полная версия

полная версияThe Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 17, No. 485, April 16, 1831

Various

The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction / Volume 17, No. 485, April 16, 1831

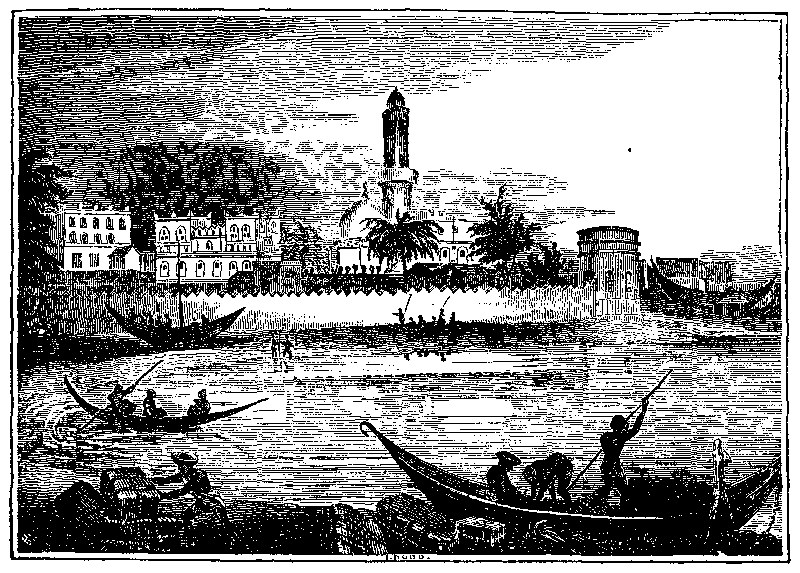

MOCHA

“Bon pour la digestion,” said the young Princess Esterhazy, when sent to bed by her governess without her dinner; we say the same of coffee; and hope the reader will think the same of Mocha, or the place whence the finest quality is exported.

Mocha, the coffee-drinker need not be told, is a place of some importance on the borders of the Red Sea, in that part of Arabia termed “Felix,” or “Happy.” “The town looks white and cheerful, the houses lofty, and have a square, solid appearance; the roadstead is almost open, being only protected by two narrow spits of sand—on one of which is a round castle, and the other an insignificant fort.”

Lord Valentia1 visited Mocha repeatedly during his examination of the shores of the Red Sea; and his description is the most full and minute:—

“Its appearance from the sea is, he says, tolerably handsome, as all the buildings are white-washed, and the minarets of the three mosques rise to a considerable height. The uniform line of the flat-roofed houses is also broken by several circular domes of kobbas, or chapels. On landing at a pier, which has been constructed for the convenience of trade, the effect is improved by the battlements of the walls, and a lofty tower on which cannon are mounted, which advances before the town, and is meant to protect the sea gate. The moment, however, that the traveller passes the gates, these pleasing ideas are put to flight by the filth that abounds in every street, and more particularly in the open spaces which are left within the walls, by the gradual decay of the deserted habitations which once filled them. The principal building in the town is the residence of the dola, which is large and lofty, having one front to the sea, and another to a square. Another side of the square, which is the only regular place in the town, is filled up by the official residence of the bas kateb, or secretary of state, and an extensive serai, built by the Turkish pacha during the time that Mocha was tributary to the Grand Seignior. These buildings externally have no pretensions to architectural elegance, yet are by no means ugly objects, from their turretted tops, and fantastic ornaments in white stucco. The windows are in general small, stuck into the wall in an irregular manner, closed with lattices, and sometimes opening into a wooden, carved-work balcony. In the upper apartments, there is generally a range of circular windows above the others, filled with thin strata of a transparent stone, which is found in veins in a mountain near Sanaa. None of these can be opened, and only a few of the lower ones, in consequence of which, a thorough air is rare in their houses; yet the people of rank do not seem oppressed by the heat, which is frequently almost insupportable to a European.

“The best houses are all facing the sea, and chiefly to the north of the sea gate. The British factory is a large and lofty building, but has most of the inconveniences of an Arab house.

“The town of Mocha is surrounded by a wall, which towards the sea is not above sixteen feet high, though on the land side it may, in some places, be thirty. In every part it is too thin to resist a cannon-ball, and the batteries along shore are unable to bear the shock of firing the cannon that are upon them.

