полная версия

полная версияNotes and Queries, Number 12, January 19, 1850

Various

Notes and Queries, Number 12, January 19, 1850

NOTES

ORIGIN OF A WELL-KNOWN PASSAGE IN HUDIBRAS

The often-quoted lines—

"For he that fights and runs awayMay live to fight another day,"generally supposed to form a part of Hudibras, are to be found (as Mr. Cunningham points out, at p. 602. of his Handbook for London), in the Musarum Deliciæ, 12mo. 1656; a clever collection of "witty trifles," by Sir John Mennis and Dr. James Smith.

The passage, as it really stands in Hudibras (book iii. canto iii. verse 243.), is as follows:—

"For those that fly may fight again,Which he can never do that's slain."But there is a much earlier authority for these lines than the Musarum Deliciæ; a fact which I learn from a volume now open before me, the great rarity of which will excuse my transcribing the title-page in full:—

"Apophthegmes, that is to saie, prompte, quicke, wittie, and sentencious saiynges, of certain Emperours, Kynges, Capitaines, Philosophiers, and Oratours, as well Grekes as Romaines, bothe veraye pleasaunt and profitable to reade, partely for all maner of persones, and especially Gentlemen. First gathered and compiled in Latine by the right famous clerke, Maister Erasmus, of Roteradame. And now translated into Englyshe by Nicolas Udall. Excusam typis Ricardi Grafton, 1542. 8vo."

A second edition was printed by John Kingston, in 1564, with no other variation, I believe, than in the orthography. Haslewood, in a note on the fly-leaf of my copy, says:—

"Notwithstanding the fame of Erasmus, and the reputation of his translator, this volume has not obtained that notice which, either from its date or value, might be justly expected. Were its claim only founded on the colloquial notes of Udall, it is entitled to consideration, as therein may be traced several of the familiar phrases and common-place idioms, which have occasioned many conjectural speculations among the annotators upon our early drama."

The work consists of only two books of the original, comprising the apophthegms of Socrates, Aristippus, Diogenes, Philippus, Alexander, Antigonus, Augustus Cæsar, Julius Cæsar, Pompey, Phocion, Cicero, and Demosthenes.

On folio 239. occurs the following apophthegm, which is the one relating to the subject before us:—

"That same man, that renneth awaie,May again fight, on other daie."¶ Judgeyng that it is more for the benefite of one's countree to renne awaie in battaile, then to lese his life. For a ded man can fight no more; but who hath saved hymself alive, by rennyng awaie, may, in many battailles mo, doe good service to his countree.

"§ At lest wise, if it be a poinet of good service, to renne awaie at all times, when the countree hath most neede of his helpe to sticke to it."

Thus we are enabled to throw back more than a century these famous Hudibrastic lines, which have occasioned so many inquiries for their origin.

I take this opportunity of noticing a mistake which has frequently been made concerning the French translation of Butler's Hudibras. Tytler, in his Essay on Translation; Nichols, in his Biographical Anecdotes of Hogarth; and Ray, in his History of the Rebellion, attributes it to Colonel Francis Towneley; whereas it was the work of John Towneley, uncle to the celebrated Charles Towneley, the collector of the Marbles.

EDWARD F. RIMBAULT.FIELD OF THE BROTHERS' FOOTSTEPS

I do not think that Mr. Cunningham, in his valuable work, has given any account of a piece of ground of which a strange story is recorded by Southey, in his Common-Place Book (Second Series, p. 21.). After quoting a letter received from a friend, recommending him to "take a view of those wonderful marks of the Lord's hatred to duelling, called The Brothers' Steps," and giving him the description of the locality, Mr. Southey gives an account of his own visit to the spot (a field supposed to bear ineffaceable marks of the footsteps of two brothers, who fought a fatal duel about a love affair) in these words:—"We sought for near half an hour in vain. We could find no steps at all, within a quarter of a mile, no nor half a mile, of Montague House. We were almost out of hope, when an honest man who was at work directed us to the next ground adjoining to a pond. There we found what we sought, about three quarters of a mile north of Montague House, and about 500 yards east of Tottenham Court Road. The steps answer Mr. Walsh's description. They are of the size of a large human foot, about three inches deep, and lie nearly from north-east to south-west. We counted only seventy-six, but we were not exact in counting. The place where one or both the brothers are supposed to have fallen, is still bare of grass. The labourer also showed us the bank where (the tradition is) the wretched woman sat to see the combat."

Mr. Southey then goes on the speak of his full confidence in the tradition of their indestructibility, even after ploughing up, and of the conclusions to be drawn from the circumstance.

