Полная версия

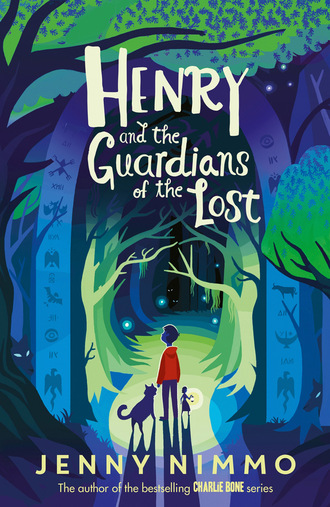

Henry and the Guardians of the Lost

First published in paperback in Great Britain 2016

by Egmont UK Limited

The Yellow Building, 1 Nicholas Road, London W11 4AN

Text copyright © 2016 Jenny Nimmo

Cover illustration by George Ermos

The moral rights of the author and illustrator have been asserted

First e-book edition 2016

ISBN 978 1 4052 8087 7

Ebook ISBN 978 1 7803 1740 3

www.egmont.co.uk

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Stay safe online. Any website addresses listed in this book are correct at the time of going to print. However, Egmont is not responsible for content hosted by third parties. Please be aware that online content can be subject to change and websites can contain content that is unsuitable for children. We advise that all children are supervised when using the internet.

For Max, with love.

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

The Yellow Letter

Timeless

Henchmen

The House in the Forest

Into the Tower

The Mayor and His Monster

Hiding in the Attic

A Cry in the Night

Ankaret and the Bomb

The Guardians

The Shaidi Workroom

Talk of Goblins

The Night Forest

The Goydrok

Miss Notamoth’s Surprise

The Day of the Pan Shining

Lucy’s Whisperers

Trapped

The Tempest

The Wizard

Back series promotional page

The yellow letter arrived on a Saturday, otherwise Henry would have been at school. The envelope was such a bright, sunny colour, no one would have believed that it contained a bombshell

There had been a storm in the night and the postman was late. Henry went out to see if the wild ocean had flooded the road. He knew he shouldn’t stand so close to the edge of the cliff, but he had survived so many dark and dangerous events, he had decided that nothing could finish him off. That was before he knew the contents of the yellow envelope.

Henry lived with his aunt, Pearl, and a black and white cat called Enkidu. Pearl wasn’t his real aunt, she was more of a minder, but she was distantly related to Henry, and also his cousin, Charlie. Henry’s parents had died long ago, nearly a hundred years in his father’s case. How could that be, you might ask, if Henry was only twelve?

That was his secret.

Henry’s life had changed in an instant, almost a century ago. He had been alone in the great hall of his uncle’s gloomy house when a large and beautiful marble had come rolling towards him. Unaware of the danger, Henry had picked it up and looked into it. He had been thrust into the future, and had lived in the present for almost two years, but in all that time he hadn’t grown. Not one inch.

Henry’s home was a small white-washed house perched halfway up a rugged cliff. For obvious reasons the house was called Ocean View. It was a place of safety for a boy whose past was almost too incredible to be believed.

Frank, the postman, arrived at last. He was a wiry, cheerful person with a wide smile and large, pink ears. He never complained about the steep lane that led up to the house nor the road below that was frequently puddled with sea water.

Henry met Frank at the front door. ‘Hullo, Frank. Have you had a bad time?’ Henry looked up at the rain-filled clouds.

‘Not so bad.’ Frank placed a bundle of mail in Henry’s hands.

The yellow letter was on top.

‘Interesting!’ Frank tapped the stamp in the corner. ‘Diplodocus, is it?’

‘Iguanodon,’ said Henry.

‘I’ll learn them one day.’ Frank grinned and got back into his van. ‘Give my regards to Auntie Pearl!’ he called as he sped off.

Henry regarded the yellow envelope. The name and address had been written in a large sloping hand. There was no mistaking Aunt Treasure’s round dots and sweeping tails. He took the mail into the kitchen where his aunt was making a chocolate cake.

Pearl was a small, round woman with dark, greying hair and permanently rosy cheeks. Henry placed the letters as close to the mixing bowl as he dared. He waited, hopefully, for Pearl to pick up the yellow envelope. She glanced at it and smiled. ‘Ah, from my sister.’