“The climate of Mocha is extremely sultry,2 owing to its vicinity to the arid sands of Africa, over which the S.E. wind blows for so long a continuance, as not to be cooled in its short passage over the sea below the Straits Babel Mandel.

“Mocha, according to some learned natives, was not in existence four hundred years ago; from which period we know nothing of it, till the discoveries and conquests of the Portuguese in India opened the Red Sea to the natives of Europe.”

Mrs. Lushington, in her interesting Journey from Calcutta to Europe, says, “the coffee-bean is cultivated in the interior, and is thence brought to Mocha for exportation. The Arabs themselves use the husks, which make but an inferior infusion. Every lady who pays a visit, carries a small bag of coffee with her, which enables her ‘to enjoy society without putting her friends to expense.’”

Mocha coffee is in smaller berries than other kinds, and its flavour is extremely fine. Hundreds of pages have been written on the origin and introduction of coffee as a beverage. In the Coffee-drinker’s Manual, translated from the French, we find it dated at the middle of the seventeenth century, and in that quarter of Arabia wherein Mocha is situated.

ORIGIN OF THE HOUSE OF COMMONS

(To the Editor.)As a general reader of your entertaining miscellany, I take the liberty to correct a mistake in No. 481, relative to the Origin of the House of Commons, which is indirectly stated to have originated from the Battle of Evesham. It is true that the earliest instance on record of the assembling in parliament representatives of the people occurred in the same year with the battle of Evesham; but it had no connexion whatever with the event of that engagement, since the parliament (to which for the first time citizens and burgesses were summoned) was assembled through the influence of the Earl of Leicester, who then held the king under his control; and the meeting took place in the beginning of the year 1265, the writs of summons having been issued in November, 1264; while the battle of Evesham, in which the Earl of Leicester was killed, did not happen till August 4, 1265, or between five and six months after the conclusion of the parliament. From that period to the death of Henry III. in 1272, it does not appear that any election of citizens or burgesses, to attend parliament, occurred. The next instance of such elections seems to have happened in the 18th of Edward I.; and the first returns to such writs of summons extant are dated the 23rd of the same reign, since which, with a few intermissions, they have been regularly continued.

The correctness of these statements will appear from a reference to the 4th and 5th chapters of Sir W. Betham’s recently published work on “Dignities Feudal and Parliamentary,” or to Sir James Mackintosh’s History of England.

M.-–We admit that the battle of Evesham, literally speaking, was not the origin of the House of Commons, and wish our correspondent P.T.W. had furnished us with the name of the “modern writer” who has made the assertion. At the same time it must be conceded that the fall of Simon de Montfort, at Evesham, led to the more speedy consummation of the wished for object. Thus Sir James Mackintosh, History of England, vol. i. p. 236, says—

“Simon de Montfort, at the very moment of his fall, set the example of an extensive reformation in the frame of parliament, which, though his authority was not acknowledged by the punctilious adherents to the letter and forms of law, was afterwards legally adopted by Edward, and rendered the parliament of that year the model of the British parliament, and in a considerable degree affected the constitution of all other representative assemblies. It may indeed be considered as the practical discovery of popular representation. The particulars of the war are faintly discerned at the distance of six or seven centuries. The reformation of parliament, which first afforded proof from experience that liberty, order, greatness, power, and wealth, are capable of being blended together in a degree of harmony which the wisest men had not before believed to be possible, will be held in everlasting remembrance. He died unconscious of the imperishable name which he acquired by an act which he probably considered as of very small importance—the summoning a parliament, of which the lower house was composed, as it has ever since been formed, of knights of the shires, and members for cities and boroughs. He thus unknowingly determined that England was to be a free country; and he was the blind instrument of disclosing to the world that great institution of representation which was to introduce into popular governments a regularity and order far more perfect than had heretofore been purchased by submission to absolute power, and to draw forth liberty from confinement in single cities to a fitness for being spread over territories which, experience does not forbid us to hope, may be as vast as have ever been grasped by the iron gripe of a despotic conqueror. The origin of so happy an innovation is one of the most interesting objects of inquiry which occurs in human affairs; but we have scarcely any positive information on the subject; for our ancient historians, though they are not wanting in diligently recording the number and the acts of national assemblies, describe their composition in a manner too general to be instructive, and take little note of novelty or peculiarity in the constitution of that which was called by the Earl of Leicester.

