полная версия

полная версияThe Battle of the Marne

Instead of an initial defensive over most of the front, with or without some carefully chosen and strongly provided manœuvre of offence—as the major conditions of the problem would seem to suggest—the French campaign opened with a general offensive, which for convenience we must divide into three parts, three adventures, all abortive, into Southern Alsace, German Lorraine, and the Belgian Ardennes. The first two of these were predetermined, even before General Joffre was designed for the chief command; the second and third were deliberately launched after the invasion of Belgium was, or should have been, understood. A fourth attack, across the Sambre, was designed, but could not be attempted.

The first movement into Alsace was hardly more than a raid, politically inspired, and its success might have excited suspicions. Advancing from Belfort, the 1st Army under Dubail took Altkirch on August 7, and Mulhouse the following day. Paris rejoiced; General Joffre hailed Dubail’s men as “first labourers in the great work of la revanche.” It was the last flicker of the old Gallic cocksureness. On August 9, the Germans recovered Mulhouse. Next day, an Army of Alsace, consisting of the 7th Corps, the 44th Division, four reserve divisions, five Alpine battalions, and a cavalry division, was organised under General Pau. It gained most of the Vosges passes and the northern buttress of the range, the Donon (August 14). On the 19th, the enemy was defeated at Dornach, losing 3000 prisoners and 24 cannon; and on the following morning Mulhouse was retaken—only to be abandoned a second time on the 25th, with all but the southern passes. The Army of Alsace was then dissolved to free Pau’s troops for more urgent service, the defence of Nancy and of Paris.

The Lorraine offensive was a more serious affair, and it was embarked upon after the gravity of the northern menace had been recognised.17 The main body of the Eastern forces was engaged—nine active corps of the 2nd and 1st Armies, with nine reserve and three cavalry divisions—considerably more than 400,000 men, under some of the most distinguished French generals, including de Castlenau, unsurpassed in repute and experience even by the Generalissimo himself; Dubail, a younger man, full of energy and quick intelligence; Foch, under whose iron will the famous 20th Corps of Nancy did much to limit the general misfortune; Pau, who had just missed the chief command; and de Maud’huy, a sturdy leader of men. As soon as the Vosges passes were secured, after ten days’ hard fighting, on August 14, a concerted advance began, Castelnau moving eastward over the frontier into the valley of the Seille and the Gap of Morhange, a narrow corridor flanked by marshes and forests, rising to formidable cliffs; while Dubail, on his right, turned north-eastward into the hardly less difficult country of the Sarre valley. The French appear to have had a marked superiority of numbers, perhaps as large as 100,000 men; but they were drawn on till they fell into a powerful system, established since the mobilisation, of shrewdly hidden defences, with a large provision of heavy artillery, from Morville, through Morhange, Bensdorf, and Fenetrange, to Phalsburg—the Bavarian Army at the centre, a detachment from the Metz garrison against the French left, the army of Von Heeringen against the right. The French command can hardly have been ignorant of these defences, but must have supposed they would fall to an impetuous assault. Dubail held his own successfully throughout August 19 and 20 at Sarrebourg and along the Marne-Rhine Canal, though his men were much exhausted. Castelnau was immediately checked, before the natural fortress of Morhange, on August 20. His centre—the famous 20th Corps and a southern corps, the 15th—attacked at 5 a.m.; at 6.30 the latter was in flight, and the former, its impetuosity crushed by numbers and artillery fire, was ordered to desist. The German commanders had concentrated their forces under cover of field-works and heavy batteries. Under the shock of this surprise, at 4 p.m., Castelnau ordered the general retreat. Dubail had to follow suit.

Happily, the German infantry were in no condition for an effective pursuit, and the French retirement was not seriously impeded. The following German advance being directed southward, with the evident intention of forcing the Gap of Charmes, and so taking all the French northern armies in reverse, the defence of Nancy was left to Foch, Castelnau’s centre and right were swung round south-westward behind the Meurthe, while Dubail abandoned the Donon, and withdrew to a line which, from near Rozelieures to Badonviller and the northern Vosges, made a right-angle with the line of the 2nd Army, the junction covering the mouth of the threatened trouée. In turn, as we shall see (Chap. III. sec. iii.), the German armies here suffered defeat, only five days after their victory. But such failures and losses do not “cancel out,” for France had begun at a disadvantage. Ground was lost that might have been held with smaller forces; forces were wasted that were urgently needed in the chief field of battle. Evidently it was hoped to draw back parts of the northern armies of invasion, to interfere with their communications, and to set up an alarm for Metz and Strasbourg. These aims were not to any sensible extent accomplished.

