полная версия

полная версияThe Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 14, No. 392, October 3, 1829

He who loves to scatter crumbs of comfort in these starving times, will not despair at this sublime truth, but will seek to cherish the love of liberty, or the consolation for the loss of it wherever he goes.

The reader need not be told that we are friends to the spread of liberty: indeed, we think she may "triumph over time, clip his wings, pare his nails, file his teeth, turn back his hour-glass, blunt his scythe, and draw the hobnails out of his shoes;" but to show how this may be done, we must run over a few varieties of liberty for the benefit of such as do not enjoy the inestimable blessings of being free and easy: we quote these words, vulgar as they are; for, of all words in our vernacular tongue, to express comfort and security from ill, commend us to the expletive of free and easy. We had rather not meddle with civil or religious liberty: they are as combustible as the Cotopaxi, or the new governments, of South America; and our attempts at reformation do not extend beyond paper and print, which the unamused reader may burn or not, as he pleases without searing his own conscience or exciting our revenge. To be sure, a few of our examples may border on civil liberty; but we shall not seek to find parallels for the Ptolemaian cages, or the Tower of Famine, in our times; neither shall we feast upon the horrors of the French Revolution, nor the last polite reception of the Russians by headless Turks; notwithstanding all these examples would bear us out in our idea of the love of liberty, and the evils of the loss of it.

Kings often want liberty, even amidst the multitude of their luxuries. They are not unfrequently the veriest slaves at court, and liege and loyal as we are, we seldom hear of a king eating, drinking, and sleeping as other people do, without envying him so happy an interval from the cares of state, and the painted pomp of palaces. This it is that makes the domestic habits of kings so interesting to every one; and many a time have we crossed field after field to catch a glimpse of royalty, in a plain green chariot on the Brighton road, when we would not have put our heads out of window to see a procession to the House of Lords. Some kings have even gone so far in their love of plain life as to drop the king, which is a very pleasant sort of unkingship. Frederick the Great, at one of his literary entertainments adopted this plan to promote free conversation, when he reminded the circle that there was no monarch present, and that every one might think aloud. The conversation soon turned upon the faults of different governments and rulers, and general censures were passing from mouth to mouth pretty freely, when Frederick suddenly stayed the topic, by saying, "Peace, peace, gentlemen, have a care, the king is coming; it may be as well if he does not hear you, lest he should be obliged to be still worse than you." Our Second Charles was very fond of liberty, and of dropping the king, or as some writers say, he never took the office up: this was for another purpose, in times when

License they mean when they cry liberty.Voluntarily parting with one's liberty is, however, very different to having it taken from us, as in the anecdote of the citizen who never having been out of his native place during his lifetime, was, for some offence, sentenced to stay within the walls a whole year; when he died of grief not long afterwards.

State imprisonment is like a set of silken fetters for kings and other great people. Thus, almost all our palaces have been used as prisons, according to the caprice of the monarch, or the violence of the uppermost faction. Shakspeare, in his historical plays, gives us many pictures of royal and noble suffering from the loss of liberty. One of the latter, with a beautiful antidote, is the address of Gaunt to Bolingbroke, after his banishment by Richard II.:—

All places that the eye of heaven visits,Are to a wise man ports, and happy havens:Teach thy necessity to reason thus:There is no virtue like necessity.Think not, the king did banish thee;But thou the king: woe doth heavier sit,Where it perceives it is but faintly borne.Go, say—I sent thee forth to purchase honour,And not—the king exiled thee: or suppose,Devouring pestilence hangs in our air,And thou art flying to a fresher clime.Look, what thy soul holds dear, imagine itTo lie that way thou go'st, not whence thou comest:Suppose the singing birds musicians;The grass whereon thou tread'st, the presence strew'd;The flowers, fair ladies; and thy steps, no moreThan a delightful measure, or a dance;For gnarling sorrow hath less power to biteThe man that mocks at it, and sets it light.Even Napoleon, whose wounds were almost green at his death, sought to chase away the recollections of his ill-starred splendour, by rides and walks in the island, and conversation with his suite in his garden; and Louis XVIII. after his restoration to the throne of France, passed few such happy days as his exile at Hartwell, which though only a pleasant seat enough, had more comfort than the gilded saloons of Versailles, or the hurly-burly of the Tuilleries, with treason hatching in the street beneath the windows, and revolution stinking in the very nostrils of the court. Shakspeare might well call a crown a

Polished perturbation! golden care!and add—

O majesty!When thou dost pinch thy bearer, thou dost sitLike a rich armour worn in heat of day,That scalds with safety.Goldsmith has somewhat sarcastically lamented that the appetites of the rich do not increase with their wealth; in like manner, it would be a grievous thing could liberty be monopolized or scraped into heaps like wealth; a petty tyrant may persecute and imprison thousands, but he cannot thereby add one hour or inch to his own liberty.

