полная версия

полная версияThe Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 10, No. 275, September 29, 1827

Various

The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction / Volume 10, No. 275, September 29, 1827

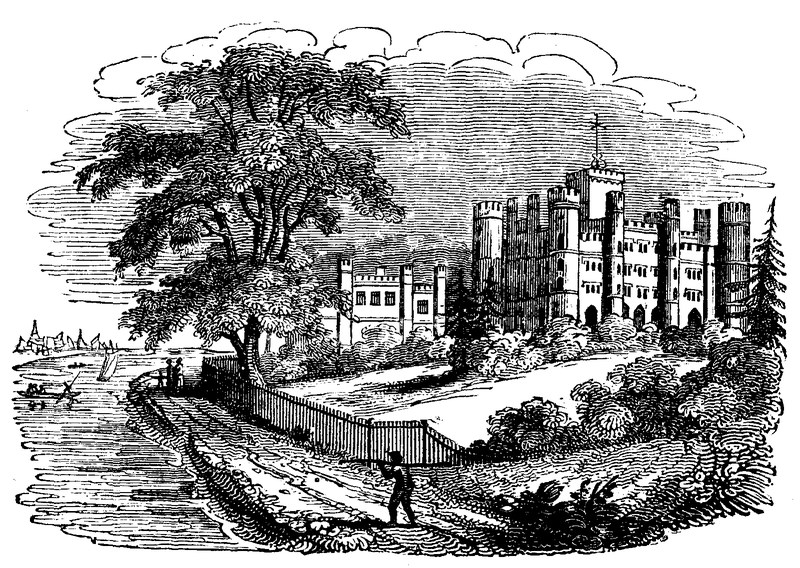

KEW PALACE

Innumerable are the instances of princes having sought to perpetuate their memories by the building of palaces, from the Domus Aurea, or golden house of Nero, to the comparatively puny structures of our own times. As specimens of modern magnificence and substantial comfort, the latter class of edifices may be admirable; but we are bound to acknowledge, that in boldness and splendour of design, they cannot assimilate to the labours of antiquity, much of whose stupendous character is to this day preserved in many series of interesting ruins:—

Whilst in the progress of the long decay,Thrones sink to dust, and nations pass away.As a record of this degeneracy, near the western corner of Kew Green stands the new palace, commenced for George III., under the direction of the late James Wyatt, Esq. The north front, the only part open to public inspection, possesses an air of solemn, sullen grandeur; but it very ill accords with the taste and science generally displayed by its nominal architect.

To quote the words of a contemporary, "this Anglo-Teutonic, castellated, gothized structure must be considered as an abortive production, at once illustrative of bad taste and defective judgment. From the small size of the windows and the diminutive proportion of its turrets, it would seem to possess

"'Windows that exclude the light,And passages that lead to nothing.'"Upon the unhappy seclusion of the royal architect, the works were suspended, and it now remains unfinished. Censure and abuse have, however, always been abundantly lavished on its architecture, whether it be the result of royal caprice or of professional study; but the taste of either party deserves to be taxed with its demerits.

The northern front was intended to be appropriated to the use of domestics; the whole building is rendered nearly indestructible by fire, by means of cast-iron joists and rafters, &c., certainly in this case an unnecessary precaution, since the whole pile is shortly to be pulled down. The foundation, too, is in a bog close to the Thames, and the principal object in its view is the dirty town of Brentford, on the opposite side of the river; a selection, it would seem, of family taste, for George II. is known to have often said, when riding through Brentford, "I do like this place, it's so like Yarmany."

A modern tourist, in "A Morning's Walk from London to Kew," characterizes the new palace as "the Bastile palace, from its resemblance to that building, so obnoxious to freedom and freemen. On a former occasion," says he, "I have viewed its interior, and I am at a loss to conceive the motive for preferring an external form, which rendered it impracticable to construct within it more than a series of large closets, boudoirs, and rooms like oratories." The latter part of this censure is judiciously correct; but the epithet "bastile" is perhaps too harsh for some ears.

The old palace at Kew formerly belonged to the Capel family, and by marriage became the property of Samuel Molyneux, Esq., secretary to George II. when prince of Wales. The late Frederic, prince of Wales, took a long lease of the house, which he made his frequent residence; and here, too, occasionally resided his favourite poet, James Thomson, author of "The Seasons." It is now held by his majesty on the same tenure. The house contains some good pictures, among which is a set of Canaletti's works; the celebrated picture of the Florence gallery, by Zoffany, (who resided in the neighbourhood,) was removed several years since. The pleasure-grounds, which contain 120 acres, were laid out by Sir William Chambers, one of the greatest masters of ornamental English gardening. Altogether they form a most delightful suburban retreat, and we hope to take an early opportunity of noticing them more in detail.

