полная версия

полная версияA History of North American Birds, Land Birds. Volume 1

The T. swainsoni is found in abundance westward to the western limit of the Rocky Mountain system; in the latter region specimens at all seasons have the olive of a clearer, more greenish shade than in any Eastern examples; this clearer tint is analogous with that of the Rocky Mountain form of pallasi (auduboni). In precisely the same region inhabited by the pallasi var. nanus the swainsoni also has a representative form,—the var. ustulatus. This resembles in pattern the var. swainsoni, but the olive above is decidedly more rufescent,—much as in Rocky Mountain specimens of T. fuscescens; the spots on jugulum and breast are also narrower, as well as hardly darker in color than the back; and the tail is longer than in Rocky Mountain swainsoni, in which latter it is longer than in Eastern examples. The remaining species—mustelinus, fuscescens, and aliciæ—extend no farther west than the Rocky Mountains; the first and last only toward their eastern base, while the second breeds abundantly as far as the eastern limit of the Great Basin.

The T. fuscescens, from the Rocky Mountains, is considerably darker in color above, while the specks on the throat and jugular are sparser or more obsolete than in Eastern birds.

In T. mustelinus, the only two Western specimens in the collection (Mount Carroll, Ills., and Fort Pierre) have the rump of a clearer grayish than specimens from the Atlantic Coast; in all other respects, however, they appear to be identical. Some Mexican specimens, being in winter plumage, have the breast more buffy than Northern (spring or summer) examples, and the rufous of the head, etc. is somewhat brighter.

In aliciæ, no difference is observed between Eastern and Western birds; the reason is, probably, that the breeding-ground of all is in one province, though their migrations may extend over two. There is, however, a marked difference between the spring and autumn plumage; the clear grayish of the former being replaced, in the latter, by a snuffy brown, or sepia tint,—this especially noticeable on wings and tail.

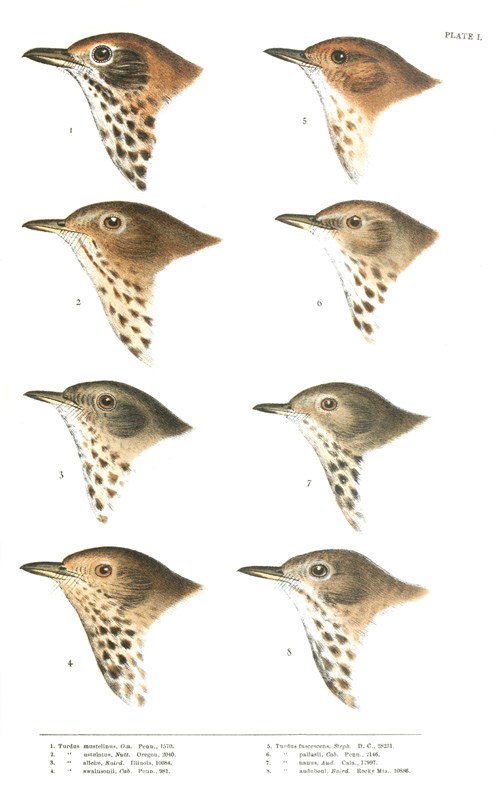

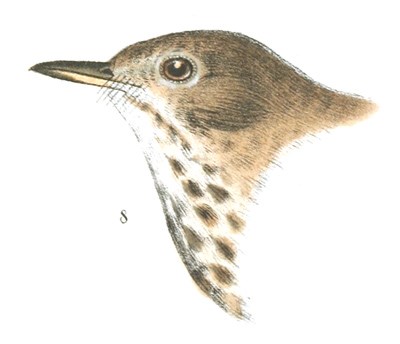

PLATE I.

