полная версия

полная версияПолная версия

The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 17, No. 485, April 16, 1831

Why was hunting formerly a very convenient resource for the wholesomeness, as well as luxury, of the table?

Because the natural pastures being then unimproved, and few kinds of fodder for cattle discovered, it was impossible to maintain the summer stock during the cold season. Hence a portion of it was regularly slaughtered and salted for winter provision. We may suppose, therefore, that when no alternative was offered but these salt meats, even the leanest venison was devoured with relish.—Hallam’s Hist. Middle Ages.

Why were all the great forests pierced by those long rectilinear alleys which appear in old prints, and are mentioned in old books?

Because the avenues were particularly necessary for those large parties, resembling our modern battues, where the honoured guests being stationed in fit standings, had an opportunity of displaying their skill in venery by selecting the buck which was in season, and their dexterity at bringing him down with the cross-bow or long-bow.

Why should a deer-park exhibit but little artificial arrangement in its disposal?

Because the stag, by nature one of the freest denizens of the forest, can only be kept even under comparative restraint, by taking care that all around him intimates a complete state of forest and wilderness. Thus, there ought to be a variety of broken ground, of copse-wood, and of growing timber—of land, and of water. The soil and herbage must be left in its natural state; the long fern, amongst which the fawns delight to repose, must not be destroyed.

Why did the common people formerly call the forest “good,” and the greenwood “merry?”

Because of the pleasure they took in the scenes themselves, as well as in the pastimes which they afforded.

Why is a short gallop called a canter?

Because of its abbreviation from Canterbury, the name of the pace used by the monks in going to that city.

Why was a certain noise called the “hunt’s-up?”

Because it was made to rouse a person in a morning; originally a tune played to wake the sportsmen, and call them together, the purport of which was, The hunt is up! which was the subject of hunting ballads also.

This expression is common among the older poets. One Gray, it is said, grew into good estimation with Henry VIII. and the Duke of Somerset, “for making certaine merry ballades, whereof one chiefly was, the hunte is up! the hunte is up!” Shakspeare has—

Since arm from arm that voice doth us affray,Hunting thee hence with hunts-up to the day.Romeo and Juliet.Again, in Drayton’s Polyolbion—

No sooner doth the earth her flow’ry bosom brave,At such time as the year brings on the pleasant spring,But hunts-up to the morn the feather’d sylvans sing.Why is a small hunting horn called a bugle?

Because of its origin from bugill, which means a buffalo, or perhaps any horned cattle. In the Scottish dialect it was bogle, or bowgill. Buffe, bugle, and buffalo, are all given by Barrett, as synonimous for the wild ox.—Nares’ Glossary.

Why is the stirrup so called?

Because of its origin from stigh-rope, from stigan ascendere, to mount; and thus termed by our Saxon ancestors, from a rope being used for mounting when stirrups began to be used in this island. It is evident, from various monuments of antiquity, that, at first, horsemen rode without either saddles or stirrups.

Why are sportsmen said to hunt counter?

Because they hunt the wrong way, and trace the scent backwards. Thus, in an old-work, Gentleman’s Recreations: “When the hounds or beagles hunt it by the heel, we say they hunt counter.” To hunt by the heel must be to go towards the heel instead of the toe of the game—i.e. backwards.—Nares.

WEATHER AT PARIS

It appears from observations made at the Royal Observatory in Paris, that, in the year 1830, the number of fine days was 164; of cloudy, 181; of rainy, 149; of foggy, 228; of frosty, 28; of snowy, 24; of sleety, 8; of thundery, 13. The wind was northerly 44 times; north-easterly, 23 times; easterly, 17 times; south-easterly, 23 times; southerly, 74 times; south-westerly, 69 times; westerly, 71 times; and north-westerly, 47 times.—New Monthly Magazine.

BEER HOUSES

It appears, from Parliamentary Returns, that five thousand three hundred and seventy-nine “beer houses” have been opened under the new Act in England and Wales; while the number of public-houses licensed is forty-five thousand six hundred and twenty-four. The number of beer-houses opened in Wales, is one thousand seven hundred and seventy-three, nearly half the number opened in all England—the number for England is three thousand six hundred and six.—Ib.

SAVINGS' BANKS

According to a Parliamentary Return just printed, the gross amount of sums received on account of savings’ banks is, since their establishment in 1817, 20,760,228l. Amount of sums paid, 5,648,338l. The balance therefore is, 15,111,890l. It also states that the gross amount of interest paid and credited to savings’ banks by the commissioners for the reduction of the national debt is, 5,141,410l. 8s. 7d.—Ibid.

