Полная версия

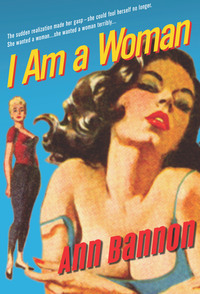

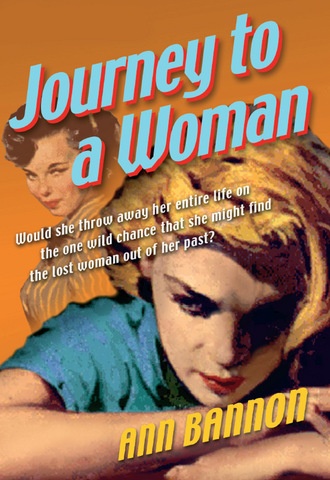

Journey To A Woman

“Some good-timer, backslapping sort of guy. A roommate of Cleve’s once, before I knew him. Younger than Vega. It’s only been two years since she divorced that one. I guess he didn’t get past the bedroom door either, but he did get into her bank account. Spent all her money and then disappeared. Nobody knows where he is. She never talks about him.”

“Well,” Beth said cautiously, “that’s not so strange. I mean, she obviously wasn’t a good marriage risk, but lots of women have behaved that way. Maybe the men she picked weren’t such prizes either.”

He shrugged. “Maybe.” He turned to look at her. “She lives alone with her mother and her grandfather. Cleve says they’re a trio of cuckoo birds. You can’t get him over there. Except Christmas and birthdays, and he only goes because he feels he has to.”

“Do they really hate each other—Cleve and Vega?” Beth asked.

“Only on the bad days,” he said. “Now and then they quit speaking to each other. But then their mother breaks a leg or Gramp poisons the stew and they get back together. Takes a family calamity, though. Right now they’re as friendly as they ever are, according to Cleve. I don’t know why it should be that way. Doesn’t seem natural.”

“They’re both such nice people. It’s a shame,” she said.

Charlie couldn’t stand to look at her any longer and not touch her. He put his arms around her and felt her nestle against him with a shattering relief. After a few minutes he heaved himself over her to turn out the dresser lamp, returning fearfully to her arms, only to find them open.

“Is this my thanks for giving in?” he said. It was flat and ironical. He couldn’t help the dig. But she took it in stride by simply refusing to answer him. He made up for several weeks of involuntary virtue that night.

Before they slept, Charlie had to say one last thing. He saved it until he knew they were both too tired to stay awake and argue. He didn’t want to ruin things. She lay very close to him, in his arms, too worn out for her usual tears of frustration, and he whispered to her, “Beth?”

“Hm?”

“Darling, I have to know this. Don’t be angry with me, just tell the truth like you did earlier. Beth, I—” It was hard to say, so awkward. He was afraid of humiliating her, rousing her temper again. “I keep thinking of Laura,” he said at last.

“Laura?” Beth woke up a little, opening her eyes.

“Yes. I mean, I can’t help but wonder if you—you know how you felt about her—if it’s the modeling that interests you or if it’s—Vega.”

In the blank dark he couldn’t see her face and he waited, fearful, for her answer. God, don’t let her explode, he prayed.

Beth turned away from him, her face dissolved in tears. “It’s the modeling!” she said in a fierce whisper. And they said no more to each other that night.

Chapter Five

VEGA’S STUDIO WAS LOCATED ON THE SECOND FLOOR OF A building that housed an exclusive dress shop and a luggage and notions shop. It was an expensive place to rent and Beth was rather surprised to see how bare it was. There was a small reception room which was tastefully decorated, though there was space for more chairs in it. There was a door marked “office,” which was closed, and there was a large, nearly empty studio room with eight or ten folding chairs, the kind you sit on at PTA meetings.

Beth peered into the studio hesitantly, and instantly Vega materialized from a small group of high school girls who had surrounded her while she spoke to them. There was silence while she walked, regally lovely in flowing velvet, both hands extended to Beth. The teens examined the newcomer with adolescent acuteness, and Beth took their silent appraisal uneasily.

Vega reached her. “Darling, how are you?” she said in her smooth controlled voice, and kissed Beth on the mouth. Beth was shocked speechless. She stared at Vega with big startled eyes.

“Oh, don’t worry,” Vega laughed, seeing her expression. “The doctor says I’m socially acceptable. The TB has been inactive for almost two years—really a record.”

