полная версия

полная версияThe Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 19, No. 552, June 16, 1832

(Shakspeare.) "I rejoice to think that the world is yet to have a greater man than your lordship, since the arch must fall at last."

Several of Shakspeare's least amusing plays are supposed to be not of his composition, such as Henry VI., and Troilus and Cressida, with the exception of the master-touches and some of the finer speeches, which probably were introduced by him. This, however, is a trick of trade in every department of science; and when we see, for instance, the collected works of some great artist, it would be ridiculous to suppose that his whole lifetime could have sufficed for so much handicraft, and perhaps in reality, only the faces and more delicate parts were the work of his pencil.

To return to Shakspeare. The objections to his style, which are many, especially to a more modern reader, are excusable from several causes. The writers of the Elizabethan age and previously, were all of them very coarse in their mode of expression, and the dramatists not very delicate in their plots, though in doing so they did but obey the dictates of fashion and the bad taste of the times. Even prolixity and circumlocution were countenanced, and the insufferable conceits we meet with in the poems of Donne, Cowley, and others, were highly relished in those days. Euphaeism (mentioned so often by Sir W. Scott in The Abbot,) was also then in vogue, and all these various peculiarities of style, language, &c. were indispensable in all that was offered to the public. Shakspeare's fondness and propensity for punning may claim the same excuse, viz. "the hoary head and furrowed face of custom;" yet there are some of these puns interspersed through his works, which are sad blots indeed to our modern fastidious eyes, and that we could well wish to see expunged; such a one now is this:

"Say, 'pardon,' king, let pity teach thee now.""Speak it in French, king, say, 'pardonnez moi.'""A quibble (says Dr. Johnson,) gave him such delight that he was content to purchase it by the sacrifice of reason, of propriety, and even of truth; a quibble was to him the fatal Cleopatra for which he lost the world, and was content to lose it!"

Schiller, who is styled "the Shakspeare of Germany," and who is so ardently admired at the present day, has indeed taken our author for his model; he has in many respects been too servile a student, for his plagiarisms are both close and numerous. Thus, any one acquainted with his celebrated play of The Robbers, will readily recollect that the whole story is built upon the secondary plot in King Lear, between the Duke of Gloucester and his two sons; one of these who is a natural child, and a villain withal, contrives to poison the mind of the father, and to eject the legitimate son from his favour; it will be found exactly thus in Schiller's famous story of "The Robbers." It must be acknowledged, however, that foreigners in general have never idolized Shakspeare, or paid him that devoted adoration, which his countrymen both pay and think him entitled to. Hear Voltaire's overdrawn and even paltry criticism of Hamlet. "The tragedy of Hamlet is a gross and barbarous composition, which would not be supported by the lowest populace in France and Italy. Hamlet goes mad in the second act, Ophelia in the third; he takes the father of his mistress for a rat, and runs him through the body. In despair, the heroine drowns herself. Her grave is dug on the stage, while the grave-diggers enter into a conversation suitable (!) to such low wretches, and play, as it were, with dead men's bones! Hamlet answers their abominable stuff, with follies equally disgusting. Hamlet, with his father and mother-in-law, drink together upon the stage; they sing at table, afterwards they quarrel, and battle and death ensue. In short, one might take this performance for the fruits of the imagination of a drunken savage." (Letters on the English Nation.)

In another place, this writer says, "Shakspeare had not a single spark of good taste, or knew one rule of the drama. In one of his monstrous farces, to which he has given the name of Tragedies, we find the jokes of the Roman shoemakers and cobblers introduced in the same scene with the orations of Brutus and Antony." (See Voltaire's Essays on Tragedy and Comedy.) Here this rival dramatist again objects to any introduction of the lower orders on the stage, and seems averse to whatever is natural, and to depicting life as it is; but if any excuse is necessary for Shakspeare on this head, we must remember that the stage was in his time, and indeed is now perhaps, more particularly levelled to please the populace, and its success more immediately depends on the common suffrage; accordingly the scenes of our English drama, and Shakspeare's scenes particularly, are very often laid among tradesmen and mechanics, and though it may be contrary to all good taste, the author is compelled to indulge in bombast expressions, pompous and thundering rhymes, and sometimes even ribaldry and mean, unmannerly buffoonery.

