полная версия

полная версияThe Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 13, No. 351, January 10, 1829

Various

The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction / Volume 13, No. 351, January 10, 1829

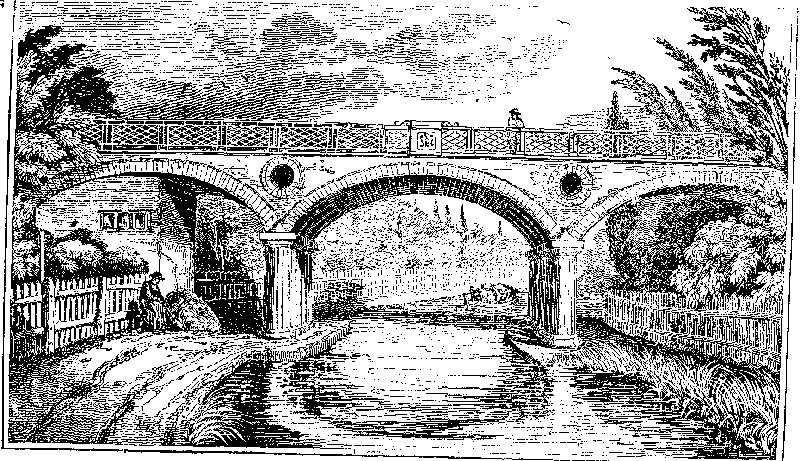

MACCLESFIELD BRIDGE, REGENT'S PARK

MACCLESFIELD BRIDGE

This picturesque structure crosses the Canal towards the Northern verge of the Regent's Park; and nearly opposite to it is a road leading to Primrose Hill, as celebrated in the annals of Cockayne as was the Palatino among the ancient Romans.

The bridge was built from the designs of Mr. Morgan, and its construction is considered to be "appropriate and architectural." Its piers are formed by cast-iron columns, of the Grecian Doric order, from which spring the arches, covering the towing-path, the canal itself, and the southern bank. The abacus, or top of the columns, the mouldings or ornaments of the capitals, and the frieze, are in exceeding good taste, as are the ample shafts. The supporters of the roadway, likewise, correspond with the order; although, says Mr. Elmes, the architect, "fastidious critics may object to the dignity of the pure ancient Doric being violated by degrading it into supporters of modern arches." The centre arch is appropriated to the canal and the towing-path, and the two external arches to foot-passengers, and as communications to the road above them. Mr. Elmes1 sums up the merits of the bridge as follows:—"It has a beautiful and light appearance, and is an improvement in execution upon a design of Perronet's for an architectural bridge, that is, a bridge of orders. The columns are well proportioned, and suitably robust, carrying solidity, grace, and beauty in every part; from the massy grandeur of the abacus, to the graceful revolving of the beautiful echinus, and to the majestic simplicity of the slightly indented flutings." He then suggests certain improvements in the design, which would have made the bridge "unexceptionably the most novel and the most tasteful in the metropolis. Even as it is, it is scarcely surpassed for lightness, elegance, and originality by any in Europe. It is of the same family with the beautiful little bridge in Hyde Park, between the new entrance and the barracks."

We are happy to quote the above praise on the construction of Macclesfield Bridge, inasmuch as a critical notice of many of the structures in the Regent's Park would subject them to much severe and merited censure. The forms of bridges admit, perhaps, of more display of taste than any other species of ornamental architecture, and of a greater means of contributing to the picturesque beauty of the surrounding scenery.

