полная версия

полная версияSea Power in its Relations to the War of 1812. Volume 2

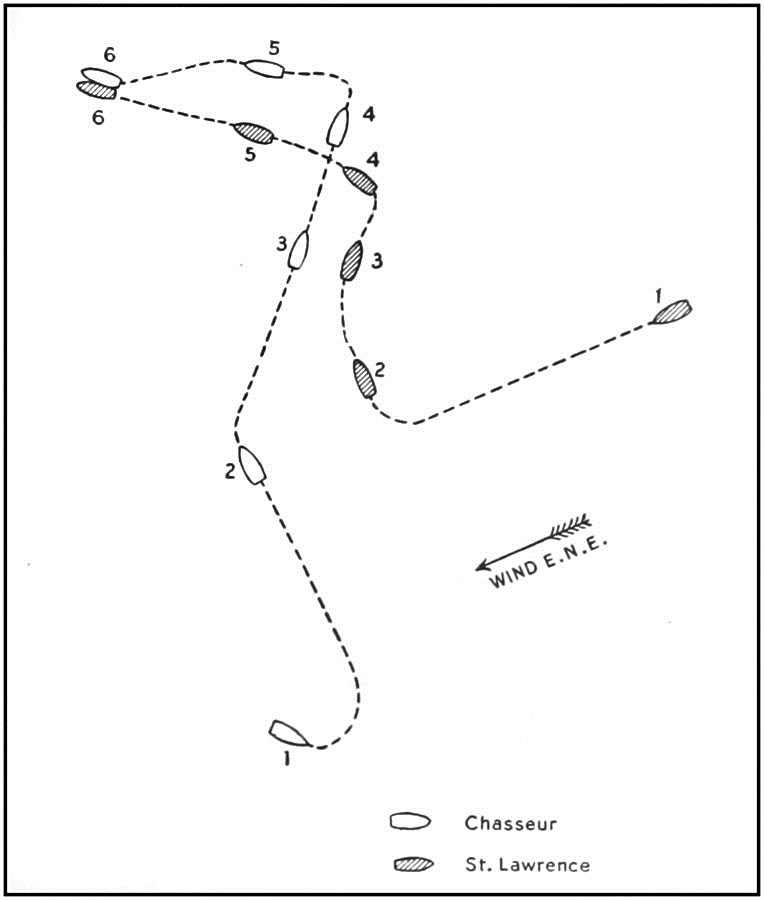

Believing from appearances that he had before him a weakly armed vessel making a passage, and seeing but few men on her deck, Captain Boyle pressed forward without much preparation and under all sail. At 1.26 P.M. the "Chasseur" had come within pistol-shot (3), on the port side, when the enemy disclosed a tier of ten ports and opened his broadside, with round shot, grape, and musket balls. The American schooner, having much way on, shot ahead, and as she was to leeward in doing so, the British vessel kept off quickly (4) to run under her stern and rake. This was successfully avoided by imitating the movement (4), and the two were again side by side, but with the "Chasseur" now to the right (5). The action continued thus for about ten minutes, when Boyle found his opponent's battery too heavy for him. He therefore ran alongside (6), and in the act of boarding the enemy struck. She proved to be the British schooner "St. Lawrence," belonging to the royal navy; formerly a renowned Philadelphia privateer, the "Atlas." Her battery, one long 9-pounder and fourteen 12-pounder carronades, would have been no very unequal match for the sixteen of her antagonist; but the "Chasseur" had been obliged recently to throw overboard ten of these, while hard chased by the Barrosa frigate, and had replaced them with some 9-pounders from a prize, for which she had no proper projectiles. The complement allowed the "St. Lawrence" was seventy-five, though it does not seem certain that all were on board; and she was carrying also some soldiers, marines, and naval officers, bound to New Orleans, in ignorance probably of the disastrous end of that expedition. The "Chasseur" had eighty-nine men, besides several boys. The British loss reported by her captain was six killed and seventeen wounded; the American, five killed and eight wounded.238

Diagram of the Chasseur vs. St. Lawrence battle

This action was very creditably fought on both sides, but to the American captain belongs the meed of having not only won success, but deserved it. His sole mistake was the over-confidence in what he could see, which made him a victim to the very proper ruse practised by his antagonist in concealing his force. His manœuvring was prompt, ready, and accurate; that of the British vessel was likewise good, but a greater disproportion of injury should have resulted from her superior battery. In reporting the affair to his owners, Captain Boyle said, apologetically: "I should not willingly, perhaps, have sought a contest with a King's vessel, knowing that is not our object; but my expectations at first were a valuable vessel, and a valuable cargo also. When I found myself deceived, the honor of the flag intrusted to my care was not to be disgraced by flight." The feeling expressed was modest as well as spirited, and Captain Boyle's handsome conduct merits the mention that the day after the action, when the captured schooner was released as a cartel to Havana, in compassion to her wounded, the commander of the "St. Lawrence" gave him a letter, in the event of his being taken by a British cruiser, testifying to his "obliging attention and watchful solicitude to preserve our effects, and render us comfortable during the short time we were in his possession;" in which, he added, the captain "was carefully seconded by all his officers."239

