полная версия

полная версияThe Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 10, No. 286, December 8, 1827

The castle and all its rocks, in peristrephic panorama, then floated cloud-like by—and we saw the whole mile-length of Prince's-street stretched before us, studded with innumerable coaches, chaises, chariots, carts, wagons, drays, gigs, shandrydans, and wheel-barrows, through among which we dashed, as if they had been as much gingerbread—while men on horseback were seen flinging themselves off, and drivers dismounting in all directions, making their escape up flights of steps and common stairs—mothers or nurses with broods of young children flying hither and thither in distraction, or standing on the very crown of the causeway, wringing their hands in despair. The wheel-barrows were easily disposed of—nor was there much greater difficulty with the gigs and shandrydans. But the hackney-coaches stood confoundedly in the way—and a wagon, drawn by four horses, and heaped up to the very sky with beer-barrels, like the Tower of Babel or Babylon, did indeed give us pause—but ere we had leisure to ruminate on the shortness of human life, we broke through between the leaders and the wheels with a crash of leathern breeching, dismounted collars, riven harness, and tumbling of enormous horses that was perilous to hear; when, as Sin and Satan would have it—would you believe it?—there, twenty kilts deep at the least, was the same accursed Highland regiment, the forty-second, with fixed bayonets, and all its pipers in the van, the pibroch yelling, squeaking, squealing, grunting, growling, roaring, as if it had only that very instant broken out—so, suddenly to the right—about went the bag-pipe-haunted mare, and away up the Mound, past the pictures of Irish Giants—Female Dwarfs—Albinos—an Elephant endorsed with towers—Tigers and Lions of all sorts—and a large wooden building, like a pyramid, in which there was the thundering of cannon—for the battle, we rather think, of Camperdown was going on—the Bank of Scotland seemed to sink into the NorLoch—one gleam through the window of the eyes of the Director-General—and to be sure how we did make the street-stalls of the Lawn-market spin! The man in St. Giles's steeple was playing his one o'clock tune on the bells, heedless in that elevation of our career—in less than no time John Knox, preaching from a house half-way down the Canongate, gave us the go-by—and down through one long wide sprawl of men, women, and children we wheeled past the Gothic front, and round the south angle of Holyrood, and across the King's-park, where wan and withered sporting debtors held up their hands and cried, Hurra—hurra—hurra—without stop or stay, up the rocky way that leads to St. Anthony's Well and Chapel—and now it was manifest that we were bound for the summit of Arthur's Seat. We hope that we were sufficiently thankful that a direction was not taken towards Salisbury Crags, where we should have been dashed into many million pieces. Free now from even the slightest suburban impediment, obstacle, or interruption, we began to eye our gradually rising situation in life—and looking over our shoulder, the sight of city and sea was indeed magnificent. There in the distance rose North Berwick Law—but though we have plenty of time now for description, we had scant time then for beholding perhaps the noblest scenery in Scotland. Up with us—up with us into the clouds—and just as St. Giles's bells ceased to jingle, and both girths broke, we crowned the summit, and sat on horseback like king Arthur himself, eight hundred feet above the level of the sea!

Blackwood's Magazine.Select Biography No. LVIII

LELAND

John Leland, the father of the English antiquaries, was born in London, about the end of the reign of Henry VII. He was a pupil to William Lily, the celebrated grammarian—the first head master of St. Paul's school; and by the kindness and liberality of a Mr. Myles, he was sent to Christ's college. Cambridge. From this university he removed to All Souls, Oxford, where he paid particular attention to the Greek language. He afterwards went to Paris, where he cultivated the acquaintance of the principal scholars of the age, and could probably number among his correspondents the illustrious names of Buddoeus, Erasmus, the Stephani, Faber, and Turnebus; in this city he perfected himself in the knowledge of the Latin and Greek tongues, to which he afterwards added that of several modern languages. On his return to England he took orders, and was appointed one of the chaplains to Henry VIII., who gave him the rectory of Popelay, in the marshes of Calais, appointed him his library keeper, and conferred on him the title of Royal Antiquary, which no other person in this kingdom, before, or after possessed. In this character his majesty in 1533 granted him a commission, empowering him to search after England's antiquities, and peruse the libraries of all cathedrals, abbeys, priories, colleges, &c., as also all the places wherein records, writings, and whatever else was lodged that related to antiquity. "Before Leland's time," says Hearne, in his preface to the Itinerary, "all the literary monuments of antiquity were totally disregarded; and the students of Germany apprised of this culpable indifference, were suffered to enter our libraries unmolested, and to cut out of the books deposited there whatever passages they thought proper, which they afterwards published as relics of the ancient literature of their own country."