Despite the improbability of gaining a rapid success in a wild forest region, the French Staff seems to have long cherished the idea of an offensive into the Belgian Ardennes in case of a German invasion of Belgium, the intention being to break the turning movement by a surprise blow at its flank. By August 19, the French were in a measure prepared for action between Verdun and the Belgian Meuse. Ruffey’s 3rd Army (including a shortlived “Army of Lorraine” of six reserve divisions under Maunoury), and Langle de Cary’s 4th Army, brought northwards into line after three or four days’ delay, counted together six active corps and reserve groups making them nearly equal in numbers to the eleven corps of the Imperial Crown Prince and the Duke of Würtemberg. But, behind the latter, all unknown till it debouched on the Meuse, lay hidden adroitly in Belgian Luxembourg another army, the three corps of the Saxon War Minister, Von Hausen. Farther west, the disparity of force was greater, Lanrezac and Sir John French having only about seven corps (with some help from the Belgians and a few Territorial units) against eleven corps left to Bülow and Kluck after two corps had been detailed to mask the Belgian Army in Antwerp. Neither the Ardennes nor the Sambre armies could be further strengthened because of the engagements in Lorraine and Alsace.

A tactical offensive into the Ardennes, a glorified reconnaissance and raid, strictly limited and controlled, might perhaps be justified. The advance ordered on the evening of the defeat of Morhange, and executed on the two following days, engaging the only general reserve at the outset in a thickly-wooded and most difficult country, was too large for a diversion, and not large enough for the end declared: it failed completely and immediately—in a single day, August 22—with heavy losses, especially in officers.18 Here, again, there was an approximate equality of numbers; again, the French were lured on to unfavourable ground, and, before strong entrenchments, crushed with a superiority of fire. Separated and surprised—the left south-west of Palliseul, the centre in the forests of Herbeumont and Luchy, the Colonial Corps before Neufchateau and Rossignol, where it fought literally to the death against two German corps strongly entrenched, the 2nd Corps near Virton—the body of the 4th Army was saved only by a prompt retreat; and the 3rd Army had to follow this movement. True, the German IV Army also was much exhausted; and an important part of the enemy’s plan missed fire. It had been soon discovered that the Meuse from Givet to Namur was but lightly held; and the dispatch thither of the Saxon Army, to cut in between the French 4th and 5th Armies, was a shrewd stroke. Hausen was late in reaching the critical point, about Dinant, and, by slowness and timidity, missed the chance of doing serious mischief.

Meanwhile, between the fields of the two French adventures into German Lorraine and Belgian Luxembourg, the enemy had been allowed without serious resistance to occupy the Briey region, and so to carry over from France to Germany an iron- and coal-field of the utmost value. “Briey has saved our life,” the ironmasters of the Rhineland declared later on, with some exaggeration. Had it been modernised, the small fortress of Longwy, situated above the River Chiers three miles from the Luxembourg frontier, might have been an important element in a defence of this region. In fact, its works were out of date, and were held at the mobilisation by only two battalions of infantry and a battery and a half of light guns. The Germans summoned Colonel Darche and his handful of men to surrender on August 10; but the place was not invested till the 20th, the day on which the 3rd Army was ordered to advance toward Virton and Arlon, and to disengage Longwy. Next day, Ruffey was north and east of the place, apparently without suspecting that he had the Crown Prince’s force besieging it at his mercy. On the 22nd, it was too late; the 3rd and 4th Armies were in retreat; Longwy was left to its fate.19