SOAP

According to the Parliamentary Returns, the quantity of soap charged with the excise duty in great Britain, in the year ending the 5th of January, 1830, was—of hard soap, 103,041,961 lbs.; of soft soap, 9,068,918 lbs. In the year ending the 5th of January last, the quantity was—of hard, 117,324,320 lbs.; and of soft, 10,209,519 lbs. The number of licenses granted to soap-makers in the United Kingdom in the former year was 585, and in the latter 542.—Ib.

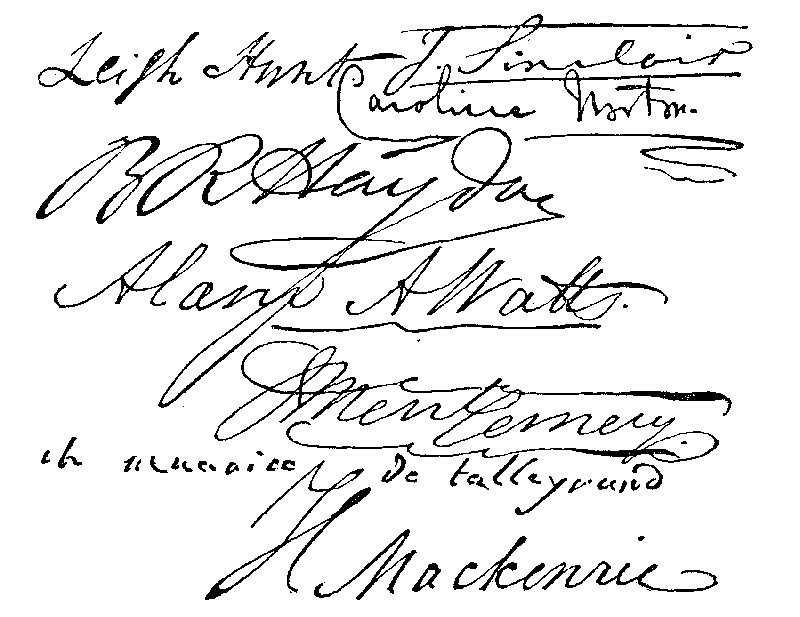

AUTOGRAPHS

We have the pleasure of resuming these innate illustrations of genius. Some of the present specimens are copied from the plate appended to the Edinburgh Literary Journal, whence the page in No. 478 of the Mirror was taken. First is

LEIGH HUNT.—Leigh Hunt’s writing is a good deal like the man: it is constrainedly easy, with an affectation of ornament, yet withal a good hand. The signature is copied from a letter written to a friend in Edinburgh, in 1820; and as one part of this letter is curious and interesting, we have pleasure in presenting it to our readers. We are inclined to believe that there are many good points about Leigh Hunt. We like the spirit of the following extract from his letter:—

“And this reminds me to tell you, that I am not the author of the book called the Scottish Fiddle, which I have barely seen. The name alone, if you had known me, would have convinced you that I could not have been the author. I had made quite mistakes enough about Sir Walter, not to have to answer for this too. I took him for a mere courtier and political bigot. When I read his novels, which I did very lately, at one large glut (with the exception of the Black Dwarf, which I read before), I found that when he spoke so charitably of the mistakes of kings and bigots, he spoke out of an abundance of knowledge, instead of narrowness, and that he could look with a kind eye also at the mistakes of the people. If I still think he has too great a leaning to the former, and that his humanity is a little too much embittered with spleen, I can still see and respect the vast difference between the spirit which I formerly thought I saw in him, and the little lurking contempts and misanthropies of a naturally wise and kind man, whose blood perhaps has been somewhat saddened by the united force of thinking and sickliness. He wishes us all so well that he is angry at not finding us better. His works occupy the best part of some book-shelves always before me, where they continually fill me with admiration for the author’s genius, and with regret for my petty mistakes about it.”—Edinburgh Literary Journal.

J. SINCLAIR—the signature of the venerable Sir John Sinclair, Bart., who has written and edited upwards of 25 useful works.

CAROLINE NORTON—the Honourable Mrs. Norton, author of the “Sorrows of Rosalie,” the “Undying One,” &c., and grand-daughter of the late Mr. Thomas Sheridan. This signature is from a superb portrait in a recent Number of the New Monthly Magazine: a lovelier and more intellectual head and front we never beheld.