In this research Leland was occupied above six years in travelling through England, and in visiting all the remains of ancient buildings and monuments of every kind. On its completion, he hastened to the metropolis, to lay at the feet of his sovereign the result of his labours, which he presented to Henry, under the title of a "New Year's Gift,"4 in which he says, "I have so traviled yn your dominions booth by the se costes and the midle partes, sparing nother labor nor costes, by the space of these vi. yeres paste, that there is almoste nother cape, nor bay, haven, creke or peers, river or confluence of rivers, breches, watchies, lakes, meres, fenny waters, montagnes, valleis, mores, hethes, forestes, chases wooddes, cities, burges, castelles, principale manor placis, monasteries, and colleges, but I have seene them; and notid yn so doing a hole worlde of thinges very memorable."

At the dissolution of the monasteries, Leland made application to Secretary Cromwell, to entreat his assistance in getting the MSS. they contained sent to the king's library. In 1542 Henry presented him with the valuable rectory of Hasely, in Oxfordshire; the year following he preferred him to a canonry of King's college, now Christchurch, Oxford, and about the same time collated him to a prebend in the church of Sarum. As his duties in the church did not require much active service, he retired with his collections to his house in London, where he sat about digesting them, and preparing the publication he had promised to the world; but either his intense application, or some other cause, brought upon him a total derangement of mind, and after lingering two years in this state, he died on the 18th of April, 1552.

The writings of Leland are numerous; in his lifetime he published several Latin and Greek poems, and some tracts on antiquarian subjects. His valuable and voluminous MSS., after passing through many hands, came into the Bodleian library, furnishing very valuable materials to Stow, Lambard, Camden, Burton, Dugdale, and many other antiquaries and historians. Polydore Virgil, who had stolen from them pretty freely, had the insolence to abuse Leland's memory—calling him "a vain glorious man." From these collections Hall published, in 1709, "Commentarii de Scriptoribus Brittanicis." "The Itinerary of John Leland, Antiquary," was published by the celebrated Hearne, at Oxford, in nine volumes, 8vo., 1710, of which a second edition was printed in 1745, with considerable improvements and additions. The same editor published "Joannis Lelandi Antiquarii de Rebus Brittanicis Collectanea." in six volumes, Oxon. 1716, 8vo.

BIOS.THE SELECTOR AND LITERARY NOTICES OF NEW WORKS

CORAL ISLANDS

[In a recent Number of the MIRROR we quoted from Mr. Montgomery's Pelican Island a beautiful description of the formation of coral reefs or rocks; and we are now induced to resume our extracts from this soul stirring poem, with the following description of the process by which these reefs or rocks become beautiful and picturesque islands. Mr. Montgomery's poetical talent is altogether of the highest order, or, to use a familiar phrase, his Pelican Island is "a gem of the first water." How exquisite is the following picture of creation!]