The old mansion opposite the palace was taken on a long lease by Queen Caroline of the descendants of Sir Richard Lovett, and has been inhabited by different branches of the royal family: and here his present majesty was educated, under the superintendance of the late Dr. Markham, archbishop of York. This house was bought, in 1761, for the late Queen Charlotte, who died here November 17, 1818.

Apart from these courtly attractions, Kew is one of the most interesting of the villages near London. On Kew Green once stood a house, the favourite retirement of Sir Peter Lely. In the church and cemetery, too, are interred Meyer, the celebrated miniature-painter, Gainsborough, and Zoffany. Their tombs are simple and unostentatious; but other and more splendid memorials are left to record their genius.

The premature fate of Kew Palace renders it at this moment an object of public curiosity; while the annexed engraving may serve to identify its site, when posterity

"Asks where the fabric stood."

THE NUPTIAL CHARM

(For the Mirror.)There is a charm in wedded bliss.That leaves each rapture cold to this;There is a soft endearing spell,That language can but faintly tell.'Tis not the figure, form, nor face,'Tis not the manner, air, nor grace,'Tis not the smile nor sparkling eye,'Tis not the winning look nor sigh.There is a charm surpassing these,A pleasing spell-like pleasure's breeze!A joy that centres in the heart,And doth its balmy sweets impart!'Tis not the lure of beauty's power,The skin-deep magnet of an hour;It is—affection's mutual glow,That does the nuptial charm bestow!UTOPIA.FINE ARTS

RAPHAEL SANZIO D'URBINO

In No. 273 of the Mirror, P.T.W. has noticed the Cartoons of Raphael; and I therefore solicit the reader's attention to the subjoined remarks on that master's unsurpassed genius.

Raphael Sanzio d'Urbino was the pupil of Pietro Perugino, but afterwards studied the works of Leonardo di Vinci and Michael Angelo. He excelled every modern painter, and was thought to equal the ancients; though he did not design naked figures with so much knowledge as Michael Angelo, who was more eminently skilled in anatomy; neither did he paint in so graceful a style as the Venetians; but he had a much more happy manner of disposing and choosing his subjects than any other artist who has lived since his time. His admirable choice of attitudes, ornaments, draperies, and expression, can surely never be equalled by the most successful aspirant in the fine arts. He has an undisputed title to the prince of painters; for, notwithstanding his premature death, he produced the most enchanting representations of the sublime and beautiful. A painter will ever derive much benefit from the study of all Raphael's pictures; especially from the Martyrdom of Saint Felicitas; the Transfiguration; Joseph explaining Pharaoh's Dream; and the School of Athens. Among the wonders of art with which the School of Athens abounds, we may select that of four youths attending to a sage mathematician, who is demonstrating some theorem. One of the boys is listening with profound reverence to the reasoning of his master; another discovers a greater quickness of apprehension; while the third is endeavouring to explain it to the last, who stands with a gaping countenance, utterly unable to comprehend the learned man's discourse. Expression, which was Raphael's chief excellence, and in which no other master has well succeeded, may be seen in the above picture to perfection. Besides his grand historical works, he executed portraits in a good style; and was also an admirable architect. In person, he was handsome, and remarkably well made, his manners being polite and unaffected. He never refused to impart to others what he knew himself; by which conduct he became esteemed in private, as much as he was adored in public.

This master's grand works are principally at Rome, in the Vatican; in the palace, Florence; Versailles; and the Palais Royal, France; the king's collection, Naples; and in the apartments at Hampton Court Palace. His best scholars were Julio Romano, Polydore, Giovanni d'Udine, and Gaudenzio, to all of whom he communicated the grand arcana of his wonderful art.

G.W.N.

