Полная версия

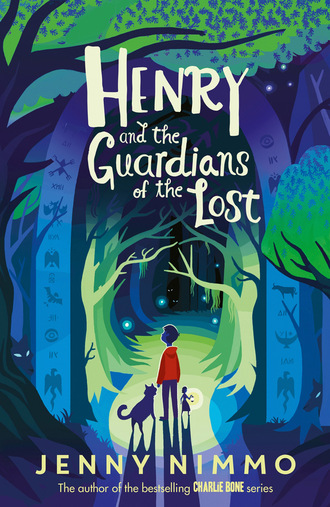

Henry and the Guardians of the Lost

‘She disappeared,’ said Mrs Reed in a matter-of-fact way.

‘Disappeared?’ Henry’s voice was tight and dry. ‘Did you phone the police?’

There was a troubling silence while Mrs Reed took off her apron and sat at the table. ‘There are no police here, dear,’ she said, patting Henry’s hand.

‘No police,’ Henry croaked. ‘None at all? Not even one?’

‘We have the mayor and his councillors,’ Mrs Reed told him in a firm voice. ‘They uphold the law. And then there are the henchmen, of course. Even they couldn’t find the girl.’

‘Oh.’ Henry felt weighed down by all this unwelcome news. The faces round the table were friendly enough, and the noise of chortling toddlers and boiling potatoes, and the sunshine outside the window should have made him feel cheerful, but he couldn’t rid himself of the thought that if someone else had been left in Martha’s Cafe, and then disappeared, he might disappear too.

Mrs Reed suggested that the children should go into the garden until lunchtime. Henry refused. So Peter took him up to his bedroom. Enkidu followed. He was keen on bedrooms.

There was a spare bed in Peter’s room, already made up for his friend, Bill, who often slept over. ‘So we’re always prepared, you see,’ said Peter.

Enkidu jumped on the bed, curled up and closed his eyes.

Lunch wasn’t tasty but it was very filling. In the afternoon Peter and Penny persuaded Henry to walk between them a little way up the road. Timeless looked like any other small town. A few of the neighbours waved, and a friend cycling past cried, ‘Hi, Peter!’

Henry noticed that there were very few cars, and several people were pale and dishevelled. Peter saw Henry staring at a woman whose face was so white she looked like a ghost. She appeared to be exhausted and could barely put one foot in front of the other.

‘She tried to get through,’ Peter said with a grin.

‘Through?’ said Henry. ‘Through what?’

‘You’ll find out.’ Penny gave a giggle. ‘You’d think they’d know better by now.’

Henry felt very uneasy. He wanted to ask more, but guessed that no one would tell him anything – yet. He’d have to find out for himself.

At the end of the road a sharp rise led to a grand house standing behind ornate iron railings. It was four storeys high, with a steep slate roof and many sparkling windows. Shiny brass studs decorated the tall front door, and there were two door knockers. One a plain ring, the other a large hand.

‘The mayor’s house,’ Polly told Henry.

As she spoke the door opened and two men walked out. They wore midnight-blue suits, the jackets covered in gleaming insignia and the breeches tucked into tall polished boots. Each man carried an iron club and wore a steel helmet.

‘Henchmen,’ Peter said, almost reverently. ‘They keep the law very efficiently.’

I bet they do, thought Henry, observing the long, thick clubs.

The children turned and walked back to Number Five. A cold wind had sprung up and Henry put his hands into his pockets to keep them warm. His fingers curled around a scrap of paper.

At first he thought it was an old note from school that he’d forgotten to give Pearl. But when he opened the folded paper he saw that the note was from Pearl. She had obviously been in a hurry; the writing was slanting and spidery. It said:

Forgive me, Henry. I did it for the best. I’ve no time to explain. I have to be out within the hour. Go round to the trees behind the cafe. Keep yourself hidden and wait for Mr Lazlo. Ask him where the white bird flies. He must reply, ‘In the Little House.’ Anything else and he’s the wrong person. Tell no one!

I’ll think of you every day.

Your loving aunt,

Pearl x

Henry pushed the note back into his pocket and kept on walking. Polly and Peter paid no attention. They probably thought he’d found an old message from a friend.

They reached the gate at Number Five and, all at once, Henry felt uncomfortably shaky. He stood by the gate while the others walked up to the front door. I’m in the wrong place, he thought. Tell no one, the note said. So how could he explain it if he decided to return to the hiding place behind the cafe?

‘You OK, Henry?’ Peter asked.

