полная версия

полная версияThe Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 10, No. 286, December 8, 1827

The Sketch Book. No. LI

THE PHANTOM HAND

I see a hand you cannot see,Which beckons me away!In a lonely part of the bleak and rocky coast of Scotland, there dwelt a being, who was designated by the few who knew and feared him, the Warlock Fisher. He was, in truth, a singular and a fearful old man. For years he had followed his dangerous occupation alone; adventuring forth in weather which appalled the stoutest of the stout hearts that occasionally exchanged a word with him, in passing to and fro in their mutual employment. Of his name, birth, or descent, nothing was known; but the fecundity of conjecture had supplied an unfailing stock of materiel on these points. Some said he was the devil incarnate; others said he was a Dutchman, or some other "far-away foreigner," who had fled to these comparative solitudes for shelter, from the retribution due to some grievous crime; and all agreed, that he was neither a Scot nor a true man. In outward form, however, he was still "a model of a man," tall, and well-made; though in years, his natural strength was far from being abated. His matted black hair, hanging in elf-locks about his ears and shoulders, together with the perpetual sullenness which seemed native in the expression of features neither regular nor pleasing, gave him an appearance unendurably disgusting. He lived alone, in a hovel of his own construction, partially scooped out of a rock—was never known to have suffered a visitor within its walls—to have spoken a kind word, or done a kind action. Once, indeed, he performed an act which, in a less ominous being, would have been lauded as the extreme of heroism. In a dreadfully stormy morning, a fishing-boat was seen in great distress, making for the shore—there were a father and two sons in it. The danger became imminent, as they neared the rocky promontory of the fisher—and the boat upset. Women and boys were screaming and gesticulating from the beach, in all the wild and useless energy of despair, but assistance was nowhere to be seen. The father and one of the lads disappeared for ever; but the younger boy clung, with extraordinary resolution, to the inverted vessel. By accident, the Warlock Fisher came to the door of his hovel, saw the drowning lad, and plunged instantaneously into the sea. For some minutes he was invisible amid the angry turmoil; but he swam like an inhabitant of that fearful element, and bore the boy in safety to the beach. From fatigue or fear, or the effects of both united, the poor lad died shortly afterwards; and his grateful relatives industriously insisted, that he had been blighted in the grasp of his unhallowed rescuer!

Towards the end of autumn, the weather frequently becomes so broken and stormy in these parts, as to render the sustenance derived from fishing extremely precarious. Against this, however, the Warlock Fisher was provided; for, caring little for weather, and apparently less for life, he went out in all seasons, and was known to be absent for days, during the most violent storms, when every hope of seeing him again was lost. Still nothing harmed him: he came drifting back again, the same wayward, unfearing, unhallowed animal. To account for this, it was understood that he was in connexion with smugglers; that his days of absence were spent in their service—in reconnoitring for their safety, and assisting their predations. Whatever of truth there might be in this, it was well known that the Warlock Fisher never wanted ardent spirits; and so free was he in their use and of tobacco, that he has been heard, in a long and dreary winter's evening, carolling songs in a strange tongue, with all the fervour of an inspired bacchanal. It has been said, too, at such times he held strange talk with some who never answered, deprecated sights which no one else could see, and exhibited the fury of an outrageous maniac.

It was towards the close of an autumn day, that a tall young man was seen surveying the barren rocks, and apparently deserted shores, near the dwelling of the fisher. He wore the inquiring aspect of a stranger, and yet his step indicated a previous acquaintance with the scene. The sun was flinging his boldest radiance on the rolling ocean, as the youth ascended the rugged path which led to the Warlock Fisher's hut. He surveyed the door for a moment, as if to be certain of the spot; and then, with one stroke of his foot, dashed the door inwards. It was damp and tenantless. The stranger set down his bundle, kindled a fire, and remained in quiet possession. In a few hours the fisher returned. He started involuntarily at the sight of the intruder, who sprang to his feet, ready for any alternative.

"What seek you in my hut?" said the Fisher.

"A shelter for the night—the hawks are out."

"Who directed you to me?"

"Old acquaintance!"

"Never saw you with my eyes—shiver me! But never mind, you look like the breed—a ready hand and a light heel, ha! All's right—tap your keg!"

No sooner said than done. The keg was broached, and a good brown basin of double hollands was brimming at the lips of the Warlock Fisher. The stranger did himself a similar service, and they grew friendly. The fisher could not avoid placing his hand before his eyes once or twice, as if wishful to avoid the keen gaze of the stranger, who still plied the fire with fuel and his host with hollands. Reserve was at length annihilated, and the fisher jocularly said—

"Well, and so we're old acquaintance, ha?"

