полная версия

полная версияA History of North American Birds, Land Birds. Volume 2

Dr. Cooper found this Magpie abundant in the valleys of California, especially near the middle of the State, except during the spring months, when none were seen in the Santa Clara Valley, the supposition being that they had retired eastward to the mountains to build their nests. At Santa Barbara he found them numerous in April and May, and saw their nests in oak-trees. The young were already fledged by the 25th of April. The nest, he states, is composed of a large mass of coarse twigs twisted together in a spherical form, with a hole in the side. The eggs he saw resembled those of the other species, and are described as being whitish-green, spotted with cinereous-gray and olive-brown. They also breed abundantly about Monterey. They have not been traced to the northern border of the State.

Their food, Dr. Cooper adds, consists of almost everything animal and vegetable that they can find, and they come about farms and gardens to pick up whatever they can meet with. They have a loud call that sounds like pait-pait, with a variety of chattering notes, in tone resembling the human voice, which, indeed, they can be taught to imitate.

An egg of this species from Monterey, California, is of a rounded oval shape, a little less obtuse at one end than the other. The ground-color is a light drab, so closely marked with fine cloudings of an obscure lavender color as nearly to conceal the ground, and to give the egg the appearance of an almost uniform violet-brown. It measures 1.20 inches in length by .90 in breadth.

Genus CYANURA, SwainsonCyanurus, Swainson, F. Bor.-Am. II, 1831, 495, Appendix. (Type, Corvus cristatus, Linn.)

Cyanocitta, Cabanis, Mus. Hein. 1851 (not of Strickland, 1845).

Cyanura cristata.

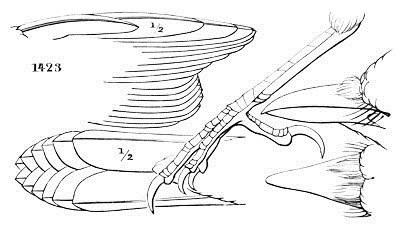

1423

Gen. Char. Head crested. Wings and tail blue, with transverse black bars; head and back of the same color. Bill rather slender, somewhat broader than high at the base; culmen about equal to the head. Nostrils large, nearly circular, concealed by bristles. Tail about as long as the wings, lengthened, graduated. Hind claw large, longer than its digit.

Species and VarietiesCommon Characters. Wings and tail deep blue, the latter, with the secondaries and tertials, sometimes also the greater coverts, barred with black.

A. Greater coverts, tertials, secondaries, and tail-feathers tipped broadly with white; lower parts generally, including lateral and under parts of head, whitish.

C. cristata. Head above, back, scapulars, lesser wing-coverts, rump and upper tail-coverts, light ashy purplish-blue; a narrow frontal band, a loral spot, streak behind the eye, and collar round the neck, commencing under the crest, passing down across the end of the auriculars and expanding into a crescent across the jugulum, black; throat tinged with purplish-gray, the breast and sides with smoky-gray; abdomen, anal region, and crissum pure white. Wing, 5.70; tail, 6.00; bill, 1.25; tarsus, 1.35; middle toe, .85; crest, 2.20. Hab. Eastern Province of North America.

B. No white on wing or tail; lower parts deep blue.

C. stelleri. Color deep blue, less intense than on wings and tail, except dorsal region, which may be deep blue, ashy-brown, or sooty-black. Head and neck dark grayish-brown, dusky-blue, or deep black, the throat more grayish.

a. No white patch over the eye; throat and chin not abruptly lighter than adjacent parts; secondary coverts not barred with black.

Whole head, neck, jugulum, and dorsal region plain sooty-black; no blue streaks on forehead, or else these only faintly indicated. The blue everywhere of a uniform dull greenish-indigo shade. Depth of bill, .45; crest, 2.60; wing, 6.00; tail, 6.00; culmen, 1.35; tarsus, 1.75; middle toe, 1.00. Hab. Northwest coast, from Sitka to the Columbia … var. stelleri.

