полная версия

полная версияThe Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 14, No. 392, October 3, 1829

Various

The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction / Volume 14, No. 392, October 3, 1829

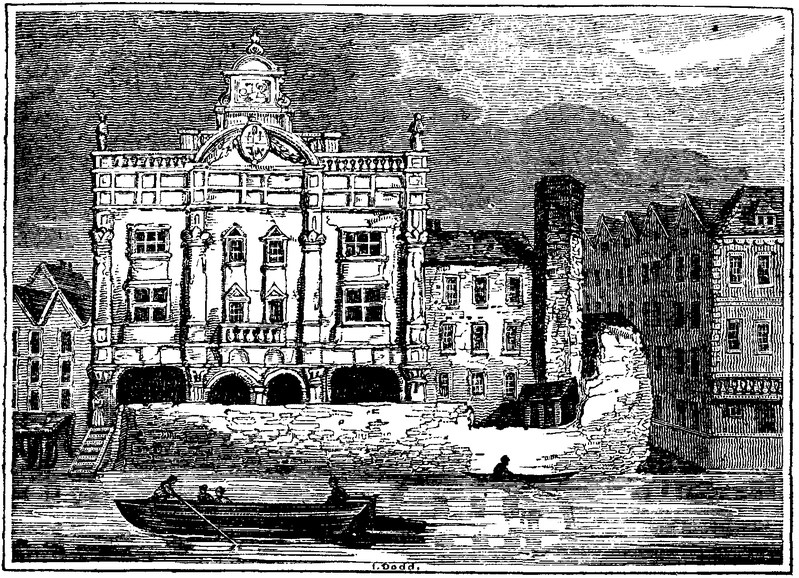

The Duke's Theatre, Dorset Gardens

The above theatre was erected in the year 1671, about a century after the regular establishment of theatres in England. It rose in what may be called the brazen age of the Drama, when the prosecutions of the Puritans had just ceased, and legitimacy and licentiousness danced into the theatre hand in hand. At the Restoration, the few players who had not fallen in the wars or died of poverty, assembled under the banner of Sir William Davenant, at the Red Bull Theatre. Rhodes, a bookseller, at the same time, fitted up the Cockpit in Drury Lane, where he formed a company of entirely new performers. This was in 1659, when Rhodes's two apprentices, Betterton and Kynaston, were the stars. These companies afterwards united, and were called the Duke's Company. About the same time, Killigrew, that eternal caterer for good things, collected together a few of the old actors who were honoured with the title of the "King's Company," or "His Majesty's Servants," which distinction is preserved by the Drury Lane Company, to the present day, and is inherited from Killigrew, who built and opened the first theatre in Drury Lane, in 1663. In 1662, Sir William Davenant obtained a patent for building "the Duke's Theatre," in Little Lincoln's Inn Fields, which he opened with the play of "the Siege of Rhodes," written by himself. The above company performed here till 1671, when another "Duke's Theatre." was built in Dorset Gardens,1 by Sir Christopher Wren, in a similar style of architecture to that in Lincoln's Inn Fields. The company removed thither, November 9, in the same year, and continued performing till the union of the Duke and the King's Companies, in 1682; and performances were continued occasionally here until 1697. The building was demolished about April, 1709, and the site is now occupied by the works of a Gas Light Company.

The Duke's Theatre, as the engraving shows, had a handsome front towards the river, with a landing-place for visiters by water, a fashion which prevailed in the early age of the Drama, if we may credit the assertion of Taylor, the water poet, that about the year 1596, the number of watermen maintained by conveying persons to the theatres on the banks of the Thames, was not less than 40,000, showing a love of the drama at that early period which is very extraordinary.2 All we have left of this aquatic rage is a solitary boat now and then skimming and scraping to Vauxhall Gardens.

The upper part of the front will be admired for its characteristic taste; as the figures of Comedy and Tragedy surmounting the balustrade, the emblematic flame, and the wreathed arms of the founder.

Operas were first introduced on the English stage, at Dorset Gardens, in 1673, with "expensive scenery;" and in Lord Orrery's play of Henry V., performed here in the year previous, the actors, Harris, Betterton, and Smith, wore the coronation suits of the Duke of York, King Charles, and Lord Oxford.