RETROSPECTIVE GLEANINGS

Letter from the Princess, afterwards Queen, Elizabeth, to her sister, Queen Mary, on her being ordered to the Tower, in consequence of a suspicion that she was connected with Wyat's rebellion:—

"If any ever did try this old saynge, that a kinge's worde was more than another man's othe, I most humbly beseche your majesty to verefie it in me, and to remember your last promis and my last demande, that I be not condemned without answer and due profe: wiche it semes that now I am, for that without cause provid I am by your counsel frome you commanded to go unto the Tower; a place more wonted for a false traitor, than a tru subject. Wiche thogth I knowe I deserve it not, yet in the face of al this realme aperes that it is provid; wiche I pray God, I may dy the shamefullist dethe that ever any died, afore I may mene any suche thinge: and to this present hower I protest afor God (who shal juge my trueth whatsoever malice shal devis) that I never practised, consiled, nor consentid to any thinge that might be prejudicial to your parson any way, or daungerous to the State by any mene. And therefor I humbly beseche your Majestie to let me answer afore your selfe, and not suffer me to trust to your counselors; yea and that afore I go to the Tower, if it be possible; if not, afore I be further condemned. Howbeit, I trust assuredly, your Highnes to wyl give me leve to do it afor I go; for that thus shamfully I may not be cried out on, as now I shalbe; yea and without cause. Let consciens move your Highnes take some bettar way with me, than to make me be condemned in al mens sigth, afor my desert knowen. Also I most humbly beseche your Highnes to pardon this my boldnes, wiche innocency procures me to do, togither with hope of your natural kindnes; wiche I trust wyl not se me cast away without desert: wiche what it is, I wold desier no more of God, but that you truly knewe. Wiche thinge I thinke and beleve you shal never by report knowe, unless by your selfe you hire. I have harde in my time of many cast away, for want of comminge to the presence of ther Prince: and in late days I harde my Lorde of Sommerset say, that if his brother had bine sufferd to speke with him, he had never sufferd: but the perswasions wer made to him so gret, that he was brogth in belefe that he coulde not live safely if the Admiral lived; and that made him give his consent to his dethe. Thogth thes parsons ar not to be compared to your majestie, yet I pray God, as ivel perswations perswade not one sistar again the other; and al for that the have harde false report, and not harkene to the trueth knowin. Therefor ons again, kniling with humblenes of my hart, bicause I am not sufferd to bow the knees of my body, I humby crave to speke with your higthnis; wiche I wolde not be so bold to desier, if I knewe my selfe most clere as I knowe myselfe most tru. And as for the traitor Wiat, he migth paraventur writ me a lettar; but, on my faithe, I never receved any from him. And as for the copie of my lettar sent to the Frenche kinge, I pray God confound me eternally, if ever I sent him word, message, token, or lettar by any menes: and to this my truith I will stande in to my dethe.

Your Highnes most faithful subject that hathe bine from the beginninge, and wylbe to my ende,

ELIZABETH.

I humbly crave but only one worde of answer from your selfe.

Ellis's Original Letters.

THE NOVELIST

THE MUTINY

——O God!Had you but seen his pale, pale blanched cheek!He would not eat.—O Christ!THE BERYL.In the summer of the year 18—, I was the only passenger on board the merchantman, Alceste, which was bound to the Brazils. One fine moonlight night, I stood on the deck, and gazed on the quiet ocean, on which the moon-beams danced. The wind was so still, that it scarcely agitated the sails, which were spread out to invite it. I looked round; it was the same on every side—a world of waters: not a single object diversified the view, or intercepted the long and steady glance which I threw over the ocean. I have heard many complain of the sameness and unvarying uniformity of the objects which oppose themselves to the eye of the voyager. I feel differently; I can gaze for hours, without weariness, on the deep, occupied with the thought it produces; I can listen to the rush of the element as the vessel cleaves it, and these things have charms for me which others cannot perceive.

I heard, on a sudden, a noise, which seemed to proceed from the captain's cabin, and I thought I could distinguish the voices of several men, speaking earnestly, though in a suppressed tone. I cautiously drew near the spot from whence the noise arose, but the alarm was given, and I could see no one. I retired to rest, or rather to lie down; for I felt that heavy and foreboding sense of evil overpower me, which comes we know not how or wherefore; and I could not sleep, knowing that there had been disputes between the captain and his men, respecting some point of discipline, and I feared to think what might be the consequences. I lay a long time disturbed with these unpleasant reflections; at last, wearied with my thoughts, my eyes closed, and I dropped to sleep. But it was not to that refreshing sleep which recruits the exhausted spirits, and by awhile "steeping the senses in forgetfulness," renders them fitter for exertion on awakening. My sleep was haunted with hideous and confused dreams, and murder and blood seemed to surround me. I was awakened by convulsive starts, and in vain sought again for quiet slumber; the same images filled my mind, diversified in a thousand horrid forms. Early in the morning, I arose, and went above, and the mild sea breeze dispelled my uneasy sensations.