During his lifetime, Shakspeare acquired reputation principally through his poems, which from some unaccountable cause, are now comparatively neglected, and we may add unfortunately so for the enjoyment of the public. These poems were more admired than his plays, and what speaks higher in their favour, they are more expressively alluded to by contemporary writers. The "Venus and Adonis" is a splendid piece of composition, and very touching in its sentiment; even its illustrious author was proud to call it "the first heir of his invention." We have from it one of our most popular songs, which constitutes one of its stanzas:

"Bid me discourse, I will enchant thine ear,Or like a fairy, trip upon the green,Or like a nymph with long dishevell'd hairDance on the sands, and yet no footing seen."His ready talent for composition was singular, and perhaps unparalleled; his mind and hand ever went together, and it is reported he was never known to blot a line. He was an actor occasionally in his own plays, but it does not indeed appear that he excelled in this art.

Shakspeare never considered his works worthy of posterity, and was little careful of popularity while he lived; having acquired a competency by his labours, he retired to Stratford, and spent the remainder of his life in ease and retirement, like a private gentleman. His income was estimated at £200. The epitaph—not that on his monument, but on the rude stone actually covering his remains is to the following effect, and thus curiously written:

"Good friend, for Jesus SAKE forbeareTo digg T—E dust EncloAsed HERE TBlese be T—E man spares TEs stones T yAnd curst be hey moves my bones."I conclude this rather desultory article with Lord Lyttleton's splendid eulogy on him, which in a few words expresses more than the finest Philippic to his memory—"If all human things were to perish except the works of Shakspeare, it might still be known from them what sort of a creature Man was!"

F.