To this long note, I beg to append a query, as to the latest account of these footsteps, previous to the ground being built over, as it evidently now must be.

G.H.B.ON AUTHORS AND BOOKS, NO. 4

Verse may picture the feelings of the author, or it may only picture his fancy. To assume the former position, is not always safe; and in two memorable instances a series of sonnets has been used to construct a baseless fabric of biography.

In the accompanying sonnet, there is no such uncertainty. It was communicated to me by John Adamson, Esq., M.R.S.L., &c., honourably known by a translation of the tragedy of Dona Ignez de Castro, from the Portuguese of Nicola Luiz, and by a Memoir of the life and writings of Camoens, &c. It was not intended for publication, but now appears, at my request.

Mr. Adamson, it should be stated, is a corresponding member of the Royal Academy of Sciences of Lisbon, and has received diplomas of the orders of Christ and the Tower-and-Sword. The coming storm alludes to the menace of invasion by France.

"SONNET"O Portugal! whene'er I see thy nameWhat proud emotions rise within my breast!To thee I owe—from thee derive that fameWhich here may linger when I lie at rest.When as a youth I landed on thy shore,How little did I think I e'er could beWorthy the honours thou has giv'n to me;And when the coming storm I did deplore,Drove me far from thee by its hostile threat—With feelings which can never be effaced,I learn'd to commune with those writers oldWho had the deeds of they great chieftains told;Departed bards in converse sweet I met,I'd seen where they had liv'd—the land Camoens grac'd."I venture to add the titles of two interesting volumes which have been printed subsequently to the publications of Lowndes and Martin. It may be a useful hint to students and collectors:—

"BIBLIOTHECA LUSITANA, or catalogue of books and tracts, relating to the history, literature, and poetry, of Portugal: forming part of the library of John Adamson, M.R.S.L. etc. Newcastle on Tyne, 1836. 8vo.

"LUSITANIA ILLUSTRATA; notices on the history, antiquities, literature, etc. of Portugal. Literary department. Part I. Selection of sonnets, with biographical Sketches of the author, by John Adamson, M.R.S.L. etc. Newcastle upon Tyne, 1842. 8vo."

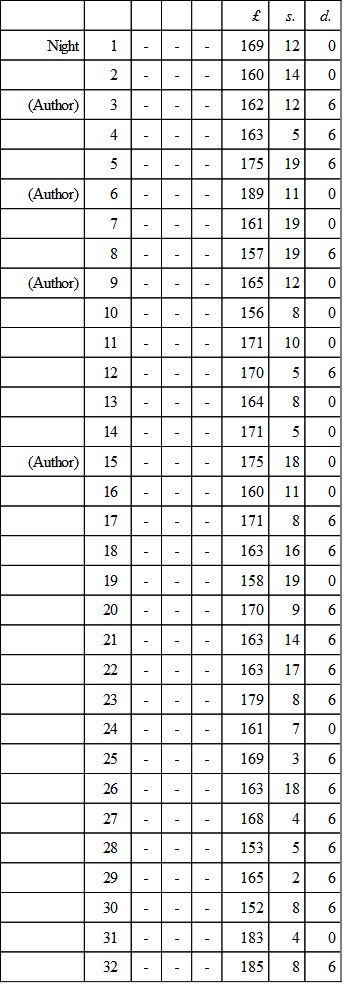

BOLTON CORNEY.RECEIPTS TO THE BEGGAR'S OPERA ON ITS PRODUCTION

Every body is aware of the prodigious and unexpected success of Gay's Beggar's Opera on its first production; it was offered to Colley Cibber at Drury Lane, and refused, and the author took it to Rich, at the Lincoln's-Inn-Fields theatre, by whom it was accepted, but not without hesitation. It ran for 62 nights (not 63 nights, as has been stated in some authorities) in the season of 1727–1728; of these, 32 nights were in succession; and, from the original Account-book of the manager, C.M. Rich, I am enabled to give an exact statement of the money taken at the doors on each night, distinguishing such performances as were for the benefit of the author, viz. the 3rd, 6th, 9th, and 15th nights, which put exactly 693l. 13s. 6d. into Gay's pocket. This is a new circumstance in the biography of one of our most fascinating English writers, whether in prose or verse. Rich records that the king, queen, and princesses were present on the 21st repetition, but that was by no means one of the fullest houses. The very bill sold at the doors on the occasion has been preserved, and hereafter may be furnished for the amusement of your readers. It appears, that when the run of the Beggar's Opera was somewhat abruptly terminated by the advance of the season and the benefits of the actors, the "takings," as they were and still are called, were larger than ever. The performances commenced on 29th January, 1728, and that some striking novelty was required at the Lincoln's-Inn-Fields theatre, to improve the prospects of the manager, may be judged from the fact that the new tragedy of Sesostris, brought out on the 17th January, was played for the benefit of its author (John Sturm) on its 6th night to only 58l. 19s., while the house was capable of holding at least 200l.