Another and a very common loss of liberty is by pleasure and the love of fame, especially by the slaves of fashion and the lovers of great place;

Whose lives are others' not their own.Pleasure for the most part, consists in fits of anticipation; since, the extra liberty or license of a debauch must be repaid by the iron fetters of headache, and the heavy hand of ennui on the following day: even the purblind puppy of fashion will tell you, if you make free with your constitution, you must suffer for it; and this by a species of slavery. To dance attendance upon a great man for a small appointment, and to boo your way through the world, belongs to the worst of servitude. Congreve compares a levee at a great man's to a list of duns; and Shenstone still more ill-naturedly says, "a courtier's dependant is a beggar's dog."

Making free, or taking liberties with your fortune, brings about the slavery, if not the sin, of poverty; and to take a liberty with the wealth of another is about as sure a road to slavery as picking pockets is to house-breaking. Debt is another of those odious badges which mark a man as a slave, and let him but go on to recovery, that like a snake in the sunshine, he may be the more effectually scotched and secured. Gay says to Swift, "I hate to be in debt; for I can't bear to pawn five pounds worth of my liberty to a tailor or a butcher. I grant you, this is not having the true spirit of modern nobility; but it is hard to cure the prejudice of education;" and every man will own that a greater slave-master is not to be found at Cape Coast than the law's follower, who says, "I 'rest you;" and then "brings you to all manner of unrest." One of these fellows is even greater than the sultan of an African tribe in till his glory; though he neither bears the insignia of rank nor power—none of the little finery which wins allegiance and honour—yet he constrains you "by virtue," and brings about a compromise and temporary cessation of your liberty.

Taking liberties with the pockets or tables of one's relations and friends, is at best, but a dangerous experiment. It cannot last long before they beg to be excused the liberty, &c., and like the countryman with the golden goose, you get a cold, fireless parlour, or a colder hall reception for your importunity; and, perchance, the silver ore being all gone, you must put up with the French plate. One of the most equivocal, if not dangerous, forms of correspondence is that beginning with "I take the liberty;" for it either portends some well tried "sufferer" as Lord Foppington calls him; a pressing call from a fundless charity; or at best but a note from an advertising tailor to tell you that for several years past you have been paying 50 per cent. too high a price for your clothes; but, like most good news, this comes upon crutches, and the loss is past redemption.

What is called the liberty of the subject we must leave for a dull barrister to explain: in the meantime, if any reader be impatient for the definition, a night's billeting in Covent Garden watchhouse will initiate him into its blessings; he is not so dull as to require to be told how to get there. The liberty of the press is another ticklish subject to handle— like a hedgehog—all points; but we may be allowed to quote, as one of the most harmless specimens of the liberty of the press—the production of THE MIRROR, as we always acknowledge the liberty by reference to the sources whence our borrowed wealth is taken. This is giving credit in one way, and taking credit for our own honesty.

Liberty-boys and brawlers would be new acquaintance for us. We are not old enough to remember "Wilkes and 45;" the cap of liberty is now seldom introduced into our national arms, and this and all such emblems are fast fading away. People who used to spout forth Cowper's line and a half on liberty, have given up the profession, and all men are at liberty to think as they please. Still ours is neither the golden nor the silver age of liberty: it is more like paper and platina liberty, things which have the weight and semblance without their value.

The only odd rencontre we ever had with a liberty advocate was with L'Abbe Gregoire, one of the cabinet advisers of Napoleon, and to judge by his writings, a benevolent man. On visiting him at Paris, we put into our pocket a little work of our leisure, containing upwards of 6,000 quotations on almost every subject. The Abbé, who understands English well, was delighted with the variety, and on calling again in a few days, we found the venerable patriot had been searching for all the passages on liberty, which he had distinguished by registers: what an evidence is this of his ruling passion. At the time we did not recollect that to M. Gregoire is attributed the republican sentiment "the reign of Kings is the martyrology of nations:" his conversation proved him an enthusiast, but we think this liberty rather too strong.