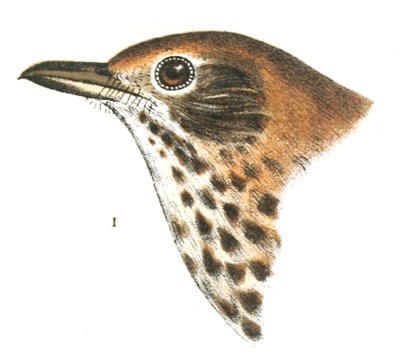

1. Turdus mustelinus, Gm. Pa., 1570.

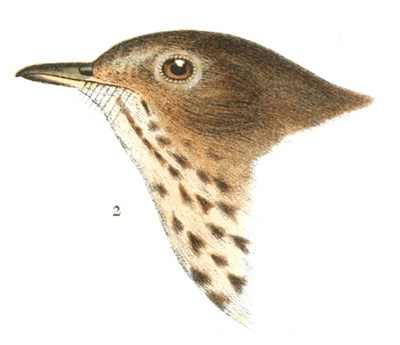

2. Turdus ustulatus, Nutt. Oregon, 2040.

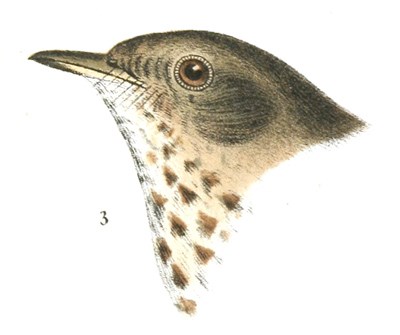

3. Turdus aliciæ, Baird. Illinois, 10084.

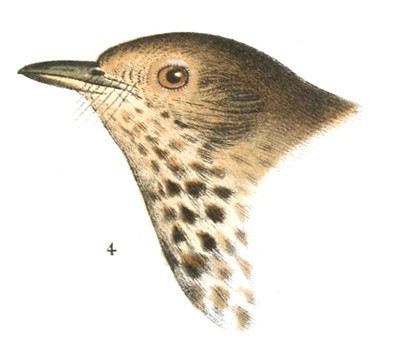

4. Turdus swainsoni, Cab. Penn., 981.

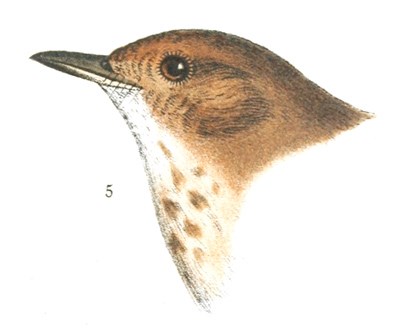

5. Turdus fuscescens, Steph., D. C., 28231.

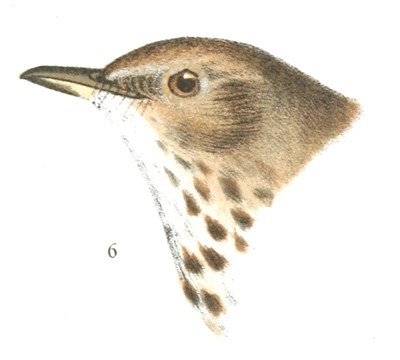

6. Turdus pallasii, Cab. Penn., 2146.

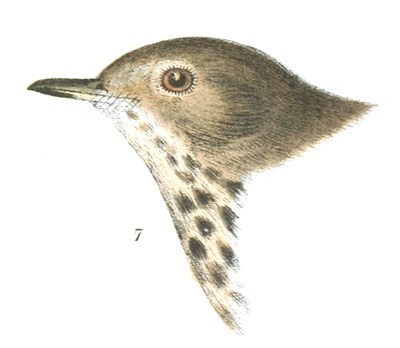

7. Turdus nanus, Aud. Cala., 17997.

8. Turdus auduboni, Baird. Rocky Mts., 10886.

The following synopsis is intended to show the characters of the different species and varieties.

1. Spots beneath rounded, covering breast and sidesA. Rufous brown above, becoming much brighter toward the bill, and more olivaceous on the tail. Beneath white; whole breast with rounded spots. Nest on tree; eggs pale blue.