But it wasn’t the infected lung, the possibility of catching TB, that upset Beth. That, in fact, never occurred to her. It was the sudden electric meeting of mouths, the impudence of it, the feel of it, the teen-aged audience taking it all in. Beth was piqued. Vega had no business treating her so familiarly. Still, it was impossible to make a fuss over it, as though she were guilty of some indecent complicity with Vega.

“How are you?” she said uncertainly.

The knot of girls began to talk and giggle again, and Vega turned to them. “Okay, darlings, you can go now,” she said. “That’s all for this afternoon.”

She took Beth’s arm and led her into the studio while the girls filed past them and out, still staring. Beth began to be seriously disturbed. Vega behaved as if they were sisters, at the very least, and at the worst … Beth turned to her abruptly.

“Vega, I hate to say anything, but really, I—I—” She paused, embarrassed. Vega would surely take it the wrong way. Who but a girl with a problem would take the kiss, the familiarity, so hard? What, after all, was so dreadful about a kiss between two women? Even if it was so unexpected, even if it was so direct that a trace of moisture from Vega’s lips remained on Beth’s own.

I’d only look like a fool to complain, Beth thought. She’d think I was—queer—or something. How she hated that word!

“Something wrong?” Vega said helpfully.

“I—well, I’m just not so sure I should do this, that’s all,” she said lamely. “Charlie said—”

“Charlie be damned. Charlie’s as stuffy as Cleve. They make a beautiful couple,” she shot at Beth, who was startled by the sharp emphasis. “However …” Vega turned away, walking to one of the folding chairs to pick up her purse and fish out a cigarette. “Maybe he’s right. Maybe you shouldn’t try to do this.”

“What?” Beth exclaimed. “After all you said—”

“Oh, just for today, I mean,” Vega laughed. “I don’t feel much like giving another lesson. I get so sick of this damn place,” she added plaintively, and her change of expression impressed Beth. Vega looked tired for a moment, and perhaps not as young as usual. But her face smoothed out quickly. “You don’t really mind, do you?” she said.

“Well, I—I do a little,” Beth admitted. After what she had gone through to get Charlie’s approval she minded a lot. But Vega intimidated her somehow, and she hadn’t the nerve to show her irritation. “But if you’re tired …” She paused.

“I am,” Vega said. “But I have no intention of abandoning you, my little housewife.” She swung a plush coat over her shoulders. “I’m tired and fed up and sick to death—not really,” she added with a brilliant smile that did not reassure Beth at all. The edge in Vega’s usually soft and low voice made her words sound literally true. Tired, fed up, sick. And those eyes, so deep and dark and full, had turned lusterless again, as if Vega were defying her to look into them and see her secrets.

“Let’s go slumming,” she said, and the way she said it, the quick return of life to her face, the odd excitement so tightly controlled, was infectious.

“Where?” Beth said, intrigued.

“Well, you look so nifty we can’t go too far astray,” Vega said, looking at her professionally. And yet not quite professionally enough. “Do you have your car?”

“Yes.”

“Good. I’ll show you where my girls hang out. My teenagers.” She spoke of them with visible affection. “It’s a caffè espresso place—The Griffin. It’s not far. Have you been there?”

“I’ve heard of it but I never thought I’d see it. It’s the last place in Pasadena that would interest my adventurous husband.”

“Let’s go!” Vega spoke gaily and caught Beth’s arm. They left the studio together, walking down the narrow flight of stairs to the street, and Beth thought, My God, I never even got my coat off.

“I like your studio, Vega,” she said, because the silence between them was becoming too full.

“Do you?” It was almost a listless response. “I’m going to redecorate it. That’s why it looks so bare.”

Beth tried to look at Vega’s face but they had reached the foot of the stairs and she had to pull the door open for her instead. Vega would not release her arm, even through the clumsy maneuver of getting out the door, and Beth was peeved to find her clinging to her still as they walked down the street toward the car. She was grateful when they reached it for the semi-privacy it afforded.

“Where to?” she said, starting the motor.

The Griffin was dark and dank, jammed with very young, very convivial people very sure of themselves. In a corner an incredibly dirty minstrel twanged on a cracked guitar and sang what passed for old-English ballads. There were beards aplenty on the males and pants aplenty on the girls. Only a few females, Vega and Beth among them, wore skirts. And there was coffee of all kinds but no liquor. Not even beer.

“Coffee—that’s all you can get in here,” Vega said. So they ordered Turkish coffee and drank it while Vega told her about the place. “It’s just an old private house,” she said. “The kids have redone it all themselves.”

“They did a godawful job,” Beth commented and immediately sensed, without being told, that she had injured Vega, who seemed actually rather proud of the place.