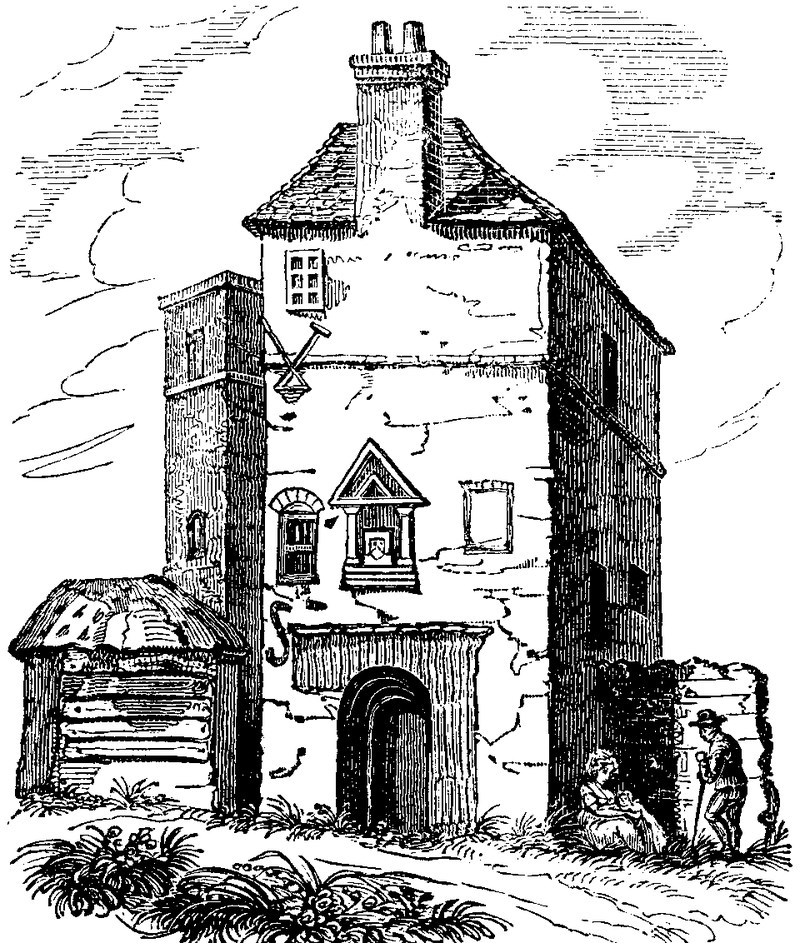

SIR THOMAS FOWLER'S LODGE, ISLINGTON

Few parishes in the environs of London are so rich in architectural antiquities as the "considerable village" of Islington. Canonbury-house, of which a solitary tower remains, is said to have been the country-residence of the Priors of St. Bartholomew, and to have been rebuilt early in the 16th century. Highbury belonged also to the Priory. The existing relics are chiefly of the Elizabethan age. The lodge, represented in the cut, belonged to an old mansion; the property of the Fowler family, built in 1595, which appears on a ceiling. The house fronts Cross-street, and the lodge is at the extremity of the garden, and adjoins Canonbury Fields. It is most probable that this was built as a summer-house by Sir Thomas Fowler, the younger, whose arms are placed in the wall, with the date 1655. It has been absurdly called Queen Elizabeth's Lodge, but with no other foundation than her majesty having passed through it when on a visit to Sir Thomas Fowler.

The Fowlers appear to have been of some note. Sir Thomas Fowler, the elder, who died in 1624, was one of the jury on Sir Walter Raleigh's trial: his son, Sir Thomas, was created a baronet in 1628; the title became extinct at his death. Some coats of arms were taken out of the windows of the old mansion. Among these were the arms of Fowler and Heron. Thomas Fowler, the first of the family who settled at Islington married the daughter of Herne, or Heron, of that place.5

The Pied Bull, near Islington Church, is stated to have been the residence of Sir Walter Raleigh; though Oldys, in his Life of Raleigh, says there is no proof of it; and John Shirley, of Islington, another of Raleigh's biographers, records nothing of his living there. The statement is, however, renewed in a Life of Sir Walter, published in 1740.

FINE ARTS

THE PANORAMA OF MILAN

By the aid of Mr. Burford's panoramic pencil, the sight-hunter of our times may enjoy a kind of imaginary tour through the world. At one season he wafts us to the balmy climes of India—next he astounds us with the icy sublimities of the Pole (a fine summer panorama, by the way)—then to the glittering spires, minarets, and mosques of Constantinople—then to the infant world of New Holland—and back to the Old World, to enjoy scenes and sites which are hallowed in memory's fond shrine, by their association with the most glorious names and events in our history. We remember the philosophical amusement of the great Lord Shaftesbury, in contriving all the world in an acre in his retreat at Reigate: what his Lordship laboured to represent in his garden, Mr. Burford essays in his panoramas—in short, he gives us all the world on an acre—of canvass.

Reader, we do not hold the grand secret of life to be the art of hoaxing, when we tell you that for a Greenwich fare you may be transported to the classic regions of Italy—that a walk to Leicester Square will probably delight you more than a ride to Greenwich, little as we are inclined to underrate the last of the pleasures of the people. The contrast is forcible, and the intellectual advantage to be enjoyed in the metropolis too evident to be overlooked.

At the Panorama, Florence is in the upper circle, and Milan in the lower one. The main attraction of the latter is the celebrated cathedral, which forms, as it were, the nucleus of the scene. The point of view has been objected to, as the spectator is placed about mid-way up the cathedral, and thus looks down into the streets and squares of the city; but, it should be remembered, that he also enjoys the distant country, which he could not have done had the view been from the area of the city; and, as we have before said, the beauty of the paysage is one of the perfections of Mr. Burford's paintings. Its present success may be told from the Description:

"Beyond, the eye ranges to an immense distance over the rich and fertile plains of Lombardy, Piedmont, and the Venetian States, luxuriant with every description of rural beauty, intersected by rivers and lakes, and thickly studded with towns and villages, with their attendant gardens, groves, and vineyards. The Northern horizon, from East to West, is bounded by the vast chain of the Alps, which form a magnificent semicircle at from eighty to one hundred and twenty miles distant, Monte Rosa, Monte Cenis, Monte St. Gothard, the Simplon, &c. covered with eternal snow, being conspicuous from their towering height; towards the South the view is bounded by the Apennines, extending across the peninsula from the Mediterranean to the Adriatic; and on the South-west, the Piedmontese hills, in the neighbourhood of Turin, appear a faint purple line on the horizon, so small as to be scarcely visible; the purity of the atmosphere enables the eye to discern the most distant objects with accuracy, and the brilliant sunshine gives inconceivable splendour to every part of the scene; each antique spire and curiously-wrought tower sparkles brightly in its beams, whilst the dark foliage of fine trees, even in the heart of the city, relieves the eye, and produces a beautiful and pleasing effect."

The cathedral will be recollected as the finest specimen extant of pointed Gothic architecture, and termed by the Milanese, the eighth wonder of the world. It is entirely of white marble, and its highest point four hundred feet from the base. A better idea of its minute as well as vast beauty will be afforded by the reader turning to our engraving of the exterior in vol. xiv. of The Mirror. It is successfully painted in the Panorama, although it has not the dazzling whiteness that a stranger might expect; and, on it are those beautiful tinges which are thought to be shed by the atmosphere upon buildings of any considerable age. This effect is visible ever in the fine climate of Italy: it is ingeniously referred to by Sir Humphry Davy in his last work6 to the chemical agency of water. He speaks, however, rather of the decay produced by water, of which tinge is but the first stage. The latter is very pleasing, and, about two years since, the fine portico of the Colosseum, in the Regent's Park, was artificially coloured to produce this effect of time, as it has been poetically considered.

The City of Milan is not particularly interesting, though to an untravelled beholder, it has points of attraction. He may probably be struck with the vast extent of some of the structures when compared with the puny buildings of our own country and times; and the space occupied by the palaces will but remind him of the mistaken magnificence of Buckingham, or the gloomy grandeur of St. James's. Again, the plastered and fancifully coloured fronts of the dwelling-houses, their gay draperies, &c. but ill-assort with the heavy red-brick exteriors of our metropolis; although this contrast is to be sought elsewhere than in externals. Mr. Burford's summary, or characteristics of the city may be quoted:

"The form of the city is nearly circular, about ten miles in circumference, although perhaps the thickly built and more densely populated part may be confined to an area of half that size. There are several large and handsome squares, but the streets, with very few exceptions, are neither wide nor regular; the pavement is formed like that of Paris, of small, sharp pebbles, with occasionally a narrow footway on each side, and the addition of two (or in the wider streets four) strips of flat stones in the centre, forming a sort of railway, on which the carriage wheels run with great smoothness and very little noise. The churches, hospitals, establishments for the poor, and other public institutions, are numerous, and display all the richness and magnificence of Italian architecture, and are at the same time endowed on a most liberal scale; the ancient palaces of the nobles, vast and rude, bear stamp of the importance of the city in the middle ages, when they served as domestic fortresses and lodged well-appointed and numerous retinues; and although they cannot at present vie with those of Rome or Genoa, yet they display considerable architectural luxury, and contain fine collections of works of art; attached to many are large and well-stocked gardens, which add much to the beauty of the city. Very little regard is paid to regularity of appearance in the general buildings; they vary in height from two to five stories, and are built of brick, or granite from the Lago Maggiori, plastered, coloured, or ornamented, according to the taste of the owner; many are still without the luxury of glass in the windows; the shops are numerous and well furnished; their entrances, as well as those of the coffee-houses, are frequently defended only by a coloured drapery, which, with the silk tapestry hung at the church doors, and occasionally from the balconies, &c., has a gay and pleasing effect; indeed the whole appearance of the city is cheerful and flourishing."