But the letter wasn’t opened until the chocolate cake was in the oven and Pearl’s hands were clean. Henry tried not to appear nosey, but he was keen to know what Treasure had to say. He sensed a secret, something too important to be said on the phone.

Pearl took ages to read the letter. The more she read, the more she frowned. It seemed that she couldn’t quite comprehend what her sister had written. And then she opened her eyes, very wide, and dropped the letter. Clasping her face in both hands, she said breathily, ‘Henry, go and pack your bag.’

‘What?’ Henry couldn’t believe Pearl’s instruction.

‘Now!’ she commanded. ‘Now, Henry. Not a moment to lose.’

‘But . . .’

‘Didn’t you hear what I said?’ Agitation made her words sound like a kind of scream.

‘You said pack a bag. But why?’

‘I’ll explain later.’ Pearl tore off her apron and ran to the kitchen door. ‘Come on, Henry. This is no time to dream.’

‘I’m not dreaming,’ Henry mumbled as he followed Pearl upstairs. ‘Or maybe I am, because I’m not sure that this is really happening. Charlie was coming today.’

‘Not now,’ said Pearl.

‘But we’d made plans. I’ve been thinking about them all week. Charlie is the only –’

‘You can see your cousin when . . .’ Pearl hesitated. ‘When all this is over.’

‘All what? Charlie’s my best friend, and I only see him at weekends.’

Pearl ignored him. ‘Pack everything you might need: pyjamas, wash-bag, clean underwear . . .’ She reeled off a list. Henry wondered how he was going to fit it all in.

Enkidu, Henry’s cat, was asleep on his bed.

‘We’re going away,’ Henry told his large, exceptionally fluffy friend. ‘So who’s going to look after you?’

Enkidu didn’t appear to be concerned. He was snoring.

Henry began to throw things into his bag, while Pearl shouted from her room. ‘Hurry, hurry, hurry!’ And then she called, ‘Henry, take something you love.’

Henry looked at Enkidu. ‘OK,’ he called back.

Throwing stuff out of his bag, he picked up Enkidu and put him in the bag. Enkidu didn’t mind. He didn’t even wake up. But he stopped snoring. If he hadn’t, things might have turned out very differently.

Henry zipped up the bag, leaving a tiny gap at the end to give the cat some air.

Pearl was already thumping down the stairs. Henry ran after her. He grabbed his anorak from the hallstand as Pearl opened the front door. ‘Come on, come on!’ she said.

‘Can’t you tell me where we’re going?’ Henry complained.

‘Somewhere safe,’ Pearl murmured. ‘It’s complicated.’

But I was safe here, wasn’t I? Henry thought.

Just in time, Pearl remembered to turn off the oven. She didn’t bother to remove the cake. When they were both outside Pearl locked the front door. Henry saw that her hands were shaking. A bad sign; Henry thought Pearl was a risky driver at the best of times. He waited while she backed the car out of the lean-to beside the house.

‘Hop in!’ called Pearl when she had manoeuvred on to the lane.

Henry put his bag carefully on to the back seat, then jumped in beside his aunt. He noticed that Pearl had only brought a handbag. There was no sign of anything for her overnight things.

‘Aren’t you –?’ Henry began.

‘Hold tight,’ said Pearl.

They swooped down the muddy lane and bounced on to the wet road. After ten minutes they turned off on to a narrow track. Henry had never gone this way before. Half an hour later they emerged on to a busy main road. On and on they went, through villages and small towns, over bleak brown moors and narrow bridges, through tunnels and around forests. The light began to fade and evening mists drifted up from the damp fields.

‘You said you would tell me why we’re doing this.’ Henry’s head felt heavy and he could hardly keep his eyes open.

Pearl took a breath. ‘People were coming.’ Her voice became deep and grave. ‘Someone talked about you, Henry. We don’t know who, it could have been quite accidental. But anyway, these . . . these beasts got wind of you, who you are and how you haven’t grown. And they would have taken you, Henry, for . . .’ her hands tensed on the wheel, ‘who knows what. But certainly I couldn’t have stopped them.’

Henry shivered. He was suddenly wide awake. ‘The yellow letter,’ he said. ‘It was a warning.’

‘Yes, from Treasure. She tried to ring but our phone was out of order, and we don’t get a mobile signal in our faraway part of the world.’

