Полная версия

Allamjonov's fault

Many people simply cannot understand that trust is earned with hard work and loyalty – by being fair and honest with people. They can't even get their head around it as a concept. For them, the only justification for someone trusting somebody else is that blood is thicker than water.

I didn't stay much longer at the Emergencies Ministry after Parpiyev left. But I do believe that the qualitative improvement in that department's information service was down to me personally.

Back then, nobody knew anything about the Emergencies Ministry; people had no idea that rescue personnel even existed because they were never shown in the media.

Meanwhile, the head of the department, Colonel Irgash Ikramov, was a stickler for cleanliness. Whenever he came to the building, the yard had to have been watered and his office had to smell like rue. For that reason, every single day, the yard would be scrubbed clean, and the rescue equipment polished until it sparkled, despite the fact that it was new and completely unused.

Initially, in a bid to drum up interest, we did some staged shoots inspired by past events, as-it-happened reconstructions. In actuality, we splotched ketchup on drivers to look like blood, like in films, and recreated floods and fires as they do for training exercises. We broadcast heroic content to show people how the Emergencies Ministry operates. Later, we started going to incidents with our camera and putting together pieces from live footage.

When the programme started to gain serious traction and real calls to the Rescue Service started to come in on the emergency number 050, the rescuers couldn't keep up. They made all sorts of rescues, from cats stuck down wells, to people trapped in lifts.

I remember one time, at the Zhemchug11, a man had decided to end it all by jumping from his ninth-floor apartment balcony. All the different services arrived together, and the rescuers were barely able to talk him out of jumping. They talked with him for four hours in affectionate, soothing tones. They persuaded him that we are only given one life, that everything was going to be okay. It was just like in a Hollywood movie. But when the man finally came down, they gave him a boot up the backside, swore at him and packed him off to a mental hospital as a suicide risk. To be fair, he'd just stolen four hours of their lives!

The rescue teams were often called out to accidents, where they would have to pull out people trapped in their cars. We started to show such incidents, making sure to highlight any incompetence by employees of the State Road Traffic Safety Department. Announced as the new Emergencies Minister was Bahtier Subanov, who up until then had been the Deputy Minister of Internal Affairs and who, in addition to the Emergencies Ministry, was also in charge of the State Motor Vehicle Inspectorate. It all looked like an act of revenge between former colleagues.

Subanov handed control of the press service to his own man, who then banned us from showing deaths or criticising the Ministry of Internal Affairs in our programme.

I fell in line and continued airing the kind of material I felt was needed. Oh, how it used to get on the nerves of Minister of Internal Affairs Zakir Almatov! You should have seen how they used to talk to me. The Ministry of Internal Affairs even got an addressing down from the Presidential Administration because of my stories. The Tashkent Internal Affairs Directorate went as far as to set up an «Allamjonov gagging unit». I was told that the Tashkent IAD was planning to plant cannabis on me and lock me up. That was a typical tactic they used on uncooperative individuals.

I arrived one morning at work to find police everywhere; they were looking for Allamjonov. Once again, I found myself at the centre of a scandal. It was Colonel Ikramov who saved me that time, interceding for me, saying that it wasn't right to destroy my life. For a month after that, I lived in fear. I wouldn't leave the house. Every day the traffic police would stop my driver on the street and give him grief for some nonexistent reason.

My entire first salary at the Emergencies Ministry went on drinks with my old colleagues. They referred to it as «popping the cork». So, after waiting all that time to be able to take it home to show my mum, I went and poured it down my drinking companions' necks instead. They reserved a table at a cafe just beside Shark12. Nothing of my first salary left that table with me. Only a few kopeks, which I took home.

My second salary, too, went the way of the first. But what could I say to those two dashing soldiers? Nothing.

The third time I had to use all my cunning and ask the cashier to give me my wages after everyone else. I took them and quickly ran home, so that my enthusiastic bosses and friends couldn't find me this time.

2005-2006 yy.