The names of Betterton and Kynaston bespeak the importance of the Duke's Theatre. Cibber calls Betterton "an actor, as Shakspeare was an author, both without competitors;" in his performance of Hamlet, he profited by the instructions of Sir William Davenant, who embodied his recollections of Joseph Taylor, instructed by SHAKSPEARE to play the character! What a delightful association—to see Hamlet represented in the true vein in which the sublime author conceived it! Kynaston's celebrity was of a more equivocal description. He played Juliet to Betterton's Romeo, and was the Siddons of his day; for women did not generally appear on the stage till after the Restoration. The anecdote of Charles II. waiting at the theatre for the stage queen to be shaved is well known.

Pepys speaks of Harris, in his interesting Diary as "growing very proud, and demanding 20l. for himself extraordinary more than Betterton, or any body else, upon every new play, and 10l. upon every revive; which, with other things, Sir William Davenant would not give him, and so he swore he would never act there more, in expectation of his being received in the other house;" (this was in 1663, at the Duke's Theatre in Lincoln's Inn Fields.) "He tells me that the fellow grew very proud of late, the King and every body else crying him up so high," &c. Poor Sir William, he must have been as much worried and vexed as Mr. Ebers with the Operatics, or any Covent Garden manager, in our time; whose days and nights are not very serene, although passed among the stars,

In one of Pepys's notices of Hart, he tells us "It pleased us mightily to see the natural affection of a poor woman, the mother of one of the children brought upon the stage; the child crying, she, by force, got upon the stage, and took up her child, and carried it away off the stage from Hart." This pleasant playgoer likewise says, in 1667-8, "when I began first to be able to bestow a play on myself, I do not remember that I saw so many by half of the ordinary prentices and mean people in the pit at 2s. 6d. a-piece as now; I going for several years no higher than the 12d. and then the 18d. places, though I strained hard to go in then when I did; so much the vanity and prodigality of the age is to be observed in this particular."

It may be at this moment interesting to mention that the first Covent Garden Theatre was opened under the patent granted to Sir William Davenant for the Dorset Gardens and Lincoln's Inn Fields Theatres. We must also acknowledge our obligation for the preceding notes to the Companion to the Theatres, a pretty little work which we noticed en passant when published, and which we now seasonably recommend to the notice of our readers.

FOUR SONNETS

SPRING

Season of sighs perfumed, and maiden flowers,Young Beauty's birthday, cradled in delightAnd kept by muses in the blushing bowersWhere snow-drops spring most delicately white!Oh it is luxury to minds that feelNow to prove truants to the giddy world,Calmly to watch the dewy tints that stealO'er opening roses—'till in smiles unfurledTheir fresh-made petals silently unfold.Or mark the springing grass—or gaze uponPrimeval morning till the hues of goldBlaze forth and centre in the glorious sun!Whose gentler beams exhale the tears of night,And bid each grateful tongue deep melodies indite.SUMMER

Now is thy fragrant garland made complete,Maturing year! but as its many dyesMingle in rainbow hues divinely sweet,They fade and fleet in unobserved sighs!Yet now all fresh and fair, how dear thou art,Just born to breathe and perish! touched by heaven,From lifeless Winter to a beating heart,From scathing blasts to Summer's balmy even!Methinks some angel from the bowers of bliss,In May descended, scattering blossoms round,Embraced each opening flower, bestowed a kiss,And woke the notes of harmony profound;But ere July had waned, alas, she fled,Took back to heaven the flowers, and left the falling leaves instead.AUTUMN

Field flowers and breathing minstrelsy, farewell!The rose is colourless and withering fast,Sweet Philomel her song forgets to swell,And Summer's rich variety is past!The sear leaves wander, and the hoar of ageGathers her trophy for the dying year,And following in her noiseless pilgrimage,Waters her couch with many a pearly tear.Yet there is one unchanging friend who staysTo cheer the passage into Winter's gloom—The redbreast chants his solitary lays,A simple requiem over Nature's tomb,So, when the Spring of life shall end with me,God of my Fathers! may I find a changeless Friend in thee!WINTER

The trees are leafless, and the hollow blastSings a shrill anthem to the bitter gloom,The lately smiling pastures are a waste,While beauty generates in Nature's womb;The frowning clouds are charged with fleecy snow,And storm and tempest bear a rival sway;Soft gurgling rivulets have ceased to flow,And beauty's garlands wither in decay:Yet look but heavenward! beautiful and youngIn life and lustre see the stars of nightUntouch'd by time through ages roll along,And clear as when at first they burst to light.And then look from the stars where heaven appearsClad in the fertile Spring of everlasting years!BENJAMIN GOUGH.EXERCISE, AIR, AND SLEEP

(Abridged from Mr. Richards's "Treatise on Nervous Disorders.")The generality of people are well aware of the vast importance of exercise; but few are acquainted with its modus operandi, and few avail themselves so fully as they might of its extensive benefits. The function of respiration, which endues the blood with its vivifying principle, is very much influenced by exercise; for our Omniscient Creator has given to our lungs the same faculty of imbibing nutriment from various kinds of air, as He has given to the stomach the power of extracting nourishment from different kinds of aliment; and as the healthy functions of the stomach depend upon the due performance of certain chemical and mechanical actions, so do the functions of the lungs depend upon the due performance of proper exercise.