1. T. mustelinus. Beneath nearly pure white, with rounded blackish spots over the whole breast, sides, and upper part of abdomen; wing, 4.25; tail, 3.05; culmen, .80; tarsus, 1.26. Hab. Eastern Province United States, south to Guatemala and Honduras. Cuba and Bermuda of West Indies.

2. Spots beneath triangular, on breast onlyB. Entirely uniform in color above,—olivaceous, varying to reddish or greenish with the species. Beneath whitish, with a wash of brownish across the breast and along sides. Spots triangular, and confined to the breast. Nest on trees or bushes; eggs blue spotted with brownish; except in T. fuscescens, which nests on the ground, and lays plain blue eggs.

a. No conspicuous light orbital ring.

2. T. fuscescens. Yellowish-rufous or olive-fulvous above; a strong wash of pale fulvous across the throat and jugulum, where are very indistinct cuneate spots of same shade as the back. Wing, 4.10; tail, 3.00; culmen, .70; tarsus, 1.15. Hab. Eastern Province of North America. North to Nova Scotia and Fort Garry. West to Great Salt Lake. South (in winter) to Panama and Brazil. Cuba.

3. T. aliciæ. Grayish clove-brown above; breast almost white, with broad, blackish spots; whole side of head uniform grayish. Wing, 4.20; tail, 3.20; culmen, .77; tarsus, 1.15. Hab. Eastern Province North America from shore of Arctic Ocean, Fort Yukon, and Kodiak to Costa Rica. West to Missouri River. Cuba.

b. A conspicuous orbital ring of buff.

4. T. swainsoni.

Greenish-olive above, breast and sides of head strongly tinged with buff. Spots on breast broad, distinct, nearly black. Length, 7.00; wing, 3.90; tail, 2.90; culmen, .65; tarsus, 1.10. Hab. Eastern and Middle Provinces of North America. North to Slave Lake, south to Ecuador, west to East Humboldt Mountains … var. swainsoni.

Brownish-olive above, somewhat more rufescent on wing; breast and head strongly washed with dilute rufous. Spots on breast narrow, scarcely darker than back. Wing, 3.85; tail, 3.00; culmen, .70; tarsus, 1.10. Hab. Pacific Province of United States. Guatemala … var. ustulatus.

C. Above olivaceous, becoming abruptly more reddish on upper tail-coverts and tail. Spots as in swainsoni, but larger and less transverse,—more sharply defined. An orbital ring of pale buff. Nest on ground; eggs blue, probably unspotted.

5. T. pallasi.

Olivaceous of upper parts like ustulatus. Reddish of upper tail-coverts invading lower part of rump; no marked difference in tint between the tail and its upper coverts. Flanks and tibiæ yellowish olive-brown; a faint tinge of buff across the breast. Eggs plain. Wing, 3.80; tail, 3.00; culmen, .70; tarsus, 1.20. Hab. Eastern Province of United States (only?) … var. pallasi.

Olivaceous of upper parts like swainsoni. Reddish of tail not invading the rump, and the tail decidedly more castaneous than the upper coverts. Beneath almost pure white; scarcely any buff tinge on breast; flanks and tibiæ grayish or plumbeous olive. Size smaller than swainsoni; bill depressed. Wing, 3.50; tail, 2.60; culmen, .60; tarsus, 1.15. Hab. Western Province of North America, from Kodiak to Cape St. Lucas. East to East Humboldt Mountains … var. nanus.

Olivaceous above, like preceding; the upper tail-coverts scarcely different from the back. Tail yellowish-rufous. Beneath like nanus. Size larger than swainsoni. Wing, 4.20; tail, 3.35; culmen, .80; tarsus, 1.30. Hab. Rocky Mountains. From Fort Bridger, south (in winter) to Southern Mexico … var. auduboni.