These instances, occurring either in the West Indies, or, in the case of the "Kemp," affecting vessels which had just loaded there, are sufficient, when taken in connection with those before cited from other quarters of the globe, to illustrate the varied activities and fortunes of privateering. The general subject, therefore, need not further be pursued. It will be observed that in each case the cruiser acts on the offensive; being careful, however, in choosing the object of attack, to avoid armed ships, the capture of which seems unlikely to yield pecuniary profit adequate to the risk. The gallantry and skill of Captain Boyle of the "Chasseur" made particularly permissible to him the avowal, that only mistake of judgment excused his committing himself to an encounter which held out no such promise; and it may be believed that the equally capable Captain Diron, if free to do as he pleased, would have chosen the packet, and not her escort the "Dominica," as the object of his pursuit. This the naval schooner of course could not permit. It was necessary, therefore, first to fight her; and, although she was beaten, the result of the action was to insure the escape of the ship under her charge. These examples define exactly the spirit and aim of privateering, and distinguish them from the motives inspiring the ship of war. The object of the privateer is profit by capture; to which fighting is only incidental, and where avoidable is blamable. The mission of a navy on the other hand is primarily military; and while custom permitted the immediate captor a share in the proceeds of his prizes, the taking of them was in conception not for direct gain, personal or national, but for injury to the enemy.

It may seem that, even though the ostensible motive was not the same, the two courses of operation followed identical methods, and in outcome were indistinguishable. This is not so. However subtle the working of the desire for gain upon the individual naval officer, leading at times to acts of doubtful propriety, the tone and spirit of a profession, even when not clearly formulated in phrase and definition, will assert itself in the determination of personal conduct. The dominating sense of advantage to the state, which is the military motive, and the dominating desire for gain in a mercantile enterprise, are very different incentives; and the result showed itself in a fact which has never been appreciated, and perhaps never noted, that the national ships of war were far more effective as prize takers than were the privateers. A contrary impression has certainly obtained, and was shared by the present writer until he resorted to the commonplace test of adding up figures.

Amid much brilliant achievement, privateering, like all other business pursuits, had also a large and preponderant record of unsuccess. The very small number of naval cruisers necessarily yielded a much smaller aggregate of prizes; but when the respective totals are considered with reference to the numbers of vessels engaged in making them, the returns from the individual vessels of the United States navy far exceed those from the privateers. Among conspicuously successful cruisers, also, the United States ships "Argus," "Essex," "Peacock," and "Wasp" compare favorably in general results with the most celebrated privateers, even without allowing for the evident fact that a few instances of very extraordinary qualities and record are more likely to be found among five hundred vessels than among twenty-two; this being the entire number of naval pendants actually engaged in open-sea cruising, from first to last. These twenty-two captured one hundred and sixty-five prizes, an average of 7.5 each, in which are included the enemy's ships of war taken. Of privateers of all classes there were five hundred and twenty-six; or, excluding a few small nondescripts, four hundred and ninety-two. By these were captured thirteen hundred and forty-four vessels, an average of less than three; to be exact, 2.7. The proportion, therefore, of prizes taken by ships of war to those by private armed vessels was nearly three to one.

Comparison may be instituted in other ways. Of the twenty-two national cruisers, four only, or one in five, took no prize; leaving to the remaining eighteen an average of nine. Out of the grand total of five hundred and twenty-six privateers only two hundred and seven caught anything; three hundred and nineteen, three out of five, returned to port empty-handed, or were themselves taken. Dividing the thirteen hundred and forty-four prizes among the two hundred and seven more or less successful privateers, there results an average of 6.5; so that, regard being had only to successful cruisers, the achievement of the naval vessels was to that of the private armed nearly as three to two. These results may be accepted as disposing entirely of the extravagant claims made for privateering as a system, when compared with a regular naval service, especially when it is remembered with what difficulty the American frigates could get to sea at all, on account of their heavy draft and the close blockade; whereas the smaller vessels, national or private, had not only many harbors open, but also comparatively numerous opportunities to escape. The frigate "United States" never got out after her capture of the "Macedonian," in 1812; the "Congress" was shut up after her return in December, 1813; and the "Chesapeake" had been captured in the previous June. All these nevertheless count in the twenty-two pendants reckoned above.