Whole head, neck, jugulum, and dorsal region plumbeous-umber; the forehead conspicuously streaked with blue, and the crest washed with the same. The blue of two very different shades, the wings and tail being deep indigo, the body and tail-coverts greenish cobalt-blue. Depth of bill, .35; crest, 2.80; wing, 6.00; tail, 6.00; culmen, 1.25; tarsus, 1.55; middle toe, .90. Hab. Sierra Nevada, from Fort Crook to Fort Tejon … var. frontalis.

b. A patch of silky white over the eye; throat and chin abruptly lighter than the adjoining parts; secondary coverts barred distinctly with black.

Whole crest, cheeks, and foreneck deep black; the crest scarcely tinged with blue; dorsal region light ashy-plumbeous; forehead conspicuously streaked with milk-white. The blue contrasted as in var. frontalis. Depth of bill, .35; crest, 3.00; wing, 6.10; tail, 6.10; culmen, 1.25; tarsus, 1.65; middle toe, .90. Hab. Rocky Mountains of United States … var. macrolopha

Whole crest, cheeks, and foreneck deep black, the crest strongly tinged with blue; dorsal region greenish plumbeous-blue. The blue nearly uniform; forehead conspicuously streaked with bluish-white. Depth of bill, .35; crest, 2.80; wing, 5.90; tail, 5.90; culmen, 1.30; tarsus, 1.60; middle toe, .90. Hab. Highlands of Mexico … var. diademata.56

Whole crest, cheeks, and foreneck deep blue, lores black; dorsal region deep purplish-blue; forehead conspicuously streaked with light blue. The blue of a uniform shade—deep purplish-indigo—throughout. Depth of bill, .40; length of crest, 2.50; wing, 5.80; tail, 5.80; culmen, 1.30; tarsus, 1.60; middle toe, .95. Hab. Southeastern Mexico (Xalapa, Belize, etc.) … var. coronata.57

The different varieties just indicated under Cyanura stelleri, namely, stelleri, frontalis, macrolopha, diademata, and coronata, all appear to represent well-marked and easily defined races of one primitive species, the gradation from one form to the other being very regular, and agreeing with the general variation attendant upon geographical distribution. Thus, beginning with C. stelleri, we have the anterior part of head and body, including interscapular region, black, without any markings on the head. In frontalis the back is lighter, and a glossy blue shows on the forehead. In macrolopha the blue of posterior parts invades the anterior, tingeing them very decidedly, leaving the head black, with a blue shade to the crest; the forehead is glossed with bluish-white; the upper eyelids have a white spot. In coronata the blue tinge is deeper, and pervades the entire body, except the side of the head. The shade of blue is different from macrolopha, and more like that of stelleri; diademata, intermediate in habitat between macrolopha and coronata, is also intermediate in colors. The tail becomes rather more even, and the bill more slender, as we proceed from stelleri to coronata. The bars on the secondary coverts become darker in the same progression.