Turdus mustelinus, GmelinTHE WOOD THRUSHTurdus mustelinus, Gmelin, Syst. Nat. I, 1788, 817.—Audubon, Orn. Biog. I, 1832, 372, pl. 73.—Ib. Birds Am. III, 1841, 24, pl. 144.—D’Orb. La Sagra’s Cuba Ois. 1840, 49.—Baird, Birds N. Am. 1858, 212.—Ib. Rev. Am. Birds, 1864, 13.—Sclater, P. Z. S. 1856, 294, and 1859, 325.—Jones, Nat. in Bermuda, 26.—Gundlach, Repertorio, 1865, 228.—Maynard.—Samuels, 146. Turdus melodus, Wils. Am. Orn. I, 1808, 35, pl. ii. Turdus densus, Bonap. Comptes Rendus, XXVIII, 1853, 2.—Ib. Notes Delattre, 1854, 26 (Tabasco).

Additional figures: Vieillot, Ois. Am. Sept. II, pl. lxii.—Wilson, Am. Orn. I, pl. ii.

Sp. Char. Above clear cinnamon-brown, on the top of the head becoming more rufous, on the rump and tail olivaceous. The under parts are clear white, sometimes tinged with buff on the breast or anteriorly, and thickly marked beneath, except on the chin and throat and about the vent and tail-coverts, with sub-triangular, sharply defined spots of blackish. The sides of the head are dark brown, streaked with white, and there is also a maxillary series of streaks on each side of the throat, the central portion of which sometimes has indications of small spots. Length, 8.10 inches; wing, 4.25; tail, 3.05; tarsus, 1.26. Young bird similar to adult, but with rusty yellow triangular spots in the ends of the wing coverts.

Hab. U. S. east of Missouri plains, south to Guatemala. Bermuda (not rare). Cuba, La Sagra; Gundlach. Honduras, Moore. Cordova, Scl. Orizaba (winter), Sumichr.

Habits. The Wood Thrush, without being anywhere a very abundant species, is common throughout nearly every portion of the United States between the Mississippi River and the Atlantic. It breeds in every portion of the same extended area, at least as far as Georgia on the south and Massachusetts on the north. Beyond the last-named State, it rarely, if ever, breeds on the coast. In the interior it has a higher range, nesting around Hamilton, C. W. So far as I am aware it is unknown, or very rare, in the States of Vermont, New Hampshire, and Maine.

It makes its appearance early in April in the Middle States, but in New England not until four or five weeks later, appearing about the 10th of May. Their migrations in fall are more irregular, being apparently determined by the abundance of their food. At times they depart as early as the first of September, but sometimes not until the last of October. It winters in Central America, where it is quite abundant at that season.

The favorite localities of the Wood Thrush are the borders of dense thickets, or low damp hollows shaded by large trees. Yet its habits are by no means so retiring, or its nature so timid, as these places of resort would lead us to infer. A small grove in Roxbury, now a part of Boston, in close proximity to a dwelling-house, was for many years the favorite resort of these birds, where several pairs nested and reared their young, rarely even leaving their nests, which were mostly in low bushes, wholly unmindful of the curious children who were their frequent visitors. The same fearless familiarity was observed at Mount Auburn, then first used as a public cemetery. But in the latter instance the nest was always placed high up on a branch of some spreading tree, often in conspicuous places, but out of reach. Mr. J. A. Allen refers to several similar instances where the Wood Thrush did not show itself to be such a recluse as many describe it. In one case a pair built their nest within the limits of a thickly peopled village, where there were but few trees, and a scanty undergrowth. In another a Wood Thrush lived for several successive summers among the elms and maples of Court Square in the city of Springfield, Mass., undisturbed by the passers by or the walkers beneath, or the noise and rattle of the vehicles on the contiguous streets.

The song of this thrush is one of its most remarkable and pleasing characteristics. No lover of sweet sounds can have failed to notice it, and, having once known its source, no one can fail to recognize it when heard again. The melody is one of great sweetness and power, and consists of several parts, the last note of which resembles the tinkling of a small bell, and seems to leave the conclusion suspended. Each part of its song seems sweeter and richer than the preceding.

