Полная версия

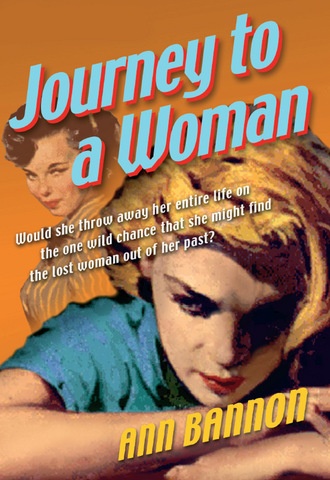

Journey To A Woman

“ ’Bye, honey,” he said into her ear, and blew into it gently.

“Have a good day,” she said absently.

He wished gloomily that she would see him to the door.

“Daddy, when you get home will you make me a kite?” Skipper said suddenly. He was five, just a year older than his sister, and he looked very much like Beth.

“Sure,” Charlie said, still looking at the short dark curls on the back of his wife’s head. He stroked her neck with his finger.

“Yay!” Skipper cried.

Beth squirmed slightly, irritated by Charlie’s wordless loneliness and a little ashamed of herself. Charlie left her finally and went toward the front door, slipping into his suit coat as he went. Beth felt his gaze on her and glanced up suddenly with a little line of annoyance between her eyes.

“Something wrong?” she said.

“No. What are you doing today?”

“I’m flying to Paris,” she said sarcastically. “What else? Want to come?”

“Sure.” He grinned and she softened a little. He was handsome, in a lopsided way, with his big grin and his fine eyes. The kids set up a clamor. “Can I come too? Can I come too, Mommy?”

And when Charlie went out the door he heard her shout at them in that voice that scared him, that voice with the edge of hysteria in it, “Oh, for God’s sake! Oh, shut up! Honest to God, you kids are driving me insane!”

And he knew she would slam something down on the table to underline her words—a jam jar or a piece of tableware, anything handy.

He drove off to work with a worried face.

Chapter Two

BETH LOVED HER KIDS THE WAY SHE LOVED CHARLIE: AT A distance. It was a real love but it couldn’t be crowded. She had no patience with intimacy. The hardest years of her life had been when the two babies arrived within eleven months of each other. One was bad enough, but two! Both in diapers, both screaming and streaming at both ends. Both colicky, both finicky eaters.

Beth was completely unprepared, almost helpless with a screaming nervousness that put both Charlie and the kids on edge. She never quite recovered from her resentment. A few years later, when the worst was over, she began to wonder if her quick awful temper and desperation had made the children as nervous as they were. She blamed herself bitterly sometimes. But then she wondered how it could have happened any other way.

But when Polly shut herself in a closet and cried all afternoon, or Skipper threw a tantrum and swore at her in her own words, or when Charlie sulked in angry silence for days on end after a quarrel, she began to wonder again, to accuse herself, to look wildly around her for excuses, for escape.

Beth had just one friend that she saw with any regularity, and that was the wife of Charlie’s business partner. Her name was Jean Purvis, and she and Beth bowled together on a team. Beth had been searching for ways to get out of it since she had started it. Bowling bored her and so did Jean. But you couldn’t help liking the girl.

Jean Purvis was a good-hearted person, a natural blonde with a tendency to plumpness against which she pitted a wavering will power. She had two expressions: a little smile and a big smile. At first Beth envied her sunny nature, but after a while it got on her nerves.

She must have had days like other people, Beth thought. She must get mad at her husband once in a while.

But if Jean ever did it never showed and her eternal smile made Beth feel guilty. It was like an unspoken reproach of Beth’s sudden wild explosions and cloudy moods, and it made her resent Jean; it made her jealous and contemptuous all at once.

Jean Purvis and her husband Cleve were the only people that Beth and Charlie knew when they first moved to California. Cleve and Charlie were business partners now, manufacturing toys, and it had been Cleve’s drum-beating letters that encouraged Charlie to give up his law apprenticeship and move to the West Coast.

Beth reacted angrily at first. “I like the East!” she had exclaimed. “What do I know about California? Everybody in the country is headed for California. It’ll be so crowded out there pretty soon they won’t have room for the damn palm trees.”

“Cleve has a good start in business,” Charlie said.