In the following statement of the receipts to the Beggar's Opera, I have not thought it necessary to insert the days of the months:—

Therefore, when the run was interrupted, the attraction of the opera was greater than it had been on any previous night, excepting the 6th, which was one of those set apart for the remuneration of the author, when the receipt was 189l. 11s. The total sum realised by the 32 successive performances was 5351l. 15s., of which, as we have already shown, Gay obtained 693l. 13s 6d. To him it was all clear profit; but from the sum obtained by Rich are, of course, to be deducted the expenses of the company, lights, house-rent, &c.

The successful career of the piece was checked, as I have said, by the intervention of benefits, and the manager would not allow it to be repeated even for Walker's and Miss Fenton's nights, the Macheath and Polly of the opera; but, in order to connect the latter with it, when Miss Fenton issued her bill for The Beaux's Stratagem, on 29th April, it was headed that it was "for the benefit of Polly." An exception was, however, made in favour of John Rich, the brother of the manager, for whose benefit the Beggar's Opera was played on 26th February, when the receipt was 184l. 15s. Miss Fenton was allowed a second benefit, on the 4th May, in consequence, we may suppose, of her great claims in connection with the Beggar's Opera, and then it was performed to a house containing 155l. 4s. The greatest recorded receipt, in its first season, was on the 13th April, when, for some unexplained cause the audience was so numerous that 198l. 17s. were taken at the doors.

After this date there appears to have been considerable fluctuation in the profits derived from repetitions of the Beggar's Opera. On the 5th May, the day after Polly Fenton's (her real name was Lavinia) second benefit, the proceeds fell to 78l. 14s., the 50th night produced 69l. 12s., and the 51st only 26l. 1s. 6d. The next night the receipt suddenly rose again to 134l. 13s. 6d., and it continued to range between 53l. and 105l. until the 62nd and last night (19th June), when the sum taken was 98l. 17s. 6d.

Miss Fenton left the stage at the end of the season, to be made Duchess of Bolton, and in the next season her place, as regards the Beggar's Opera, was taken by Miss Warren, and on 20th September it attracted 75l. 7s.; at the end of November it drew only 23l., yet, on the 11th December, for some reason not stated by the manager, the takings amounted to 112l. 9s. 6d. On January 1st a new experiment was tried with the opera, for it was represented by children, and the Prince of Wales commanded it on one or more of the eight successive performances it thus underwent. On 5th May we find Miss Cantrell taking Miss Warren's character, and in the whole, the Beggar's Opera was acted more than forty times in its second year, 1728–9, including the performances by "Lilliputians" as well as comedians. This is, perhaps, as much of its early history as your readers will care about.

DRAMATICUS.NOTES UPON CUNNINGHAM'S HANDBOOK FOR LONDON

Lady Dacre's Alms-Houses, or Emanuel Hospital.—"Jan. 8. 1772, died, in Emanual Hospital, Mrs. Wyndymore, cousin of Mary, queen of William III., as well as of Queen Anne. Strange revolution of fortune, that the cousin of two queens should, for fifty years, by supported by charity."—MS. Diary, quoted in Collett's Relics of Literature, p. 310.

Essex Buildings.—"On Thursday next, the 22nd of this instant, November, at the Musick-school in Essex Buildings, over against St. Clement's Church in the Strand, will be continued a concert of vocal and instrumental musick, beginning at five of the clock, every evening. Composed by Mr. Banister."—Lond. Gazette, Nov. 18. 1678. "This famous 'musick-room' was afterwards Paterson's auction-room."—Pennant's Common-place Book.

St. Antholin's.—In Thorpe's Catalogue of MSS. for 1836 appears for sale, Art. 792., "The Churchwarden's Accounts, from 1615 to 1752, of the Parish of St. Antholin's, London." Again, in the same Catalogue, Art. 793., "The Churchwardens and Overseers of the Parish of St. Antholin's, in London, Accounts from 1638 to 1700 inclusive." Verily these books have been in the hands of "unjust stewards!"

