полная версия

полная версияSea Power in its Relations to the War of 1812. Volume 2

The disaster to the "Essex" is connected by a singular and tragical link with the fate of an American cruiser of like adventurous enterprise in seas far distant from the Pacific. After the defeat at Valparaiso, Lieutenant Stephen Decatur McKnight and Midshipman James Lyman of the United States frigate were exchanged as prisoners of war against a certain number of officers and seamen belonging to one of the "Essex's" prizes; which, having continued under protection of the neutral port, had undergone no change of belligerent relation by the capture of her captor. When the "Essex Junior" sailed, these two officers remained behind, by amicable arrangement, to go in the "Phœbe" to Rio Janeiro, there to give certain evidence needed in connection with the prize claims of the British frigate; which done, it was understood they would be at liberty to return to their own country by such conveyance as suited them. After arrival in Rio, the first convenient opportunity offering was by a Swedish brig sailing for Falmouth, England. In her they took passage, leaving Rio August 23, 1814. On October 9 the brig fell in with the United States sloop of war "Wasp," in mid-ocean, about three hundred miles west of the Cape Verde Islands, homeward bound. The two passengers transferred themselves to her. Since this occurrence nothing further has ever been heard of the American ship; nor would the incident itself have escaped oblivion but for the anxiety of friends, which after the lapse, of time prompted systematic inquiry to ascertain what had become of the missing officers.

The captain of the "Wasp" was Master-Commandant, or, as he would now be styled, Commander Johnstone Blakely; the same who had commanded the "Enterprise" up to a month before her engagement with the "Boxer," when was demonstrated the efficiency to which he had brought her ship's company. He sailed from Portsmouth, New Hampshire, May 1, 1814. Of his instructions,245 the most decisive was to remain for thirty days in a position on the approaches to the English Channel, about one hundred and fifty miles south of Ireland, in which neighborhood occurred the most striking incidents of the cruise. On the outward passage was taken only one prize, June 2. She was from Cork to Halifax, twelve days out; therefore probably from six to eight hundred miles west of Ireland. The second, from Limerick for Bordeaux, June 13, would show the "Wasp" on her station; on which, Blakely reported, it was impossible to keep her, even approximately, being continually drawn away in pursuit, and often much further up the English Channel than desired, on account of the numerous sails passing.246 When overhauled, most of these were found to be neutrals. Nevertheless, seven British merchant vessels were taken; all of which were destroyed, except one given up to carry prisoners to England.