When he was President of the State Tax Committee, Parpiyev's first deputy was a man named Erkin Fayzievich Gadoev. Now, at the time, Islam Abduganievich Karimov pursued a divide-and-conquer policy. Ministers' deputies were always secretly opposed to them. It's possible that this gave Karimov more information about what was really going on, but it killed teamwork dead and only encouraged back-room dealings and intrigue. In the hierarchical structure, everyone was loyal to somebody: there were Parpiyev's people, Gadoev's people, Azimov's people. If you wanted to govern effectively in such conditions, you had to develop your own unique tactics. When Parpiyev came to the Tax Committee, he asked everyone to submit letters of resignation. He said he was going to put a new team together. They all handed in their resignations. Then Botir Rahmatovich sat down, set up calls to everyone he wanted for each position and put together an entire recruitment map for the Committee. Incredible!

It always amazed me how Parpiyev's deputy would kill all of his directives right off the bat. I was «Parpiyev's man». At that time, I was already working for the State Tax Committee press service.

«What are you here for?», «Why do we need that?» were the rhetorical questions Gadoev would ask every time I came in to see him, even if it was about something urgent. He wouldn't offer any help either, of course.

We planned to release a photo album book celebrating the sixteenth anniversary of Uzbek independence. It was to include all the changes and achievements that had been made both in the department and in taxation at large. A working group was set up, with me at the helm; the only snag was that I had no official authority. So, there I am running around, collecting information, trying to get people to bring me statistics, and everyone is just fobbing me off, ignoring me or, if they did give me something, it invariably turned out to be completely useless.

I decided to go and see Parpiyev. The album was all but finished, there were just a few bits and pieces we needed to add.

«Get this book finished sharpish, I want to show it to the President in a few days» he said. He then called Gadoev and told him to help me; «I'm on it» came the reply.

I went up to Gadoev.

At one of many State Tax Committee staff meetings.

«What on Earth are you thinking? How can we have a book ready in four days? Who writes a book in four days?»

«Erkin Fayzievich» I said, «It's almost ready, I just need…»

Gadoev wouldn't listen to what I needed. Instead, he started to grumble and talk down to me in his usual manner. He didn't give me any information either.

That's what it means to be between the devil and the deep blue sea. Later, the bigwigs would work things out between themselves, and I'd be left out in the cold. I'd be the one to blame, naturally, of that I had no doubt. Anyone can be destroyed and replaced in this world. What does that mean for a nobody like me? It truly was scary, I felt like a little fish caught between two huge whales that can't even sense my presence. One thing that made Parpiyev unique was that he never forgot anything and was able to monitor every hour of every day whether things were getting done or not. I told him I was on the case, but nothing was actually getting done.

There was no other option. I had to go and see him.

«Botir Rahmatovich, I won't be able to get the book finished on time. Erkin Fayzievich shouted at me and kicked me out of his office. He says it's a waste of time. What should I do?»

It was clear that the general was extremely annoyed. But he kept silent before issuing a curt: «Go…»

There was a meeting on Monday. I hated all those Monday morning meetings with a passion, and this one even more than usual. I almost overslept because I hadn't got to bed until the early hours. I legged it to work and put on my uniform. The meetings always started on the dot, being late simply wasn't an option.

I sat down, sluggish, blue in the face, with puffy eyes, only half-listening to what the committee president was saying. But I noticed that every time he said something, he would turn to his deputy. He would float an idea and then ask Gadoev's opinion, whereupon Gadoev would delicately and eloquently tear it to pieces.

Then, all of a sudden, Parpiyev banged his fist on the table so hard all the tea pots went flying, jolting us all awake in an instant.

«Erkin Fayzievich, do you think I'm an idiot? You say 'no' to all my directives. You take issue with all my ideas and frustrate all my efforts at reform!»

He stood up, sending his chair flying off to one side. He snapped the pencil he was holding and threw the pieces onto the floor. A deadly hush fell over the room, everybody was on edge.