“Yes, I guess they did,” she admitted. Vega looked around, her eyes bright and probing, wafting smiles at the familiar faces and studying the strange ones. Beth saw her nervous pleasure, her fascination, quite plainly in her face. So it startled her to see that same lovely face cloud over abruptly, with angry wrinkles spoiling the purity of her brow. Vega glanced at Beth and realized her emotions were showing. Rather diffidently she nodded at a tableful of girls about ten feet from them.

“See those girls?” she said. There were five of them, all in tight pants, all rather dramatically made up, with the exception of one who wore no makeup at all. Her hair was trimmed very short and she had a cigarette tilting from the corner of her mouth. Beth’s gaze rested on her with interest. She looked tough, a little disillusioned. Her blonde hair was unkempt but her eyes were piercing and restless and her face made you look twice. It wasn’t ugly, just different. Quite boyish.

“They’re disgusting,” Vega said. “I can’t bear to look at them.”

Beth saw her hand trembling and she looked at her in astonishment. “For God’s sake, why?” she said. “They’re just kids. They look pretty much like the others in here. What’s so awful about them?”

“That one with the cigarette—she ought to be in jail,” Vega said vehemently.

“Do you know her?” Beth said, glancing back at the tough arresting face. Vega’s heat amused and scared her a little. Vega was so frail. How mad could you get before you hurt yourself, with only one lung, a fraction of a stomach, and a bodyful of other infirmities?

“I don’t know her personally,” Vega said, stabbing out her cigarette, “but I know enough about her to put her in jail ten times over.”

“Why don’t you, then?” Beth asked.

Vega looked away, confused. Finally she turned back to Beth and pulled her close so she could whisper. “That lousy bitch is gay. I mean, a Lesbian. She hurt one of my girls. Really, I could kill her.”

“Hurt one of your girls?” Beth could only gape at her. What did she mean? She sounded tense, a little frantic.

“One of my students. She made a pass at her,” Vega fumed.

“Well, that couldn’t have hurt very much,” Beth said and smiled. “That’s not so bad, is it?” She looked curiously at the girl.

But Vega was displeased. “I don’t imagine you approve of that sort of thing?” she said primly, and Beth, once again, was lost, surprised at the changes in her.

“I wouldn’t send her to jail for it,” Beth said.

Vega stared at her for a minute and then she stood up. “Let’s go,” she said. “If I’d known she was in here I wouldn’t have come.” She was so upset, so obviously nervous, that Beth followed her out without a protest. They walked to the car, neither one speaking.

“Take me home, will you, Beth?” Vega said when they got in, and lapsed into gloomy silence. Beth began to see what Charlie meant by strange. Moody and restless. In fact, Vega’s mood had changed so radically that the bones seemed to have shifted under her skin. Her face looked taut and tired and much older now. She slumped as if weakened by her angry outburst.

At last Beth asked softly, “Why do you go in there, Vega, if it bothers you so?”

“I didn’t expect her.”

“What did you expect?”

“My girls, of course. They’re in there all the time.”

And Beth could hear, in the way Vega said “my girls,” how much her students meant to her, how much she needed their youth around her, their pretty faces, their respect. “I like to let them see me in there once in a while,” she added, trying for a casual sound in her voice. “Gives them the idea that I’m not a square. You understand. You see—I mean, well, they mean a lot to me,” she went on, and there was a thread of tense emotion in her voice now. “Everything, really. They’re all I have, really, I—” And unexpectedly she began to cry. Beth was both concerned and dismayed. She reached a hesitant hand toward Vega to comfort her, controlling the car with the other.

“It’s all right, Vega, don’t cry,” she said. “Do I turn here?”

Vega looked up and nodded.

They turned down the new street and Beth ventured softly, “You have your mother and grandfather, Vega. And Cleve. Your family. You aren’t alone. And you have friends.”

“My family is worthless! Worse than worthless. They hang like stones around my neck,” Vega said and the bitterness helped her overcome her tears.

“I’m sorry. I should keep my mouth shut,” Beth said.

“And I haven’t any friends,” Vega cried angrily. “Just my girls. They’re sweet to me, you know, they bring me things—” and abruptly, as if she was ashamed, she broke off. “I’d like you for a friend, Beth,” she said. “I really would. I liked you right away. I’ve never been much good at making friends with women, and for some reason I get the feeling that you’re the same way. It makes me feel closer to you. Am I right?” She paused, waiting for an answer.