“Charlie, what in God’s name do you know about making toys? I’d be glad if you’d make one decent slingshot for Skipper and call it quits,” she told him.

But his stubborn head was already full of ideas. “One craze, one big hit—we’d strike it rich,” he said. “One Hula Hoop, one coonskin cap, something like that.”

“You sit there like a grinning happy idiot ready to throw your whole career, your whole education, out the window, because your old fraternity buddy is making plastic popguns out in Pasadena and he says to come on out,” Beth cried, furious. “I don’t trust that Cleve Purvis anyway, from what I’ve heard about him. You always said he was a heavy drinker.”

But he had made his mind up, and with Charlie that was the same as doing a thing. He could not be moved.

Charlie left Beth and the two babies in Chicago with her uncle and aunt while he went out to Pasadena to join Cleve and find a place to live.

Beth loved it. Her Uncle John was fond of spoiling her. Beth was his daughter by proxy; he had no children of his own. She had been dumped in his lap, sobbing and runny nosed and skinny at eight years, when her parents were killed. Miraculously, she had learned to love him and he returned her love. With Aunt Elsa it was all a matter of keeping up good manners, and she was automatically friendly.

For four months Beth slept and ate and lazed around the house. It was delicious to be waited on, to have civilized cocktails in the afternoon, to let somebody else pick Polly up when the colic got her. To go out for whole evenings of food and glittering entertainment and know there were a dozen capable baby-sitters at home. Beth refused to join her husband in California until she threw him into a rage.

She realized with something like a shock that she didn’t miss Charlie’s love-making at all. She missed Charlie, in a sort of pleasant blurry way, and she loved to talk about him over a cold whiskey and water, laughing gently at the faults that drove her frantic when they were together. But when she heard his anger and hurt on the telephone it came to her as a surprise, as if she would never learn it once and for all, that a man’s feelings are urgent, even painful. She remembered feeling it like that once, long ago, in college. Was it Charlie, was it really Charlie that did it to her? Or was it somebody else, somebody tall and slight and blonde with soft blue eyes, who used to sit on the studio couch in their room at the sorority house and gaze at her?

Charlie was in a sweat of bad-tempered impatience when she finally, reluctantly, agreed to come out and resume their marriage.

Marriages would all be perfect if the husband and wife could live two thousand miles apart, she thought. For the wife, anyway.

And Charlie missed the kids. “He misses them!” she cried aloud, sardonically. But she knew if they were far away she would miss them too. She would love them at her leisure. They would begin to seem beautiful and perfect and she would forgive them their dirty diapers and midnight squalling sessions.

It scared her sometimes to think of this streak in herself; this quirk that made her want to love at a distance. The only person she had ever loved up close, with an abandoned delight in the contact, was … Laura. Laura Landon. A girl.

Charlie drove her home from the International Airport in Los Angeles. He was bursting with excitement, with things to say, with kisses and relief and swallowed resentments.

“How’s business?” she asked him when they were all safely in the car.

“Honey, it’s great. It’s everything I told you on the phone, only better. We did the right thing. You’ll love California. And I have a great idea, it’ll sell in the millions, it’s—oh, Beth, Jesus, you’re so beautiful I can’t stand it.” And he pulled over to the side of the road, to the noisy alarm of the car behind him, and kissed her while Skipper punched him in the stomach. He laughed and kept on kissing her and they were both suddenly filled with a hot need for each other that left them breathless. Beth felt a whole year’s worth of little defeats and frustrations fade and she wished powerfully that the children would both fall providentially asleep for five minutes. She was amazed at herself.

They got home after an hour’s driving on and off the freeways. It was a small town just east of Pasadena: Sierra Bella. It was cozy and old and very pretty, skidding down from the mountains, with props and stilts under the oldest houses.

It was quite dark when they drove into their own garage and Beth couldn’t see the house very well. But the great purple presence behind them was a mountain and it awed and pleased her. She was used to the flat plains and cornfields of the Midwest. Below them were visible the lights of the San Gabriel Valley: a whole carpet of sparklers winking through the night from San Bernardino to the shores of the Pacific.

“Like it?” Charlie said, putting an arm around her.