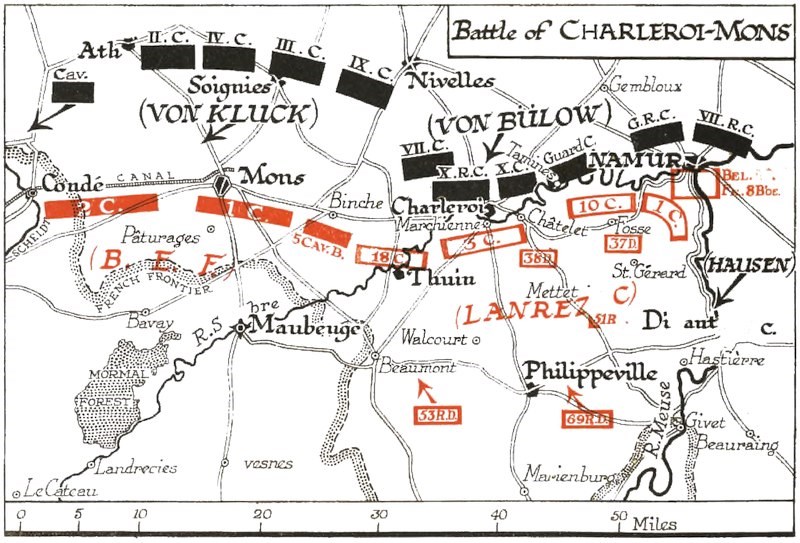

V. The Battle of Charleroi–MonsThe completest surprise naturally fell on the west wing of the Allies; and, had not the small British force been of the hardiest stuff, an irreparable disaster might have occurred. Here, with the heaviest preponderance of the enemy, there had been least preparation for any hostilities before the crisis was reached. On or about August 10, we war correspondents received an official map of the “Present Zone of the Armies,” which was shown to end, on the north, at Orchies—16 miles S.E. of Lille, and 56 miles inland from Dunkirk. The western half of the northern frontier was practically uncovered. Lille had ceased to be a fortress in 1913, though continuing to be a garrison town; from Maubeuge to the sea, there was no artificial obstacle, and no considerable body of troops.20 The position to be taken by the British Expeditionary Force—on the French left near Maubeuge—was only decided, at a Franco-British Conference in London, on August 10.21 On August 12, the British Press Bureau announced it as “evident” that “the mass of German troops lie between Liège and Luxembourg.” Three days later, a Saxon advance guard tried, without success, to force the Meuse at Dinant. Thus warned, the French command began to make the new disposition of its forces which has been alluded to.

Lanrezac had always anticipated the northern attack, and had made representations on the subject without effect.22 At last, on August 16, General Joffre, from his headquarters at Vitry-le-François, in southern Champagne, agreed to his request that he should move the 5th Army north-westward into the angle of the Sambre and Meuse. At the same time, however, its composition was radically upset, the 11th Corps and two reserve divisions being sent to the 4th Army, while the 18th Corps and the Algerian divisions were received in compensation. On August 16, the British Commander-in-Chief, after seeing President Poincaré and the Ministers in Paris, visited the Generalissimo at Vitry; and it was arranged that the Expeditionary Force, which was then gathering south of Maubeuge, should move north to the Sambre, and thence to the region of Mons. On the same day, General d’Amade was instructed to proceed from Lyons to Arras, there to gather together three Territorial divisions of the north which, reinforced by another on the 21st and by two reserve divisions on the 25th, ultimately became part of the Army of the Somme. Had there been, on the French side, any proper appreciation of the value of field-works, it might, perhaps, not have been too late to defend the line of the Sambre and Meuse. It was four or five days too late to attempt a Franco-British offensive beyond the Sambre.

To do justice to the Allied commanders, it must be kept clearly in mind that they had (albeit largely by their own fault) but the vaguest notion of what was impending. Would the mass of the enemy come by the east or the west of the Meuse, by the Ardennes or by Flanders, and in what strength? Still sceptical as to a wide enveloping movement, Joffre was reluctant to adventure too far north with his unready left wing; but it seemed to him that, in either case, the intended offensive of the French central armies (the 3rd and 4th) across the Ardennes and Luxembourg frontier might be supported by an attack by Lanrezac and the British upon the flank of the German western armies—the right flank, if they passed by the Ardennes only; the left, if they attempted to cross the Flanders plain toward the Channel. Thus, it was provisionally arranged with the British Commander that, when the concentration of the Expeditionary Force was complete, which would not be before the evening of August 21, it should advance north of the Sambre in the general direction of Nivelles (20 miles north-east of Mons, and half-way between Charleroi and Brussels). If the common movement were directed due north, the British would advance on the left of the 5th Army; if to the north-east or east, they would be in echelon on its left-rear. General Joffre recognised that the plan was only provisional, it being impossible to define the projected manœuvre more precisely till all was ready on August 21, or till the enemy revealed his intentions.

It was only on the 20th that two corps of the French 5th Army reached the south bank of the Sambre—one day before Bülow came up on the north, with his VII Corps on his right (west), the X Reserve and X Active Corps as centre, the Guard Active Corps on his left, and the VII Reserve (before Namur) and Guard Reserve Corps in support. In this posture, on the evening of August 20, Lanrezac received General Joffre’s order to strike across the Sambre. Namur was then garrisoned by the Belgian 4th Division, to which was added, on the 22nd, part of the French 8th Brigade under General Mangin. Lanrezac had not even been able to get all his strength aligned on the Sambre when the shock came.23 On the 21st, his five corps were grouped as follows: The 1st Corps (Franchet d’Espérey) was facing east toward the Meuse north of Dinant, pending the arrival, on the evening of the 22nd, of the Bouttegourd Reserve Division; the 10th Corps (Defforges), with the 37th (African) Division, on the heights of Fosse and Arsimont, faced the Sambre crossings at Tamines and Auvelais; the 3rd Corps (Sauret) stood before Charleroi, with the 38th (African) Division in reserve; the 18th Corps (de Mas-Latrie) was behind the left, south of Thuin. Of General Valabrègue’s group of reserve divisions, one was yet to come into line on the right and one on the left.