Beth was alarmed by her behavior, afraid to aggravate her, and yet she felt it served her as warning not to get too close to Vega. The older woman was lovely, quick and charming. But Charlie was right—she was strange. Beth had a premonition of that wild fury with the world that displayed itself against the Lesbian and against Vega’s family turning on herself someday. But she couldn’t delay answering. You offer your friendship gladly, without deliberation, or you don’t offer it at all.

“I’d like to be friends with you, Vega,” she said, but it sounded hollow to her.

To Vega it sounded beautiful. “I’m glad,” she said, and Beth felt that the mood had passed. Vega put a hand on her arm and left it there until they reached her house.

“Come in for a cocktail,” she said. She was telling Beth, not asking her, and Beth was unable to refuse. “There’s just one thing,” Vega cautioned as they walked up the driveway to the small bungalow. “Mother can’t drink anything. But anything. Really. It would kill her. She’s an absolute wreck. You’ll love her, of course, but she is a mess. I sometimes think she just keeps on living to remind me of the powers of alcohol.”

Beth blanched slightly at this, but Vega laughed at her own remarks. “Anyway, Mother drank like a fish for twenty-three years and suddenly she went all to hell inside. Liver, bladder, God knows what-all. The doctor tried to explain it to me, but all I know is she aches all over and she has to make forty trips to the bathroom every day.”

The little crudity brought Beth up short. It was so homely, so out of place on Vega’s patrician lips. But Vega was full of contradictions; they were, perhaps, her only consistency.

As they paused, they were approached abruptly by a slight shadow of a man in worn corduroys and a jaunty deer-hunting cap. His arms were full of cats and his eyes full of mischief. What cats couldn’t find room in his arms sat on his shoulders.

“Gramp!” Vega exclaimed. “You scared me to death.” She relieved him of two cats, the ones that were having the most trouble hanging on. “This is Beth Ayers,” she told him. “Beth—my grandfather.”

“How do you do, Mr.—?” Beth began clumsily, holding out a hand to him.

“Gramp. Just call me Gramp.” He ignored her hand. Even with two of the cats transferred to Vega’s arms he was still too loaded to let go and pursue the normal courtesies. “My best friends,” he grinned, nodding at the soft animals.

“Your only friends,” Vega amended. “The only ones he trusts, anyway,” she told Beth. “We were just going in for a cocktail, Gramp. I was telling Beth about Mother.”

“What about her?” His eyes snapped with good-humored suspicion.

“Just what a mess she is.”

“Well, forewarned is forearmed,” he said to Beth. “She’s really quite harmless.”

“Except for her tongue,” Vega said softly.

The three of them headed for the front door again. “Fortunately she’s much nicer than she looks,” Gramp explained. “She likes to laze around in nothing but an old beat-up bathrobe. Saves pulling down her pants all the time. You see, she has to take a—”

“I know, I know, Vega told me,” Beth said quickly. Why did they take such a delight in exposing all the ugly comical little family weaknesses to her? Did it make them easier to bear? Or were they punishing themselves for something? Beth stopped where she was.

“What’s the matter?” Vega and Gramp asked with one voice, pausing and looking back at her.

“Vega, your mother doesn’t want any visitors,” Beth said. “She’s sick.”

“Sure she’s sick. We’re all sick. It’s part of the family charm,” Gramp said. “Come on in and join the fun.”

“You’ll see what I’m going to look like in another ten or twelve years, according to Mother,” Vega said.

“The last thing she’d want is visitors,” Beth tried once more, but Vega shushed her with a laugh.

“Bull,” Gramp commented. “Hester’s sick and proud of it. She likes to show it off. She gave up appearances years ago. Actually takes pride in being a wreck. She’s delightful. You’ll love her. Even the cats enjoy her company.”

And Beth, reluctant, bashful, but overwhelmed with curiosity to see what Vega would “look like in ten years,” followed them in.

“Don’t mention liquor,” Vega hissed just before she pushed the front door open. “Remember.”

Beth’s first impression was that the house was stiflingly hot; and the second, that it was jam-packed with rickety furniture. Vega flitted around the room lighting lamps and dissipating the gloom, and Beth suddenly became aware of an old woman sitting in a corner who appeared to be broken into several pieces. She wore a gray, once-pink dressing gown; she had been listening to a speaking record until she heard Vega and Beth enter. Vega kissed her head briefly in salutation.

“Mother, this is Beth Ayers,” Vega said “I told you about her. Mother’s blind as a bat,” she said cheerfully to Beth, who advanced to take the old lady’s outstretched hand. “I forgot to tell you that.”