‘But why, Auntie Pearl? Why were they so determined to take me?’

She took a moment to reply, and then she said quietly, ‘They believe that you, and others like you, hold the key to obtaining the greatest prize on earth.’

‘And what’s that?’ asked Henry, somehow dreading the answer.

‘I think you can guess,’ his aunt said gravely. ‘The secret of eternal youth.’

‘Because I haven’t grown,’ Henry whispered.

They drove in silence for a while, and his mind raced so fast he began to feel dizzy. A loud noise from his stomach distracted him. He thought of the chocolate cake left in the oven. ‘Did you bring sandwiches?’ he asked, without much hope. ‘Or biscuits?’

Pearl shook her head. ‘I’m sorry, Henry.’

Henry tried not to think about food, but he couldn’t help thinking of the chocolate cake, with loads of chocolate icing on the top. He could even taste it.

They drove through a dark, dense pine forest, emerging, at last, on to a wide road where lights twinkled in the distance.

‘There’ll be somewhere to eat,’ Pearl said cheerfully.

And there was. Halfway down the high street of a friendly-looking village they found a small, bright cafe with steamy windows and red checked tablecloths.

Henry tried to forget the people that were coming to get him, while he concentrated on his food. He had almost finished his large plate of sausages, chips and beans when he suddenly remembered his cat.

‘Enkidu!’ he cried, dropping his fork.

‘He’ll be fine,’ said Pearl, in a matter-of-fact voice.

‘He’s in the car,’ said Henry, ‘in my bag.’

‘What?’ Pearl scrunched up her eyes. ‘How could you be so stupid?’

‘You told me to bring something I loved,’ said Henry defiantly.

Pearl gave a loud sigh of exasperation. She put her keys on the table. ‘You’d better let him out. He’ll want to go for a pee.’

It sounded as if Pearl hoped Enkidu would go off and not return. Henry grabbed his remaining sausage and dashed outside. Enkidu ate the sausage gratefully, had a pee in a muddy verge, covered it with leaves and happily jumped back into the car.

Henry was about to run back into the cafe when Pearl came out of the door. ‘In the car, Henry,’ she said. ‘We must keep going.’

Henry hadn’t finished all his chips, but Pearl looked so stern, he didn’t like to mention it.

They drove through the darkness, their headlights shining on long, winter grass and high, wild hedges. On and on.

‘How d’you know where to go, Auntie Pearl?’ Henry’s voice sounded small and fearful.

‘A map in my head,’ she said. ‘My sister put it there.’ And there was the ghost of a smile in her voice. ‘We’re looking for an arch with carvings on it, birds and beasts and flowers and things.’

Henry became aware of a wall beside them. Not the usual kind of wall, but a screen of trees, laced with stone. A wall that vanished now and then, like a memory, a dream, a wall that could never be touched, a wall that would never let you through. And, all at once, there was the arch that would allow them into a place that had appeared to be forbidden.

‘Not birds and beasts,’ Henry whispered. For the carvings in the pale stone pillars of the arch were not birds, they were the bones of sad, fragile creatures that perhaps no longer existed.

‘It’s nearly midnight,’ said Pearl. ‘We’re just in time.’

‘Midnight already?’ Henry sat up very straight in his seat. Pearl accelerated a little, as though she wanted to get through the arch as soon as possible. They passed under the big, ghostly stones and emerged into total darkness.

The engine stopped. The headlights went out. Perhaps they were not in the car at all, for Henry couldn’t feel the rim of his seat, or his safety belt. He could hardly breathe. The darkness all about them was so dense and so black it seemed to smother them.

Enkidu growled.

Henry reached for Pearl’s hand. He could feel nothing.

‘It’ll be all right, Henry.’ Her voice came from a long way away.

Slowly the impenetrable darkness began to lighten. The smothering feeling lifted and Henry could hear the reassuring purr of the engine. They were moving again, and as they moved a peculiar thing happened. Ahead of them the sun began to rise; higher and higher, faster and faster. The night clouds melted away, leaving the sky a clear ice-blue.

‘There,’ said Pearl, pulling down her sunshield. ‘All is well.’

‘Is it?’ Henry was baffled by the sudden appearance of the sun. What had happened to the hours between midnight and sunrise? ‘You said there were birds on the arch. Those weren’t birds.’