Here was the infancy of life, the ageOf gold in that green isle, itself new-born,And all upon it in the prime of being,Love, hope, and promise, 'twas in miniatureA world unsoil'd by sin; a ParadiseWhere Death had not yet enter'd; Bliss had newlyAlighted, and shut close his rainbow wings,To rest at ease, nor dread intruding ill.Plants of superior growth now sprang apace,With moon-like blossoms crown'd, or starry glories;Light flexible shrubs among the greenwood play'dFantastic freaks,—they crept, they climb'd, they budded,And hung their flowers and berries in the sun;As the breeze taught, they danced, they sung, they twinedTheir sprays in bowers, or spread the ground with net-work.Through the slow lapse of undivided time,Silently rising from their buried germs,Trees lifted to the skies their stately heads,Tufted with verdure, like depending plumage,O'er stems unknotted, waving to the wind:Of these in graceful form, and simple beauty,The fruitful cocoa and the fragrant palmExcell'd the wilding daughters of the wood,That stretch'd unwieldy their enormous arms,Clad with luxuriant foliage, from the trunk,Like the old eagle, feather'd to the heel;While every fibre, from the lowest rootTo the last leaf upon the topmost twig,Was held by common sympathy, diffusingThrough all the complex frame unconscious life.Such was the locust with its hydra boughs,A hundred heads on one stupendous trunk;And such the mangrove, which, at full-moon flood,Appear'd itself a wood upon the waters,But when the tide left bare its upright roots,A wood on piles suspended in the air;Such too the Indian fig, that built itselfInto a sylvan temple, arch'd aloofWith airy aisles and living colonnades,Where nations might have worshipp'd God in peace.From year to year their fruits ungather'd fell;Not lost, but quickening where they lay, they struckRoot downward, and brake forth on every hand,Till the strong saplings, rank and file, stood up,A mighty army, which o'erran the isle,And changed the wilderness into a forest.All this appear'd accomplish'd in the spaceBetween the morning and the evening star:So, in his third day's work, Jehovah spake,And Earth, an infant, naked as she cameOut of the womb of chaos, straight put onHer beautiful attire, and deck'd her robeOf verdure with ten thousand glorious flowers,Exhaling incense; crown'd her mountain-headsWith cedars, train'd her vines around their girdles,And pour'd spontaneous harvests at their feet.Nor were those woods without inhabitantsBesides the ephemera of earth and air;—Where glid the sunbeams through the latticed boughs,And fell like dew-drops on the spangled ground,To light the diamond-beetle on his way;—Where cheerful openings let the sky look downInto the very heart of solitude,On little garden-pots of social flowers,That crowded from the shades to peep at daylight;—Or where unpermeable foliage madeMidnight at noon, and chill, damp horror reign'dO'er dead, fall'n leaves and slimy funguses;—Reptiles were quicken'd into various birth.Loathsome, unsightly, swoln to obscene bulk,Lurk'd the dark toad beneath the infected turf;The slow-worm crawl'd, the light cameleon climb'd,And changed his colour as his pace he changed;The nimble lizard ran from bough to bough,Glancing through light, in shadow disappearing;The scorpion, many-eyed, with sting of fire,Bred there,—the legion-fiend of creeping things;Terribly beautiful, the serpent lay,Wreath'd like a coronet of gold and jewels,Fit for a tyrant's brow; anon he flewStraight as an arrow shot from his own rings,And struck his victim, shrieking ere it wentDown his strain'd throat, that open sepulchre.Amphibious monsters haunted the lagoon;The hippopotamus, amidst the flood,Flexile and active as the smallest swimmer;But on the bank, ill balanced and infirm,He grazed the herbage, with huge, head declined,Or lean'd to rest against some ancient tree.The crocodile, the dragon of the waters,In iron panoply, fell as the plague,And merciless as famine, cranch'd his prey,While, from his jaws, with dreadful fangs all serried,The life-blood dyed the waves with deadly streams.The seal and the sea-lion, from the gulfCame forth, and couching with their little ones.Slept on the shelving rocks that girt the shores,Securing prompt retreat from sudden danger;The pregnant turtle, stealing out at eve,With anxious eye, and trembling heart, exploredThe loneliest coves, and in the loose warm sandDeposited her eggs, which the sun hatch'd:Hence the young brood, that never knew a parent,Unburrow'd and by instinct sought the sea;Nature herself, with her own gentle hand,Dropping them one by one into the flood,And laughing to behold their antic joy,When launch'd in their maternal element.The vision of that brooding world went on;Millions of beings yet more admirableThan all that went before them now appear'd;Flocking from every point of heaven, and fillingEye, ear, and mind, with objects, sounds, emotionsAkin to livelier sympathy and loveThan reptiles, fishes, insects, could inspire;—Birds, the free tenants of land, air, and ocean,Their forms all symmetry, their motions grace;In plumage delicate and beautiful,Thick without burthen, close as fishes' scales,Or loose as full-blown poppies to the breeze;With wings that might have had a soul within them,They bore their owners by such sweet enchantment;—Birds, small and great, of endless shapes and colours,Here flew and perch'd, there swam and dived at pleasure;Watchful and agile, uttering voices wildAnd harsh, yet in accordance with the wavesUpon the beech, the winds in caverns moaning,Or winds and waves abroad upon the water.Some sought their food among the finny shoals,Swift darting from the clouds, emerging soonWith slender captives glittering in their beaks;These in recesses of steep crags constructedTheir eyries inaccessible, and train'dTheir hardy broods to forage in all weathers;Others, more gorgeously apparell'd, dweltAmong the woods, on Nature's dainties feeding,Herbs, seeds, and roots; or, ever on the wing,Pursuing insects through the boundless air:In hollow trees or thickets these conceal'dTheir exquisitely woven nests; where layTheir callow offspring, quiet as the downOn their own breasts, till from her search the damWith laden bill return'd, and shared the mealAmong the clamorous suppliants, all agape;Then, cowering o'er them with expanded wings,She felt how sweet it is to be a mother.Of these, a few, with melody untaught,Turn'd all the air to music within hearing,Themselves unseen; while bolder quiristersOn loftier branches strain'd their clarion-pipes,And made the forest echo to their screamsDiscordant,—yet there was no discord there,But temper'd harmony: all tones combining,In the rich confluence often thousand tongues,To tell of joy and to inspire it. WhoCould hear such concert, and not join in chorus?Not I;—sometimes entranced, I seem'd to floatUpon a buoyant sea of sounds: againWith curious ear I tried to disentangleThe maze of voices, and with eye as niceTo single out each minstrel, and pursueHis little song through all its labyrinth,Till my soul enter'd into him, and feltEvery vibration of his thrilling throat,Pulse of his heart, and flutter of his pinions.Often, as one among the multitude,I sang from very fulness of delight;Now like a winged fisher of the sea,Now a recluse among the woods,—enjoyingThe bliss of all at once, or each in turn.RAPIDS OF NIAGARA