“But not much else, hey?” her mother said, holding out a hand. “How do you do, my dear?”

Beth murmured something to her, grasping her hand gingerly. And then Vega said, with a wink at Beth, “Let’s all have a Coke. Mother, you game?”

“Are you kidding?” Mrs. Purvis said. “It’ll have to be Seven-Up, though. Gramp busted the plumber one with the last Coke. There’s still fizz all over the john.” And she cackled with pleasure. Gramp, unperturbed, was arranging himself in a harem of cats on the couch. Beth stared at Mrs. Purvis, repelled and fascinated and amused.

Vega in ten years? Utterly incredible! Never.

“What the hell did you do that for, Gramp?” Vega called from the kitchen. “The plumber hurt one of the cats?”

“No, they disagreed about the plunger,” her mother answered, cutting Gramp off. “Gramp said the head was German rubber and the plumber said they don’t make rubber in Germany. So Gramp pickled him in fizz.”

“He deserved it. He was wrong,” Gramp said mildly.

Beth smiled uneasily at them all, slipping out of her coat and feeling the sweat already trickling down her front. God, it must be a hundred degrees in here, she thought. How does Vega stand it?

Vega came out of the kitchen, apparently standing it very well, with some glasses on a tray and a bottle of Seven-Up. She poured it for her mother and handed Beth a glass with two inches of whiskey and an ice cube in the bottom. Gramp got the same and settled back into the cats with a conspiratorial sigh.

“Tell us what you did today, Mother,” Vega said, while Beth made signs to her that she wanted some water in her drink. Vega took the glass back to the kitchen while Mrs. Purvis answered.

“Listened to a book,” she said.

“A good one?”

“Good book, but a lousy reader. They cut out all the good stuff anyway. I guess they figure we poor blind bastards will die of frustration if we hear the good parts.” She chuckled. “With me it’s all a matter of nostalgia, anyway,” she added. “How old are you, Beth, my dear?”

“Thirty,” Beth said, taking her glass again from Vega.

“On the nose? Any kids?”

“Two,” Beth said. “Boy and girl.”

“Ideal,” said Mrs. Purvis. “Just like the Purvis clan. You know,” she said, leaning toward Beth, “what a harmonious family we are.” There was a mischievous leer in her smile.

“I’m sure you are,” Beth said politely.

Mrs. Purvis roared amiably. “Everything we ever did was immoral, illegal, and habit forming,” she said. “Until Cleve turned straight and earned an honest living,” she added darkly.

“God, Mother, you make us sound like a pack of criminals,” Vega protested.

“We’re all characters. But not a queer one in the bunch.” Mrs. Purvis took a three ounce swallow of Seven-Up. “Too bad you never knew my husband,” she said to Beth. “A charmer.”

“Daddy was a doctor,” Vega said, and Beth noticed, uncomfortably, that she was working on a second drink of straight whiskey.

“Yes,” said Mrs. Purvis energetically. “Specialized in tonsils. Once a week he went down to his office—Monday mornings, usually—and sliced out eighteen or twenty pairs. That was all. Never did another thing and never lost a patient. Made a pile too, all on tonsils. Kept us quite comfortably for years. It’s a shame he wasn’t around to carve Vega up when the time came.”

“My tonsils are the only things they didn’t cut out, Mother,” Vega reminded her.

“Well, it was a good life,” Mrs. Purvis said. “Lots of leisure time, lots of money for booze and the rest of life’s necessities. Of course, I drink tamer stuff these days. How’s your Seven-Up, girls?”

“Oh, it’s delicious,” Beth said quickly, but something in the old lady’s face told her that Vega’s silent boozing didn’t escape her mother. Whiskey didn’t sound any different from Seven-Up, but it smelled different.

“I hope you split them up fairly, Vega,” Mrs. Purvis said. “There were only two.” She smiled inwardly at herself, slyly.

“There were three, Mother. One in the back of the shelf. You missed it,” Vega lied promptly, with perfect ease.

“Oh.” Her disappointment seemed to remind Mrs. Purvis that it was time for another of her incessant trips to the bathroom, and she heaved unsteadily to her feet.

“Can I help you?” Beth exclaimed, half rising, but Mrs. Purvis waved her down.

“Hell no, dear,” she said. “This is one thing I can still do by myself, thank God. When I can’t make it to the john anymore I’m going to lie down with the damn cats in the backyard and die.”

“If they’ll have you,” Gramp murmured.

“Besides, she needs the exercise,” Vega said. “It’s the only walking she does, really.”