TRIBUTES TO THE DEAD, &c

(For the Mirror.)"When our friends we lose,Our alter'd feelings alter too our views;What in their tempers, teazed or distress'd,Is with our anger, and the dead at rest;And must we grieve, no longer trial made,For that impatience which we then display'd?Now to their love and worth of every kind,A soft compunction turns the afflicted mind;Virtues neglected then, adored become,And graces slighted, blossom on the tomb."CRABBE."It was the early wish of Pope," says Dr. Knox, "that when he died, not a stone might tell where he lay. It is a wish that will commonly be granted with reluctance. The affection of those whom we leave behind us is at a loss for methods to display its wonted solicitude, and seeks consolation under sorrow, in doing honour to all that remains. It is natural that filial piety, parental tenderness, and conjugal love, should mark, with some fond memorial, the clay-cold spot where the form, still fostered in the bosom, moulders away. And did affection go no farther, who could censure? But, in recording the virtues of the departed, either zeal or vanity leads to an excess perfectly ludicrous. A marble monument, with an inscription palpably false and ridiculously pompous, is far more offensive to true taste, than the wooden memorial of the rustic, sculptured with painted bones, and decked out with death's head in all the colours of the rainbow. There is an elegance and a classical simplicity in the turf-clad heap of mould which covers the poor man's grave, though it has nothing to defend it from the insults of the proud but a bramble. The primrose that grows upon it is a better ornament than the gilded lies on the oppressor's tombstone."

The Greeks had a custom of bedecking tombs with herbs and flowers, among which parsley was chiefly in use, as appears from Plutarch's story of Timoleon, who, marching up an ascent, from the top of which he might take a view of the army and strength of the Carthaginians, was met by a company of mules laden with parsley, which his soldiers conceived to be a very ill boding and fatal occurrence, that being the very herb wherewith they adorned the sepulchres of the dead. This custom gave birth to that despairing proverb, when we pronounce of one dangerously sick, that he has need of nothing but parsley; which is in effect to say, he's a dead man, and ready for the grave. All sorts of purple and white flowers were acceptable to the dead; as the amaranthus, which was first used by the Thessalians to adorn Achilles's grave. The rose, too, was very grateful; nor was the use of myrtle less common. In short, graves were bedecked with garlands of all sorts of flowers, as appears from Agamemnon's daughter in Sophocles:—

"No sooner came I to my father's tomb,But milk fresh pour'd in copious streams did flow,And flowers of ev'ry sort around were strow'd."Several other tributes were frequently laid upon graves, as ribands; whence it is said that Epaminondas's soldiers being disanimated at seeing the riband that hung upon his spear carried by the wind to a certain Lacedæmonian sepulchre, he bid them take courage, for that it portended destruction to the Lacedæmons, it being customary to deck the sepulchres of their dead with ribands. Another thing dedicated to the dead was their hair. Electra, in Sophocles, says, that Agamemnon had commanded her and Chrysosthemis to pay this honour:—

"With drink-off'rings and locks of hair we must,According to his will, his tomb adorn."It was likewise customary to perfume the grave-stones with sweet ointments, &c.

P.T.W.SONG

(For the Mirror.)I've roam'd the thorny path of life,And search'd abroad to find.Amid the blooming flowers so rife,That germ called peace of mind.At length a lovely lily caughtMy anxious, longing view,With all the sweets of "Heartsease" fraught,That fragrant flower was YOU.Thy smile to me is Heaven divine,Thy voice the soul of Love—In pity, then, sweet maid, be mine,My "heartsease" flow'ret prove.Nor wealth nor power would I attain,Though uncontrolled and free—All other joys to me are pain,When sever'd, love, from THEE.ELFORD.CHARLES BRANDON, AFTERWARDS DUKE OF SUFFOLK

(For the Mirror.)An event in the life of this nobleman gave Otway the plot for his celebrated tragedy of "The Orphan," though he laid the scene of his play in Bohemia. It is recorded in the "English Adventures," a very scarce pamphlet, published in 1667, only two or three copies of which are extant. The father of Charles Brandon retired, on the death of his lady, to the borders of Hampshire. His family consisted of two sons, and a young lady, the daughter of a friend, lately deceased, whom he adopted as his own child.

This lady being singularly beautiful, as well as amiable in her manners, attracted the affections of both the brothers. The elder, however, was the favourite, and he privately married her; which the younger not knowing, and overhearing an appointment of the lovers to meet the next night in her bed-chamber, he contrived to get his brother otherwise employed, and made the signal of admission himself, (thinking it a mere intrigue.) Unfortunately he succeeded.

On discovery, the lady lost her reason, and soon after died. The two brothers fought, and the elder fell. The father broke his heart a few months afterwards. The younger brother, Charles Brandon, the unintentional author of all this family misery, quitted England in despair, with a fixed determination of never returning.