The Rapids begin about half a mile above the cataract; and although the breadth of the river might at first make them appear of little importance, a nearer inspection will convince the stranger of their actual size, and the terrific danger of the passage. The inhabitants of the neighbourhood regard it as certain death to get once involved in them; and that, not merely because all escape from the cataract would be hopeless, but because the violent force of the water among the rocks in the channel, would instantly dash the bones of a man in pieces. Instances are on record of persons being carried down by the stream; indeed there was an instance of two men carried over in March last; but no one is known to have ever survived. Indeed, it is very rare that the bodies are found; as the depth of the gulf below the cataract, and the tumultuous agitation of the eddies, whirlpools, and counter currents, render it difficult for any thing once sunk to rise again; while the general course of the water is so rapid, that it is soon hurried far down the stream. The large logs which are brought down in great numbers during the spring, bear sufficient testimony to these remarks. Wild ducks, geese, &c. are frequently precipitated over the cataract, and generally re-appear either dead, or with their legs or wings broken. Some say that water-fowl avoid the place when able to escape, but that the ice on the shores of the river above often prevents them from obtaining food, and that they are carried down from mere inability to fly; while others assert that, they are sometimes seen voluntarily riding among the rapids, and, after descending half-way down the cataract, taking wing, and returning to repeat their dangerous amusement.—American Work.

BRIDAL, CANZONET

Sir Knight, heed not the clarion's call,From hill, or from valley, or turretted hall;Cease, holy Friar, cease for awhileThe anthem that swells through the fretted aisle;Forester bold, to the bugle's soundListen no longer, though gaily wound,But haste to the bridal, haste away,Where love's rebeck is tuned to a sweeter lay.Sir Knight, Sir Knight, no longer twineThe laurel-leaf o'er that bold brow of thine;Friar, to-day from thy temples tearThe ivy garland that sages wear;To-day, bold Forester, cast asideThy oak-leaf crown, the woodland's pride,And bind round your brows the myrtle gay,While the rebeck resounds love's sweetest lays.Sir Knight, urge not now the gallant steedO'er the plains that to honour and glory lead;Friar, forget thy order's vow,And pace not the gloomy cloisters now.Chase no longer with bow and with spear,Forester bold, the dappled deer,But tread me a measure as light and gayAs ever kept lime to the rebeck's lay.Neele's Romance of History.THE GATHERER

"I am but a Gatherer and disposer of other men's stuff."—Walton.