The nest is usually built on the horizontal branch of a small forest-tree, six or eight feet from the ground, and, less frequently, in the fork of a bush. The diameter is about 5 inches, and the depth 3¾, with a cavity averaging 3 inches across by 2¼ in depth. They are firm, compact structures, chiefly composed of decayed deciduous leaves, closely impacted together, and apparently thus combined when in a moistened condition, and afterward dried into a firmness and strength like that of parchment. These are intermingled with, and strengthened by, a few dry twigs, and the whole is lined with fine roots and a few fine dry grasses. Occasionally, instead of the solid frame of impacted leaves, we find one of solidified mud.

The eggs of the Wood Thrush, usually four in number, sometimes five, are of a uniform deep-blue tint, with but a slight admixture of yellow, which imparts a greenish tinge. Their average measurements are 1.00 by .75 inch.

Turdus fuscescens, StephensTAWNY THRUSH; WILSON’S THRUSHTurdus mustelinus, Wilson, Amer. Ornithology, V, 1812, 98, pl. 43 (not of Gmelin).

Turdus fuscescens, Stephens, Shaw’s Gen. Zoöl. Birds, X, I, 1817, 182. Cab. Jour. 1855, 470 (Cuba).—Baird, Birds N. Am. 1858, 214.—Ib. Rev. Am. B. 1864, 17.—Gundi. Repertorio, 1865, 228 (Cuba, not rare). Pelzeln, Orn. Bras. II, 1868, 92. (San Vicente, Brazil, December.)—Samuels, 150.—Sclater, P. Z. S. 1859, 326.—Ib. Catal. Am. Birds, 1861, 2, No. 10. Turdus silens, Vieill. Encyclop. Méth. II, 1823, 647 (based on T. mustelinus, Wils.). Turdus wilsonii, Bon. Obs. Wils. 1825, No. 73. Turdus minor, D’Orb. La Sagra’s Cuba, Ois. 1840, 47, pl. v (Cuba).

Sp. Char. Above, and on sides of head and neck, nearly uniform light reddish-brown, with a faint tendency to orange on the crown and tail. Beneath, white; the fore part of the breast and throat (paler on the chin) tinged with pale brownish-yellow, in decided contrast to the white of the belly. The sides of the throat and the fore part of the breast, as colored, are marked with small triangular spots of light brownish, nearly like the back, but not well defined. There are a few obsolete blotches on the sides of the breast (in the white) of pale olivaceous; the sides of the body tinged with the same. Tibiæ white. The lower mandible is brownish only at the tip. The lores are ash-colored, the orbital region grayish. Length, 7.50; wing, 4.25; tail, 3.20; tarsus; 1.20.

Hab. Eastern North America, Halifax to Fort Bridger, and north to Fort Garry. Cuba, Panama, and Brazil (winter). Orizaba (winter), Sumichrast.

Habits. This species is one of the common birds of New England, and is probably abundant in certain localities throughout all the country east of the Rocky Mountains, as far to the north as the 50th parallel, and possibly as far as the wooded country extends. Mr. Maynard did not meet with it in Northern New Hampshire. Mr. Wm. G. Winton obtained its nest and eggs at Halifax, N. S.; Mr. Boardman found them also on the Gulf of St. Lawrence, and at St. Stephen’s, N. B.; Mr. Couper at Quebec; Mr. Krieghoff at Three Rivers, Canada; Donald Gunn at Selkirk and Red River; and Mr. Kumlien and Dr. Hoy in Wisconsin. Mr. McIlwraith also gives it as common at Hamilton, West Canada. It breeds as far south as Pennsylvania, and as far to the west as Utah, and occurs, in the breeding season, throughout Maine, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Canada.

Mr. Ridgway found this thrush very abundant among the thickets in the valleys of the Provo, Weber, and Bear rivers, in Utah, and very characteristic of those portions of the country.