«Take Allamjonov here!» He scanned the attendees with his eyes until he located me. I gripped my chair tightly and felt a sudden strong urge to visit the toilet. «I told him to make me a book, but you sent him away. Why did you tell him it was a waste of time?»

«I didn't say that, I mean…» – said Gadoev attempting to defend himself. It was obvious that he was terrified.

Parpiyev took off his glasses, threw them onto the table and left the room, slamming the door so hard that the walls shook.

Meanwhile, I stayed where I was, hoping my chair would swallow me up. Gadoev gave everyone a look as if to intimate that the meeting was over. Everybody went their separate ways in silence.

Then he approached me.

«May I talk to you for a second? Where's your office?»

We stepped into my office, and he immediately started backing me into a corner with question after question.

«What did I ever do to you? Why did you set me up like that?»

In an effort to save my skin, I had to think on my feet:

«Erkin Fayzievich, Botir Rahmatovich asked me a question, and I answered it… I said you were concerned that the book wouldn't be good enough if it's written in four days. He asked and I answered, that's all there is to it. He just didn't understand me correctly».

Naturally, he didn't believe me.

The truth – that I had indeed set him up big time – became apparent a few minutes later. Everyone received a message telling them to go to their offices and that nobody was to leave. We stayed in the building well into the evening, in our offices. The president, on the other hand, did not. As I later realised, that was to prevent any information from leaking out. To make sure Gadoev couldn't muster his men, tanks and heavy artillery.

The very next day Prime Minister Shavkat Miromonovich Mirziyoev13 came for a meeting and Gadoev was relieved of his position. However, he had been first deputy for many years and had still managed to rouse his tanks into action. They kept him on as Deputy President of the Committee and Chancellor of the The Academy14; he just left the State Tax Committee and stopped interfering in our internal business.

In his place came current Deputy Prime Minister Behzod Anvarovich Musaev. The liberal wing of our political landscape. He was an easy man to work with.

Then came my turn to give up working for the State Tax Committee, and indeed government service altogether. The decision was neither spontaneous nor long-considered, simply the only option I had.

In every government department that Botir Rahmatovich ran, he wrote the agendas of the weekly meetings himself. They were nothing like the typical get-togethers with boring reports that were over in a flash and then back off to work you went. Every single one was an inquisition. His aides would prepare questions for every department with the potential to really trip up their respective heads. Information was collected, which Parpiyev would then distribute at the meeting. Whoever took to the podium to give an account of what their department had achieved was taking a big risk. All the department heads would resort to cunning and ask Dilshod Turahonov not to include their division in the order of business. Perhaps they paid him not to, I don't know. The end result was that I tended to be the one who took the podium and suffered on everybody else's behalf. But the General wasn't about to feel sorry for me. Meanwhile, Chief of Staff Dilshod Turahonov had taken a particular disliking to me and tried to make me look a fool every time.

In the end, I'd had enough of it all. Surely there were other issues of importance in the Tax Committee besides me? I put together a reporting schedule that included all the departments, even the chancellery (the only exception was security), took it to Parpiyev and told him that the meetings had been far too one-sided of late. Let everyone give their reports one by one, every department should be able to demonstrate its work. He agreed and signed the document.

After that, whenever they dragged me up onto the podium, I would talk about everyone who wasn't doing their job. As a result, my esteemed colleagues decided to move me to «Turahonov's list», so that I wouldn't be called up to speak. They probably all chipped in together.

They never forgave me for that move, and I ended up paying dearly for it. They put together some sort of false report. I can't even remember what they accused me of, it was so absurd and unjust. For the first time in nine years, Parpiyev tore me to pieces in a meeting in front of everyone, and I couldn't even defend myself. That's when I realised my time there was at an end.

But I wanted to leave on good terms. Even after nine long years I still hadn't forgotten his first «Wa-Alaikum-Salaam» when I greeted him. The fact that he treated me like a grown-up and not some errand boy. I came

«Let him in» – said Botir Rahmatovich to

The following day, I came to his office and told him that I wanted to leave to start my own business.