TRAVELLING

Sterne pitied the man who could travel from Dan to Beersheba, and say all "was barren:" however delighted travellers or tourists may be on their journey, it is surprising how few details are preserved in their memory. This occasioned Dr. Johnson to remark, in his "Tour to the Hebrides," how much the lapse even "of a few hours takes from the certainty of knowledge, and the distinctness of imagery;" and that "those who trust to memory what cannot be safely trusted but to the eye, must tell by guess, what a few hours before they had known with certainty." We were never more convinced of the importance of these observations than after our first visit to the dock-yard, at Portsmouth. In collating some little memoranda made on the spot, we referred to our party, (seven in number) on our return to the inn, for the extent of the dock-yard: not one of them could give a correct answer, though all had just heard it detailed and explained with accuracy. Dr. Kitchener may well recommend tourists to walk about with note-books in their hands! and such inadvertence as the preceding almost warrants the oddity of his suggestion.

MOTTOES FOR DECANTER LABELS

Arridet PORTus? subeat non causa doloris.

SumebatiS HERI? non dolor est hodie.

Hic liquor est molLIS BONus, aptus ad omnia laeta.

Oppida ne CALCA VALLAta ad praelia, quoerens, Sisonitum capias ecce tibi est Volupe.

Dum lucet CLARE Te magis iste trahat.

Literary Gazette.MALARIA

Dr. Gregory, father of the late celebrated professor in Edinburgh, when a student in a part of Germany where malaria prevailed, from being a philosopher and living low, drinking only water, was seized with intermittent fever, when his jolly companions, who ate and drank freely, escaped. If brandy or other stimulants are taken previous to exposure to malaria, intermittent fever is generally prevented. Such are the opinions of the doctor, and if Dr. Macculloch be right, we suggest the establishment of a brandy vault at each angle of the parks, that every passenger may prepare himself.

LORD HOWE

When the late Lord Howe was a captain, a lieutenant, not remarkable for courage or presence of mind in dangers (common fame had brought some imputation upon his character) ran to the great cabin and informed his commander that the ship was on fire near the gun-room. Soon after this he returned exclaiming, "You need not be afraid as the fire is extinguished." "Afraid!" replied Captain H. a little nettled, "how does a man feel, Sir, when he is afraid? I need not ask how he looks."

BACKGAMMON BOARDS

We frequently find backgammon boards with backs lettered as if they were two folio volumes. The origin of it was thus; Eudes, bishop of Sully, forbade his clergy to play at chess. As they were resolved not to obey the commandment, and yet dared not have a chess-board seen in their houses or cloisters, they had them bound and lettered as books, and played at night, before they went to bed, instead of reading the New Testament or the Lives of the Saints; and the monks called the draft or chess-board their wooden gospels. They had also drinking vessels bound to resemble the breviary, and were found drinking, when it was supposed they were at prayer.—Literary Gazette.

LOVE OF THE COUNTRY

Country people will tell you that they like the country, and detest the town, although their enjoyments are of a kind which may be obtained in far greater perfection in the latter than in the former. The only person I ever knew who was honest in this respect, was a gentleman, the possessor of a beautiful seat, in a beautiful country, when he avowed his opinion, that there was "no garden like Covent-garden, and no flower like a cauliflower."

C.L.The Morning Chronicle, Nov. 20, in noticing the funeral of the late Mr. Sale, says, "At a little after three o'clock, the body of the lamented gentleman entered the church."

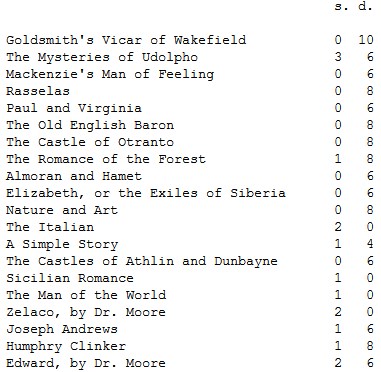

LIMBIRD'S EDITION OF THE BRITISH NOVELIST, Publishing in Monthly Parts, price 6d. each.—Each Novel will be complete in itself, and may be purchased separately.

The following Novels are already Published:

Published by J. LIMBIRD, 143, Strand, London, and Sold by all Booksellers and Newsmen.

1

See MIRROR, vol 3, p 194—vol 5. p 311.

2

We requote this passage from Mr. M'Creery, as it has already appeared in vol. 5; and in vol. 3, a correspondent denies that the first English book was printed at Westminster; but we are disposed to think that an impartial examination of the testimonies on each side of the controversy will decide in favour of Caxton.

3

We did not know that such unpleasantries as Chancery injunctions were part of African law; perhaps sand may not be removed from the desert "without leave of the trustees," like scrapings from our roads.

4

This was published by Bale in 1549, 8vo.