PHILO.REVENGE

'Twas lordly hate that rul'dIndomitable. 'Twas a thirst that naughtBut blood of him who broke this aching heartCould quench.'—therefore I struck–.CYMBELINETHE NATURALIST

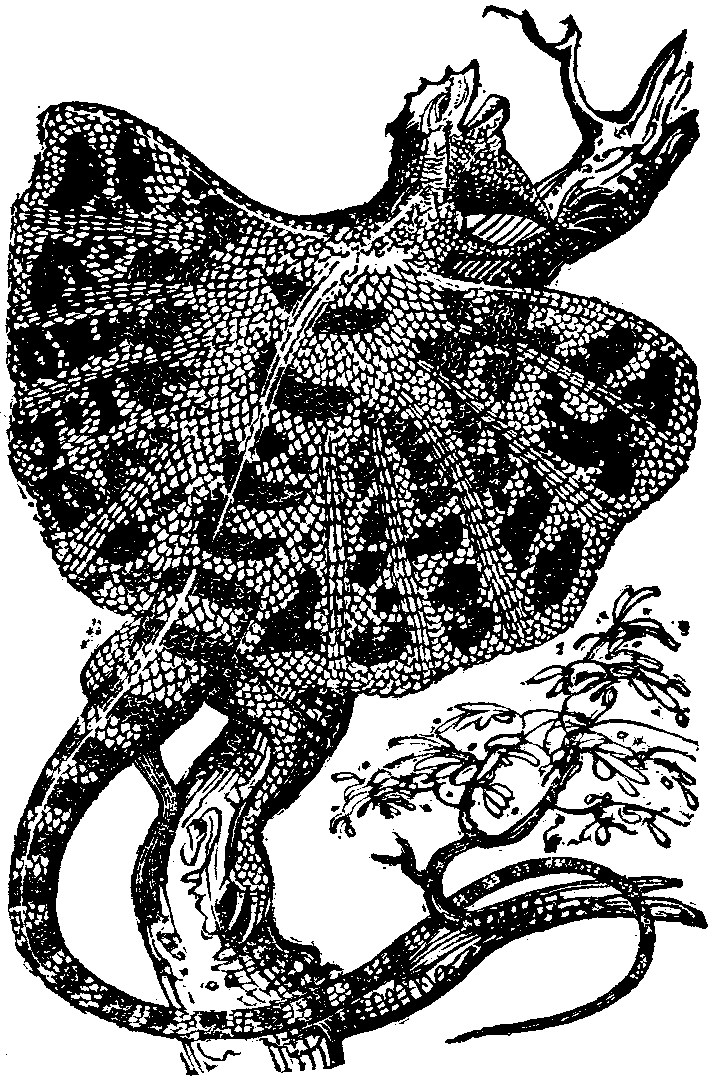

THE FLYING DRAGON

This beautiful species of the lizard tribe was one of the wonders of our ancestors, who believed it to be a fierce animal with wings, and whose bite was mortal; whereas, it is perfectly harmless, and differs from other lizards merely in its being furnished with an expanding membrane or web, strengthened by a few radii, or small bones. It is about twelve inches in length, and is found in the East Indies and Africa (Blumenbach), where it flies through short distances, from tree to tree, and subsists on flies, ants, and other insects. It is covered with very small scales, and is generally of ash-colour, varied and clouded on the back, &c. with brown, black, and white. The head is of a very singular form, and furnished with a triple pouch, under and on each side the throat.

Barbarous nations have many fabulous stories of this little animal. They say, for instance, that, although it usually lives in the water, it often bounds up from the surface, and alights on the branch of some adjacent tree, where it makes a noise resembling the laughter of a man.

The curious reader who is anxious to see a specimen of the Flying Dragon, will be gratified with a young one, preserved in a case with two Cameleons, and exposed for sale in the window of a dealer in articles of vertu, in St. Martin's Court, Leicester Square.

COCHINEAL TRANSPLANTED TO JAVA

The success with which the cultivation of the nopal and the breeding of the insect which produces cochineal has been practised at Cadiz, and thence at Malta, is well known. A French apothecary is said to have made the experiment in Corsica, but on a very confined scale; and the King of the Netherlands, on information that the Isle of Java was well adapted for the cultivation of this important article of merchandize, determined on attempting the transplantation into that colony. As the exportation of the trees and of the insect is prohibited by the laws of Spain, some management was requisite to acquire the means of forming this new establishment. The following were those resorted to:—His Majesty sent to Cadiz, and there maintained, for nearly two years, one of his subjects, a very intelligent person, who introduced himself, and by degrees got initiated into the Garden of Acclimation of the Economic Society, where the breeding of this important insect is carried on. He so well, fulfilled his commission (for which the instructions, it is said, were drawn up by his royal master himself), that he succeeded in procuring about one thousand nopals, all young and vigorous, besides a considerable number of insects; and, moreover, carried on his plans so ably, as to persuade the principal gardener of the Garden of Acclimation to enter for six years into the service of the King of the Netherlands, and to go to Batavia. Between eight and ten thousand Spanish dollars are said to have been the lure held out to him to desert his post. In the service of the Society he gained three shillings a day, paid in Spanish fashion, that is, half, at least, in arrear. A vessel of war was sent to bring away the precious cargo, which, being furtively and safely shipped, the gardener and the insects were on their voyage to Batavia before the least suspicion of what was going on was entertained by the Society.—From the French.