"Ay," said the young man, with another searching glance. "I was in doubt at first, but now I'm certain."

"And what's to be done?" said the Fisher.

"An hour after midnight you must put me on board –'s boat, she'll be abroad. They'll run a light to the masthead, for which you'll steer. You're a good hand at the helm in a dark night and a rough sea," was the reply.

"How, if I will not?"

"Then—your life or mine!"

They sprang to their feet simultaneously, and an immediate encounter seemed inevitable.

"Psha!" said the Fisher, sinking on his seat, "what madness this is! I was a thought warm with the liquor, and the recollections of past times were rising on my memory. Think nothing of it. I heard those words once before," and he ground his teeth in rage—"Yes, once—but in a shriller voice than your's! Sometimes, too, the bastard rises to my view; and then I smite him so—bah! give us another basin-full!" He stuck short at vacancy, snatched the beverage from the stranger, and drank it off. "An hour after midnight, said ye?"

"Ay—you'll see no bastards then!"

"Worse—may be—worse!" muttered the Fisher, sinking into abstraction, and glaring wildly on the flickering embers before him.

"Why, how's this?" said the stranger. "Are your senses playing bo-peep with the ghost of some pigeon-livered coast captain, eh? Come, take another pull at the keg, to clear your head-lights, and tell us a bit of your ditty."

The Fisher took another draught, and proceeded—

"About five-and-twenty years ago, a stranger came to this hut—may the curse of God annihilate him!—"

"Amen to that," said the young man.

"He brought with him a boy and a girl, a purse of gold, and – the arch fiend's tongue, to tempt me! Well, it was to take these children out to sea—upset the boat—and lose them!"—

"And you did so!" interrupted the stranger.

"I tried—but listen. On a fine evening, I took them out: the sun sunk rapidly, and I knew by the freshening of the breeze, there would be a storm. I was not mistaken. It came on even faster than I wished. The children were alarmed—the boy, in particular, grew suspicious; he insisted that I had an object in going out so far at sun-set. This irritated me,—and I rose to smite him, when the fair girl interposed her fragile form between us. She screamed for mercy, and clung to my arm with the desperation of despair. I could not shake her off! The boy had the spirit of a man; he seized a piece of spar, and struck me on the temples. 'How, you villain!' said he, 'your life or mine!' At that moment the boat upset, and we were all adrift. The boy I never saw again—a tremendous sea broke between us—but the wretched girl clung to me like hate! Damnation!—her dying scream is ringing in my ears like madness! I struck her on the forehead, and she sank—all but her hand, one little, white hand would not sink! I threw myself on my back, and struck at it with both my feet—and then I thought it sunk for ever. I made the shore with difficulty, for I was stunned and senseless, and the ocean heaved as if it would have washed away the mortal world—and the lightnings blazed as if all hell had come to light the scene of warfare! I have never since been on the sea at midnight, but that hand has followed or preceded me; I have never –." Here he sank down from his seat, and rolled himself in agony upon the floor.

"Poor wretch!" muttered the stranger, "what hinders now my long-sought vengeance? Even with my foot—but thou shalt share my murdered sister's grave!"

"A shot is fired—look out for the light!" said the young man.

The Fisher went to the door; but suddenly started back, clasping his hands before his face.

"Fire and brimstone! there it is again!" he cried.

"What?" said his companion, looking cooly round him.

"That infernal hand! Lightnings blast it!—but that's impossible," he added, in a fearful under-tone, which sounded as if some of the eternal rocks around him were adding a response to his imprecations—"that's impossible! It is a part of them—it has been so for years—darkness could not shroud it—distance could not separate it from my burning eye-balls!—awake, it was there—asleep, it flickered and blazed before me!—it has been my rock a-head through life, and it will herald me to hell!" So saying, he pressed his sinewy hands upon his face, and buried his head between his knees, till the rock beneath him seemed to shake with his uncontrollable agony.

"Again it beckons me!" said he, starting up—"ten thousand fires are blazing in my heart—in my brain!—where, where can I be worse? Fiend, I defy thee!"

"I see nothing," said his companion, with unalterable composure.

"You see nothing!" thundered the Fisher, with mingling sarcasm and fury—"look there." He snatched his hand, and pointing steadily into the gloom, again murmured, "Look there! look there!"