“That assembly met at London, on the 22nd of January, 1265, according to writs still extant, and the earliest of their kind known to us, directing ‘the sheriffs to elect and return two knights for each county, two citizens for each city, and two burgesses for every burgh in the county.’ If this assembly be supposed to be the same which is vested with the power of granting supply by the Great Charter of John, the constitution must be thought to have undergone an extensive, though unrecorded, revolution in the somewhat inadequate space of only fifty years, which had elapsed since the capitulation of Runnymede; for in the Great Charter we find the tenants of the crown in chief alone expressly mentioned as forming with the prelates and peers the common council for purposes of taxation; and even they seem to have been required to give their personal attendance, the important circumstances of election and representation not being mentioned in the treaty with John;—neither does it contain any stipulation of sufficient distinctness applicable to cities and boroughs, for which the charter provides no more than the maintenance of their ancient liberties.

“Probably conjecture is all that can now be expected respecting the rise and progress of these changes. It is, indeed, beyond all doubt, that by the constitution, even as subsisting under the early Normans, the great council shared the legislative power with the king, as clearly as the parliament have since done.3 But these great councils do not seem to have contained members of popular choice; and the king, who was supported by the revenue of his demesnes, and by dues from his military tenants, does not appear at first to have imposed, by legislative authority, general taxes to provide for the security and good government of the community.—These were abstract notions, not prevalent in ages when the monarch was a lord paramount rather than a supreme magistrate. Many of the feudal perquisites had been arbitrarily augmented, and oppressively levied. These the Great Charter, in some cases, reduced to a certain sum; while it limited the period of military service itself. With respect to scutages and aids, which were not capable of being reduced to a fixed rate, the security adopted was, that they should never be legal, unless they were assented to at least by the majority of those who were to pay them. Now these were not the people at large, but the military tenants of the crown, who are accordingly the only persons entitled to be present at the great council to be holden for taxation. Very early, however, talliages had been exacted by the crown from those who were not military tenants; and this imposition daily grew in importance with the relaxation of the feudal tenures, and the increasing opulence of towns. The attempt of the barons to include talliage, and even the vague mention of the privileges of burghs, are decisive symptoms of this silent revolution. But the generally feudal character of the charter and the main object of its framers prevailed over that premature, but very honest, effort of the barons.”

We recommend the reader to turn to the pages succeeding the above extract, where the views of the enlightened author and statesman on the origin of our parliament are set forth in perspicuous and masterly style.

VISIT TO CORFE CASTLE

(From a Correspondent.)This is Corfe Castle! the celebrated structure, the date of which, and the founder of which, are lost in antiquity:

"It stands to tellA melancholy tale, to giveAn awful warning; soonOblivion will steal silentlyThe remnant of its fame."The castle is situate on the summit of a vast pyramidical mound, situated abruptly in an opening of the chalk range extending from Ballard Down to Worthbarrow in the Isle of Purbeck, county of Dorset. The walls are extremely thick, (12 feet in some places,) and are about half a mile in circuit. On the northern side the steepness of the ascent renders it inaccessible, and on the south is a deep ditch, over which is a bridge of three arches commanded by a gateway, flanked by two circular massive towers. The first ward has several towers. Passing onwards in a considerable ascent, we reached a second bridge guarded by a gate and towers, and entered the second ward, in which are the ruins of five towers. Winding round to the right, the explorer enters on the third and principal ward, which stands on the summit of the hill; here were the state apartments, store rooms, chapel, &c. built on vaults. The view from this portion of the ruin is magnificent. A wide expanse of flat country extending to Lytchett Bay and Poole, lies immediately at your feet. The gloomy fir trees wave in solemnity, and form in their darkness, a striking contrast with the dwellings that are scattered over the scene, and appear like specks of dazzling white; the estuary of Poole Harbour stretches along the distance like a mirror, and its molten silver-like appearance is broken here and there by small islands, among which Brownsea is conspicuous. Here we stood leaning over the northern battlement contemplating the face of a delightful country, smiling in peace,—from the stern and rugged fastness of war.