BEES' NESTS

A French journal says, in the woods of Brazil is frequently found hanging from the branches the nest of a species of bee, formed of clay, and about two feet in diameter. It is more probable that these nests belong to some species of wasp, many of which construct hanging nests. One sort of these is very common in the northern parts of Britain, though it is not often found south of Yorkshire.

SPIRIT OF THE PUBLIC JOURNALS

ASSASSINATION OF MAJOR LAING

The Literary Gazette of Saturday last contains the following very interesting intelligence respecting the assassination of Major Laing, and the existence of his Journal;—"In giving this tragical and disgraceful story to the British public, (says the Editor), we may notice that the individual who figures so suspiciously in it, viz. Hassouna d'Ghies, must be well remembered a few years ago in London society. We were acquainted with him during his residence here, and often met him, both at public entertainments and at private parties, where his Turkish dress made him conspicuous. He was an intelligent man, and addicted to literary pursuits; in manners more polished than almost any of his countrymen whom we ever knew, and apparently of a gentler disposition than the accusation of having instigated this infamous murder would fix upon him."

The account then proceeds with the following translation from a Marseilles Journal:—

It was about three years ago, that Major Laing, son-in-law of Colonel Hammer Warrington, consul-general of England in Tripoli, quitted that city, where he left his young wife, and penetrated into the mysterious continent of Africa, the grave of so many illustrious travellers. After having crossed the chain of Mount Atlas, the country of Fezzan, the desert of Lempta, the Sahara, and the kingdom of Ahades, he arrived at the city of Timbuctoo, the discovery of which has been so long desired by the learned world. Major Laing, by entering Timbuctoo, had gained the reward of 3,000l. sterling, which a learned and generous society in London had promised to the intrepid adventurer who should first visit the great African city, situated between the Nile of the Negroes and the river Gambaron. But Major Laing attached much less value to the gaining of the reward than to the fame acquired after so many fatigues and dangers. He had collected on his journey valuable information in all branches of science: having fixed his abode at Timbuctoo, he had composed the journal of his travels, and was preparing to return to Tripoli, when he was attacked by Africans, who undoubtedly were watching for him in the desert. Laing, who had but a weak escort, defended himself with heroic courage: he had at heart the preservation of his labours and his glory. But in this engagement he lost his right hand, which was struck off by the blow of a yatagan. It is impossible to help being moved with pity at the idea of the unfortunate traveller, stretched upon the sand, writing painfully with his left hand to his young wife, the mournful account of the combat. Nothing can be so affecting as this letter, written in stiff characters, by unsteady fingers, and all soiled with dust and blood. This misfortune was only the prelude to one far greater. Not long afterwards, some people of Ghadames, who had formed part of the Major's escort, arrived at Tripoli, and informed Colonel Warrington that his relation had been assassinated in the desert. Colonel Warrington could not confine himself to giving barren tears to the memory of his son-in-law. The interest of his glory, the honour of England, the affection of a father—all made it his duty to seek after the authors of the murder, and endeavour to discover what had become of the papers of the victim. An uncertain report was soon spread that the papers of Major Laing had been brought to Tripoli by people of Ghadames; and that a Turk, named Hassouna Dghies, had mysteriously received them. This is the same Dghies whom we have seen at Marseilles, displaying so much luxury and folly, offering to the ladies his perfumes and his shawls— a sort of travelling Usbeck, without his philosophy and his wit. From Marseilles he went to London, overwhelmed with debts, projecting new ones, and always accompanied by women and creditors. Colonel Warrington was long engaged in persevering researches, and at length succeeded in finding a clue to this horrible mystery. The Pasha, at his request, ordered the people who had made part of the Major's escort to be brought from Ghadames. The truth was at length on the point of being known; but this truth was too formidable to Hassouna Dghies for him to dare to await it, and he therefore took refuge in the abode of Mr. Coxe, the consul of the United States. The Pasha sent word to Mr. Coxe, that he recognised the inviolability of the asylum granted to Hassouna; but that the evidence of the latter being necessary in the prosecution of the proceedings relative to the assassination of Major Laing, he begged him not to favour his flight. Colonel Warrington wrote to his colleague to the same effect. However, Hassouna Dghies left Tripoli on the 9th of August, in the night, in the disguise, it is said, of an American officer, and took refuge on board the United States corvette Fairfield, Captain Parker, which was then at anchor in the roads of Tripoli. Doubtless, Captain Parker was deceived with respect to Hassouna, otherwise the noble flag of the United States would not have covered with its protection a man accused of being an accomplice in an assassination.