At that moment the lightning blazed around with appalling brilliancy; and the stranger saw a small white hand, pointing tremulously upwards.

"I saw it there," said he, "but it is not hers! Infatuated, abandoned villain." he continued, with irrepressible energy, "it is not my sister's hand—no! it is the incarnate fiend's who tempted you, and who now waves you to perdition—begone together!"

He aimed a dreadful blow at the astonished Fisher, who instinctively avoided the stroke. Mutually wound up to the highest pitch of anger, they grappled each the other's throat, set their feet, and strained for the throw, which was inevitably to bury both in the wild waves beneath. A faint shriek was heard, and a gibbering, as of many voices, came fluttering around them.

"Chatter on!" said the Fisher, "he joins you now!"

"Together—it will be together!" said the stranger, as with a last desperate effort he bent his adversary backward from the betling cliff. The voice of the Fisher sounded hoarsely in execration, as they dashed into the sea together; but what he said was drowned in the hoarser murmur of the uplashing surge! The body of the stranger was found on the next morning, flung far up on the rocky shore—but that of the murderer was gone for ever!

The superstitious peasantry of the neighbourhood still consider the spot as haunted; and at midnight, when the waves dash fitfully against the perilous crags, and the bleak winds sweep with long and angry moan around them, they still hear the gibbering voices of the fiends, and the mortal execrations of the Warlock Fisher!—but, after that fearful night, no man ever saw THE PHANTOM HAND!—Literary Magnet.

ARCANA OF SCIENCE

ElephantsAll the elephants which were exported from Point de Galle were caught in ancient, as well as in modern times, in that tract of country which extends from Matura to Tangcolle, in the south of Ceylon, and which, from its being famous for its elephants in his days, is described by Ptolemy in the map he made of Ceylon sixteen hundred years ago as the elephantum pascua. The trade in elephants from Ceylon, which used to be lucrative, is now completely annihilated, in consequence of all the petty Rajahs, Foligars, and other chiefs in the southern peninsula of India, who used formerly to purchase Ceylon elephants as a part of their state, having lost their sovereignties, and being therefore no longer required to keep up any state of this description. A gentleman who has a plantation at Candy, it is understood, recently introduced the use of elephants, in ploughing, with great advantage.—Trans. Asiatic Society.

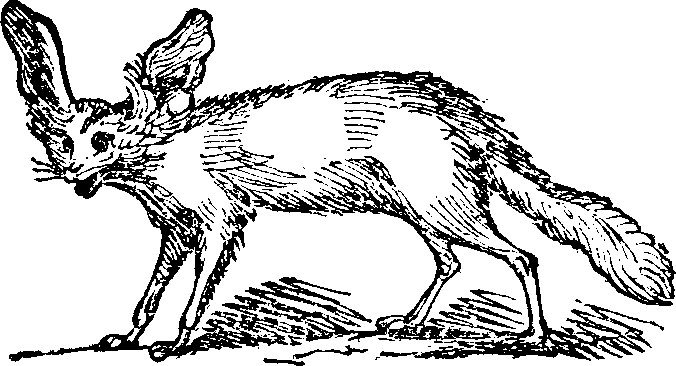

The Fennecous Cerdo

This beautiful and extraordinary animal, or at least one of its genus, was first made known to European naturalists by Bruce, who received it from his dragoman, whilst consul general at Algiers. It is frequently met with in the date territories of Africa, where the animals are hunted for their skins, which are afterwards sold at Mecca, and then exported to India. Bruce kept his animal alive for several months, and took a drawing of it in water colours, of the natural size, a copy of which, on transparent paper, was clandestinely made by his servant. Mr. Brander, into whose hands the Fennecus fell after Bruce left Algiers, gave an account of it in "Some Swedish Transactions," but refused to let the figure be published, the drawing having been unfairly obtained.3 Bruce asserts that this animal is described in many Arabian books, under the name of El Fennec, which appellation he conceives to be derived from the Greek word for a palm or date-tree.

The favourite food of Bruce's Fennec was dates or any sweet fruit; but it was also very fond of eggs; when hungry it would eat bread, especially with honey or sugar. His attention was immediately attracted if a bird flew near him, and he would watch it with an eagerness that could hardly be diverted from its object; but he was dreadfully afraid of a cat. Bruce never heard that he had any voice. During the day he was inclined to sleep, but became restless and exceedingly unquiet as night came on. The above Fennec was about ten inches long, the tail five inches and a quarter, near an inch of it on the tip, black. The colour of the body was dirty white, bordering on cream colour; the hair on the belly rather whiter, softer and longer than on the rest of the body. His look was sly and wily; he built his nest on trees, and did not burrow in the earth.