The figures here cited are from a compilation by Lieutenant George F. Emmons,240 of the United States Navy, published in 1853 under the title, "The United States Navy from 1775 to 1853." Mr. Emmons made no analyses, confining himself to giving lists and particulars; his work is purely statistical. Counting captures upon the lakes, and a few along the coast difficult of classification, his grand total of floating craft taken from the enemy reaches fifteen hundred and ninety-nine; which agrees nearly with the sixteen hundred and thirty-four of Niles, whom he names among his sources of information. From an examination of the tables some other details of interest may be drawn. Of the five hundred and twenty-six privateers and letters-of-marque given by name, twenty-six were ships, sixty-seven brigs, three hundred and sixty-four schooners, thirty-five sloops, thirty-four miscellaneous; down to, and including, a few boats putting out from the beach. The number captured by the enemy was one hundred and forty-eight, or twenty-eight per cent. The navy suffered more severely. Of the twenty-two vessels reckoned above, twelve were taken, or destroyed to keep them out of an enemy's hands; over fifty per cent. Of the twelve, six were small brigs, corresponding in size and nautical powers to the privateer. Three were frigates—the "President," "Essex," and "Chesapeake." One, the "Adams," was not at sea when destroyed by her own captain to escape capture. Only two sloops of war, the first "Wasp" and the "Frolic,"241 were taken; and of these the former, as already known, was caught when partially dismasted, at the end of a successful engagement.

Contemporary with the career of the "Argus," the advantage of a sudden and unexpected inroad, like hers, upon a region deemed safe by the enemy, was receiving confirmation in the remote Pacific by the cruise of the frigate "Essex." This vessel, which had formed part of Commodore Bainbridge's squadron at the close of 1812, was last mentioned as keeping her Christmas off Cape Frio,242 on the coast of Brazil, awaiting there the coming of the consorts whom she never succeeded in joining. Captain Porter maintained this station, hearing frequently about Bainbridge by vessels from Bahia, until January 12, 1813. Then a threatened shortness of provisions, and rumors of enemy's ships in the neighborhood, especially of the seventy-four "Montagu" combined to send him to St. Catherine's Island, another appointed rendezvous, and the last upon the coast of Brazil. In this remote and sequestered anchorage hostile cruisers would scarcely look for him, at least until more likely positions had been carefully examined.

At St. Catherine's Porter heard of the action between the "Constitution" and "Java" off Bahia, a thousand miles distant, and received also a rumor, which seemed probable enough, that the third ship of the division, the "Hornet," had been captured by the "Montagu." He consequently left port January 26, for the southward, still with the expectation of ultimately joining the Commodore off St. Helena, the last indicated point of assembly; but having been unable to renew his stores in St. Catherine's, and ascertaining that there was no hope of better success at Buenos Ayres, or the other Spanish settlements within the River La Plata, he after reflection decided to cut loose from the squadron and go alone to the Pacific. There he could reasonably hope to support himself by the whalers of the enemy; that class of vessel being always well provided for long absences. This alternative course he knew would be acceptable to the Government, as well as to his immediate commander.243 The next six weeks were spent in the tempestuous passage round Cape Horn, the ship's company living on half-allowance of provisions; but on March 14, 1813, the "Essex" anchored in Valparaiso, being the first United States ship of war to show the national flag in the Pacific. By a noteworthy coincidence she had already been the first to carry it beyond the Cape of Good Hope.

Chile received the frigate hospitably, being at the time in revolt against Spain; but the authority of the mother country was still maintained in Peru, where a Spanish viceroy resided, and it was learned that in the capacity of ally of Great Britain he intended to fit out privateers against American whalers, of which there were many in these seas. As several of the British whalers carried letters-of-marque, empowering them to make prizes, the arrival of the "Essex" not only menaced the hostile interests, but promised to protect her own countrymen from a double danger. Her departure therefore was hastened; and having secured abundant provision, such as the port supplied, she sailed for the northward a week after anchoring. A privateer from Peru was met, which had seized two Americans. Porter threw overboard her guns and ammunition, and then released her with a note for the viceroy, which served both as a respectful explanation and a warning. One of the prizes taken by this marauder was recaptured March 27, when entering Callao, the port of Lima.