«Are you upset about something?» – he asked.

«No, of course not! What would I have to be upset about?»

«You're upset…» said the General. «I can tell. Go on then, give me your resignation. Best of luck to you».

I left, but to this day I'm still eternally grateful to Botir Rahmatovich for the life lessons and the discipline he taught me. To always roll with the punches and believe in the impossible. And that there's no such thing as «can't». Come to think of it, he basically raised me as if he really was my uncle.

Anyway, off I went into business, where I earned my first million. I had been trying to make money since I was a young boy, but it hadn't always worked out.

1 NTRK – National Television and Radio Company.

2 DAVR – collage of informational programmes produced for NTRK's Yoshlar channel.

3 Somsa – baked uzbek dish similar to patty with meat.

4 Emergencies Ministry – Ministry of Emergencies of the Republic of Uzbekistan.

5 Abdusaid Kuchimov – Uzbek journalist, President of the National Television and Radio Company of Uzbekistan from 1997-2005.

6 Beruni – the last station on the Oʻzbekiston line of the Tashkent metro.

7 Karakamysh – an area in the Almazarskiy district of Tashkent.

8 Kurpacha – uzbek mattresses with cotton filling.

9 Tashkent State University – Tashkent State University, renamed in 2000 to the «Mirzo Ulugbek National University of Uzbekistan».

10 Uzmetronom – an independent website in Uzbekistan. Blocked until May 2020.

11 Zhemchug – experimental building in Tashkent which houses the famous Zhemchug store.

12 SHARK – a publishing company.

13 Shavkat Mirziyoyev – from December 2003 to December 2016, Shavkat Mirziyoyev held the position of Prime Minister of the Republic of Uzbekistan. Then, from 14 December 2016 to the present day, he has been the President of the Republic of Uzbekistan.

14 The Academy – Tax Academy of the State Tax Committee.

III

Sugar, a Bath,

a Press, and

a Measuring Jug

During the nineties, our family wasn't rich, but at least we had stability. Mum was a midwife and dad was a car mechanic; children were constantly being born and cars were constantly breaking down, which meant my parents were always in demand. My parents’ greatest wish was to give their children a good education. That's why when I reached sixth form, mum transferred me to the gymnasium at Tashkent State University, which later went on to become an academic lyceum. She made the transfer without paying any bribes, she simply didn't know that you were expected to.