Being abroad for several years, his nearest relations supposed him dead, and began to take the necessary steps for obtaining his estates; when, roused by this intelligence, he returned privately to England, and for a time took obscure lodgings in the vicinity of his family mansion.

While he was in this retreat, the young king, (Henry VIII.), who had just buried his father, was one day hunting on the borders of Hampshire, when he heard the cries of a female in distress in an adjoining wood. His gallantry immediately summoned him to the place, though he then happened to be detached from all his courtiers, where he saw two ruffians attempting to violate the honour of a young lady. The king instantly drew on them; and a scuffle ensued, which roused the reverie of Charles Brandon, who was taking his morning walk in an adjoining thicket. He immediately ranged himself on the side of the king, whom he then did not know; and by his dexterity, soon disarmed one of the ruffians, while the other fled.

The king, charmed with this act of gallantry, so congenial to his own mind, inquired the name and family of the stranger; and not only repossessed him of his patrimonial estates, but took him under his immediate protection.

It was this same Charles Brandon who afterwards privately married Henry's sister, Margaret, queen-dowager of France; which marriage the king not only forgave, but created him Duke of Suffolk, and continued his favour towards him to the last hour of the duke's life.

He died before Henry; and the latter showed, in his attachment to this nobleman, that notwithstanding his fits of capriciousness and cruelty, he was capable of a cordial and steady friendship. He was sitting in council when the news of Suffolk's death reached him; and he publicly took that occasion, both to express his own sorrow, and to celebrate the merits of the deceased. He declared, that during the whole course of their acquaintance, his brother-in-law had not made a single attempt to injure an adversary, and had never whispered a word to the disadvantage of any one; "and are there any of you, my lords, who can say as much?" When the king subjoined these words, (says the historian,) he looked round in all their faces, and saw that confusion which the consciousness of secret guilt naturally threw upon them.

Otway took his plot from the fact related in this pamphlet; but to avoid, perhaps, interfering in a circumstance which might affect many noble families at that time living, he laid the scene of his tragedy in Bohemia.

There is a large painting of the above incident now at Woburn, the seat of his Grace the Duke of Bedford; and the old duchess-dowager, in showing this picture a few years before her death to a nobleman, related the particulars of the story.

A CORRESPONDENT.THE TOPOGRAPHER

CARMARTHEN

(For the Mirror)The best or north-east view of Carmarthen comprises the bridge, part of the quay, with the granaries and shipping, and in the middle is seen part of the castle. Few towns can, perhaps, boast of greater antiquity, or of so many antiquarian remains as Carmarthen, South Wales; although, I am sorry to say, that their origin and history have not been, I believe, clearly explained or understood by the literary world. One would conclude, that as a Welshman is almost proverbially distinguished for deeming himself illustriously descended, and relating his long pedigree, he would naturally boast of, and exhibit to the public, some account of these vestiges of his ancestors; but such is not the case, and to their shame be it spoken, these ruins are scarcely noticed with any degree of interest by the inhabitants of Carmarthen. But to my subject. The name is derived from caera, wall, and marthen, a corruption of Merlyn, the name of its founder, who was a great necromancer and prophet, and held in high respect by the Welsh. There is a seat hewn out of a rock in a grove near this town, called Merlyn's Grove, where it is said he studied. He prophesied the fate of Wales, and said that Carmarthen would some day sink and be covered with water. I would concur with the author of a "Family Tour through the British Empire," by attributing his influence, not to any powers in magic, but to a superior understanding; although some of his predictions have been verified. The town of Carmarthen is pleasantly situated in a valley surrounded by hills; it has been fortified with walls and a castle, part of which remain; so that it appears to have been the residence of many princes of Wales. It has also been a Roman station, and has the remains of a Roman prætorium. Amongst its other antiquities are the Grey Friars, (a monastery,) the Bulwark, (a trench on the side of the town that fronts the river,) and the Priory. Its modern buildings are, the monument erected to Sir Thomas Picton, the Guildhall, the two gaols, a fish and butter market-place, over which is the town fire-bell; the slaughter-house, similar to the abattoir at Paris, and excellent shambles, with poultry and potato market-places annexed. The church, which is an ancient one, has an unattractive exterior; but when you enter it, I think you will say it can compete with any church for ancient beauty and ornament. Amongst the tombs in the chancel are those of Sir Rhys ap Thomas, with the effigies of him and his lady, affording a specimen of the costume of the reign of Henry VII.; and Sir Richard Steele, whose remains are discovered by a small, simple tablet. There is a promenade here, called the Parade, which commands a fine and extensive view of the surrounding picturesque scenery and of the Towy, where the coracles may be seen plying about. The town consists of ten principal streets, noted for being kept clean, and lighted with gas. It is governed by a mayor, two sheriffs, and twenty councilmen; sends a member to Parliament, and gives title of marquess to the family of Osborne. It carries on a great trade in butter and oats; and traffics much with Bristol by the river Towy, which runs into the sea; whence ships of two hundred tons burden come up to the town. The bay is very dangerous, owing to the bar and the quicksands. Its chief manufacture is tin, which is esteemed the best in the kingdom. It has a small theatre, in appearance a stable; but it is in contemplation to build a new one, as also a church; so that you will perceive the march of improvement is rapidly spreading into Wales, as well as other places.

