers and magazines. Virtually 99% of all the country's publications were compulsory subscriptions, but it was me who got all the «credit», even though I wasn't breaking any laws. The owners of all the other publications were kind enough to keep quiet. But that was to be expected. In those days, the harsh censorship regime wouldn't let you write the truth and, if a newspaper doesn't have anything inflammatory in it, no one will buy it. The government ensured subscriptions in exchange for loyalty.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «Литрес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на Литрес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.