B.R. HAYDON—peculiarly characteristic of the writer’s style of painting—large and bold. Whoever has seen his Napoleon, just opened for exhibition, must, we think, acknowledge the above identity. In our next Number we intend to notice the above triumph of art.

ALARIC A. WATTS—an elegant hand, worthy of the editor of the most elegant of the Annuals: this, however, is not Mr. Watts’s ordinary signature.

J. MONTGOMERY.—This hand is far more redundant in ornament than one would have expected from so gentle and talented a Quaker; but the Quaker has been lost in the poet, as an old grey wall is concealed under a luxuriant mantling of ivy. The autograph now engraved is copied from the signature attached to the original of his beautiful poem on Night, beginning—“Night is the time for rest.”—Edinburgh Literary Journ.

CH. MAURICE DE TALLEYRAND—whose life will hereafter be traced throughout a volume of the history of the last and present century. His age is 77. This signature is copied from the Frontispiece to the last edition to the Court and Camp of Bonaparte, in the Family Library, which is a fine portrait of Talleyrand, engraved by Finden, from a picture by Girard.

H. MACKENZIE—author of the Man of Feeling, &c. He died during the past year, in Edinburgh.

FINE ARTS

PANORAMA OF HOBART TOWN

Mr. R. Burford, the most successful panorama painter of his day, has lately completed a View of Hobart Town, Van Dieman’s Land, and the surrounding country, which he is now exhibiting in the Strand. It is not, perhaps, the most striking picture this ingenious artist has produced, yet it is certainly one of the most interesting. The embellishments of books of travels, the sketches of tourists, and the extravagant annual prints, have familiarized the stay-at-home reader with almost every city on the European continent; but a view in Van Dieman’s Land is much more of a novelty. It is comparatively a terra incognita, about which every one must feel some curiosity, though more rationally expressed than that of a King of Persia, who asked what sort of a place America was—“underground, or how?” For the purpose of giving a general idea of a country, a panoramic painting is well adapted: the size of the objects is at once natural, there is no straining of eyes to make them out, and the effect of the whole scene is that of being dropped in the midst of the country, and its surface at once spread before us.

Of Hobart Town we quote a brief description from Mr. Burford’s pamphlet, or key to the picture:—

“The capital and seat of government of Van Dieman’s Land, or Tasmania, is delightfully situated at the head of Sullivan’s Cove, on the south-east side of the river Derwent, about twelve miles from its mouth. The town is built on two small hills and the intermediate valley, the whole gently sloping towards the harbour from the foot of Mount Wellington—a rock which suddenly rears its snow-clad summit to the height of 4,000 feet. Through the centre of the town a rapid stream takes its course, giving motion to several mills, and affording a constant supply of most excellent water for all domestic purposes, as well as increasing the salubrity and beauty of the neighbourhood. From the summit of one of these hills, the present panorama was taken, which, although it does not include the buildings in the lowest part of the valley, exhibits every object particularly deserving notice, as well as the broad expanse of the Derwent, covered with ships, boats, &c. Beyond the town, and on the opposite side of the river, the eye ranges over a vast extent of country, richly variegated and diversified by gently rising hills, broad and verdant slopes, farms, and pasture lands, in the highest state of cultivation, presenting the most agreeable scenes, replete with the useful product of a rich soil and fine climate; the whole bounded by lofty mountains, clothed with rich and almost impervious forests of evergreens, occasionally intermixed with high and nearly perpendicular rocks, whose summits are, for a great part of the year, covered with snow;—the whole forming one of the most agreeable, picturesque, and romantic scenes that can be conceived.

“Van Dieman’s Land is, from north to south, one hundred and sixty miles in length; and from east to west, one hundred and forty-five miles in width; being separated from the main land by Bass’s Straits, which are nearly one hundred miles across. The whole island, which is, almost without exception, of the most fertile and beautiful description, is divided into two counties—Buckingham and Cornwall—of which Hobart Town and Dalrymple are the capitals: the distance between them is one hundred and twenty miles.