W.H.P.S. Since I sent you an account of Picton's Monument at Carmarthen, it has been altered. The statue, bas-reliefs, and ornaments of the Picton Monument, have been bronzed by the direction of Mr. Nash, on his late visit to this town. Elegant as this column was before, the effect of the bronze, and a few other alterations, have so improved its appearance, as to make it seem a different structure. Nothing now remains to complete the outside but the names of the different actions in which Sir T. Picton was engaged during his honourable career. These are to be placed in bronzed letters on the base. A Latin inscription, already prepared, together with the arms and a bust of Picton, will ornament the inside of the building. It certainly is a monument worthy of the hero to whose memory it has been erected, and of the country by which it has been raised.

THE SKETCH BOOK

WATERLOO, THE DAY AFTER THE BATTLE

By an eye witness[For the following very interesting Narrative, our acknowledgments are due to the United Service Journal,—a work which has just started with the year, and to which, in the "customary" phrase, we wish "many happy returns."]

The summer of 1815 found me at Brussels. The town was then crowded to excess—it seemed a city of splendour; the bright and varied uniforms of so many different nations, mingled with the gay dresses of female beauty in the Park, and the Allée Verte was thronged with superb horses and brilliant equipages. The tables d'hôte resounded with a confusion of tongues which might have rivalled the Tower of Babel, and the shops actually glittered with showy toys hung out to tempt money from the pockets of the English, whom the Flemings seemed to consider as walking bags of gold. Balls and plays, routs and dinners were the only topics of conversation; and though some occasional rumours were spread that the French had made an incursion within the lines, and carried off a few head of cattle, the tales were too vague to excite the least alarm. I was then lodging with a Madame Tissand, on the Place du Sablon, and I occasionally chatted with my hostess on the critical posture of affairs. Every Frenchwoman loves politics, and Madame Tissand, who was deeply interested in the subject, continually assured me of her complete devotion to the English.—"Ces maudits François!" cried she one day, with almost terrific energy, when speaking of Napoleon's army. "If they should dare come to Brussels, I will tear their eyes out!"—"Oh, aunt!" sighed her pretty niece; "remember that Louis is a conscript!"—"Silence, Annette. I hate even my son, since he is fighting against the brave English!"—This was accompanied with a bow to me; but I own that I thought Annette's love far more interesting than Madame's Anglicism.