Man being an animal destined for an active and useful life, Providence has ordained that sloth shall bring with it its own punishment. He who passes nearly the whole of his life in the open air, inhaling a salubrious atmosphere, enjoys health and vigour of body with tranquillity of mind, and dies at the utmost limit allotted to mortality. He, on the contrary, who leads an indolent or sedentary life, combining with it excessive mental exertion, is a martyr to a train of nervous symptoms, which are extremely annoying. Man was not created for a sedentary or slothful life; but all his organs and attributes are calculated for an existence of activity and industry. If therefore we would insure health and comfort, we must make exercise—to use Dr. Cheyne's expression—a part of our religion. But this exercise should be in the open air, and in such places as are most free from smoke, or any noxious exhalations; where, in fact, the air circulates freely, purely, and abundantly. I am continually told by persons that they take a great deal of exercise, being constantly on their feet from morning till night; but, upon inquiry, it happens, that this exercise is not in the open air, but in a crowded apartment, perhaps, as in a public office, a manufactory, or at a dress maker's, where twenty or thirty young girls are crammed together from nine o'clock in the morning till nine at night, or, what is nearly as pernicious, in a house but thinly inhabited. Exercise this cannot be called; it is the worst species of labour, entailing upon its victims numerous evils. Good air is as essential as wholesome food; for the air, by coming into immediate contact with the blood, enters at once into the constitution. If therefore the air be bad, every part of the body, whether near the heart or far from it, must participate in the evil which is produced.

It is on this account that exercise in the open air is so materially beneficial to digestion. If the blood be not properly prepared by the action of good air, how can the arteries of the stomach secrete good gastric juice? Then, we have a mechanical effect besides. By exercise the circulation of the blood is rendered more energetic and regular. Every artery, muscle, and gland is excited into action, and the work of existence goes on with spirit. The muscles press the blood-vessels, and squeeze the glands, so that none of them can be idle; so that, in short, every organ thus influenced must be in action. The consequence of all this is, that every function is well performed. The stomach digests readily, the liver pours out its bile freely, the bowels act regularly, and much superfluous heat is thrown out by perspiration. These are all very important operations, and in proportion to the perfection with which they are performed will be the health and comfort of the individual.

There is another process accomplished by exercise, which more immediately concerns the nervous system. "Many people," says Mr. Abernethy, "who are extremely irritable and hypochondriacal, and are constantly obliged to take medicines to regulate their bowels while they live an inactive life, no longer suffer from nervous irritation, or require aperient medicines when they use exercise to a degree that would be excessive in ordinary constitutions." This leads us to infer that the superfluous energy of the nerves is exhausted by the exercise of the body, and that as the abstraction of blood mitigates inflammations, in like manner does the abstraction of nervous irritability restore tranquillity to the system. This of course applies only to a state of high nervous irritation; but exercise is equally beneficial when the constitution is much weakened, by producing throughout the whole frame that energetic action which has been already explained.

A debilitated frame ought never to take so much exercise as to cause fatigue, neither ought exercise to be taken immediately before nor immediately after a full meal. Mr. Abernethy's prescription is a very good one—to rise early and use active exercise in the open air, till a slight degree of fatigue be felt; then to rest one hour, and breakfast. After this rest three hours, "in order that the energies of the constitution may be concentrated in the work of digestion;" then take active exercise again for two hours, rest one, and then dine. After dinner rest for three hours; and afterwards, in summer, take a gentle stroll, which, with an hour's rest before supper, will constitute the plan of exercise for the day. In wet or inclement weather, the exercise may be taken in the house, the windows being opened, "by walking actively backwards and forwards, as sailors do on ship-board."