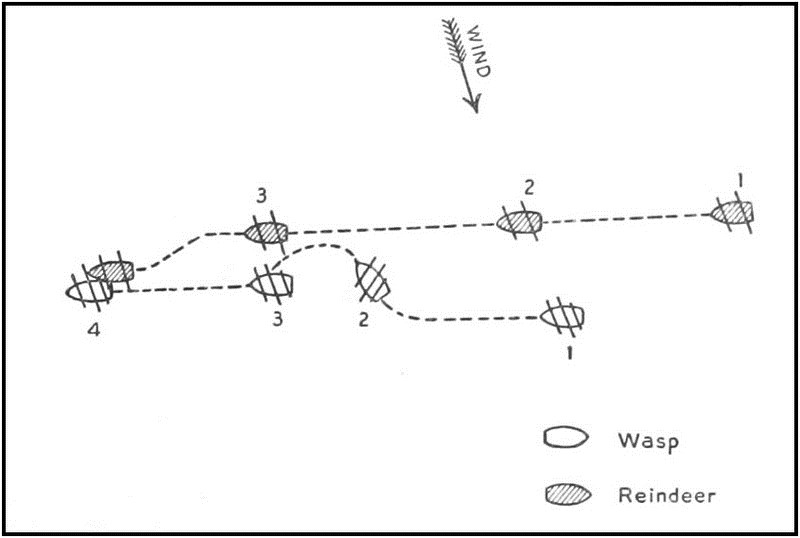

While thus engaged, the "Wasp" on June 28 sighted a sail, which proved to be the British brig of war "Reindeer," Captain Manners, that had left Plymouth six days before. The place of this meeting was latitude 48-½° North, longitude 11° East; therefore nearly in the cruising ground assigned to Blakely by his instructions. The antagonists were unequally matched; the American carrying twenty 32-pounder carronades and two long guns, the British sixteen 24-pounders and two long; a difference against her of over fifty per cent. The "Reindeer" was to windward, and some manœuvring took place in the respective efforts to keep or to gain this advantage. In the end the "Reindeer" retained it, and the action began with both on the starboard tack, closehauled, the British sloop on the weather quarter of the "Wasp,"—behind, but on the weather side, which in this case was to the right (1). Approaching slowly, the "Reindeer" with great deliberation fired five times, at two-minute intervals, a light gun mounted on her forecastle, loaded with round and grape shot. Finding her to maintain this position, upon which his guns would not train, Blakely put the helm down, and the "Wasp" turned swiftly to the right (2), bringing her starboard battery to bear. This was at 3.26 P.M. The action immediately became very hot, at very close range (3), and the "Reindeer" was speedily disabled. The vessels then came together (4), and Captain Manners, who by this time had received two severe wounds, with great gallantry endeavored to board with his crew, reduced by the severe punishment already inflicted to half its originally inferior numbers. As he climbed into the rigging, two balls from the "Wasp's" tops passed through his head, and he fell back dead on his own deck. No further resistance was offered, and the "Wasp" took possession. She had lost five killed and twenty-one wounded, of whom six afterwards died. The British casualties were twenty-three killed and forty-two wounded. The brig herself, being fairly torn to pieces, was burned the next day.247

Diagram of the Wasp vs. Reindeer battle

The results of this engagement testify to the efficiency and resolution of both combatants; but a special meed of praise is assuredly due to Captain Manners, whose tenacity was as marked as his daring, and who, by the injury done to his stronger antagonist, demonstrated both the thoroughness of his previous general preparation and the skill of his management in the particular instance. Under his command the "Reindeer" had become a notable vessel in the fleet to which she belonged; but as equality in force is at a disadvantage where there is serious inferiority in training and discipline, so the best of drilling must yield before decisive superiority of armament, when there has been equal care on both sides to insure efficiency in the use of the battery. To Blakely's diligence in this respect his whole career bears witness.

After the action Blakely wished to remain cruising, which neither the condition of his ship nor her losses in men forbade; but the number of prisoners and wounded compelled him to make a harbor. He accordingly went into L'Orient, France, on July 8. Despite the change of government, and the peace with Great Britain which attended the restoration of the Bourbons, the "Wasp" was here hospitably received and remained for seven weeks refitting, sailing again August 27. By September 1 she had taken and destroyed three more enemy's vessels; one of which was cut out from a convoy, and burnt under the eyes of the convoying 74-gun ship. At 6.30 P.M. of September 1 four sails were sighted, from which Blakely selected to pursue the one most to windward; for, should this prove a ship of war, the others, if consorts, would be to leeward of the fight, less able to assist. The chase lasted till 9.26, when the "Wasp" was near enough to see that the stranger was a brig of war, and to open with a light carronade on the forecastle, as the "Reindeer" had done upon her in the same situation. Confident in his vessel, however, Blakely abandoned this advantage of position, ran under his antagonist's lee to prevent her standing down to join the vessels to leeward, and at 9.29 began the engagement, being then on her lee bow. At ten the "Wasp" ceased firing and hailed, believing the enemy to be silenced; but receiving no reply, and the British guns opening again, the combat was renewed. At 10.12, seeing the opponent to be suffering greatly, Blakely hailed again and was answered that the brig had surrendered. The "Wasp's" battery was secured, and a boat was in the act of being lowered to take possession, when a second brig was discovered close astern. Preparation was made to receive her and her coming up awaited; but at 10.36 the two others were also visible, astern and approaching. The "Wasp" then made sail, hoping to decoy the second vessel from her supports; but the sinking condition of the one first engaged detained the new-comer, who, having come within pistol-shot, fired a broadside which took effect only aloft, and then gave all her attention to saving the crew of her comrade. As the "Wasp" drew away she heard the repeated signal guns of distress discharged by her late adversary, the name of which never became known to the captain and crew of the victorious ship.248

The vessel thus engaged was the British brig "Avon," of sixteen 32-pounder carronades, and two long 9-pounders; her force being to that of the "Wasp" as four to five. Her loss in men was ten killed and thirty-two wounded; that of the "Wasp" two killed and one wounded. The "Avon" being much superior to the "Reindeer," this comparatively slight injury inflicted by her testifies to inferior efficiency. The broadside of her rescuer, the "Castilian," of the same weight as her own, wholly missed the "Wasp's" hull, though delivered from so near; a circumstance which drew from the British historian, James, the caustic remark that she probably would have done no better than the "Avon," had the action continued. The "Wasp" was much damaged in sails and rigging; the "Avon" sank two hours and a half after the "Wasp" left her and one hour after being rejoined by the "Castilian."