‘Treasure’s writing is a little . . . untidy.’ Pearl gave an unconvincing chuckle.

They were travelling along a road that ran between rows of warehouses. Beyond them a vast forest stretched as far as the eye could see. The huge doors in every warehouse had been thrown wide open, as though in expectation of some giant delivery.

‘Weird,’ said Henry. ‘We seem so far from anywhere.’

‘The equinox,’ his aunt murmured.

‘The equinox?’ Henry inquired.

‘The sun tips over the horizon,’ she said, ‘and night is as long as day.’ It was the only explanation that she seemed prepared to give.

When they had passed the warehouses, a church spire came into view, and then a cluster of roofs. Pearl was driving dangerously fast, Henry thought. Perhaps she was trying to catch a mirage before it disappeared. But as they drew closer to the buildings, Henry could see that it was a mirage; they were about to enter a small town.

‘Timeless’ said a sign beside the road.

Henry could see nothing special about the place, except that the frost and sunlight made it look very bright.

‘There it is,’ cried Pearl. ‘I’m dying for a cup of tea.’

They stopped outside a cafe with a pink and orange awning. Above the awning, the words, ‘Martha’s Cafe’ had been painted in blue and orange, the top of each letter decorated with a pink cupcake. Behind the cafe, trees loomed – their naked branches festooned with ivy.

Henry was hungry again. Pearl ordered eggs on toast for them both, tea for herself and hot chocolate for Henry. Her mood had changed again. Her smile had gone. She ate quickly and when she had finished her breakfast, she stood up, saying, ‘I’m just going to tidy my hair.’ And then she came round the table and kissed Henry’s cheek.

It was the first time that Pearl had kissed him before going to the toilet. He hoped she wasn’t going to make a habit of it.

Henry finished his meal and drained his cup. Pearl was taking a long time. Her hair had looked perfectly tidy. After all she’d been inside a car all day, or was it all night? He noticed two children sitting at a table by the window: a boy and a girl, about his age. They wore purple-coloured sweaters and grey trousers. The girl had long brown hair, a small nose and a wide, serious face. They boy looked exactly the same, only his hair was short. They were both staring at him.

Henry returned their stare and then, feeling self-conscious looked down at his plate. Several minutes passed. What was Pearl doing? He didn’t like to go and look in the Ladies’ cloakroom.

The children were still staring at him. Henry felt uncomfortable. All at once the girl stood up and came over to his table.

‘Are you meeting someone here?’ she asked.

‘Er, no,’ said Henry.

‘Was that your gran who just went to the cloakroom?’

‘My aunt,’ said Henry.

‘Well . . .’ The girl swung from foot to foot. ‘I think she’s forgotten you.’

‘No, she hasn’t,’ said Henry indignantly. ‘She’s just taking a long time.’

The girl shook her head regretfully. ‘We just saw her get into a blue car that was parked outside.’

‘I expect she was fetching something she’d forgotten,’ said Henry, wondering why Pearl had gone out without telling him. He had his back to the entrance and couldn’t see the cloakroom door.

‘She drove away,’ said the girl.

Henry felt a bit sick. He chewed his lip. ‘She couldn’t have.’

The girl pulled out a chair and sat opposite him, then the boy came over and stood between them. He had a calm, confident expression. ‘She hasn’t come back,’ he said. ‘I’ve been watching.’

Henry was slightly annoyed. What business did these children have, watching him and his aunt? He felt his heart thumping and told himself he wasn’t worried.

‘D’you want to come home with us?’ asked the girl.

‘No,’ Henry said fiercely. ‘I’ll wait here. I know my aunt will come back.’

‘We’ll wait with you.’ The boy pulled a chair across from another table and sat down.

Henry could see now that the boy was older than the girl; he was also quite a bit taller. He obviously liked to take control of certain situations.

‘My name’s Peter,’ said the boy. ‘Peter Reed. And this is Penny.’ He nodded at the girl who gave Henry a weak smile.

Henry thought it would be churlish not to give them a bit more information about himself, so he told them his name and where he had come from. When he described the hurried drive through the night, Peter gave Penny a slightly furtive smile. Henry kept his secret to himself. In the friendly school at home, they were used to him and never pried. But now he was in unfamiliar territory and he knew he must be ‘on his guard’.