The "Essex" then went to the Galapagos Islands, a group just south of the equator, five hundred miles from the South American mainland. These belong now to Ecuador, and at that day were a noted rendezvous for whalers. In this neighborhood the frigate remained from April 17 to October 3, during which period she captured twelve British whalers out of some twenty-odd reported in the Pacific; with the necessary consequence of driving all others to cover for the time being. The prizes were valuable, some more, some less; not only from the character of their cargoes, but because they themselves were larger than the average merchant ship, and exceptionally well found. Three were sent to Valparaiso in convoy of a fourth, which had been converted into a consort of the "Essex," under the name of the "Essex Junior," mounting twenty very light guns. September 30 she returned, bringing word that a British squadron, consisting of the 36-gun frigate "Phœbe," Captain James Hillyar, and the sloops of war "Cherub" and "Raccoon," had sailed for the Pacific. The rumor was correct, though long antedating the arrival of the vessels. In consequence of it, Porter, considering that his work at the Galapagos was now complete, and that the "Essex" would need overhauling before a possible encounter with a division, the largest unit of which was superior to her in class and force, decided to move to a position then even more remote from disturbance than St. Catherine's had been. On October 25 the "Essex" and "Essex Junior" anchored at the island of Nukahiva, of the Marquesas group, having with them three of the prizes. Of the others, besides those now at Valparaiso, two had been given up to prisoners to convey them to England, and three had been sent to the United States. That all the last were captured on the way detracts nothing from Porter's merit, but testifies vividly to the British command of the sea.

At the Marquesas, by aid of the resources of the prizes, the frigate was thoroughly overhauled, refitted, and provisioned for six months. Porter had not only maintained his ship, but in part paid his officers and crew from the proceeds of his captures. On December 12 he sailed for Chile, satisfied with the material outcome of his venturous cruise, but wishing to add to it something of further distinction by an encounter with Hillyar, if obtainable on terms approaching equality. With this object the ship's company were diligently exercised at the guns and small arms during the passage, which lasted nearly eight weeks; the Chilean coast being sighted on January 12, far to the southward, and the "Essex" running slowly along it until February 3, when she reached Valparaiso. On the 8th the "Phœbe" and "Cherub" came in and anchored; the "Raccoon" having gone on to the North Pacific.

The antagonists now lay near one another, under the restraint of a neutral port, for several days, during which some social intercourse took place between the officers; the two captains renewing an acquaintance made years before in the Mediterranean. After a period of refit, and of repose for the crews, the British left the bay, and cruised off the port. The "Essex" and "Essex Junior" remained at anchor, imprisoned by a force too superior to be encountered without some modifying circumstances of advantage. Porter found opportunities for contrasting the speed of the two frigates, and convinced himself that the "Essex" was on that score superior; but the respective armaments introduced very important tactical considerations, which might, and in the result did, prove decisive. The "Essex" originally had been a 12-pounder frigate, classed as of thirty-two guns; but her battery now was forty 32-pounder carronades and six long twelves. Captain Porter in his report of the battle stated the armament of the "Phœbe" to be thirty long 18-pounders and sixteen 32-pounder carronades. The British naval historian James gives her twenty-six long eighteens, fourteen 32-pounder carronades, and four long nines; while to the "Cherub" he attributes a carronade battery of eighteen thirty-twos and six eighteens, with two long sixes. Whichever enumeration be accepted, the broadside of the "Essex" within carronade range considerably outweighed that of the "Phœbe" alone, but was much less than that of the two British ships combined; the light built and light-armed "Essex Junior" not being of account to either side. There remained always the serious chance that, even if the "Phœbe" accepted single combat, some accident of wind might prevent the "Essex" reaching her before being disabled by her long guns. Hillyar, moreover, was an old disciple of Nelson, fully imbued with the teaching that achievement of success, not personal glory, must dictate action; and, having a well established reputation for courage and conduct, he did not intend to leave anything to the chances of fortune incident to engagement between equals. He would accept no provocation to fight apart from the "Cherub."

Forced to accept this condition, Porter now turned his attention to escape. Valparaiso Bay is an open roadstead, facing north. The high ground above the anchorage provides shelter from the south-southwest wind, which prevails along this coast throughout the year with very rare intermissions. At times, as is common under high land, it blows furiously in gusts. The British vessels underway kept their station close to the extreme western point of the bay, to prevent the "Essex" from passing to southward of them, and so gaining the advantage of the wind, which might entail a prolonged chase and enable her, if not to distance pursuit, at least to draw the "Phœbe" out of support of the "Cherub." Porter's aim of course was to seize an opportunity when by neglect, or unavoidably, they had left a practicable opening between them and the point. In the end, his hand was forced by an accident.