The course of the "Wasp" after this event is traced by her captures. The meeting with the "Avon" was within a hundred miles of that with the "Reindeer." On September 12 and 14, having run south three hundred and sixty miles, she took two vessels; being then about two hundred and fifty miles west from Lisbon. On the 21st, having made four degrees more southing, she seized the British brig "Atalanta," a hundred miles east of Madeira. This prize being of exceptional value, Blakely decided to send her in, and she arrived safely at Savannah on November 4, in charge of Midshipman David Geisinger, who lived to become a captain in the navy.249 She brought with her Blakely's official despatches, including the report of the affair with the "Avon." This was the last tidings received from the "Wasp" until the inquiries of friends elicited the fact that the two officers of the "Essex" had joined her three weeks after the capture of the "Atalanta," nine hundred miles farther south. Besides these, there were among the lost two lieutenants who had been in the "Constitution" when she took the "Guerrière" and the "Java," and one who had been in the "Enterprise" in her action with the "Boxer."

Coincident in time with the cruise of the "Wasp" was that of her sister ship, the "Peacock"; like her also newly built, and named after the British brig sunk by Captain Lawrence in the "Hornet." The finest achievement of the "Wasp," however, was near the end of her career, while it fell to the "Peacock" to begin with a successful action. Having left New York early in March, she went first to St. Mary's, Georgia, carrying a quantity of warlike stores. In making this passage she was repeatedly chased by enemies. Having landed her cargo, she sailed immediately and ran south as far as one of the Bahama Islands, called the Great Isaac, near to which vessels from Jamaica and Cuba bound to Europe must pass, because of the narrowness of the channel separating the islands from the Florida coast. In this neighborhood she remained from April 18 to 24, seeing only one neutral and two privateers, which were pursued unsuccessfully. This absence of unguarded merchant ships, coupled with the frequency of hostile cruisers met before, illustrates exactly the conditions to which attention has been repeatedly drawn, as characterizing the British plan of action in the Western Atlantic. Learning that the expected Jamaica convoy would be under charge of a seventy-four, two frigates, and two sloops, and that the merchant ships in Havana, fearing to sail alone, would await its passing to join, Captain Warrington next stood slowly to the northward, and on April 29, off Cape Canaveral, sighted four sail, which proved to be the British brig "Epervier" of eighteen 32-pounder carronades,250 also northward bound, with three merchant vessels under her convoy; one of these being Russian, and one Spanish, belonging therefore to nations still at war with France, though neutral towards the United States. The third, a merchant brig, was the first British commercial vessel seen since leaving Savannah.

As usual and proper, the "Epervier," seeing that the "Peacock" would overtake her and her convoy, directed the latter to separate while she stood down to engage the hostile cruiser. The two vessels soon came to blows. The accounts of the action on both sides are extremely meagre, and preclude any certain statement as to manœuvres; which indeed cannot have been material to the issue reached. The "Epervier," for reasons that will appear later, fought first one broadside and then the other; but substantially the contest appears to have been maintained side to side. From the first discharge of the "Epervier" two round shot struck the "Peacock's" foreyard nearly in the same place, which so weakened the spar as to deprive the ship of the use of her foresail and foretopsail; that is, practically, of all sail on the foremast. Having thenceforth only the jibs for headsail, she had to be kept a little off the wind. The action lasted forty-five minutes, when the "Epervier" struck. Her loss in men was eight killed, and fifteen wounded; the "Peacock" had two wounded.