‘We always come here early on Sunday mornings,’ said Peter. ‘You get the best doughnuts.’

‘Want one?’ asked Penny.

Henry hesitated. Nothing wrong with a doughnut, he thought. ‘OK,’ he said. ‘Thanks.’

Peter went to the counter to buy three doughnuts. When he came back, Henry glanced at the clock on the wall. It had said half-past twelve when he and Pearl had come in. It still did. He looked at his watch: half-past twelve.

‘The clock’s stopped,’ Henry remarked. ‘So has my watch.’

‘No time here,’ said Penny. ‘Not in Timeless.’

‘No time like the present,’ Peter said with a grin.

‘Time flies,’ trilled Penny. ‘Time stands still.’

Henry had an urge to tell them both to shut up. He felt angry and confused.

‘You’d better come home with us,’ said Peter. ‘Our parents will help you.’

Henry didn’t like being bossed. ‘I think I should stay and wait for my aunt,’ he said, biting in to his doughnut.

‘Leave a note for your aunt with Martha,’ Penny suggested. ‘Tell her you’ve gone to Number Five, Ruby Drive. You can’t stay here all day.’

Henry could see that she had a point. The cafe was filling up and people were searching for spare tables. When the doughnuts were eaten, he went to the counter and left a note with the friendly woman called Martha. The note said:

Dear Auntie Pearl,

You didn’t come back, so I’ve gone to Number Five, Ruby Drive. I’ll wait for you there.

Love from Henry

When they stepped outside a large black and white cat came running up to them.

‘Enkidu!’ Henry knelt and flung his arms around the cat, burying his face in the long, soft fur. ‘Did Pearl throw you out?’

‘He was already out when the car left,’ said Peter. ‘I noticed him sitting behind the bins.’

‘Hiding,’ said Penny. ‘He wanted to stay.’

Henry gathered Enkidu into his arms. ‘Thank you! Thank you, Enkidu,’ he whispered in the cat’s hairy ear.

Number Five, Ruby Drive was only a few minutes away. It was a red brick, modern-looking house with a small front garden and a path paved with red and black tiles.

Peter unlocked the front door and Penny followed him into the house. Henry hesitated on the doorstep.

‘Come on,’ said the Reeds.

Henry carried Enkidu into Number Five. It seemed welcoming. There were red tiles on the floor and the wall was covered with framed photos of Peter and Penny holding silver cups, bronze medals and official-looking certificates. Henry had never won anything.

Peter and Penny led Henry past a red-carpeted staircase to a room at the back of the house.

‘Look, Mum,’ said Peter, opening the door with a bit of a flourish, ‘another one. Ta da!’ He shoved Henry into a room that seemed to be crammed with children; three small ones to be precise.

Two toddlers and a baby were playing on the floor. A woman with short brown hair and spectacles stood at the kitchen sink, peeling potatoes. She turned to Henry and said, ‘Ah! I see. What’s your name, dear?’ Her eyebrows were raised in an interested but not exactly friendly way.

Henry didn’t reply. He was wondering what they meant by ‘another one’.

‘His name is Henry Yewbeam,’ Peter told his mother.

‘Come in, dear, and have a cup of something,’ said Mrs Reed.

‘Tea,’ said Penny firmly. She filled a kettle and put it on the gas stove.

Peter pulled out a chair, saying, ‘Sit down, Henry. You’ll be OK. We’ll try to make sure of that.’

Try? thought Henry. He sat down and put Enkidu on his lap.

‘That’s a very fine animal,’ Mrs Reed remarked.

‘His name’s Enkidu,’ said Henry. ‘I hope you don’t mind cats.’

‘Not at all.’ Mrs Reed smiled. ‘Our old tabby died a month ago, and we’ve been looking for a replacement. Your cat can use Tibby’s cat-flap.’

Henry’s grip on Enkidu tightened. ‘What did you mean when you said you’d found another one?’ he asked Peter.

Penny put a cup of tea in front of Henry. ‘There was a girl,’ she explained. ‘Just like you, left in Martha’s cafe, all alone, no mum or dad, just a suitcase. Mum brought her home, didn’t you, Mum?’

Henry stared at Mrs Reed. ‘What happened to her?’