“Hobart Town contains at present, upwards of one thousand houses, and has a resident population exceeding seven thousand persons. The town is well planned, and the streets, which intersect each other at right angles, are wide, the law compelling persons who build to leave at least sixty feet in width for carriage and foot ways: they are Macadamized, and are, as well as the numerous bridges over the stream, kept in excellent condition by the chain gangs. The houses are generally built at a short distance from each other, and are partly surrounded with gardens, which, with a very little attention, not always bestowed, become very ornamented and useful, producing, not only the many beautiful trees and shrubs of the country, but every fruit, flower, and vegetable, common in England. The houses are generally of two, sometimes of three, stories in height, well built of brick or stone, and covered with shingles of the peppermint tree; some few are still only weather boarded. The bricks are of a good and durable quality, and the free-stone of a very beautiful description, but exceedingly dear. Many buildings are formed of rough hewn stone, stuccoed with a good white cement, which keeps very clean. Macquarrie-street, running in a straight line from the Pier, contains many very handsome public buildings and private houses, being the residences of the principal settlers, merchants, &c. Rents are in general very high;—a small house of four rooms and a kitchen, will let for sixty or eighty pounds per annum; and a large one, adapted for a store, will obtain from two to three hundred. It cannot be expected at this early period, that the public buildings should display much architectural ornament; it is sufficient that they are large, substantially built, and well adapted for the several purposes for which they were erected.—Besides the church, there is a Scotch church, a neat stone building, near the barracks; a Wesleyan meeting, a stuccoed building in Bathurst-street; and a small Catholic chapel in Patrick-street. There are several excellent academies, and a seminary for young ladies, where first-rate accomplishments are taught, and every possible care taken of the health and morals of their pupils, by Mrs. Midwood and Miss Shartland; there are also day charity schools, on the Lancastrian system, for the children of convicts, labourers, &c. The boarding houses and hotels are well conducted and comfortable; at the latter, every accommodation to be found in one of the best English inns may be had, but at a truly English price; the low public houses and the grog shops are of the vilest description. An active and vigilant police has been recently reorganised, under the superintendence of two officers from England, whose exertions are already attended with the most beneficial results.

“The climate is most salubrious, the mean temperature being 60 deg. Fahrenheit; the extremes, 36 deg. 80 deg. The spring usually commences in September; the summer in December; the autumn in April; and the winter, seven weeks of which is very severe, in June.”

The Panorama is well executed throughout, and in parts, with much delicacy and finish. The distant country, bays, and points, are for the most part delightfully painted. Here and there are spots which almost remind us of Virgil’s

--locos loetos, et amoena vireta,Fortunatorum nemorum, sedesque beatas:and, without any view to a transportable offence, a man might well wish to settle himself here “for life.”

Mr. Burford’s “Descriptions” are perhaps better drawn up than those of exhibitions in general. In the Keyplate before us, fifty-two points or objects are denoted, and further illustrated by half-a-dozen pages of letter-press.—In the town are seen the barracks; the governor’s, commissary’s, and judges’ residences; hotel, jail, lime-kilns, church, court-house, bank, hospital, treasury, pier, &c., and Mrs. Midwood’s seminary. Groups of convicts enliven the picture—we had almost said enlighten it, from recollection of the picking propensities to which hundreds of them are indebted for their abode here. They are deplorable specimens of fallen nature—such as may be seen in droves slinking to their work in the dock-yard at Portsmouth, or elsewhere, and still bearing the front of humanity in their begrimed features, but harrowing the spectator with painful recollections of their moral abandonment. One of the groups is a chain gang at work—breaking stones for the road—or, a last effort at self-improvement, by mending the ways of others. How different would these worthies appear in a rabble rout at a London fire, or in all the sleekness of civilization, as exhibited in the sundry avocations of picking a pocket, in easing a country gentleman of his uncrumpled or bright dividend, or studying our ease and comfort by helping themselves to all our houses contain without the rudeness of disturbing our slumbers. A neighbouring group of natives, though less sightly than these fallen sons of civilization, in a moral point of view, would be a happy contrast, could we but look into the hearts of both parties, and see what is passing therein.

But we are moralizing, and this may not be the most showy inducement for the reader to visit Mr. Burford’s Panorama, and admire its pictorial beauties. Let him do so; and before he leaves the place, turn about, and think for himself, and be assured there is good in every thing.