Naturalists, especially those of France, were long induced to suspect the truth of Bruce's description of this animal; but a specimen from the interior of Nubia, and preserved in the museum at Frankfort, has recently been engraved; and thus the matter nearly settled by the animal belonging to the genus Canis, and the sub genus Vulpes; the number of teeth and form, being precisely the same as the fox, which it also resembles in its feet, number of toes, and form of tail.

For the above engraving we are indebted to the Appendix to the important and interesting Travels of Messrs. Denham and Clapperton. It is therein described as generally of a white colour, inclining to straw yellow; above, from the occiput to the insertion of the tail it is light rufous brown, delicately pencilled with fine black lines, from thinly scattered hairs tipped with black; the exterior of the thighs is lighter rufous brown; the chin, throat, belly, and interior of the thighs and legs are white, or cream colour. The nose is pointed, and black at the extremity; above, it is covered with very short, whitish hair inclining to rufous, with a small irregular rufous spot on each side beneath the eyes; the whiskers are black, rather short and scanty; the back of the head is pale rufous brown. The ears are very large, erect, and pointed, and covered externally with short, pale, rufous brown hair; internally, they are thickly fringed on the margin with long grayish white hairs, especially in front; the rest of the ears, internally, is bare; externally, they are folded or plaited at the base. The tail is very full, cylindrical, of a rufous brown colour, and pencilled with fine black lines like the back. The fur is very soft and fine; that on the back, from the back to the insertion of the tail, as well as that on the upper part of the shoulder before, and nearly the whole of the hinder thigh, is formed of tri-coloured hairs, the base of which is of a dark lead colour, the middle white, and the extremity light rufous brown.

Fossil TurtleA beautiful and perfect fossil of the sea turtle has recently been discovered in an extensive stratum of limestone, four fathoms water, called the Stone Ridge, about four miles off Harwich harbour. It is incrusted in a mass of ferruginous limestone, and weighs 180 lbs.

ApplesA gentleman of Staffordshire recommends the preservation of apples for winter store, packed in banks or hods of earth like potatoes.—Communication to the Horticultural Society.

Uses of SealsThe benefits which the inhabitants of frigid regions derive from seals, are far too numerous and diversified to be particularized, as they supply them with almost all the conveniences of life. We, on the contrary, so persecute this animal, as to destroy hundreds of thousands annually, for the sake of the pure and transparent oil with which the seal abounds; 2ndly, for its tanned skin, which is appropriated to various purposes by different modes of preparation; and thirdly, we pursue it for its close and dense attire. In the common seal, the hair of the adult is of one uniform kind, so thickly arranged and imbued with oil, as to effectually resist the action of water; while, on the contrary, in the antarctic seals the hair is of two kinds: the longest, like that of the northern seals; the other, a delicate, soft fur, growing between the roots of the former, close to the surface of the skin, and not seen externally; and this beautiful fur constitutes an article of very increasing importance in commerce; but not only does the clothing of the seal vary materially in colour, fineness, and commercial situation, in the different species, but not less so in the age of the animal. The young of most kinds are usually of a very light colour, or entirely white, and are altogether destitute of true hair, having this substituted by a long and particularly soft fur.—Quarterly Journal.

Method of cutting GlassIf a tube, or goblet, or other round glass body is to be cut, a line is to be marked with a gun flint having a sharp angle, an agate, a diamond, or a file, exactly on the place where it is to be cut. A long thread covered with sulphur is then to be passed two or three times round the circular line, and to be inflamed and burnt; when the glass is well heated some drops of cold water are to be thrown on it, when the piece will separate in an exact manner, as if cut with scissors. It is by this means that glasses are cut circularly into thin bands, which may either be separated from, or repose upon each other, at pleasure, in the manner of a spring–From the French.

Preservation of SkinsA tanner at Tyman, in Hungary, uses with great advantage the pyroligueous acid, in preserving skins from putrefaction, and in recovering them when attacked. They are deprived of none of their useful qualities if covered by means of a brush with the acid, which they absorb very readily.—Quarterly Journal.