In extenuation of this disproportion in result, James states that in the first broadside three of the "Epervier's" carronades were unshipped; and that, when those on the other side were brought into action by tacking, similar mishaps occurred. Further, the moment the guns got warm they drew out the breeching bolts. Allowing full force to these facts, they certainly have some bearing on the general outcome; but viewed with regard to the particular question of efficiency, which is the issue of credit in every fight,251 there remains the first broadside, and such other discharges as the carronades could endure before getting warm. The light metal of those guns indisputably caused them to heat rapidly, and to kick nastily; but it can scarcely be considered probable that the "Epervier" was not able to get in half a dozen broadsides. The result, two wounded, establishes inefficiency, and a practical certainty of defeat had all her ironwork held; for the "Peacock," though only three months commissioned, was a good ship under a thoroughly capable and attentive captain. A comical remark of James in connection with this engagement illustrates the weakness of prepossession, in all matters relating to Americans, which in him was joined to a painstaking accuracy in ascertaining and stating external facts. "Two well-directed shot," he says, disabled the "Peacock's" foreyard. It was certainly a capital piece of luck for the "Epervier" that her opponent at the outset lost the use of one of her most important spars; but the implication that the shot were directed for the point hit is not only preposterous but, in a combat between vessels nearly equal, depreciatory. The shot of a first broadside had no business to be so high in the air.

James alleges also poor quality and a mutinous spirit in the crew, and that at the end, when their captain called upon them to board, they refused, saying, "She is too heavy for us." To this the adequate reply is that the brig had been in commission since the end of 1812,—sixteen months; time sufficient to bring even an indifferent crew to a very reasonable degree of efficiency, yet not enough to cause serious deterioration of material. That after the punishment received the men refused to board, if discreditable to them under the conditions, is discreditable also to the captain; not to his courage, but to his hold upon the men whom he had commanded so long. The establishment of the "Epervier's" inefficiency certainly detracts from the distinction of the "Peacock's" victory; but it was scarcely her fault that her adversary was not worthier, and it does not detract from her credit for management and gunnery, considering that the combat began with the loss of her own foresails, and ended with forty-five shot in the hull, and five feet of water in the hold, of her antagonist.

By dark of the day of action the prize was in condition to make sail, and the "Peacock's" yard had been fished and again sent aloft. The two vessels then steered north for Savannah. The next evening two British frigates appeared. Captain Warrington directed the "Epervier" to keep on close along shore, while he stood southward to draw away the enemy. This proved effective; the "Epervier" arriving safely May 2 at the anchorage at the mouth of the Savannah River, where the "Peacock" rejoined her on the 4th. The "Adams," Captain Morris, was also there; having arrived from the coast of Africa on the day of the fight, and sailing again a week after it, May 5, for another cruise.

On June 4 the "Peacock" also started upon a protracted cruise, from which she returned to New York October 30, after an absence of one hundred and forty-seven days.252 She followed the Gulf Stream, outside the line of British blockaders, to the Banks of Newfoundland, thence to the Azores, and so on to Ireland; off the south of which, between Waterford and Cape Clear, she remained for four days. After this she passed round the west coast, and to the northward as far as Shetland and the Faroe Islands. She then retraced her course, crossed the Bay of Biscay, and ran along the Portuguese coast; pursuing in general outline the same path as that in which the "Wasp" very soon afterwards followed. Fourteen prizes were taken; of which twelve were destroyed, and two utilized as cartels to carry prisoners to England. Of the whole number, one only was seized from September 2, when the ship was off the Canaries, to October 12, off Barbuda in the West Indies; and none from there to the United States. "Not a single vessel was seen from the Cape Verde to Surinam," reported Warrington; while in seven days spent between the Rock of Lisbon and Cape Ortegal, at the northwest extremity of the Spanish peninsula, of twelve sail seen, nine of which were spoken, only two were British.

In these conditions were seen, exemplified and emphasized, the alarm felt and precautions taken, by both the mercantile classes and the Admiralty, in consequence of the invasion of European waters by American armed vessels, of a class and an energy unusually fitted to harass commerce. The lists of American prizes teem with evidence of extraordinary activity, by cruisers singularly adapted for their work, and audacious in proportion to their confidence of immunity, based upon knowledge of their particular nautical qualities. The impression produced by their operations is reflected in the representations of the mercantile community, in the rise of insurance, and in the stricter measures instituted by the Admiralty. The Naval Chronicle, a service journal which since 1798 had been recording the successes and supremacy of the British Navy, confessed now that "the depredations committed on our commerce by American ships of war and privateers have attained an extent beyond all former precedent.... We refer our readers to the letters in our correspondence. The insurance between Bristol and Waterford or Cork is now three times higher than it was when we were at war with all Europe. The Admiralty have been overwhelmed with letters of complaint or remonstrance."253 In the exertions of the cruisers the pace seems to grow more and more furious, as the year 1814 draws to its close amid a scene of exasperated coast warfare, desolation, and humiliation, in America; as though they were determined, amid all their pursuit of gain, to make the enemy also feel the excess of mortification which he was inflicting upon their own country. The discouragement testified by British shippers and underwriters was doubtless enhanced and embittered by disappointment, in finding the movement of trade thus embarrassed and intercepted at the very moment when the restoration of peace in Europe had given high hopes of healing the wounds, and repairing the breaches, made by over twenty years of maritime warfare, almost unbroken.