The groupes and incidents in the streets will amuse the spectator. There is Policinel—the eternal Punch—with his audience, a short distance from the Cathedral. All over Europe, the most enlightened portion of the world, is this little Motley to be seen frolicking with flashes of satire; the motto for his proscenium should be hic et ubique.

One of the beauties of this Panorama is the masterly effect of the Italian sky. There are fewer cloudless days in Italy than the stranger may imagine, but Mr. Burford was fortunate in his season.

SPIRIT OF THE PUBLIC JOURNALS

CHIT CHAT OF THE DAY

There is a good share of pleasant patter in the following abridged from the Metropolitan.

"Every one says that I am an odd person; I presume I am, and so is every one else taken singly. I can prove that by Cocker. One and one make two—two is even, one is odd, I am but one. There's logic for you. I am also a rambler by temperament. I ramble my person at my own free will, and my mind rambles quite indifferent as to its intimate connexion with the former. I look at the stars, and my thoughts are of women—I look at the earth, and my thoughts run upon heaven—I frequent the opera, and moralize upon the world and its vanities—I sit in my pew at church, and my thoughts ramble every where in spite of my endeavours and those of the parson to boot—I live in town all the year, because it's the fashion to be here in the season, and because I prefer London most when I can walk about where there is nobody to interrupt me. In the season, I am allowed to walk into every body's house, very often get an invite to fill up an odd corner, and as there generally is an odd corner at every party, and I do not stand at a short notice, I eat more good dinners than most people. I am not a fool, and yet not too clever, so that poised in that happy medium, I hear all, see all, know a great deal of what is going on, and hold my tongue. When people inhabit their town houses, I spend the whole day going from one to the other. I consider a house the only safe part of the metropolis. Were I to frequent the street during the season, I am so apt to fall into a brown study, that I'm certain to be jostled until I am black and blue—I have found myself calculating an arithmetical problem at a crossing, and have not been aware of my danger until a pair of greys sixteen hands high in full trot have snorted in my face—I am an idler by profession, live at a club, sleep at chambers, and have just sufficient means to pay my way and indulge my disposition. But I've not stated why I particularly like town when it is empty. It is because I feel relieved of all the fashionable et ceteras. By the time the season is over I am tired of dinners, of wine, of the opera, the eternal announcement of visiters at parties and balls, the music, the exotics, the suppers, the rattling of carriages, and the rattling of tongues. I rejoice at last to find London en deshabille—I can then do as I please without any fear of losing my character as a fashionable man. I consider that I can in London extract more amusement in a given quantity of ground than at any other place. A street will occupy me for a whole day: with an indifferent coat, and nothing but silver in my waistcoat pocket, I stop at every shop-window and examine every thing. Should it so happen that the prices are affixed to every article displayed, I make it a rule to read every one of them. I know therefore when Urling's lace is remarkably cheap, the value of most articles of millinery, the relative demands for boots, shoes, and hats, and prices of 'reach-me-downs' at a ready-made warehouse. At a pawn-broker's shop-window I have passed two or three hours very agreeably in ascertaining the sums at which every variety of second-hand goods are 'remarkably cheap,' from a large folio Bible as divinity, flutes and flageolets as music, pictures and china as taste, gold and silver articles as luxury, wedding rings as happiness, and duelling pistols as death. I could not of course indulge in these peripatetic fancies during the season without losing caste, but there is a season for all things."

"Talking of pictures, by the way, what a marvellous falling off is there in Wilkie!—a misfortune arising, as I take it, from a struggle after novelty of style. There is a portrait of the King by him in Somerset House Exhibition, like nothing on earth but a White Lion on its hinder legs, and there was one a year or two since of George the Fourth in a Highland dress—a powerful representation of Lady Charlotte Bury, dressed for Norval. Look at that gem of art, his Blind Fiddler, now in the National Gallery, or at his Waterloo Gazette, or at the Rent Day, and compare any one of them with the senseless stuff he now produces, and grieve. His John Knox—ill placed for effect, as relates to its height from the ground, I admit; but look at that—flat as a teaboard—neither depth nor brilliancy. Knox himself strongly resembling in attitude the dragon weathercock on Bow steeple painted black. Has Wilkie become thus demented in compliment to Turner, the Prince of Orange (colour) of artists? Never did man suffer so severely under a yellow fever, and yet live so long. I dare say it is extremely bad taste to object to his efforts; but I am foolish enough to think that one of the chief ends of art is to imitate nature as closely as possible. Look, for instance, at Copley Fielding's splendid drawing in the Water Colour Exhibition, of vessels in a gale off Calshot; and certainly I have never yet seen any thing either animal or vegetable at all like the men, women, trees, grass, mountains, which appear in Mr. Turner's works.