It was a bright summer’s day; strong masses of light and shade lay sleeping on the walls of the ruins, the dungeons were partially lighted by the rays which broke into their gloom, and it chanced to be a village holiday:

“Within the massy prison’s mouldering courts,Fearless and free the ruddy children played,Weaving gay chaplets for their innocent browsWith the green ivy and the red wall-flower,That mocks the dungeon’s unavailing gloom;The ponderous chains and gratings of strong iron,There rusted amid heaps of broken stoneThat mingled slowly with their native earth.There the broad beam of day, which feebly onceLighted the cheek of lean captivityWith a pale and sickly glare, then freely shoneOn the pure smiles of infant playfulness.No more the shuddering voice of hoarse despairPealed through the echoing vaults, but soothing notesOf joy fingered winds and gladsome birdsAnd merriment were resonant around.”Such were our feelings as we wandered musing and admiring amid the stupendous ruins of this once magnificent fabric.

“Now Time his dusky pennons o’er the scene,Closes in stedfast darkness.”The pomp of its splendour has passed away, and the stern wardour disputing entrance to the belted knight is now succeeded by a lank cobbler, who watches for lounging strangers, and acts as “Cicerone,” blending the most absurd and ridiculous stories in order to eke another sixpence from the purse of his auditor, and to add greater importance to himself; but he had a most amusing method of answering any startling questions as to date, by significantly observing in the purest Dorset dialect, “Why Lord love ye, zur, it wur avore the memory of ony maun in the parish!”

Apropos to dates, the earliest mention of Corfe is A.D. 978, when the Saxon annals narrate the murder of Edward, King of the West Saxons, committed here by his mother-in-law, Elfrida.

It was in the gloomy dungeons of this castle that King John starved to death twenty-two prisoners of war, many of whom were among the first nobility of Poictu, victims to the cruelty of a barbarous sceptered tyrant! Then again, we thought of the fate of Peter of Pontefract, the imprudent prophet, who, if he had turned over a page in the book of fate, should have folded down the leaf instead of incurring the monarch’s vengeance by meddling with state affairs.

It was in this fortress that the unfortunate Edward II. was murdered in 1372, by his cruel keepers, Sir John Maltravers, and Sir Thomas Gurney, who having removed the dethroned monarch from castle to castle, subjecting him to every hardship and indignity, hoping that ill-treatment might shorten his days. At last they determined amidst the profound security afforded by this impregnable castle, to effect his death in the most horrible manner, in order to prevent marks of violence being seen on his corpse, namely, by inserting a horn tube into his body, through which was conveyed a red-hot iron! Well may the traveller shudder at these ruins as they beetle over him in frowning ruggedness, for they have been the murderers’ den; and doubtless many a deed of slaughter has been committed in them, which has never come to light, under tyrannical power, which has never come to the knowledge of men or blotted the page of history.

The vast masses of the castle ruins which lie scattered about and in the vale below, form a scene of havoc and devastation, at once magnificent and impressive. The towers were blasted with gunpowder, and many

"Which do slopeTheir heads to their foundations,"appear as if they were yet staggering from the blast of the mine which sprung them from their beds; they lean as if ready to tumble down the steep sides of the hill, and appear as if a child’s finger would roll them headlong. The ruins are in the possession of the family of Bankes.

In a meadow in the vale on the west side, which leads, by the by, to Orchard Farm, is to be seen a curious earthwork, apparently ancient British, which, from its structure, might have been a place of druidical judicature, or for pastimes. This relic has, we believe, escaped the notice of the intelligent Rev. John Clavell of Kimmeridge; and if the public are ever to be favoured with the result of his studies and patient investigations, it will be one of the most extraordinary productions of its kind.

There is a small work on Corfe Castle, published by a very intelligent resident of Wareham; and we are in hopes that the grey and hoary ruins may call forth the muse of J.F. Pennie, who resides on this wild romantic district, and whom we met with pleasure in our rambles.

JAMES SILVESTER, SEN.NOTES OF A READER

KNOWLEDGE FOR THE PEOPLE; OR, THE PLAIN WHY AND BECAUSE

Part 6.–Sports and PastimesWe quote the following from HUNTING:

Why is it inferred that hunting was practised by the ancient Britons?

Because Dionysius (who lived 50 B.C.) says, that the inhabitants of the northern part of this island tilled no ground, but lived in great part upon the food they procured by hunting. Strabo (nearly contemporary) also says, that the dogs bred in Britain were highly esteemed upon the continent, on account of their excellent qualities for hunting.