In London, on August 17, 1814, directors of two insurance companies presented to the Admiralty remonstrances on the want of protection in the Channel; to which the usual official reply was made that an adequate force was stationed both in St. George's Channel and in the North Sea. The London paper from which this intelligence was taken stated that premiums on vessels trading between England and Ireland had risen from an ordinary rate of less than one pound sterling to five guineas per cent. The Admiralty, taxed with neglect, attributed blame to the merchant captains, and announced additional severity to those who should part convoy. Proceedings were instituted against two masters guilty of this offence.254 September 9, the merchants and shipowners of Liverpool remonstrated direct to the Prince Regent, going over the heads of the Admiralty, whom they censured. Again the Admiralty alleged sufficient precautions, specifying three frigates and fourteen sloops actually at sea for the immediate protection of St. George's Channel and the western Irish coast against depredations, which they nevertheless did not succeed in suppressing.255

At the same time the same classes in Glasgow were taking action, and passing resolutions, the biting phrases of which were probably prompted as much by a desire to sting the Admiralty as by a personal sense of national abasement. "At a time when we are at peace with all the rest of the world, when the maintenance of our marine costs so large a sum to the country, when the mercantile and shipping interests pay a tax for protection under the form of convoy duty, and when, in the plenitude of our power, we have declared the whole American coast under blockade, it is equally distressing and mortifying that our ships cannot with safety traverse our own channels, that insurance cannot be effected but at an excessive premium, and that a horde of American cruisers should be allowed, unheeded, unmolested, unresisted, to take, burn, or sink our own vessels in our own inlets, and almost in sight of our own harbours."256 In the same month the merchants of Bristol, the position of which was comparatively favorable to intercourse with Ireland, also presented a memorial, stating that the rate of insurance had risen to more than twofold the amount at which it was usually effected during the continental war, when the British Navy could not, as it now might, direct its operations solely against American cruisers. Shipments consequently had been in a considerable degree suspended. The Admiralty replied that the only certain protection was by convoy. This they were ready to supply but could not compel, for the Convoy Act did not apply to trade between ports of the United Kingdom.

This was the offensive return made by America's right arm of national safety; the retort to the harrying of the Chesapeake, and of Long Island Sound, and to the capture and destruction of Washington. But, despite the demonstrated superiority of a national navy, on the whole, for the infliction of such retaliation, even in the mere matter of commerce destroying,—not to speak of confidence in national prowess, sustained chiefly by the fighting successes at sea,—this weighty blow to the pride and commerce of Great Britain was not dealt by the national Government; for the national Government had gone to war culpably unprepared. It was the work of the people almost wholly, guided and governed by their own shrewdness and capacity; seeking, indeed, less a military than a pecuniary result, an indemnity at the expense of the enemy for the loss to which they had been subjected by protracted inefficiency in administration and in statesmanship on the part of their rulers. The Government sat wringing its hands, amid the ruins of its capital and the crash of its resources; reaping the reward of those wasted years during which, amid abounding warning, it had neglected preparation to meet the wrath to come. Monroe, the Secretary of State, writing from Washington to a private friend, July 3, 1814, said, "Even in this state, the Government shakes to the foundation. Let a strong force land anywhere, and what will be the effect?" A few months later, December 21, he tells Jefferson, "Our finances are in a deplorable state. The means of the country have scarcely yet been touched, yet we have neither money in the Treasury nor credit."257 This statement was abundantly confirmed by a contemporary official report of the Secretary of the Treasury. At the end of the year, Bainbridge, commanding the Boston navy yard, wrote the Department, "The officers and men of this station are really suffering for want of pay due them, and articles now purchased for the use of the navy are, in consequence of payment in treasury notes, enhanced about thirty per cent. Yesterday we had to discharge one hundred seamen, and could not pay them a cent of their wages. The officers and men have neither money, clothes, nor credit, and are embarrassed with debts."258 No wonder the privateers got the seamen.