“It’s gorgeous. Is it this pretty in the daytime?”

“Depends on the smog.” He grinned.

Inside the house she was less impressed. It was clean. But so small, so cramped! He sensed her feelings.

“Well, it’s not like Lake Shore Drive. Uncle John could have done better, no doubt,” he said.

“It’s—lovely,” she managed, with a smile.

“It’s just till we get a little ahead, honey,” he said quickly.

Beth fed the children and put them to bed with Charlie’s help. And then he pulled her down on their own bed, without even giving her time to take her clothes off. For fifteen minutes, in their quiet room, they talked intimately and Charlie stroked her and began to kiss her, sighing with relief and pleasure.

Suddenly Skipper yelled. Bellyache. Too much excitement on the plane. Beth jumped up in a spitting anger and Charlie had to calm the little boy as best he could.

Beth was surprised at herself. She was tired and she had had an overdose of children that day. And still she responded to Charlie with a sort of wondering happiness. She didn’t want anything to intrude on it or spoil it. Maybe this was the beginning of a new understanding between them, a better life, even a really happy one.

A half hour later Skipper woke again. Scared. New room, new bed, new house. And when Beth, nervous and impatient, finally got him down again, Polly woke up.

Beth’s temper broke, hard. “Damn them!” she cried. “Oh, damn them! They’ve practically ruined my life. They’re driving me nuts, Charlie, they’ll end up killing me. The one night we get back together after all these months—” she began to cry, choking on her self-pity and outrage—“those miserable kids have to spoil it.”

“Beth,” Charlie said, grasping her shoulders. His voice was stern and calm. “Nothing can spoil it, darling. Get a grip on yourself.”

Polly’s angry little voice rose over Charlie’s and Beth screamed, “One of these days I’ll croak her! I will! I will!”

And suddenly Charlie, who adored his children, got mad himself. “Beth, can’t you go for a whole hour without losing your temper at those kids!” he demanded. “What do you expect of them? Skipper isn’t even two years old. Polly’s a babe in arms. Good God, how do you want them to act? Like a pair of old ladies? Would that make you happy?”

“Now you’re angry!” she screamed.

He clasped his arms against his sides in an expression of exasperation. “You were in love with me five minutes ago,” he said.

Beth didn’t know quite what had gotten into her. She was tired, worn out from the trip and the emotions, fed up with the kids. She had wanted him, coming home in the car. Now all she wanted was a hot bath and sleep.

She walked out of the bedroom and slammed the door behind her. But Charlie swung it open at once and followed her, turning her roughly around at the door to the bathroom.

“What’s that little act supposed to mean?” he said.

She stared at him and the kids continued to chorus their sorrows in screechy little voices. Charlie’s big hands hurt her tender arms and his eyes and voice had gone flat.

“I won’t argue,” she said, her voice high and shaky. “I won’t argue with you. You don’t understand anything about me. You never have understood me!”

He looked into her flushed face and answered coolly, “You never have understood yourself, Beth. If you knew who you really were it wouldn’t be so hard for me to know you. Or anybody else.”

That infuriated her. She hated to be told that she didn’t know herself and it was one of the things Charlie always told her when he was mad at her. She hated it the worse because it was true.

“You lie!” she cried. “You bastard!”

Charlie pushed her back against the wall, so hard that her head snapped and hit the plaster with a stuffy thump. He kissed her. He was not very nice about it.

“If you think you’re going to make love to me, tonight, after the way you’ve just been acting—” she panted furiously at him, struggling to free herself— “if you think I’ve come two thousand miles just to let you rape me—”

“You shut up,” he said harshly, and kissed her again. He nearly crushed her mouth and she would have screamed again if she had been able. When he released her she slashed at him with her nails and he pulled her by her wrists back into the bedroom.

Beth tried all the old favored tricks of crossed women. She kicked, and flailed with her dangerous nails; she tried to bite him; she whacked him with a knife-heeled pump, thrilled to see a slightly bloody scratch bloom on his shoulder.

But Charlie smothered her with his big body. He just rolled on top of her and told her, “Shut up. You’re noisier than those poor kids you complain about all the time.” The sheer weight of him overwhelmed her. Struggle was futile, arguments were useless.