We now come to the consideration of air. Pure air is as necessary to existence as good and wholesome food; perhaps more so; for our food has to undergo a very elaborate change before it is introduced into the mass of circulating blood, while the air is received at once into the lungs, and comes into immediate contact with the blood in that important organ. The effect of the air upon the blood is this: by thrusting out as it were, all the noxious properties which it has collected in its passage through the body, it endues it with the peculiar property of vitality, that is, it enables it to build up, repair, and excite the different functions and organs of the body. If therefore this air, which we inhale every instant, be not pure, the whole mass of blood is very soon contaminated, and the frame, in some part or other speedily experiences the bad effects. This will explain to us the almost miraculous benefits which are obtained by change of air, as well as the decided advantages of a free and copious ventilation. The prejudices against a free circulation of air, especially in the sick chamber, are productive of great evil. The rule as regards this is plain and simple: admit as much fresh air as you can; provided it does not blow in upon you in a stream, and provided you are not in a state of profuse perspiration at the time; for in accordance with the Spanish proverb—

"If the wind blows on you through a holeMake your will, and take care of your soul."but if the whole of the body be exposed at once to a cold atmosphere, no bad consequences need be anticipated.

A great deal has been said about the necessary quantity of sleep; that is, how long one ought to indulge in sleeping. This question, like many others, cannot be reduced to mathematical precision; for much must depend upon habit, constitution, and the nature and duration of our occupations. A person in good health, whose mental and physical occupations are not particularly laborious, will find seven or eight hours' sleep quite sufficient to refresh his frame. Those whose constitutions are debilitated, or whose occupations are studious or laborious, require rather more; but the best rule in all eases is to sleep till you are refreshed, and then get up. If you feel inclined for a snug nap after dinner, indulge in it; but do not let it exceed half an hour; if you do, you will be dull and uncomfortable afterwards, instead of brisk and lively.

In sleeping, as in eating and drinking, we must consult our habits and feelings, which are excellent monitors. What says the poet?—

"Preach not to me your musty rules,Ye drones, that mused in idle cell,The heart is wiser than the schools,The senses always reason well."One particular recommendation I would propose in concluding this subject, from the observance of which much benefit has been derived—it is to sleep in a room as large and as airy as possible, and in a bed but little encumbered with curtains. The lungs must respire during sleep, as well as at any other time; and it is of great consequence that the air should be as pure as possible. In summer curtains should not be used at all, and in winter we should do well without them. In summer every wise man, who can afford it, will sleep out of town—at any of the villages which are removed sufficiently from the smoke and impurities of this overgrown metropolis.

THE NOVELIST

AN INCIDENT AT FONDI

"Away—three cheers—on we go."The morning was delightful; neither Corregio, nor Claude, with all their magic of conception could have made it lovelier. The heaven expanded like an azure sea—and the dimpling clouds of gold were its Elysian isles—not unlike the splendid images we are apt to admire in the poems of Petrarch and Alamanni. The music of the birds kept time to the sound of the postilions' whips—the streams sung a fairy legend, and the merry woods, touched with the brilliant glow of an Italian sun, breathed into the air a delicious sonata. Such a morning as this was formed for something memorable! The Grand Diavolo and his bravest ruffians awaited the travellers' approach.

The carriage had pursued the direction of the path at a speed unequalled in the annals of the postilions; but the termination of the dell did not appear. Huge impending cliffs with their crown of trees imparted a shadowy depth to the solitude, which the travellers did not seem to relish.

"How cursed inconvenient is this dell with its frightful woods," said the baronet to his smiling daughter, "one might as well be sequestered in Dante's Inferno. Look at those awful rocks—my mind misgives me as I view them. Sure there are no brigands concealed hereabout!"

"Hope not, Pa'," replied the graceful Rosalia; but the last word had scarcely died on her lips, ere a discharge of shot was heard. The baronet opened his carriage door, and leaped on the ground.

"Hollo! John, Tom, pistols here, my lads, a pretty rencontre this! Stand by Rosalia, my own self and purse I don't value a grout, but stand the brunt, lads; here they come—oh, that I had met them at Waterloo!"

This attack perplexed the thoughts of the poor baronet. He regarded it as a romance in which he was to become the hero. But his present situation did not allow him the fascination of a dream. The brigands advanced from their concealment, and their chief, who seemed a most pleasant and polite scoundrel, commanded his men to inspect the luggage of the travellers.

"Humph! and is that all?" growled the baronet.

"I want a thousand crowns," said the chief, in a gentle tone, "you may then proceed."

"Humph! and won't five hundred do?"

"I insist!" returned the brigand, placing his hand on his sword!