On the 3rd of June, I went to see ten thousand troops reviewed by the Dukes of Wellington and Brunswick. Imagination cannot picture any thing finer than the ensemble of this scene. The splendid uniforms of the English, Scotch, and Hanoverians, contrasted strongly with the gloomy black of the Brunswick Hussars, whose veneration for the memory of their old Duke, could be only be equalled by their devotion to his son. The firm step of the Highlanders seemed irresistible; and as they moved in solid masses, they appeared prepared to sweep away every thing that opposed them. In short, I was delighted with the cleanliness, military order, and excellent appointments of the men generally, and I was particularly struck with the handsome features of the Duke of Brunswick, whose fine, manly figure, as he galloped across the field, quite realized my beau ideal of a warrior. The next time I saw the Duke of Brunswick was at the dress ball, given at the Assembly-rooms in the Rue Ducale, on the night of the 15th of June. I stood near him when he received the information that a powerful French force was advancing in the direction of Charleroy. "Then it is high time for me to be off," said the Duke, and I never saw him alive again. The assembly broke up abruptly, and in half an hour drums were beating and bugles sounding. The good burghers of the city, who were almost all enjoying their first sleep, started from their beds at the alarm, and hastened to the streets, wrapped in the first things they could find. The most ridiculous and absurd rumours were rapidly circulated and believed. The most general impression seemed to be that the town was on fire; the next that the Duke of Wellington had been assassinated; but when it was discovered that the French were advancing, the consternation became general, and every one hurried to the Place Royale, where the Hanoverians and Brunswickers were already mustering.

About one o'clock in the morning of the 16th, the whole population of Brussels seemed in motion. The streets were crowded as in full day; lights flashed to and fro; artillery and baggage-wagons were creaking in every direction; the drums beat to arms, and the bugles sounded loudly "the dreadful note of preparation." The noise and bustle surpassed all description; here were horses plunging and kicking amidst a crowd of terrified burghers; there lovers parting from their weeping mistresses. Now the attention was attracted by a park of artillery thundering through the streets; and now, by a group of officers disputing loudly the demands of their imperturbable Flemish landlords; for not even the panic which prevailed could frighten the Flemings out of a single *stiver; screams and yells occasionally rose above the busy hum that murmured through the crowd, but the general sound resembled the roar of the distant ocean. Between two and three o'clock the Brunswickers marched from the town, still clad in the mourning which they wore for their old duke, and burning to avenge his death. Alas! they had a still more fatal loss to lament ere they returned. At four, the whole disposable force under the Duke of Wellington was collected together, but in such haste, that many of the officers had not time to change their silk stockings and dancing shoes; and some, quite overcome by drowsiness, were seen lying asleep about the ramparts, still holding, however, with a firm hand, the reins of their horses which were grazing by their sides. About five o'clock, the word "march" was heard in all directions, and instantly the whole mass appeared to move simultaneously. I conversed with several of the officers previous to their departure, and not one appeared to have the slightest idea of an approaching engagement. The Duke of Wellington and his staff did not quit Brussels till past eleven o'clock; and it was not till some time after they were gone, that it was generally known the whole French army, including a strong corps of cavalry, was within a few miles of Quatre Bras, where the brave Duke of Brunswick first met the enemy:

"And foremost fighting—fell."Dismay seized us all, when we found that a powerful French army was really within twenty-eight miles of us; and we shuddered at the thought of the awful contest which was taking place. For my own part, I had never been so near a field of battle before, and I cannot describe my sensations. We knew that our army had no alternative but to fly, or fight with a force four times stronger than its own: and though we could not doubt British bravery, we trembled at the fearful odds to which our men must be exposed. Cannon, lances, and swords, were opposed to the English bayonet alone. Cavalry we had none on the first day, for the horses had been sent to grass, and the men were scattered too widely over the country, to be collected at such short notice. Under these circumstances, victory was impossible; indeed, nothing but the stanch bravery, and exact discipline of the men, prevented the foremost of our infantry from being annihilated; and though the English maintained their ground during the day, at night a retreat became necessary. The agony of the British, resident at Brussels, during the whole of this eventful day, sets all language at defiance. No one thought of rest or food; but every one who could get a telescope, flew to the ramparts to strain his eyes, in vain attempts to discover what was passing. At length, some soldiers in French uniforms were seen in the distance; and as the news flew from mouth to mouth, it was soon magnified into a rumour that the French were coming. Horror seized the English and their adherents, and the hitherto concealed partizans of the French began openly to avow themselves; tri-coloured ribbons grew suddenly into great request, and cries of "Vive l'Empereur!" resounded through the air. These exclamations, however, were changed to "Vive le Lord Vellington!" when it was discovered that the approaching French came as captives, not conquerors.