Clerkenwell.—Names of eminent persons residing in this parish in 1666:—Earl of Carlisle, Earl of Essex, Earl of Aylesbury, Lord Barkely, Lord Townsend, Lord Dellawar, Lady Crofts, Lady Wordham, Sir John Keeling, Sir John Cropley, Sir Edward Bannister, Sir Nicholas Stroude, Sir Gower Barrington, Dr. King, Dr. Sloane. In 1667-8:—Duke of Newcastle, Lord Baltimore, Lady Wright, Lady Mary Dormer, Lady Wyndham, Sir Erasmus Smith, Sir Richard Cliverton, Sir John Burdish, Sir Goddard Nelthorpe, Sir John King, Sir William Bowles, Sir William Boulton.—Extracted from a MS. in the late Mr. Upcott's Collection.

Tyburn Gallows.—No. 49. Connaught Square, is built on the spot where this celebrated gallows stood; and, in the lease granted by the Bishop of London, this is particularly mentioned.

EDWARD F. RIMBAULT.SEWERAGE IN ETRURIA

I have been particularly struck, in reading The Cities and Cemeteries of Etruria, of George Dennis, by the great disparity there appears between the ancient population of this country and the present.

The ancient population appears, moreover, to have been located in circumstances not by any means favourable to the health of the people. Those cities surrounded by high walls, and entered by singularly small gateways, must have been very badly ventilated, and very unfavourable to health; and yet it is not reasonable to suppose they could have been so unhealthy then as the author describes the country at present to be. It is hardly possible to imagine so great a people as the Etruscans, the wretched fever-stricken objects the present inhabitants of the Maremna are described to be.

To what, then, can this great difference be ascribed? The Etruscans appear to have taken very great pains with the drainage of their cities; on many sites the cloaca are the only remains of their former industry and greatness which remain. They were also careful to bury their dead outside their city walls; and it is, no doubt, to these two circumstances, principally, that their increase and greatness, as a people, are to be ascribed. But why do not the present inhabitants avail themselves of the same means to health? Is it that they are idle, or are they too broken spirited and poverty-stricken to unite in any public work? Or has the climate changed?

Perhaps it was owing to some defect in their civil polity that the ancients were comparatively so easily put down by the Roman power, which might have been the superior civilisation. Possibly the great majority of the people may have been dissatisfied with their rulers, and gladly removed to another place and another form of government. It is even possible, and indeed likely, that these great public works may have been carried on by the forced labour of the poorest and, consequently, the most numerous class of the population, and that, consequently, they had no particular tie to their native city, as being only a hardship to them; and they may even have had a dislike to sewers in themselves, as reminding them of their bondage, and which dislike their descendants have inherited, and for which they are now suffering. At any rate, it is an instructive example to our present citizens of the value of drainage and sanitary arrangements, and shows that the importance of these things was recognised and appreciated in the earliest times.

C.P.F.ANDREW FRUSIUS—ANDRÉ DES FREUX

Many of your readers, as well as "ROTERODAMUS," will be ready to acknowledge their obligation to Mr. Bruce for his prompt identification of the author of the epigram against Erasmus (pp. 27, 28.). I have just referred to the catalogue of the library of this university, and I regret to say that we have no copy of any of the works of Frusius. Mr. Bruce says he knows nothing of Frusius as an author. I believe there is no mention of him in any English bibliographical or biographical work. There is, however, a notice of him in the Biographie Universelle, vol. xvi. (Paris), and in the Biografia Universale, vol. xxi. (Venezia). As these works have, perhaps, found their way into very few private English libraries, I send you the following sketch, which will probably be acceptable to your readers. It is much to be lamented that sufficient encouragement cannot be given in this country for the production of a Universal Biography. Roses's work, which promised to be a giant, dwindled down to a miserable pigmy; and that under "The Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge" was strangled in its birth.