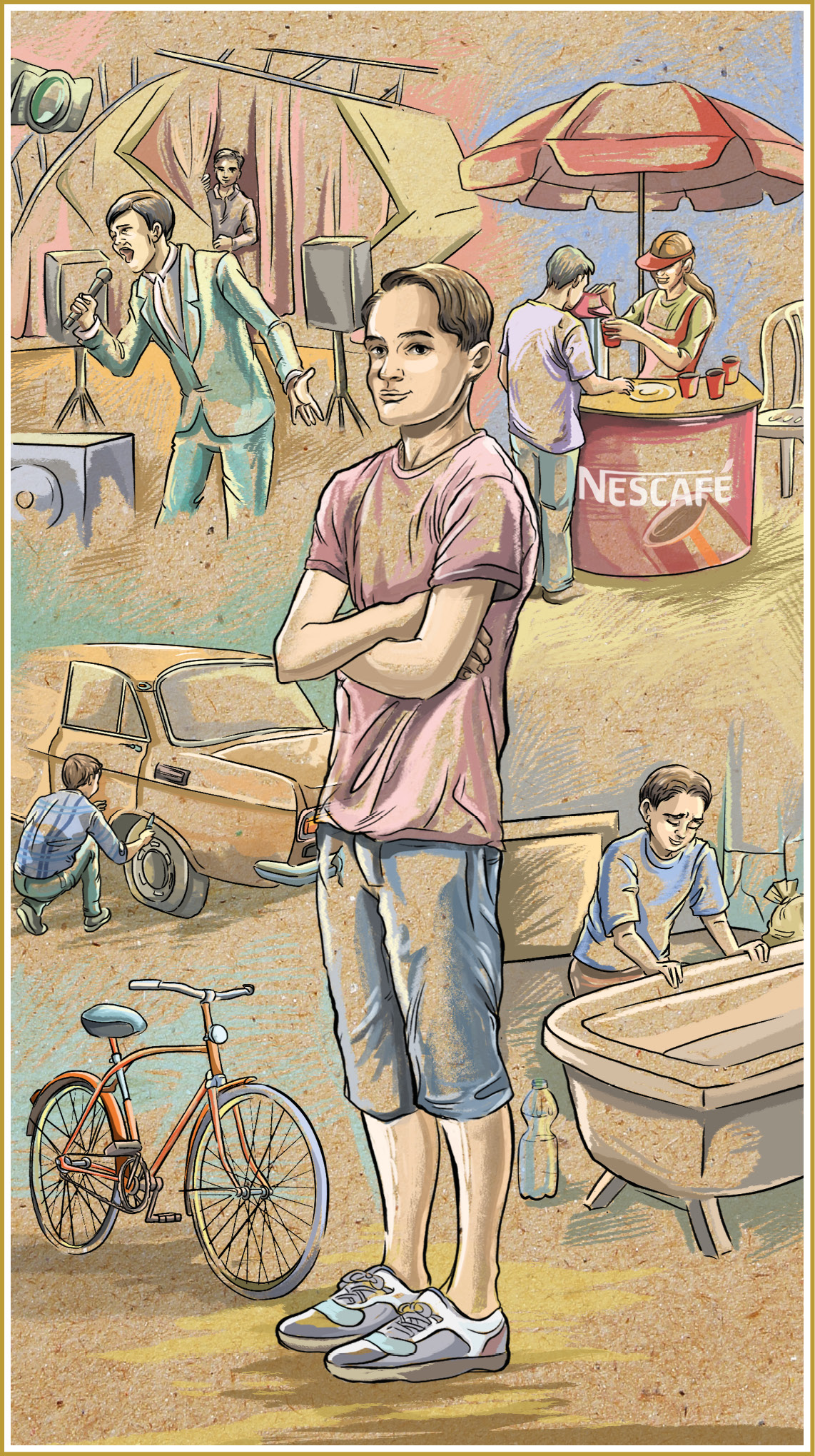

Money is a remarkable thing, and it had always fascinated me. I'll start by saying that I had no intention of living like everyone else, from paycheck to paycheck. I was utterly convinced that when I grew up, I'd have lots of money and would be able to buy myself anything I wanted. The only thing was, I didn't want to wait that long. I wanted to get rich right now and be like the new idols everyone in our neighbourhood looked up to: shopkeepers, tea bar owners, pasta industrialists, popcorn merchants. They had new cars, trainers, jeans, tracksuits – they were on top of the world.

By that time, the communist ideology had completely disintegrated. All our neighbours were talking about was business, about how to make quick, easy money.

We were thirteen and always wanted pocket money. Among my peers, there were many who had part-time jobs. Some used the money to help their families, while others used it to fund their own little dreams. One day I went to work for my cousin at his popcorn factory. I immediately realised that such a life wasn't for me, slaving away all day for a few kopeks.

What did they have me doing there? Well, I had to load the corn into the grinder, then transfer it to a special machine that used high pressure and hot air to pop the corn and turn it into the tasty treat you buy at the shop. They paid you per kilogram of finished product. So you'd think you'd done a boat-full, like ten kilos, but in the end there'd only be half a kilo at most. After calculating the output, my cousin didn't pay me for the work I'd done. When I got home, I put my «earnings» on the table and collapsed on the bed fully clothed, sleeping through to the morning. The following morning, I realised that being a hired hand wasn't my cup of tea.

And it wasn't because the work was hard. It was because you had to work for peanuts while lining someone else's pockets; I could never forgive capitalism for that. I tried making popcorn myself (my friends and I sold it at school). Then, it didn't seem half as exhausting. Because we were working for ourselves. Sure, our popcorn wasn't in particularly high demand. It was always burnt and didn’t taste particularly appealing. That was my first business lesson: you’ve got to have a good product if you want people to buy it.