It arrives in Massachusetts early in May, usually with the first blossoms of the pear, ranging from the 5th to the 20th. It is strictly of woodland habits, found almost entirely among clumps of trees, and obtaining its food from among their branches, or on the ground among the fallen leaves. It moves south from the 10th to the 25th of September, rarely remaining till the first week in October.

It is timid, distrustful, and retiring; delighting in shady ravines, the edges of thick close woods, and occasionally the more retired parts of gardens; where, if unmolested, it will frequent the same locality year after year.

The song of this thrush is quaint, but not unmusical; variable in its character, changing from a prolonged and monotonous whistle to quick and almost shrill notes at the close. Their melody is not unfrequently prolonged until quite late in the evening, and, in consequence, in some portions of Massachusetts these birds are distinguished with the name of Nightingale,—a distinction due rather to the season than to the high quality of their song. Yet Mr. Ridgway regards it, as heard by himself in Utah, as superior in some respects to that of all others of the genus, though far surpassed in mellow richness of voice and depth of metallic tone by that of the Wood Thrush (T. mustelinus). To his ear there was a solemn harmony and a beautiful expression which combined to make the song of this surpass that of all the other American Wood Thrushes. The beauty of their notes appeared in his ears “really inspiring; their song consisting of an inexpressibly delicate metallic utterance of the syllables ta-weel´ ah, ta-weel´ ah, twil´ ah, twil´ ah, accompanied by a fine trill which renders it truly seductive.” The last two notes are said to be uttered in a soft and subdued undertone, producing thereby, in effect, an echo of the others.

The nest is always placed near the ground, generally raised from it by a thick bed of dry leaves or sticks; sometimes among bushes, but never in the fork of a bush or tree, or if so, in very rare and exceptional cases. When incubation has commenced, the female is reluctant to leave her nest. If driven off she utters no complaint, but remains close at hand and returns at the first opportunity.

They construct their nest early in May, and the young are hatched in the latter part of that month, or the first of June. They raise two broods in the season. The nest, even more loosely put together than that of the Ground Swamp Robin (T. pallasi), is often with difficulty kept complete. It is about 3 inches in height, 4½ in diameter, with a cavity 1½ inches deep and 3 in width, and composed of dry bark, dead leaves, stems, and woody fibres, intermingled with grasses, caricas, sedges, etc., and lined with soft skeleton leaves. A nest from Wisconsin was composed entirely of a coarse species of Sparganeum; the dead stalks and leaves of which were interwoven with a very striking effect.

The eggs, usually four, sometimes five in number, are of a uniform green color, with a slight tinge of blue, and average .94 by .66 of an inch in diameter.

Turdus aliciæ, BairdGRAY-CHEEKED THRUSH; ALICE’S THRUSHTurdus aliciæ, Baird, Birds N. Am. 1858, 217, plate 81, f. 2.—Ib. Review Am. Birds, I, 1864, 21.—Coues, Pr. Ac. N. Sc. Aug. 1861, 217 (Labrador).—Ib. Catal. Birds of Washington.—Gundlach, Repertorio, 1865, 229 (Cuba).—Lawr. Ann. N. Y. Lyc. IX, 91 (Costa Rica).—Dall and Bannister, Birds Alaska.—Ridgway, Report.

Sp. Char. Above nearly pure dark olive-green; sides of the head ash-gray; the chin, throat, and under parts white; purest behind. Sides of throat and across the breast with arrow-shaped spots of dark plumbeous-brown. Sides of body and axillaries dull grayish-olivaceous. Tibiæ plumbeous; legs brown. Length, nearly 8 inches; wing, 4.20; tail, 3.20; tarsus, 1.15.

Hab. Eastern North America to shores of Arctic Ocean, and along northern coast from Labrador to Kodiak, breeding in immense numbers between the mouths of Mackenzie and Coppermine. West to Fort Yukon and Missouri River States. Winters south to Costa Rica. Chiriqui, Salvin; Cuba, Gundlach.