Henry nodded. He smiled uncertainly.

‘Maybe it’s jet lag?’ Penny offered.

‘I didn’t fly here,’ Henry mumbled. Pearl wasn’t coming back and he’d missed the person he was supposed to meet. He followed the Reeds into the house. Where else could he go?

Mr Reed appeared at suppertime. He had a wide face and thinning black hair. His cheeks were rosy and he smiled easily. He shook Henry’s hand and patted his shoulder, saying, ‘Things will be all right, Henry. We’ll make sure of that.’

How? Henry wondered.

‘Should we let the mayor know?’ Mrs Reed asked her husband.

Mr Reed shook his head. ‘Not yet.’ He darted a look at Henry and smiled. ‘We haven’t heard Henry’s story.’

Henry had nothing more to tell. He certainly wasn’t going to reveal his secret to these strangers, or mention Pearl’s note.

They sat round the kitchen table, eating bacon, beans and eggs. Enkidu was given some bacon fat. The smallest baby was in bed, the toddlers ate noisily. No one else said much. Henry kept thinking of the note in his anorak pocket.

‘So are you going to tell us why your aunt brought you here?’ Mr Reed asked Henry halfway through the meal.

Henry hesitated. He had to say something, and he wouldn’t be giving anything away by describing his journey. ‘She got a letter, my aunt. I don’t know what it said. She never told me. She was in an awful hurry. We drove all day and then went through an arch carved with bones and stuff. The next moment we were in total darkness, and the car was floating, then suddenly it was morning.’ He took a deep breath. ‘We went to Martha’s Cafe, and when I wasn’t looking my aunt left.’

Mr Reed nodded. He didn’t seem at all surprised. ‘And your aunt gave you no instructions, nothing to indicate where you should go, what you were to do?’

Henry thought of the note. Tell no one. He shook his head.

Peter gave him an odd look. It made Henry feel uncomfortable. He couldn’t stop his cheeks from reddening. He wondered if the Reeds noticed. He felt very hot.

‘Just like the other one,’ Penny said thoughtfully. ‘She disappeared in the night, after curfew.’

‘Curfew?’ Henry said. ‘Curfews are for prisons and . . . and wars, not normal towns.’

The Reeds all laughed. What was so funny? No one explained.

After supper, Mr and Mrs Reed took the toddlers upstairs for their bath. Penny did her homework at one end of the kitchen table, while Henry taught Peter how to play Battleships at the other end. The room was lit by gas lamps that popped and fizzed from the wall. Henry found that he could hardly keep his eyes open and remembered that he and Pearl had driven through the night. A large old clock hung above the stove. It was stained and rusty and, like the clock in Martha’s Cafe, it had stopped at half past twelve. He asked Peter if he knew the time.

‘We won’t know for sure until the town crier comes round,’ Peter replied casually.

‘Don’t any of your clocks work? Don’t you have a watch?’ Henry asked anxiously.

‘Mm, no,’ said Peter, concentrating on his next move.

Henry felt a bit light-headed. ‘I think I’d like to go to bed,’ he said.

‘Good idea.’ Peter put down his pencil. ‘I want to finish my book before curfew.’

That word again. Henry asked, ‘What happens at curfew?’

‘Of course, you don’t have curfew, do you?’ Peter said in a patronising voice.

‘I have bedtime,’ said Henry. ‘At least I used to.’

‘Ah, well, the town crier comes round ringing his bell and telling us it’s ten o’clock. Everyone has to be indoors, and all the lamps and candles out.’ Peter said this as if it was the most normal thing in the world.

‘Even the street lights?’

‘The gas lights? Of course. And then the henchmen come round with a lantern, checking for curfew breakers.’

‘And if anyone breaks the curfew? What then?’

‘Don’t ask,’ said Peter. An unsatisfactory answer.

They were given candles in brass saucers to take to bed.

‘I expect you have e-l-e-c-t-r-i-c-i-t-y at home,’ said Peter, enunciating jokingly.

Puzzled, Henry said, ‘Most people do.’

Peter chuckled. ‘Not us. We do have a telephone, though. Just us and a few others. The mayor has a generator.’

Henry was glad to see that Enkidu hadn’t moved from the bed. The big cat was obviously making up for his undignified journey. When Henry got into bed he pushed his feet under Enkidu’s heavy body. It was comforting to feel his friend so close.

‘Don’t think I’ll read tonight,’ said Peter, blowing out his candle.