André des Freux, better known by his Latin name, Frusius, was born at Chartres, in the beginning of the sixteenth century. He embraced the life of an ecclesiastic, and obtained the cure of Thiverval, which he held many years with great credit to himself. The high reputation of Ignatius Loyola, who was then at Rome, with authority from the Holy See to found the Society of the Jesuits, led Frusius to that city, where he was admitted a member of the new order in 1541, and shortly after became secretary to Loyola. He contributed to the establishment of the Society at Parma, Venice, and many towns of Italy and Sicily. He was the first Jesuit who taught the Greek language at Messina; he also gave public lectures on the Holy Scriptures in Rome. He was appointed Rector of the German College at Rome, shortly before his death, which occurred on the 25th of October, 1556, three months and six days after the death of Loyola. Frusius had studied, with equal success, theology, medicine, and law: he was a good mathematician, an excellent musician, and made Latin verses with such facility, that he composed them, on the instant, on all sorts of subjects. But these verses were neither so elegant nor so harmonious, as Alegambe asserts1, since he adds, that it requires close attention to distinguish them from prose. Frusius translated, from Spanish into Latin, the Spiritual Exercises of Loyola. He was the author of the following works:—Two small pieces, in verse, De Verborum et Rerum Copia, and Summa Latinæ Syntaxeos: these were published in several different places; Theses Collectæ ex Interpretatione Geneseos; Assertiones Theologicæ, Rome, 1554; Poemata, Cologne, 1558—this collection often reprinted at Lyons, Antwerp and Tournon, contains 2552 epigrams against the heretics, amongst whom he places Erasmus;—a poem De Agno Dei; and, lastly, another poem, entitled Echo de Presenti Christianæ Religionis Calamitate, which has been sometimes cited as an example of a great difficultè vaincue. The edition of Tournon contains also a poem, De Simplicitate, of which Alegambe speaks with praise. To Frusius was also owing an edition of Martial's Epigrams, divested of their obscenities.

EDW. VENTRIS.Cambridge, Jan. 10. 1850.

[Our valued correspondent, MR. MACCABE, has also informed us that the "Epigrams of Frusius were published at Antwerp, 1582, in 8vo., and at Cologne, 1641, in 12mo. See Feller's Biographie."]

OPINIONS RESPECTING BURNET

A small catena patrum has been given respecting Burnet, as a historian, in No. 3. pp. 40, 41., to which two more scriptorum judicia have been appended in No. 8. p. 120., by "I.H.M.". As a sadly disparaging opinion had been quoted, at p. 40., from Lord Dartmouth, I hope you will allow the following remarks on the testimony of that nobleman to appear in your columns:—

"No person has contradicted Burnet more frequently, or with more asperity, than Dartmouth. Yet Dartmouth wrote, 'I do not think he designedly published anything he believed to be false.' At a later period, Dartmouth, provoked by some remarks on himself in the second volume of the Bishop's history, retracted this praise; but to such a retraction little importance can be attached. Even Swift has the justice to say, 'After all he was a man of generosity and good nature.'"—Short Remarks on Bishop Burnet's History.

"It is usual to censure Burnet as a singularly inaccurate historian; but I believe the charge to be altogether unjust. He appears to be singularly inaccurate only because his narrative has been subjected to a scrutiny singularly severe and unfriendly. If any Whig thought it worth while to subject Reresby's Memoirs, North's Examen, Mulgrave's Account of the Revolution, or the Life of James the Second, edited by Clarke, to a similar scrutiny, it would soon appear that Burnet was far indeed from being the most inexact writer of his time."—Macaulay, Hist. England, vol. ii. p.177, 3rd. Ed.

T.Bath.

QUERIES

SAINT THOMAS OF LANCASTER

Sir,—I am desirous of information respecting the religious veneration paid to the memory of Thomas, Earl of Lancaster, cousin-german to King Edward the Second. He was taken in open rebellion against the King on the 16th of March, 1322, condemned by a court-martial, and executed, with circumstances of great indignity, on the rising ground above the castle of Pomfret, which at the time was in his possession. His body was probably given to the monks of the adjacent priory; and soon after his death miracles were said to be performed at his tomb, and at the place of execution; a curious record of which is preserved in the library of Corpus Christi College, at Cambridge, and introduced by Brady into his history of the period. About the same time, a picture or image of him seems to have been exhibited in St. Paul's Church, in London, and to have been the object of many offerings. A special proclamation was issued, denouncing this veneration of the memory of a traitor, and threatening punishment on those who encouraged it; and a statement is given by Brady of the opinions of an ecclesiastic, who thought it very doubtful how far this devotion should be encouraged by the Church, the Earl of Lancaster, besides his political offences, having been a notorious evil-liver.

As soon, however, as the King's party was subdued, and the unhappy sovereign, whose acts and habits had excited so much animosity, cruelly put to death, we find not only the political character of the Earl of Lancaster vindicated, his attainder reversed, his estates restored to his family, and his adherents re-established in all their rights and liberties, but within five weeks of the accession of Edward the Third, a special mission was sent to the Pope from the King, imploring the appointment of a commission to institute the proper canonical investigation for his admission into the family of saints. His character and his cause are described, in florid language, as having been those of a Christian hero; and the numberless miracles wrought in his name, and the confluence of pilgrims to his tomb, are presumed to justify his invocation.