While he fumbled with her underthings she said, “You’re a brute. You bring me home to this miserable little cracker-box, you drag me all the way to California for this. This!” She tried to gesture at the four walls, to make him feel her disdain. “At least in Chicago I’m treated like a human being.”

He kissed her angrily.

“I am a human being, in case you didn’t know.”

He kissed her again, and his hands found her breasts.

“If you touch me I’ll be sick. I’ll throw up every goddamn thing I ate on that plane. Including the biscuits.”

But he touched her. He touched her all over, shivering all through his large frame and groaning. Beth began to sob with hurt and confusion and rebellion. And most dreadful of all, most humiliating, with desire. She wanted him. He was wonderful like this, the live weight of him on her yielding flesh, the thrust, the warmth, the sweat, the sweet moaning. When he took her like this, like a master claiming a right, she submitted, and she experienced relief. She did not know who she was, but for a little while he made her think she knew. He made her feel her womanhood.

And when he had forced her to surrender once, she gave in again without fighting. He kept her busy for a long time. If the kids kept up the noise their parents didn’t know it and didn’t care. Charlie wouldn’t let her out of his arms. He wanted her there where he could fill his nostrils with the scent of her, his arms with the smooth round feel of her. Four months is a damn long time for a husband in love with his wife to make love to a pillow.

It had not been quite like that between them since their college days and it was not like that again very often.

Chapter Three

THEY FELL INTO THE ROUTINE THEN WHICH BECAME SO DULL and empty to Beth over the next few years. At first she was too busy getting settled in her new home to be bored. She inspected the holly, the palms, the poppies, the bamboo that grew, rare and exotic, in her own backyard. She breathed in the mountains in back and the sparkling valley in front. But little by little she grew used to them. You can’t live with the marvelous every day and keep your marvel quotient very high.

Charlie and Cleve worked hard on the toys, and Charlie loved it. He liked keeping his own hours, being the boss, running the show. Almost imperceptibly he began to take on the lion’s share of the work and, with it, the lion’s share of the decisions. He was willing to spend nights in the office working out new plans or briefing new men. It made Beth cranky with him. And the crankier she got the more he stayed away. It was the start of a vicious circle.

“It must be my fault. I must bore you to death!” she cried. “No, Beth, you don’t bore me,” he said, climbing into his pajamas while she watched him from her place in the bed. “You scare me a little, but you don’t bore me.”

“I scare you! Ha!” She said it acidly, but only to cover her chagrin. She didn’t dare to ask exactly what he meant, and he didn’t bother to tell her. But her fits with the children, her depressions, her lack of interest in the love that should have sparked between them, had something to do with it.

Charlie reached the point where he couldn’t tell if Beth ever wanted him or not. She got him, because he didn’t have the strength or the patience to turn monk. But there was none of the old smoldering response that had used to thrill his senses and reassure him of her answering passion. She was quiet and she made the minimum gestures mechanically. As he had blurted unintentionally, it scared him. Dismayed, he had tried once or twice to talk to her about it. Not knowing how to be subtle, he simply exclaimed that something was wrong and she had damn well better tell him what it was before it got worse. But Beth had given him a smirk of half amusement and half contempt that had withered his pride and driven him to silence.

So things rolled along. The business was never quite good enough to get them a bigger house or the flashy sports car Beth wanted. Cleve was never quite drunk enough to botch his job. Beth didn’t have enough love and Charlie didn’t have enough insight. And that was their life.

For Beth it was dismal. She yearned for a diversion, an escape hatch, anything. Travel, a new car, an affair even. But all she had were her boisterous children, her irate husband, and bowling twice a week with Jean Purvis. Her mood was desperate.

Things took an odd turn finally, one night when Jean and Cleve invited Beth and Charlie to a birthday party. It was for Cleve’s sister, Vega Purvis. Beth remembered Vega very well. She had met her shortly after she arrived in California, and though she had never gotten to know Vega well, she was interested in her.

Vega was a model. She was a very tall girl, at least as tall as Beth herself, and excruciatingly thin. Throughout her twenties she had worked at modeling in Chicago and then suddenly came down deathly sick with tuberculosis, ulcers, and Beth had never known what else. Everything. It had meant the temporary finish to her working days and a long trip to the West Coast, where she went directly to the City of Hope for help. She was there for over two years.