Henry did the same, but he lay awake, staring into the dark. Was he safe in this house? And if he got back to the cafe, would Mr Lazlo be there? He doubted it. He was drifting off to sleep when he heard a bell ringing outside the house. A voice called, ‘Ten o’clock and all’s well.’ Soon after this, the rhythmic sound of marching boots grew louder and louder. Tired as he was, curiosity drove Henry to the window. He looked down on a column of men, their helmets glinting in the fitful light of the moon. Henchmen.

Later, much later, Henry’s eyes opened again. There wasn’t a sound anywhere. But he was suddenly wide awake. He went to the window.

The moon was higher and brighter now. Peering through a gap in the curtains, Henry looked down at the road. A black horse stood by the garden gate. Its rider, a cloaked figure in a large beret, was looking up at Henry’s window. The man had a thick black beard and one gloved hand covered his mouth, as though he were puzzled or uncertain. In spite of the man’s forbidding appearance, Henry had to restrain a sudden urge to call out to him.

The man turned his head and looked up the road. The next minute he and the horse were gone. If it hadn’t been for the fading clatter of hooves, Henry might have believed that horse and rider had never existed.

And then came another sound. The heavy tread of approaching henchmen.

Henry slept deeply. When he woke up Peter had gone. Henry crept downstairs, wondering what time it was. The sun was high. Perhaps it was lunchtime. There was no sign of Enkidu.

The kitchen was deserted but breakfast hadn’t been cleared away. The table was strewn with boxes of cereal, jams, butter and a rack of toast.

Mrs Reed popped her head round the door and said, ‘Help yourself, Henry. Peter and Penny have gone to school.’

‘Have you seen my cat?’ asked Henry.

‘Not a whisker,’ said Mrs Reed. It was difficult to tell if she was joking.

After a large bowl of cereal and several pieces of toast, Henry was just wondering what to drink when Mrs Reed looked in again and asked, ‘How old are you, Henry? The headmaster will want to know.’

Henry reached for the orange juice. ‘Why?’ he said. ‘Am I going to school?’

‘Just a thought.’ Mrs Reed gave him her cool smile. ‘We have to find something for you to do, don’t we, until . . .?’ She seemed unable to finish her sentence.

Until what? Henry wondered. How long am I going to be here?

‘Nine?’ asked Mrs Reed impatiently. ‘Ten? Have you forgotten how old you are?’

Henry couldn’t see the point of lying. His brain was older than a ten-year-old’s. She would think he was small for his age. Nothing more. ‘Twelve,’ he said quickly.

‘Ah.’ Mrs Reed retreated.

After breakfast Henry wandered into the hall. What was he to do with himself ? The Reeds didn’t appear to own a television set or a radio, or even an electronic game. He was about to mount the stairs when Mrs Reed came out of a bedroom. ‘I’m sure you’ll find a book to read,’ she said. ‘I’ll ring the headmaster in a minute. Don’t leave the house, will you?’

‘I want to look for my cat,’ said Henry.

‘Don’t leave the house,’ Mrs Reed said harshly. ‘The cat will come back.’

Henry went into the sitting room. The shelves were full of rather dull-looking books. Henry pulled out a heavy volume entitled, Sailing Ships of the World. Some of the ships popped up when the book was laid flat on the table. He was admiring a sixteenth-century galleon when Mrs Reed made her phone call from the hall. There was something quiet and sly in her tone. Henry could only make out the occasional word. He assumed she felt awkward explaining his small size, and didn’t want him to overhear.

The phone call ended and Mrs Reed went back upstairs to where the baby was screaming.

For several minutes Henry continued to admire the Tudor galleon, observing the construction of the sails and the multitude of ropes and knots. A sudden tap on the window made him look round. Enkidu was outside, staring in at him from the sill.

Henry jumped up. ‘Enkidu!’ he mouthed. He walked slowly and stealthily into the hall, then crept to the back door, opened it quietly, turned and closed it. The latch clicked but the sound was drowned by the loud shouting of the baby.

As soon as Henry tried to grab Enkidu, the big cat leapt off the sill and bounded across the lawn.

‘Enkidu!’ Henry whispered as he gave chase.

Enkidu jumped over the gate. Henry opened it and ran through. The big cat waited while Henry closed the gate behind him. He found himself in a narrow, muddy lane. Enkidu immediately took off again, but at a more sedate pace. Henry trotted after him.