This menace was enough. It produced an awful consternation in the countenance of the Englishman. He, dear man, felt his heart quake within him, as he paid the brigand his enormous demand. But a second trial was reserved for him—he turned to his carriage—his daughter was not there! where could she be? He heard a laugh, and on raising his head, saw the identical object of his care! She waved her delicate white handkerchief from the steeps above, while an Italian officer stood beside her laughing with all his might. The suspicions of the father were realized. He was the tall intriguing scamp who had charmed the eyes of Rosalia at the inn!

Away ran the sire, but the guilty pair seemed to fly with the wings of love attached to their heels; up the steep he clambered, scaring all the birds from their solitudes; still the lovers kept on before; they passed the bridge of Laino; the infuriated sire pursued; spire, tree, castle, church, stream; and in short the most beautiful features of the landscape appeared in the chase, but the fugitives did not stop to survey them. Away they pressed down the sunny slope, through the glen, along the margin of the Casparanna, swifter to the eye of the agonized parent than Jehu's chariot-wheels. Now they flag—they sit down amid the ruins of yonder old chapel—he will reach them now; alas! how vain are the calculations of man! In leaping across the Cathanna Mare, he received a shot in his arm; the cursed Italian had fired at him, and he fell, like a wounded bird into the stream!

"Dear pa', how you kick one!" exclaimed the beauteous little daughter of the Englishman; "surely you have had a troublesome dream." "Dream! let me see," said the baronet, rubbing his eyes; "then I'm not drowned, and we are again at Albano, are we, and this is our merry host, and thank God, Rosalia, you are safe, and I must kiss you, my sweet girl." This was a pleasant scene!

R. AUGUSTINE.TIME

IN IMITATION OF THE OLDEN POETS(For the Mirror.)Time is a taper waning fast!Use it, man, well whilst it doth last:Lest burning downwards it consume away,Before thou hast commenced the labour of the day.Time is a pardon of a goodly soil!Plenty shall crown thine honest toil:But if uncultivated, rankest weedsShall choke the efforts of the rising seeds.Time is a leasehold of uncertain date!Granted to thee by everlasting fate.Neglect not thou, ere thy short term expire,To save thy soul from ever-burning fire.LEAR.SEPULCHRAL ENIGMA

(To the Editor of the Mirror.)The following Sepulchral Enigma against Pride, is engraved on a stone, in the Cathedral Church of Hamburgh:

"O, Mors, cur, Deus, negat, vitam,be, se, bis, nos, his, nam."CANON

Ordine daprimam mediae? mediamqz sequenti,Debita sic nosces fala, superbe, tibi.Quid mortalis homo jactas tot quidve superbis?Cras forsan fies, pulvis et umbra levis,Quid tibi opes prosunt? Quid nuuc tibi magna potesias?Quidve honor? Ant praestans quid tibi forma? Nihil.Vide Variorum in Europa itinerum deliciae, &c.Nathane Chitreo, Editio Secunda, 1599.The above inscription and Canon are from a very scarce book, me penes; if they are deemed worthy of a place in your entertaining miscellany, and no solution or English version should be offered to your notice for insertion, I will avail myself of your permission to send one for your approval.

Your's, &c. Σ [Greek: S.]THE VINE—A FRAGMENT

(For the Mirror.)See o'er the wall, the white-leav'd cluster-vineShoots its redundant tendrils; and doth seem,Like the untam'd enthusiast's glowing heart,Ready to clasp, with an abundant love,All nature in its arms!C. COLE.THE COSMOPOLITE

ON LIBERTY

"I don't hate the world, but I laugh at it;for none but fools can be in earnest about a trifle."So says Gay of the world, in one of his letters to Swift, and we have adapted the quotation to our idea of liberty. True it is that Addison apostrophizes liberty as a

Goddess, heavenly bright!but we hope our laughter will not be considered as indecorous or profane. Our great essayist has exalted her into a Deity, and invested her with a mythological charm, which makes us doubt her existence; so that to laugh at her can be no more irreverend than to sneer at the belief in apparitions, a joke which is very generally enjoyed in these good days of spick-and-span philosophy. Whether Liberty ever existed or not, is to us a matter of little import, since it is certain that she belongs to the grand hoax which is the whole scheme of life. The extension of liberty into concerns of every-day life is therefore reasonable enough, and to prove that we are happy in possessing this ideal blessing, seems to have been the aim of all who have written on the subject. One, however, if we remember right, sets the matter in a grave light, when he says to man—