During the whole of the day nothing seemed to justify the fears that had tormented me, and everything went on in its regular course. The men pursued their occupations quietly and in silence, and I thought the temporary fit of disaffection was passed over. Alas! I remembered not that the passions of men, like deep waters, are most to be suspected when they seem to glide along most smoothly. Night came on, and I retired to rest more composed than on the preceding evening. I endeavoured to convince myself that the noises I had heard were but the fancies of a disturbed imagination, and I slept soundly. Ill-timed security! About midnight I was awakened by a scuffling in the vessel. I hastened to the spot; the captain and one of his officers were fighting against a multitude of the ship's crew. In a moment after I saw the officer fall. Two fellows advanced to me, and, clapping pistols to my breast, threatened instant death, if I stirred or spoke. I gazed on the bloody spectacle; the bodies, which lay around, swimming in gore, testified that the mutineers could not have accomplished their aim with impunity. I was horror-struck; a swimming sensation came over my eyes, my limbs failed me, and I fell senseless.

When I recovered, I found myself lying on a bed. Everything was still. I listened in vain for a sound; I lay still a considerable time; at last, I arose and walked about the ship, but could see no one. I searched every part of the vessel; I visited the place of slaughter, which I had, at first, carefully avoided; I counted nine dead bodies, and the coagulated blood formed a loathsome mass around them; I shuddered to think I was desolate—the companion of death. "Good God!" said I, "and they have left me here alone!" The word sounded like a knell to me. It now occurred to me, it was necessary the bodies should be thrown overboard. I took up one of them, dragged it to the side, and plunged it into the waves; but the dash of the heavy body into the sea, reminded me more forcibly of my loneliness. The sea was so calm, I could scarcely hear it ripple by the vessel's side. One by one I committed the bodies to their watery grave. At last my horrible task was finished. My next work was to look for the ship's boats, but they were gone, as I expected. I could not bear to remain in the ship; it seemed a vast tomb for me. I resolved to make some sort of raft, and depart in it. This occupied two or three days; at length it was completed, and I succeeded in setting it afloat.

I lowered into it all the provision I could find in the ship, which was but little, the sailors having, as I imagined, carried off the remainder. All was ready, and I prepared to depart. I trembled at the thought of the dangers I was about to encounter. I was going to commit myself to the ocean, separated from it only by a few boards, which a wave might scatter over the surface of the waters. I might never arrive at land, or meet with any vessel to rescue me from my danger, and I should be exposed, without shelter, and almost without food. I half resolved to remain in my present situation; but a moment's reflection dispelled the idea of such a measure. I descended; I stood on my frail raft; I cut the rope by which it was fastened to the ship. I was confused to think of my situation; I could hardly believe that I had dared to enter alone on the waste of waters. I endeavoured to compose myself, but in vain. As far as I could see, nothing presented itself to my view but the vessel I had left; the sea was perfectly still, for not the least wind was stirring. I endeavoured, with two pieces of board, which supplied the place of oars, to row myself along; but the very little progress I made alarmed me. If the calm should continue, I should perish of hunger. How I longed to see the little sail I had made, agitated by the breeze! I watched it from morning to night; it was my only employment; but in vain. The weather continued the same. Two days passed over; I looked at my store of provisions; it would not, I found, last above three or four days longer, at the farthest. They were quickly passing away. I almost gave myself up for lost. I had scarcely a hope of escaping.

On the fourth day since my departure from the ship, I thought I perceived something at a distance; I looked at it intently—it was a sail. Good heavens! what were my emotions at the sight! I fastened my handkerchief on a piece of wood, and waved it, in hopes that it would be observed, and that I should be rescued from my fearful condition. The vessel pressed on its course; I shouted;—I knew they could not hear me, but despair impelled me to try so useless an expedient. It passed on—it grew dim—I stretched my eyeballs to see it—it vanished—it was gone! I will not attempt to describe the torturing feelings which possessed me, at seeing the chance of relief which had offered itself destroyed. I was stupified with grief and disappointment. My stock of provisions was now entirely exhausted, and I looked forward with horror to an excruciating death.