On March 28 the south wind blew with unusual violence, and the "Essex" parted one of her cables. The other anchor failed to hold when the strain came upon it, and the ship began to drift to sea. The cable was cut and sail made at once; for though the enemy were too nearly in their station to have warranted the attempt to leave under ordinary conditions, Porter, in the emergency thus suddenly thrust upon him, thought he saw a prospect of passing to windward. The "Essex" therefore was hauled close to the wind under single-reefed topsails, heading to the westward; but just as she came under the point of the bay a heavy squall carried away the maintopmast. The loss of this spar hopelessly crippled her, and made it impossible even to regain the anchorage left. She therefore put about, and ran eastward until within pistol-shot of the coast, about three miles north of the city. Here she anchored, well within neutral waters; Hillyar's report stating that she was "so near shore as to preclude the possibility of passing ahead of her without risk to his Majesty's ships." Three miles, then the range of a cannon-shot, estimated liberally, was commonly accepted as the width of water adjacent to neutral territory, which was under the neutral protection. The British captain decided nevertheless to attack.

The wind remaining southerly, the "Essex" rode head to it; the two hostile vessels approaching with the intention of running north of her, close under her stern. The wind, however, forced them off as they drew near; and their first attack, beginning about 4 P.M. and lasting ten minutes, produced no visible effect, according to Hillyar's report. Porter states, on the contrary, that considerable injury was done to the "Essex"; and in particular the spring which he was trying to get on the cable was thrice shot away, thus preventing the bringing of her broadside to bear as required. The "Phœbe" and her consort then wore, which increased their distance, and stood out again to sea. While doing this they threw a few "random shots;" fired, that is, at an elevation so great as to be incompatible with certainty of aim. During this cannonade the "Essex," with three 12-pounders run out of her stern ports, had deprived the "Phœbe" of "the use of her mainsail, jib and mainstay." On standing in again Hillyar prepared to anchor, but ordered the "Cherub" to keep underway, choosing a position whence she could most annoy their opponent.

At 5.35 P.M., by Hillyar's report,—Porter is silent as to the hour,—the attack was renewed; the British ships both placing themselves on the starboard—seaward—quarter of the "Essex." Before the "Phœbe" reached the position in which she intended to anchor, the "Essex" was seen to be underway. Hillyar could only suppose that her cable had been severed by a shot; but Porter states that under the galling fire to which she was subjected, without power to reply, he cut the cable, hoping, as the enemy were to leeward, he might bring the ship into close action, and perhaps even board the "Phœbe." The decision was right, but under the conditions a counsel of desperation; for sheets, tacks, and halliards being shot away, movement depended upon sails hanging loose,—spread, but not set. Nevertheless, he was able for a short time to near the enemy, and both accounts agree that hereupon ensued the heat of the combat; "a serious conflict," to use Hillyar's words, to which corresponds Porter's statement that "the firing on both sides was now tremendous." The "Phœbe," however, was handled, very properly, to utilize to the full the tactical advantages she possessed in the greater range of her guns, and in power of manœuvring. In the circumstances under which she was acting, the sail power left her was amply sufficient; having simply to keep drawing to leeward, maintaining from her opponent a distance at which his guns were useless and her own effective.

Under these conditions, seeing success to be out of the question, and suffering great loss of men, Porter turned to the last resort of the vanquished, to destroy the vessel and to save the crew from captivity. The "Essex" was pointed for the shore; but when within a couple of hundred yards the wind, which had so far favored her approach, shifted ahead. Still clinging to every chance, a kedge with a hawser was let go, to hold her where she was; perhaps the enemy might drift unwittingly out of range. But the hawser parted, and with it the frigate's last hold upon the country which she had honored by an heroic defence. Porter then authorized any who might wish to swim ashore to do so; the flag being kept flying to warrant a proceeding which after formal surrender would be a breach of faith. At 6.20 the "Essex" at last lowered her colors.244 Out of a ship's company of two hundred and fifty-five, with which she sailed in the morning, fifty-eight were killed, or died of their wounds, and sixty-five were wounded. The missing were reported at thirty-one. By agreement between Hillyar and Porter, the "Essex Junior" was disarmed, and neutralized, to convey to the United States, as paroled prisoners of war, the survivors who remained on board at the moment of surrender. These numbered one hundred and thirty-two. It is an interesting particular, linking those early days of the United States navy to a long subsequent period of renown, and worthy therefore to be recalled, that among the combatants of the "Essex" was Midshipman David G. Farragut, then thirteen years old. His name figures among the wounded, as well as in the list of passengers on board the "Essex Junior."