INK LITHOGRAPHY

An exquisite specimen of this branch of art, by the ingenious Mr. R. Martin, of Holborn, has hitherto escaped our notice. It was forwarded to us some weeks since, and accidentally mislaid. It is, however, never too late to be just—by saying that the performance before us, in clearness, delicacy, and finish, equals, if not exceeds, every specimen yet produced in this country, or those we have seen on or from the continent. The Drawing is about the size of two pages of the Mirror, and exhibits specimens of almost every branch of the art. Thus, there are fruit and flowers—an antique cross—a Gothic tomb—bust and ornamented pedestal—laurel wreath—the Corinthian capital and Egyptian architecture—wood scenery—a beautiful landscape—a portrait of Lord Clarendon—“Portrait of a Lady”—a storm on the sea-coast—anatomical picture—a crouching tiger—a charter, with the seal affixed, the latter extremely fine—a country plan, very delicate and clear—suit of ancient armour, &c. The etchy spirit of these subjects almost equals the finest work on copper, and its elaborateness proves to how great perfection English artists have already carried the art of drawing on stone. Compared with some of their early productions, the present is a marvel of art: it combines the perspicuity of a pen-and-ink drawing with the freedom and fine effect of chalk drawing. We hope to hear nothing more of the uncertainty of lithography.

PHILANTHROPY

Is the only consistent species of public love. A patriot may be honest in one thing, yet a knave in all else;—a philanthropist sees and seizes the whole of virtue.

SPIRIT OF THE PUBLIC JOURNALS

PUNCH AND JUDY

By a Modern PythagoreanOne day last summer I happened to be travelling in the coach between Lanark and Glasgow. There were only two inside passengers besides myself; viz. an elderly woman, and a gentleman, apparently about thirty years of age, who sported a fur cap, a Hessian cloak, and large moustaches. The former was, I think, about the most unpleasant person to look at I had ever seen. Her features were singularly harsh and forbidding. She was also perfectly taciturn, for she never opened her lips, but left me and the other passenger to keep up the conversation the best way we could. The young man I found to be a very pleasant and intelligent fellow—quite a gentleman in his manners; and apparently either an Oxon or a Cantab, for he talked much and well about the English universities, a subject on which I also happened to be tolerably conversant. But, agreeable as his conversation was, it could not prevent me from entertaining an unpleasant feeling—one almost amounting to dislike and hostility—against the female; whom I regarded, from the first moment, with singular aversion. We were not troubled, however, very long with her company, for she left us at Dalserf, about half way between Lanark and Hamilton.

“It is very curious, sir,” said I to the stranger when she had gone, “that I should feel so strangely annoyed as I have been with that woman. I absolutely know nothing about her, and cannot lay a single fault to her charge, but plain looks and taciturnity; and yet I feel as if no inducement would tempt me to step again into a coach where I knew she was to be present. And after all, for any thing I know to the contrary, she may be a very good woman.”

“Your feelings, sir,” answered he, “are remarkable, but by no means new; for I have myself been subject to a precisely similar train of emotions, and from a cause similar to yours. The thing is odd, I allow—what my friend, Coleridge, would call a psychological curiosity—but, I believe, every human being has at times felt it more or less. The unlucky woman who has proved such a source of annoyance to you, has been none whatever to me. She is plain-looked, to be sure, but it did not strike me that there was any thing peculiarly unpleasant in her aspect; and as for her silence, that, in my eyes, is no discommendation. So much for the different trains of emotions experienced by different persons from the same cause. There is, in truth, my dear sir, no accounting for such metaphysical phenomena. We must just take them as we find them, and be contented to know the effect while we remain in ignorance of the cause. Now, to show that you do not stand alone in such feelings, I shall, with your permission, relate an event which lately occurred to myself; on which occasion I was horribly annoyed by a circumstance in itself perfectly harmless and trivial, and which gave me much more disturbance than the taciturn lady who has just left us has given to you. My adventure, in truth, was attended with such extraordinary results, both to myself and another individual, that it possesses many of the characters of a genuine romance.” Having expressed my desire to hear what he had to relate on such a subject, he proceeded as follows:—

“The circumstance I allude to happened not long ago, while supping at the house of a literary friend in Edinburgh. On arriving, about nine in the evening, I was ushered into his library, where I found him, accompanied by two other friends; and in the short interval which elapsed before supper was announced, we amused ourselves looking at his books, and making comments upon such of them as struck our fancy. Our host was distinguished for learning; he was a man, in fact, of uncommon abilities, both natural and acquired; and the two guests who chanced to be with him were, in this particular, little inferior to himself. Among the other books which we happened to take up, was Punch and Judy, illustrated by the inimitable pencil of George Cruikshank. While looking at these capital delineations of the characters in the famous popular opera of the fairs, no particular emotion, save one of a good deal of pleasure, passed through my mind. I looked at them as I would do at any other humorous prints; and laying down the volume, thought no more of it at the time.