Organic Remains in SussexA short time since, the entire skeleton of a stag, of very large size, was dug up by some labourers, in excavating the bed of the river Ouse, near Lewes, in Sussex. The remains were found imbedded in a layer of sand, beneath the alluvial blue clay, forming the surface of the valley. The horns were in the highest state of preservation, and had seven points, like the American deer. The greater part of the skeleton was destroyed by the carelessness of the workmen; but a portion, including the horns, has been preserved in the collection of Mr. Mantell, near Lewes.

Stupendous LizardMr. Bullock, in his Travels, (just published) relates that he saw near New Orleans, "what are believed to be the remains of a stupendous crocodile, and which are likely to prove so, intimating the former existence of a lizard at least 150 feet long; for I measured the right side of the under jaw, which I found to be 21 feet along the curve; and 4 feet 6 inches wide: the others consisted of numerous vertebrae, ribs, femoral bones, and toes, all corresponding in size to the jaw; there were also some teeth: these, however, were not of proportionate magnitude. These remains were discovered, a short time since, in the swamp, near Fort Philip; and the other parts of the mighty skeleton, are, it is said, in the same part of the swamp."

Digby's PhilosophySir Kenelm Digby was a mere quack; but he was the son of an earl, and related to many noble families. His book on the supposed sympathetic powder, which cured wounds at any distance from the sufferer, is the standard of his abilities. This powder was Roman vitriol pounded. From this wild work, we, however learn, that the English routine of agriculture in his time was—1st. year, barley; 2nd. wheat; 3rd. beans; 4th. fallow.—Pinkerton.

CriticsThought, comprising its enumerated constituents and detailed process, is the most perfect and exalted elaboration of the human mind, and when protracted is a painful exertion; indeed, the greater portion of our species reluctantly submit to the toil and lassitude of reflection; but from laziness, or incapacity, and perhaps in some instances from diffidence, they suffer themselves to be directed by the opinions of others. Hence has arisen the swarm of critics and reviewers, those clouds that obscure the fair light that would beam on the mind of man, by his individual reflection, and through his existence degrade him, by a submission to assumed authority;—a voluntary blindness, that excludes him from the observation of nature, and through indolence and credulity render his noblest faculties feeble, assenting, and lethargic; and delude him to barter the inheritance of his intellect for a mess of pottage.—Dr. Haslam.—Lancet.

SPIRIT OF THE PUBLIC JOURNALS

MUNCHAUSEN RIDE THROUGH EDINBURGH

We were sitting rather negligently on an infernal animal, which, up to that day, had seemed quiet as a lamb—kissing our hand to Mrs. Davison, then Miss Duncan, and in the blaze of her fame, when a Highland regiment, no doubt the forty-second, that had been trudging down the Mound, so silently that we never heard them, all at once, and without the slightest warning, burst out, with all their bag-pipes, into one pibroch! The mare—to do her justice—had been bred in England, and ridden, as a charger, by an adjutant to an English regiment. She was even fond of music—and delighted to prance behind the band—unterrified by cymbals or great drum. She never moved in a roar of artillery at reviews—and, had the Castle of Edinburgh—Lord bless it—been self-involved, at that moment, in a storm of thunder and lightning, round its entire circle of cannon, that mare would not so much as have pricked up her ears, whisked her tail, or lifted a hoof. But the pibroch was more than horse-flesh and blood could endure—and off we two went like a whirlwind. Where we went—that is to say, what were the names of the few first streets along which we were borne, is a question which, as a man of veracity, we must positively decline answering. For some short space of time, lines of houses reeled by without a single face at the windows—and these, we have since conjectured, might be North and South Hanover street, and Queen-street. By and by we surely were in something like a square—could it be Charlotte-square?—and round and round it we flew—three, four, five, or six times, as horsemen do at the Caledonian amphitheatre—for the animal had got blind with terror, and kept viciously reasoning in a circle. What a show of faces at all the windows then! A shriek still accompanied us as we clattered, and thundered, and lightened along; and, unless our ears lied, there were occasional fits of stifled laughter, and once or twice a guffaw; for there was now a ringing of lost stirrups—and much holding of the mane. One complete round was executed by us, first on the shoulder beyond the pommel; secondly, on the neck; thirdly, between the ears; fourthly, between the forelegs, in a place called the counter, with our arms round the jugular veins of the flying phenomenon, and our toes in the air. That was, indeed, the crisis of our fever, but we made a wonderful recovery back into the saddle—righting like a boat capsized in a sudden squall at sea—and once more, with accelerated speed, away past the pillared front of St. George's church!