"This is of course an individual opinion, but I think it may be expressed without any fear of incurring a charge of ill-nature, when one thing is recollected. Copley Fielding cannot be a bad artist; Prout cannot be a bad artist; Nash cannot be a bad artist; De Vint, Stanfield, Reinagle, Calcott, none of these can be called bad artists; yet not one of these gentlemen, eminent as they are, produce any thing like Turner's drawings. Now if they are all wrong, Mr. Turner is quite right; but it is utterly impossible he should be so, if they are.

"Everybody knows the story of the sign-painter in the country, who could paint nothing but a red lion; and accordingly he advised every inn-keeper and alehouse-keeper in the neighbouring village, who applied to him, to have the sign of the Red Lion. This did very well for a considerable time, and the painter practised so successfully that not a hamlet or town, for ten miles round, that had not its red lion; until at length a new-comer, who, like Daniel of old, thought there were quite as many lions round him as were wanted, suggested to the artist that he should like to have a swan for the sign of his small concern. In vain the painter protested, Boniface was resolute. 'Well,' said the rural Apelles, 'if you will have a swan you must, but you may rely upon it when it is finished, it will be so like a red lion, you would not know the difference.' So Turner, if he were to paint a blackbird, it would be so like a canary when it was finished, you would not know one from the other.

"Among other sights, I was induced to go and visit the 'Fleas,' last Saturday. Never was there such an imposition; instead of being harnessed, they were tied by the hind legs, and the combatants, poor wretches! were pinched by the tails in tweezers, and of course moved their legs in their agony. Well, thought I, as I went out, I have been in Spain, and Portugal, and Italy, and have passed many a restless night, but hang me if ever I was so flea bitten in my life as I have been to day; and I thought of my shilling and the old proverb.

"There is a picture of Lord Mulgrave in the Somerset House exhibition, very like, painted by Briggs. The best portrait there, is Pickersgill's Lord Hill; as a likeness, it is identity; and I admire it the more, from the total absence of what the painters call accessories. It is simple, and though honourably decorated, is unadorned by what is considered 'groscape' drapery; and yet Mr. Pickersgill was at one time an unqualified admirer of cloaks; every hawbuck of a fellow who sat to him, was wrapped up in a cloak: this he has conquered, and we rejoice at it. The portrait of Lady Coote is a good picture; it is a pity that her ladyship had not sat a few years earlier; but that is no affair of the painter. A picture of Lady Londonderry, in the costume of Queen Elizabeth, by a Frenchman is amazingly like. There is a story about this dress which only proves the advantages of making experiments before any grand display. The petticoat of the Virgin Queen, as personated by her ladyship, was so thickly covered with diamonds, that the substratum of material could scarcely be seen; and nothing could be more splendid than the effect; but the diamonds glittered all round the dress, behind and before, and at the side; and so long as her ladyship paraded the magnificent suite of her apartments, all was well, and all shone brilliantly; but lo and behold, when her ladyship threw herself gracefully on her mimic throne, she found that she might as well be sitting in her robe de chambre on a pebbly pavement, or a heap of flints just prepared for Macadamization. Stones, though precious, are still stones, and the jump the Marchioness gave when she first felt the full effect of her jewels, is described as something prodigious. So handsome a person, however, might easily dispense with such ornaments. A queen of hearts may always look down upon a mere queen of diamonds.