They were passing a patch of waste-ground between Number Five and Number Four when Henry heard the heavy tramp of iron-studded boots. He stopped and glanced up at the road. The footsteps ceased. Curious to know where the henchmen had stopped, Henry crept through the long grass, dodging behind small bushes and leafless trees. Enkidu kept close to his heels.

At last Henry had a view of the gate to Number Five. Two henchmen stood before it, their faces concealed by their helmets. They were consulting a notebook. The man holding the notebook nodded and opened the gate. They marched up to the front door, and Henry heard the loud rat-tat of the door knocker. He caught the sound of a door opening, and a murmur of voices. The door closed.

The next moment Henry was startled to hear his name being called. All over the house. He saw the bedroom window open, and Mrs Reed lean out, shouting his name.

With sudden and chilling certainty Henry knew that Mrs Reed had not phoned the headmaster. She had called the henchmen. Why? Were they connected to the villains his aunt was so worried about? Was there no safety anywhere?

He couldn’t return to Number Five. Ever.

‘It’s just you and me now, Enkidu,’ Henry said quietly.

Henry knew all about fear. When the shocking change to his life had occurred he had been so frightened he thought he would never recover. But he did, thanks to his cousin. Charlie had been crossing the great hall when Henry had arrived from the past, breathless, shocked and very scared. Charlie had hidden Henry. He had rescued and protected him, and then become his greatest friend. Henry wished Charlie was beside him now.

Mrs Reed was still calling Henry’s name as he crept back to the lane. Once there, Enkidu took off again. This time the big cat sped away so fast Henry almost lost sight of him. The lane twisted and turned and Henry couldn’t keep the flying ball of fur in sight. But he dared not call out. He came to a fork in the lane. On the left it carried on behind the houses, on the right a narrow track led into a dark wood.

Henry peered into the wood. He could see nothing but giant trees, twisted moss-covered roots and fallen branches wrapped in ivy. Enkidu sat on the track, just inside the wood.

‘Enkidu, are you sure about this?’ asked Henry. He couldn’t go back to the cafe. Henchmen might be lurking there.

The big cat turned and began to bound up the track. This time Henry didn’t give chase. Wherever the track led, Enkidu obviously wanted him to follow. Henry paced slowly between the trees. If only he had found his aunt’s note sooner. She must have written it when he was outside feeding Enkidu. He remembered she had straightened his anorak when she stood up to leave. Why couldn’t she have told him what would happen? He wouldn’t have protested. But then again, perhaps he would have done.

‘Good day!’ The voice was a shrill, strangled sound.

There was no one on the track ahead of him, or behind. ‘Hullo!’ said Henry.

‘Toast and jam!’ The sound floated in the air.

Henry looked up. A ghostly white shape dipped and hovered through the upper branches. He ran beneath it, his eyes never leaving the flying shape. The next moment he almost fell over Enkidu, who was also gazing at the white thing.

‘A bird!’ Henry declared, as the ghost came to rest on a branch above them.

A white bird. ‘Ask where the white bird flies,’ his aunt had told him.

‘A thousand times good-night,’ said the bird.

‘A cockatoo!’ Henry glanced at Enkidu. He seemed mesmerised by the bird.

‘You were following it,’ said Henry.

The cockatoo took off and they followed. Henry noticed that the trees around them were larger and darker. This was no wood. It was a forest. An ancient forest where small, unseen creatures moved through the shadows. He could hear a rustling, pattering, scuffling and, sometimes, a light flapping of wings.

A forest without end, thought Henry. He was in a foreign country, a timeless place. On they went, on and on into the darkness.

‘You and me, and a cockatoo,’ Henry told Enkidu and, in spite of their tricky situation, he smiled to himself.

At that moment he would have liked to rest on a welcoming pile of leaves, but the trees had begun to thin a little, and in the distance Henry could see tall wrought-iron gates. Beyond the gates there was a grey stone building with many steeply angled roofs and even a tower.

‘Where have you brought me?’ Henry muttered. Enkidu ran to the gates.

There was nothing welcoming about the old neglected-looking house but, for some reason, Henry felt drawn to it. He took a few paces towards the ornate rusted gates. A bell pull hung from a pillar on one side, its iron handle encrusted with lichen.

Henry went right up to the gates. He saw that part of the pattern at the top was formed from letters. There was a T, an L and an H. The other letters were rusted and misshapen but when Henry screwed up his eyes they became clearer. He made out a word, then another and another. An unmistakable name: ‘The Littles’ House’. And there was the white bird, perched on the porch roof.

Was this the place Pearl had meant him to come to? It looked deserted. What was he supposed to do now?