Vega had sacrificed a lung to her tuberculosis, a part of her stomach to her ulcer, and perhaps more of herself to other plagues. And still she was stunningly beautiful. Still she smoked two or three packs of cigarettes a day—something that struck Beth as insane but rather wonderful, as if Vega had taken a bead on Death and spat in his eye. Nobody else would have gotten away with it. Vega brushed it off, laughing. “The first thing I asked for when I came out of the anesthetic,” she said, “was a cigarette. The doctor gave me one of his. Tasted marvelous.”

Vega had deep-set eyes, almost black, and fine handsome features, and she was witty and interesting. She was running her own model agency now on Pasadena’s fashionable South Lake Street—mostly teenage girls, with one or two older women who took the course for “self-improvement.” Or, perhaps, self-admiration.

Beth recalled the night she had first met Vega. They waited for her, Cleve and Jean and Beth and Charlie, in a small restaurant near her studio. Vega came late. It was necessary to her sense of well-being that she arrive late wherever she went. So Charlie and Beth and the Purvises waited for her in a small booth in the Everglades, where everything was chic and expensive.

Vega swept in at last, forty minutes late, wrapped in a red velvet cloak, and she was so striking that Beth had stared a little at her. She sat down and ordered a martini—double, dry, twist of lemon—before she greeted anybody.

She had a lovely face but it was, like the rest of her, painfully thin, with the fine bones sharply outlined. It soon became apparent why she didn’t put on weight. Vega rarely ate anything. She drank her dinner, though they had ordered her a steak. She seemed to depend on booze for most of her calories. Cleve persuaded her to take one bite, which she did, promising to finish the rest later—but of course she never did. Charlie and Cleve finally split the meat and ate it, but the rest was wasted.

Charlie was interested in her too. Beautiful women interest almost any man without making much of an effort.

“What do you do here, Vega?” he asked her. “Cleve said something about modeling.”

“I teach modeling,” she said, accepting a fourth drink daintily from the waiter. “Women are my business. Men are my pleasure,” she added, smiling languidly.

Charlie smiled back, unaware of the silly look on his face. Beth saw it, but it didn’t alarm her. It struck her funny, and before she had time to think about it, she was laughing at him. And suddenly the fun and flavor went out of the game for him, and he turned his attention to his meal. Beth saw his embarrassment and rebuked herself.

I should have been quiet, damn it, she thought. I should have let him have his fling. Such an innocent little fling. What’s wrong with me? But it was too late. Charlie was carefully casual with Vega the rest of the evening. It didn’t console him much, when he got home that night, to check his muscles in front of the mirror or stretch to his full six feet two. He was baffled and shamed by his wife, who laughed at even his normal masculine reactions. He was almost defeated by his inability to make Beth’s life mean something. On Vega’s birthday night they waited, as before, at the Everglades for her entrance, drinking whiskey and waters, and talking. Beth felt warm and relaxed after the first two drinks and she squeezed Charlie’s arm. It caused him some concern, instead of reassuring him, because it was unexpected.

“Good whiskey?” he asked, nodding at her glass. That must be the source of her pleasant mood.

“The best,” she said and smiled. “Why aren’t you nice like this all the time?” she teased clumsily.

“I’m only nice when you’re a little tight,” he said. “The rest of the time I’m a damn bore.”

It was so short and sad and true that it almost knocked the breath out of her. She looked at her lap, despising herself for the moment, feeling the tears collect in the front of her eyes. When she had to reach for a piece of tissue to stem the flood he murmured, “I’m sorry. God, don’t do that in here.” He had a masculine horror of scenes, especially in front of Cleve and Jean. Jean had noticed the little exchange between them and her smile—her permanent smile—wavered, but Cleve was talking to her and didn’t see.

“Come on, honey, this is a birthday party,” Charlie whispered urgently in Beth’s ear, exasperated and helpless like all men before a woman’s public tears.

Beth pulled herself together. She would save her bad feeling for later. Now she wanted to enjoy herself, to let the liquor take over, and the muted lights and the piped music. She wanted to forget her kids, forget she was married. Charlie lighted a cigarette for her.