It is fully believed that this escape was ardently solicited by a French agent. It is even said, that the proposal was first made to the captain of one of our (French) ships, but that he nobly replied, that one of the king's officers could not favour a suspicious flight—that he would not receive Hassouna on board his ship, except by virtue of a written order, and, at all events in open day, and without disguise.

The Fairfield weighed anchor on the 10th of August, in the morning.

The Pasha, enraged at this escape of Hassouna, summoned to his palace Mohamed Dghies, brother of the fugitive, and there, in the presence of his principal officers, commanded him, with a stern voice, to declare the truth. Mohamed fell at his master's feet, and declared upon oath, and in writing, that his brother Hassouna had had Major Laing's papers in his possession, but that he had delivered them up to a person, for a deduction of forty per cent. on the debts which he had contracted in France, and the recovery of which this person was endeavouring to obtain by legal proceedings.

The declaration of Mohamed extends to three pages, containing valuable and very numerous details respecting the delivery of the papers of the unfortunate Major, and all the circumstances of this strange transaction.

The shape and size of the Major's papers are indicated with the most minute exactness; it is stated that these papers were taken from him near Timbuctoo, and subsequently delivered to the person abovementioned entire, and without breaking the seals of red wax—a circumstance which would demonstrate the participation of Hassouna in the assassination; for how can it be supposed otherwise, that the wretches who murdered the Major would have brought these packages to such a distance without having been tempted by cupidity, or even the curiosity so natural to savages, to break open their frail covers?

Mohamed, however, after he had left the palace, fearing that the Pasha in his anger would make him answerable for his brother's crime, according to the usual mode of doing justice at Tripoli, hastened to seek refuge in the house of the person of whom we have spoken, and to implore his protection. Soon afterwards the consul-general of the Netherlands, accompanied by his colleagues the consuls-general of Sweden, Denmark, and Sardinia, proceeded to the residence of the person pointed out as the receiver, and in the name of Colonel Warrington, and by virtue of the declaration of Mohamed, called upon him instantly to restore Major Laing's papers. He answered haughtily, that this declaration was only a tissue of calumnies; and Mohamed, on his side, trusting, doubtless, in a pretended inviolability, yielding, perhaps, to fallacious promises, retracted his declaration, completely disowned it, and even went so far as to deny his own hand-writing.

This recantation deceived nobody; the Pasha, in a transport of rage, sent to Mohamed his own son, Sidi Ali; this time influence was of no avail. Mohamed, threatened with being seized by the chiaoux, retracted his retractation; and in a new declaration, in the presence of all the consuls, confirmed that which he made in the morning before the Pasha and his officers.

One consolatory fact results from these afflicting details: the papers of Major Laing exist, and the learned world will rejoice at the intelligence; but in the name of humanity, in the name of science, in the name of the national honour—compromised, perhaps, by disgraceful or criminal bargains—it must be hoped that justice may fall upon the guilty, whoever he may be.

A COFFEE-ROOM CHARACTER

It was about the year 1805 that we were first ushered into the dining-house called the Cheshire Cheese, in Wine-office-court. It is known that Johnson once lodged in this court, and bought an enormous cudgel while there, to resist a threatened attack from Macpherson, the author, or editor, of Ossian's Poems. At the time we first knew the place (for its visiters and keepers are long since changed for the third or fourth time,) many came there who remembered Johnson and Goldsmith spending their evenings in the coffee-room; old half-pay officers, staid tradesmen of the neighbourhood, and the like, formed the principal portion of the company.

Few in this vast city know the alley in Fleet-street which leads to the sawdusted floor and shining tables; those tables of mahogany, parted by green-curtained seats, and bound with copper rims to turn the edge of the knife which might perchance assail them during a warm debate; John Bull having a propensity to commit such mutilations in the "torrent, tempest, and whirlwind" of argument. Thousands have never seen the homely clock that ticks over the chimney, nor the capacious, hospitable-looking fire-place under,3 both as they stood half a century ago, when Fleet-street was the emporium of literary talent, and every coffee-house was distinguished by some character of note who was regarded as the oracle of the company.