Before he could decide an ancient front door began to open. Even from the gate Henry could see the scratches and deep scars in the wood. He imagined soldiers kicking and battering the door in some long-ago battle.

There was a creaking and a shuddering, then a white-haired man appeared in the entrance. Henry found that he couldn’t move. The man wore a white shirt, a long leather waistcoat and green velvet knee-breeches. He began to approach Henry along a mossy, paved walk. On either side thistles and tangled briars reached to the man’s waist. He arrived at the gate and stared at Henry through the curling iron-work. He was short and wide and his face had a weathered tan. His eyes were a curious yellow, his lashes long and white.

‘Spy or rover?’ asked the man.

Henry stood his ground. ‘If I was a spy I wouldn’t tell you, would I?’

‘Suit yourself.’ The man turned away.

‘Wait! Please!’ begged Henry. ‘I think my aunt wanted me to come here. I don’t know why, but she wrote down the name. Look!’ He held Pearl’s note up to the gate.

‘She’s left off an s, and an apostrophe,’ said the man.

‘I can see that, but she was in a hurry,’ said Henry.

‘You were supposed to wait for Mr Lazlo,’ said the man. ‘He was detained for a time – a problem with the mayor.’

‘I didn’t find my aunt’s note straight away, and then these children, the Reeds, said I should come home with them.’

‘Dratted kids,’ grunted the man. ‘They did that to Flora, but we managed to get her out.’ He reached under his waistcoat and unhitched a ring of heavy keys from his belt. Choosing the largest he pushed it into a lock in the centre of the gates and pulled one open. ‘Come on, then,’ he said to Henry. ‘My name’s Herbert. I’m porter, handy-man, jack-of-all-trades and more.’ He winked.

‘I’m Henry, and . . .’ Henry looked round for Enkidu but the black and white cat had leapt in from of him. The cockatoo flew into the open doorway calling, ‘A plague on both your houses,’ and Enkidu bounded after it.

‘We can’t have cats in here,’ said Herbert. ‘You’ll have to get it out.’

Henry had no intention of getting Enkidu out of the house. If he was going in, then so was his cat. He followed Herbert up the path. When he reached the ancient, scarred door, he had a moment’s doubt. But where else could he go?

‘Get a move on.’ Herbert spoke from the shadows beyond the door. ‘You’re letting the outside in.’

Nervously clenching his fists, Henry stepped over the threshold. He had the oddest sensation of moving backwards, not forwards. He shook his head, and hunched his shoulders as Herbert closed the door behind him. The air was filled with whispers.

Facing Henry, on the other side of a musty-smelling hallway, was a wide wooden staircase. It rose to a landing where a large gilt-framed mirror reflected nothing but dust. Henry’s legs felt all at sea as the flagstones beneath his feet dipped into hollows and then rose unexpectedly.

A shaft of light brightened the hall as Herbert opened a door and proudly announced, ‘The kitchen.’

Henry thought, It’s just a kitchen. But as he stepped into the room he realised that it was not just a kitchen. It could better be described as an experience. The walls rose up and up until they reached a domed glass ceiling. The huge skylight was made of hundreds of topaz-coloured panes, giving the whole place the look of an old-fashioned photograph.

Below the ceiling two great oak beams ran the length of the room. They were hung with copper saucepans, cauldrons, bowls, ladles and other utensils the like of which Henry had never come across. They were all so far out of reach he wondered if anyone ever used them. And then he became aware of a stepladder, the tallest he had ever seen, and almost at the top, a very, very tiny woman.

‘Hullo!’ the tiny person squeaked. ‘You’re late.’

‘I know,’ said Henry.

‘Better late than never, eh?’ said Herbert. ‘Henry, meet Twig.’

‘Are you hungry?’ asked Twig.

‘A bit,’ Henry admitted.

Twig then did the most extraordinary thing. She leapt from the ladder, on to the top of a vast dresser. Every shelf was crammed with cracked and stained crockery, all piled higgledy-piggledy; plates balanced on bowls, cups teetering on one another. How it all stayed put was a mystery.

Bending over, Twig selected a large plate from the top shelf. Tucking this under one arm she bounced back on to the ladder, skimmed halfway down, and jumped on to the impossibly long table. It was only then that Henry saw the girl. She sat at the very end of the table. Behind her a window as wide and as tall as four doors rose above a giant stone sink. The girl’s hair was as red as a flame. She was reading a book and took no notice of Henry whatsoever.