As originally described, this species differs from swainsoni in larger size, longer bill, feet, and wings especially, straighter and narrower bill. The back is of a greener olive. The breast and sides of the head are entirely destitute of the buff tinge, or at best this is very faintly indicated on the upper part of the breast. The most characteristic features are seen on the side of the head. Here there is no indication whatever of the light line from nostril to eye, and scarcely any of a light ring round the eye,—the whole region being grayish-olive, relieved slightly by whitish shaft-streaks on the ear-coverts. The sides of body, axillars, and tibiæ are olivaceous-gray, without any of the fulvous tinge seen in swainsoni. The bill measures .40 from tip to nostril, sometimes more; tarsi, 1.21; wing, 4.20; tail, 3.10,—total, about 7.50. Some specimens slightly exceed these dimensions; few, if any, fall short of them.

In autumn the upper surface is somewhat different from that in spring, being less grayish, and with a tinge of rich sepia or snuff-brown, this becoming gradually more appreciable on the tail.

A specimen from Costa Rica is undistinguishable from typical examples from the Eastern United States.

Habits. This species, first described in the ninth volume of the Pacific Railroad Surveys, bears so strong a resemblance to the Olive-backed Thrush (T. swainsoni), that its value as a species has often been disputed. It was first met with in Illinois. Since then numerous specimens have been obtained from the District of Columbia, from Labrador, and the lower Mackenzie River. In the latter regions it was found breeding abundantly. It was also found in large numbers on the Anderson River, but was rare on the Yukon, as well as at Great Slave Lake, occurring there only as a bird of passage to or from more northern breeding-grounds.

In regard to its general habits but little is known. Dr. Coues, who found it in Labrador, breeding abundantly, speaks of meeting with a family of these birds in a deep and thickly wooded ravine. The young were just about to fly. The parents evinced the greatest anxiety for the safety of their brood, endeavoring to lead him from their vicinity by fluttering from bush to bush, constantly uttering a melancholy pheugh, in low whistling tone. He mentions that all he saw uttered precisely the same note, and were very timid, darting into the most impenetrable thickets.

This thrush is a regular visitant to Massachusetts, both in its spring and in its fall migration. It arrives from about the first to the middle of May, and apparently remains about a week. It passes south about the first of October. Occasionally it appears and is present in Massachusetts at the same time with the Turdus swainsoni. From this species I hold it to be unquestionably distinct, and in this opinion I am confirmed by the observations of two very careful and reliable ornithologists, Mr. William Brewster of Cambridge, one of our most promising young naturalists, and Mr. George O. Welch of Lynn, whose experience and observations in the field are unsurpassed. They inform me that there are observable between these two forms certain well-marked and constant differences, that never fail to indicate their distinctness with even greater precision than the constant though less marked differences in their plumage.

The Turdus aliciæ comes a few days the earlier, and is often in full song when the T. swainsoni is silent. The song of the former is not only totally different from that of the latter, but also from that of all our other Wood Thrushes. It most resembles the song of T. pallasi, but differs in being its exact inverse, for whereas the latter begins with its lowest notes and proceeds on an ascending scale, the former begins with its highest, and concludes with its lowest note. The song of the T. swainsoni, on the other hand, exhibits much less variation in the scale, all the notes being of nearly the same altitude.

I am also informed that while the T. swainsoni is far from being a timid species, but may be easily approached, and while it seems almost invariably to prefer the edges of the pine woods, and is rarely observed in open grounds or among the bare deciduous trees, the habits of the T. aliciæ are the exact reverse in these respects. It is not to be found in similar situations, but almost always frequents copses of hard wood, searching for its food among their fallen leaves. It is extremely timid and difficult to approach. As it stands or as it moves upon the ground, it has a peculiar erectness of bearing which at once indicates its true specific character so unmistakably that any one once familiar with its appearance can never mistake it for T. swainsoni nor for any other bird.