Thus, at the tender age of thirteen, I decided to become a sugar baron. Then I'd be able to buy myself a bike. No one with a bicycle would let me ride theirs anymore, and my parents had told me firmly: «No bike for you, Komiljon. Even without one, you get up to all sorts of mischief: you've already run away from home and, if you had a bike, how would we ever find you?»

My business plan was as following: buy a sack of sugar, turn it into sugar lumps and sell them for slightly more than I paid. The difference in price would be my profit.

I rented a fully equipped, turnkey sugar processing plant. «Fully equipped turnkey sugar processing plant» makes it sound better than it actually was. In reality, it was an old, abandoned residential building that no one lived in anymore. In terms of equipment, it came with a mill, a press, some plywood board, a bath, a hot air blower and a 1.5-litre measuring jug. First things first, you had to turn the sugar into powder. Then, you had to tip it all into the bath and pour in one and half litres of cold water. The powder would then become crunchy and moist, a bit like snow. Next, you had to squash it down with the press, place the resultant sheet on the plywood board, and then cut out perfectly shaped cubes. Finally, you would dry them in the room with the hot air blower. In the space of a day, you could turn one sack of sugar into the sort of sugar cubes people would buy as presents on national holidays.

Dad's clientele at the garage included many shopkeepers. He also asked his friends to sell my sugar.

My sugar-processing plant was a one-man band: I was simultaneously the workforce, the cleaner, the delivery boy, and the CEO. Before I leased the plant, I offered my friends the opportunity to be my partners, but they refused. They probably made the right decision as, two weeks later, my business was rocked by its first financial crisis. Granulated sugar suddenly disappeared from the markets and then, when it returned, was more expensive. That meant that the small difference in price that had allowed me to a make a profit was now gone. But the interesting thing was that my friends hadn't refused because they saw the crisis coming, but rather because they couldn't be bothered and didn't see the point. We had grown up together, but now our outlooks on life were poles apart.

Now, I'm not saying that everybody should pursue wealth. There are some people who genuinely don't need it and who have their own dream to follow. People have all sorts of dreams and aims; they might want to be a doctor, a mountain climber, a pilot, a traveler, a journalist, or a writer. For the new generation of such children, money is becoming more and more of an inconvenience. However, if your aim is to get rich, then just one dream and an education is not enough. You need to have a good work ethic. If you're not willing to go all in on your business, it's best not to bother starting one. Enterprise is not for the lazy.

I wasn't lazy. I was just unlucky with the economic situation and didn't manage to make it as a sugar baron. But I never gave up trying to get ahead. I found it interesting, the process itself, exercising self-control over money, organising my own business. And the failures only made my desire to succeed stronger.

Anyone who remembers the nineties will agree with me. The economic and political situation in the country was very interesting indeed. We were suddenly presented with a whole host of ways to make money. You were no longer a black marketeer, you were an entrepreneur. Like mushrooms after rainfall, pharmacies, pool halls, saunas, and retail shops started popping up. It was unbridled freedom to do whatever you wanted.

With a classmate after a concert at the Palace of Culture.

But at the same time, following the shattering of communist ideals, there was no clear idea of what direction the country ought to be headed. It was also a time that saw immense growth in religious extremism. Many people became borodachi («bearded ones») of the sort Karimov was constantly fighting. It was a truly anxious time, filled with terrorist acts, explosions, and the like. And the government's official ideology became Musaffo osmon1. It stated that the most important thing was that the sky above us should be peaceful and there ought to be no war. As an idea, it wasn't bad, but it didn't fit with the emergence of the super-rich. The country's government was concerned that this new class could threaten the peaceful status quo. By all means, earn money, but don't get too big for your boots. You can buy yourself a car, a home, even keep a stash of gold in your biscuit tin, just don't have ambitions of becoming an oligarch.