Between seven and eight o'clock in the evening, I walked up to the Porte de Namur, where the wounded were just beginning to arrive. Fortunately some commodious caravans had arrived from England, only a few days before, and these were now entering the gate. They were filled principally with Brunswickers and Highlanders; and it was an appalling spectacle to behold the very soldiers, whose fine martial appearance and excellent appointments I had so much admired at the review, now lying helpless and mutilated—their uniforms soiled with blood and dirt—their mouths blackened with biting their cartridges, and all the splendour of their equipments entirely destroyed. When the caravans stopped, I approached them, and addressed a Scotch officer who was only slightly wounded in the knee.—"Are the French coming, sir?" asked I.—"Egad I can't tell," returned he. "We know nothing about it. We had enough to do to take care of ourselves. They are fighting like devils; and I'm off again as soon as my wound's dressed."—An English lady, elegantly attired, now rushed forwards—"Is my husband safe?" asked she eagerly.—"Good God! Madam," replied one of the men, "how can we possibly tell! I don't know the fate of those who were fighting by my side; and I could not see a yard round me." She scarcely heeded what he said; and rushed out of the gate, wildly repeating her question to every one she met. Some French prisoners now arrived. I noticed one, a fine fellow, who had had one arm shot off; and though the bloody and mangled tendons were still undressed, and had actually dried and blackened in the sun, he marched along with apparent indifference, carrying a loaf of bread under his remaining arm, and shouting "Vive l'Empereur!" I asked him if the French were coming.—"Je le crois bien," returned he, "preparez un souper, mes bourgeois—il soupera à Bruxelles ce soir."—Pretty information for me, thought I. "Don't believe him, sir," said a Scotchman, who lay close beside me, struggling to speak, though apparently in the last agony. "It's all right—I—assure—you—." The whole of Friday night was passed in the greatest anxiety; the wounded arrived every hour, and the accounts they brought of the carnage which was taking place were absolutely terrific. Saturday morning was still worse; an immense number of supernumeraries and runaways from the army came rushing in at the Porte de Namur, and these fugitives increased the public panic to the utmost. Sauve qui peut! now became the universal feeling; all ties of friendship or kindred were forgotten, and an earnest desire to quit Brussels seemed to absorb every faculty. To effect this object, the greatest sacrifices were made. Every beast of burthen, and every species of vehicle were put into requisition to convey persons and property to Antwerp. Even the dogs and fish-carts did not escape—enormous sums were given for the humblest modes of conveyance, and when all failed, numbers set off on foot. The road soon became choked up—cars, wagons, and carriages of every description were joined together in an immovable mass and property to an immense amount was abandoned by its owners, who were too much terrified even to think of the loss they were sustaining. A scene of frightful riot and devastation ensued. Trunks, boxes, and portmanteaus were broken open and pillaged without mercy; and every one who pleased, helped himself to what he liked with impunity. The disorder was increased by a rumour, that the Duke of Wellington was retreating towards Brussels, in a sort of running fight, closely pursued by the enemy; the terror of the fugitives now almost amounted to frenzy, and they flew like maniacs escaping from a madhouse. It is scarcely possible to imagine a more distressing scene. A great deal of rain had fallen during the night, and the unhappy fugitives were obliged literally to wade through mud. I had, from the first, determined to await my fate in Brussels; but on this eventful morning, I walked a few miles on the road to Antwerp, to endeavour to assist my flying countrymen. I was soon disgusted with the scene, and finding all my efforts to be useful, unavailing, I returned to the town, which now seemed like a city of the dead; for a gloomy silence reigned through the streets, like that fearful calm which precedes a storm; the shops were all closed, and all business was suspended. During the panic of Friday and Saturday, the sacrifice of property made by the British residents was enormous. A chest of drawers sold for five francs, a bed for ten, and a horse for fifty. In one instance, which fell immediately under my own observation, some household furniture was sold for one thousand francs, (about 40l.) for which the owner had given seven thousand francs, (280l.) only three weeks before. This was by no means a solitary instance; indeed in most cases, the loss was much greater, and in many, houses full of furniture were entirely deserted, and abandoned to pillage.