Could Lanrezac have accomplished anything by pressing forward into the unknown with tired troops? The question might be debatable had the Allies had only Bülow to deal with; but, as we shall see, this was by no means the case. Meanwhile, the British made a day’s march beyond the Sambre. On the 22nd they continued the French line west-north-westward, still without an enemy before them, and entrenched themselves, the 5th Cavalry Brigade occupying the right, the 1st Corps (Haig) from Binche to Mons, and the 2nd Corps (Smith-Dorrien) along the canal to Condé-on-Scheldt. West and south-west of this point, there was nothing but the aforesaid groups of French Territorials. The I German Army not yet having revealed itself, the general idea of the French command, to attack across the Sambre with its centre, and then, if successful, to swing round the Allied left in a north-easterly direction against what was supposed to be the German right flank, still seemed feasible. But, in fact, Kluck’s Army lay beyond Bülow’s to the north-west, on the line Brussels–Valenciennes; it is quite possible, therefore, that a preliminary success by Lanrezac would have aggravated the later defeat.

Battle of Charleroi–Mons

However that may be, the programme was at once stultified by the unexpected speed and force of the German approach. The bombardment of the nine forts of Namur had begun on August 20. Bülow’s Army reached the Sambre on the following day, and held the passages at night. Lanrezac’s orders had become plainly impossible, and he did not attempt to fulfil them. Early on the afternoon of the 21st, while Kluck approached on one hand and Hausen on the other, Bülow’s X Corps and Guard Corps attacked the 3rd and 10th Corps forming the apex of the French triangle. These, not having entrenched themselves, and having, against Lanrezac’s express orders, advanced to the crossings between Charleroi and Namur, there fell upon strong defences flanked by machine-guns, and were driven back and separated. Despite repeated counter-attacks, the town of Chatelet was lost. On the 22nd, these two French corps, with a little help from the 18th, had again to bear the full weight of the enemy. Their artillery preparation was inadequate, and charges of a reckless bravery did not improve their situation.24 Most desperate fighting took place in and around Charleroi. The town was repeatedly lost and won back by the French during the day and the following morning; in course of these assaults, the Turcos inflicted heavy losses on the Prussian Guard. While the 10th Corps, cruelly punished at Tamines and Arsimont, fell back on Mettet, the 3rd found itself threatened with envelopment on the west by Bülow’s X Reserve and VII Corps, debouching from Chatelet and Charleroi.

That evening, the 22nd, Lanrezac thought there was still a chance of recovery. “The enemy does not yet show any numerical superiority,” he wrote, “and the 5th Army, though shaken, is intact.” The 1st Corps was at length free, having been relieved in the river angle south of Namur by the 51st Reserve Division; the 18th Corps had arrived and was in full action on the left about Thuin; farther west, other reserves were coming up, and the British Army had not been seriously engaged. The French commander therefore asked his British confrère to strike north-eastward at Bülow’s flank. The Field-Marshal found this request “quite impracticable” and scarcely comprehensible. He had conceived, rightly or wrongly, a very unfavourable idea of Lanrezac’s qualities; and the sight of infantry and artillery columns of the 5th Army in retreat southward that morning, before the two British corps had reached their positions on either side of Mons, had been a painful surprise. He was already in advance of the shaken line of the 5th Army; and news was arriving which indicated a grave threat of envelopment by the north-west. French had come out from England with clear warning that, owing to the impossibility of rapid or considerable reinforcement, he must husband his forces, and that he would “in no case come in any sense under the orders of any Allied General.” He now, therefore, replied to Lanrezac that all he could promise was to hold the Condé Canal position for twenty-four hours; thereafter, retreat might be necessary.