A little water which had remained, quenched my burning thirst. I wished that the waves would rush over me. My hunger soon became dreadful, but I had no means of relieving it. I endeavoured to sleep, that I might for awhile, forget my torments; and my wearied frame yielded for awhile to slumber. When I awoke I was not, however, refreshed; I was weak, and felt a burning pain at my stomach. I became hourly more feeble; I lay down, but was unable to rise again. My limbs lost their strength; my lips and tongue were parched; a convulsive shuddering agitated me; my eyes seemed darkened, and I gasped for breath.

The burning at my stomach now departed; I experienced no pain; but a dull torpor came over me; my hands and feet became cold; I believed I was dying, and I rejoiced at the thought. Presently I lost all thought and feeling, and lay, without sense, on a few boards, which divided me from the ocean. In this situation, as I was afterwards informed, I was taken up by a small vessel, and carried to a seaport town. I slowly recovered, and found that I alone, of all who were on board the vessel in which I had embarked, had escaped death. The crew, who had departed in the boats, after murdering the captain, had met their reward—the boats were shattered against a rock.

December Tales.

THE SELECTOR, AND LITERARY NOTICES OF NEW WORKS

A STORM IN THE INDIAN SEAS

While the sun was setting with even more than its usual brilliancy, and leaving its path marked with streaks of gold, a bird hovered over our heads, and suddenly alighted on our taffrail: it was one of "Mother Carey's chickens," which by mariners are considered as harbingers of ill, and generally of a furious storm. At a warning of this kind I did not then feel disposed to take alarm; but there were other warnings not to be slighted—the horizon to the east presented the extraordinary appearance of a black cloud in the shape of a bow, with its convex towards the sea, and which kept its singular shape and position unchanged until nightfall. For the period too of twenty minutes after the setting of the sun, the clouds to the north-west continued of the colour of blood; but that which most attracted our observation was, to us, a remarkable phenomenon—the sea immediately around us, and, as far as the eye could discern by the light of the moon, appeared, for about forty minutes, of a perfectly milk white. We were visited by two more chickens of Mother Carey, both of which sought refuge, with our first visiter, on the mainmast. We sounded, but found no bottom at a hundred fathoms; a bucket of the water was then drawn up, the surface of which was apparently covered with innumerable sparks of fire—an effect said to be caused by the animalculae which abound in sea-water: it is at all times common, but the sparks are not in general so numerous, nor of such magnitude, as were those which then presented themselves. The hand too, being dipped in the water, and immediately withdrawn, thousands of them would seem to adhere to it. A dismal hollow breeze, which, as the night drew on, howled through our rigging, and infused into us all a sombre, melancholy feeling, increased by gathering clouds, and the altogether portentous state of the atmosphere and elements, ushered in the first watch, which was to be kept by Thomson.

About eight o'clock, loud claps of thunder, each in kind resembling a screech, or the blast of a trumpet, rather than the rumbling sound of thunder in Europe, burst over our heads, and were succeeded by vivid flashes of forked lightning. We now made every necessary preparation for a storm, by striking the top-gallant-masts, with their yards, close reefing the topsails and foresail, bending the storm-staysail, and battening down the main hatch, over which two tarpaulins were nailed, for the better preservation of the cargo. We observed innumerable shoals of fishes, the motions of which appeared to be more than usually vivid and redundant.

At twelve o'clock, on my taking charge of the deck, the scene bore a character widely different from that which it presented but three hours before. We now sailed under close-reefed maintopsail and foresail. The sea ran high; our bark laboured hard, and pitched desperately, and the waves lashed her sides with fury, and were evidently increasing in force and size. Over head nothing was to be seen but huge travelling clouds, called by sailors the "scud," which hurried onwards with the fleetness of the eagle in her flight. Now and then the moon, then in her second quarter, would show her disc for an instant, but be quickly obscured; or a star of "paly" light peep out, and also disappear. The well was sounded, but the vessel did not yet make more water than what might be expected in such a sea; we, however, kept the pumps going at intervals, in order to prevent the cargo from sustaining damage. The wind now increased, and the waves rose higher; about two o'clock A.M. the weather maintopsail-sheet gave way; the sail then split to ribbons, and before we could clue it up, was completely blown away from the bolt-rope. The foresail was then furled, not without great difficulty, and imminent hazard to the seamen, the storm staysail alone withstanding the mighty wind, which seemed to gain strength every half-hour, while the sea, in frightful sublimity, towered to an incredible height, frequently making a complete breach over our deck.