Cæsar tells us, that venison constituted a great portion of their food; and as they had in their possession such dogs as were naturally prone to the chase, there can be little doubt that they would exercise them for procuring their favourite diet; besides, they kept large herds of cattle and flocks of sheep, both of which required protection from the wolves and other ferocious animals that infested the woods and coverts, and must frequently have rendered hunting an act of absolute necessity.—Strutt.

Why is hunting considered more ancient than hawking?

Because, in the earliest ages of the world, hunting was a necessary labour of self-defence, or the first law of nature, rather than a pastime; while hawking could never have been adopted from necessity, or in self-protection.

Why was hunting originally considered a royal and noble sport?

Because, as early as the ninth century, it formed an essential part of the education of a young nobleman. Alfred the Great was an expert and successful hunter before he was twelve years of age. Among the tributes imposed by Athelstan, upon a victory over Constantine, King of Wales, were “hawks and sharp-scented dogs, fit for hunting of wild beasts.” Edward the Confessor “took the greatest delight to follow a pack of swift hounds in pursuit of game, and to cheer them with his voice.”—Malmesbury. Harold, his successor, rarely travelled without his hawk and hounds. William the Norman, and his immediate successors, restricted hunting to themselves and their favourites. King John was particularly attached to field sports, and even treated the animals worse than his subjects. In the reign of Edward II. hunting was reduced to a perfect science, and rules established for its practice; these were afterwards extended by the master of the game belonging to Henry IV., and drawn up for the use of his son, Henry Prince of Wales, in two tracts, which are extant. Edward III., according to Froissart, while at war with France, and resident there, had with him sixty couple of stag-hounds, and as many hare-hounds, and every day hunted or hawked. Gaston, Earl of Foix, a foreign nobleman, contemporary with Edward, also kept six hundred dogs in his castle for hunting. James I. preferred hunting to hawking or shooting; so that it was said of him, “he divided his time betwixt his standish, his bottle, and his hunting; the last had his fair weather, the two former his dull and cloudy.”

Ladies’ hunting-dresses of the 15th century, as figured in Strutt’s Sports, &c., differ but little from the modern riding habit.

Why are greyhounds still petted by ladies?

Because in former times they were considered as valuable presents, especially among the ladies, with whom they appear to have been peculiar favourites. In an ancient metrical romance (Sir Eglamore), a princess tells the knight, that if he was inclined to hunt, she would, as an especial mark of her favour, give him an excellent greyhound, so swift that no deer could escape from his pursuit.—Strutt.

Why were certain forests called royal chases?

Because the privileges of hunting there were confined to the king and his favourites; and, to render these receptacles for the beasts of the chase more capacious, or to make new ones, whole villages were depopulated, and places of divine worship overthrown, not the least regard being paid to the miseries of the suffering inhabitants, or the cause of religion.—Strutt.

Why were lands first imparked?

Because their owners might still more effectually preserve deer and other animals for hunting.

A recent French newspaper gave notice of an association for the purpose of enabling persons of all ranks to enjoy the pleasures of the chase. A park of great extent is to be taken on lease near Paris; its extent is about six thousand acres, partly arable, and partly forest ground. The plan is, to open it to subscribers during six months—viz. from September 1 to March 1, an ample stock of game being secured in preserves.

Why were parks and inclosures usually attached to priories?

Because they were receptacles of game for the clergy of rank, who at all times had the privilege of hunting in their own possessions. At the time of the Reformation, the see of Norwich only was in the possession of no less than thirteen parks, well stocked with deer and other animals for the chase.—Spelman.

The eagerness of the clergy for hunting is described as irrepressible. Prohibitions of councils produced little effect. In some instances a particular monastery obtained a dispensation. Thus, that of St. Denis, in 774, represented to Charlemagne that the flesh of hunted animals was salutary for sick monks, and that their skins would serve to bind books in the library. Alexander III., by a letter to the clergy of Berkshire, dispenses with their keeping the archdeacon in dogs and hawks during his visitation.—Rymer. An archbishop of York, in 1321, carried a train of two hundred persons, who were maintained at the expense of the abbeys on his road, and who hunted with a pack of hounds from parish to parish!—Whitaker’s Hist. of Craven, quoted in Hallam’s Hist. Middle Ages.