On the morning of the 23rd, Bouttegourd and D’Espérey opened an attack on the left flank of the Prussian Guard, while the British were receiving the first serious shock of the enemy. The French centre, however, was in a very bad way. During the afternoon the 3rd Corps gave ground, retreating in some disorder to Walcourt; the 18th was also driven back. About the same time, four surprises fell crushingly upon the French command. The first was the fall of Namur, which had been looked to as pivot of the French right. Although the VII Reserve Corps did not enter the town till 8 p.m., its resistance was virtually broken in the morning. Most of the forts had been crushed by the German 11- and 16-inch howitzers; it was with great difficulty that 12,000 men, a half of the garrison, escaped, ultimately to join the Belgian Army at Antwerp, Secondly, the Saxon Army, hitherto hidden in the Ardennes and practically unknown to the French Command, suddenly made an appearance on Lanrezac’s right flank. On the 23rd, the XII Corps captured Dinant, forced the passages of the Meuse there and at Hastière, drove in the Bouttegourd Division (51st Reserve), and reached Onhaye. The 1st Corps, thus threatened in its rear, had to break its well-designed attack on the Prussian Guard, and face about eastward. It successfully attacked the Saxons at Onhaye, and prevented them from getting more than one division across the river that night, so that the retreat of the French Army from the Sambre toward Beaumont and Philippeville, ordered by Lanrezac on his own responsibility at 9 p.m., was not impeded. Thirdly, news arrived of the failure of the French offensive in the Ardennes.

The fourth surprise lay in the discovery that the British Army had before it not one or two corps, as was supposed until the afternoon of August 23, but three or four active corps and two cavalry divisions of Kluck’s force, a part of which was already engaged in an attempt to envelop the extreme left of the Allies. Only at 5 p.m.—both the intelligence and the liaison services seem to have failed—did the British commander, who had been holding pretty well since noon against attacks that did not yet reveal the enemy’s full strength, learn from Joffre that this force was twice as large as had been reported in the morning, that his west flank was in danger, and that “the two French reserve divisions and the 5th French Army on my right were retiring.” About midnight the fall of Namur and the defeat of the French 3rd and 4th Armies were also known. In face of this “most unexpected” news, a 15-miles withdrawal to the line Maubeuge–Jenlain was planned; and it began at dawn on the 24th, fighting having continued through the previous night.

Some French writers have audaciously sought to throw a part, at least, of the responsibility for the French defeat on the Sambre upon the small British Expeditionary Force. An historian so authorised as M. Gabriel Hanotaux, in particular, has stated that it was in line, instead of the 20th, as had been arranged, only on the 23rd, when the battle on the Sambre was compromised and the turning movement north-eastward from Mons which had been projected could no longer save the situation; and that Sir John French, instead of destroying Kluck’s corps one by one as they arrived, “retreated after three hours’ contact with the enemy,” hours before Lanrezac ordered the general retreat of the 5th Army.25 It is the barest justice to the first British continental Army, its commander, officers, and men, professional soldiers of the highest quality few of whom now survive, to say that these statements, made, no doubt, in good faith, are inaccurate, and the deductions from them untenable. It was not, and could not have been, arranged between the Allied commands that French’s two corps should be in line west and east of Mons, ready for offensive action, on August 20, when Lanrezac’s fore-guards were only just reaching the Sambre. General Joffre knew from Sir John, at their meeting on August 16, that the British force could not be ready till the 21st; and it was then arranged that it should advance that day from the Sambre to the Mons Canal (13 miles farther north). This was done. Bülow had then already seized the initiative. If the British could have arrived sooner, and the projected north-easterly advance had been attempted, Bülow’s right flank might have been troubled; but the way would have been left clear for Kluck’s enveloping movement, with disastrous consequences for the whole left of the Allies. It is not true that the British retreat preceded the French, or that it occurred after “three hours’ contact with the enemy.” Lanrezac’s order for the general retreat was given only at 9 p.m.; but his corps had been falling back all afternoon. Kluck’s attack began at 11 a.m. on the 23rd, and became severe about 3 p.m. An hour later, Bülow’s right struck in between Lanrezac’s 3rd and 18th Corps, compelling them to a retreat that left a dangerous gap between the British and French Armies. From this time the British were isolated and continuously engaged. “When the news of the retirement of the French and the heavy German threatening on my front reached me,” says the British commander (in his dispatch of September 7, 1914), “I endeavoured to confirm it by aeroplane reconnaissance; and, as a result of this, I determined to effect a retirement to the Maubeuge position at daybreak on the 24th. A certain amount of fighting continued along the whole line throughout the night; and, at daybreak on the 24th, the 2nd Division made a powerful demonstration as if to retake Binche,” to enable the 2nd Corps to withdraw. The disengagement was only procured with difficulty and considerable loss. Had it been further delayed, the two corps would have been surrounded and wiped out. They were saved by courage and skill, and by the mistakes of Kluck, who failed to get some of his forces up in time, and spent others in an enveloping movement when a direct attack was called for.