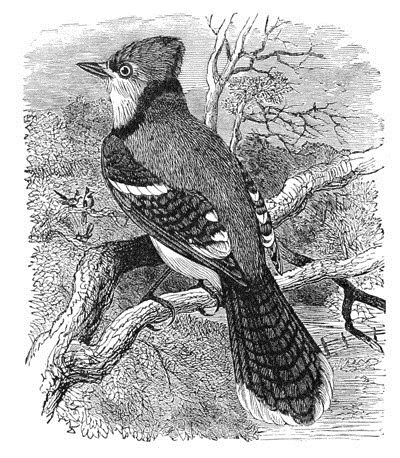

Cyanura cristata, SwainsonBLUE JAYCorvus cristatus, Linn. Syst. Nat. I, (10th ed.,) 1758, 106; (12th ed.,) 1766, 157.—Gmelin, Syst. Nat. I, 1788, 369.—Wilson, Am. Orn. I, 1808, 2, pl. I, f. 1.—Bon. Obs. Wilson, 1824, No. 41.—Doughty, Cab. N. H. II, 1832, 62, pl. vi.—Aud. Orn. Biog. II, 1834, 11; V, 1839, 475, pl. cii. Garrulus cristatus, “Vieillot, Encyclop. 890.”—Ib. Dict. XI, 477.—Bon. Syn. 1828, 58.—Sw. F. Bor.-Am. II, 1831, 293.—Vieillot, Galerie, I, 1824, 160, pl. cii.—Aud. Birds Am. IV, 110, pl. ccxxxi.—Max. Caban. J. 1858, VI, 192. Pica cristata, Wagler, Syst. Av. 1827, Pica, No. 8. Cyanurus cristatus, Swainson, F. Bor.-Am. II, 1831, App. 495.—Baird, Birds N. Am. 1858, 580.—Samuels, 364.—Allen, B. E. Fla. 297. Cyanocorax cristatus, Bon. List, 1838. Cyanocitta cristata, Strickland, Ann. Mag. N. H. 1845, 261.—Cabanis, Mus. Hein. 1851, 221. Cyanogarrulus cristatus, Bon. Consp. 1850, 376.

Sp. Char. Crest about one third longer than the bill. Tail much graduated. General color above light purplish-blue; wings and tail-feathers ultramarine-blue; the secondaries and tertials, the greater wing-coverts, and the exposed surface of the tail, sharply banded with black and broadly tipped with white, except on the central tail-feathers. Beneath white; tinged with purplish-blue on the throat, and with bluish-brown on the sides. A black crescent on the forepart of the breast, the horns passing forward and connecting with a half-collar on the back of the neck. A narrow frontal line and loral region black; feathers on the base of the bill blue, like the crown. Female rather duller in color, and a little smaller. Length, 12.25; wing, 5.65; tail, 5.75.

Hab. Eastern North America, west to the Missouri. Northeastern Texas (Dresser, Ibis, 1865, 494). North to Red River and Moose Factory.

Specimens from north of the United States are larger than more southern ones. A series of specimens from Florida, brought by Mr. Boardman, are quite peculiar in some respects, and probably represent a local race resident there. In these Florida specimens the wing and tail are each an inch or more shorter than in Pennsylvania examples, while the bill is not any smaller. The crest is very short; the white spaces on secondaries and tail-feathers more restricted.

Cyanura cristata.

Habits. The common Blue Jay of North America is found throughout the continent, from the Atlantic coast to the Missouri Valley, and from Florida and Texas to the fur regions nearly or quite to the 56th parallel. It was found breeding near Lake Winnepeg by Donald Gunn. It was also observed in these regions by Sir John Richardson. It was met with by Captain Blakiston on the forks of the Saskatchewan, but not farther west.

The entire family to which this Jay belongs, and of which it is a very conspicuous member, is nearly cosmopolitan as to distribution, and is distinguished by the remarkable intelligence of all its members. Its habits are striking, peculiar, and full of interest, often evincing sagacity, forethought, and intelligence strongly akin to reason. These traits belong not exclusively to any one species or generic subdivision, but are common to the whole family.

When first met with in the wild and unexplored regions of our country, the Jay appears shy and suspicious of the intruder, man. Yet, curious to a remarkable degree, he follows the stranger, watches all his movements, hovers with great pertinacity about his steps, ever keeping at a respectful distance, even before he has been taught to beware of the deadly gun. Afterwards, as he becomes better acquainted with man, the Jay conforms his own conduct to the treatment he receives. Where he is hunted in wanton sport, because of brilliant plumage, or persecuted because of unjust prejudices and a bad reputation not deserved, he is shy and wary, shuns, as much as possible, human society, and, when the hunter intrudes into his retreat, seems to delight to follow and annoy him, and to give the alarm to all dwellers of the woods that their foe is approaching.

In parts of the country, as in Iowa, Illinois, Indiana, and other Western States, where the Jay is unmolested and exempt from persecution, we find him as familiar and confiding as any of the favored birds of the Eastern States. In the groves of Iowa Mr. Allen found our Blue Jay nearly as unsuspicious as a Black-capped Titmouse. In Illinois he speaks of them as very abundant and half domestic. And again, in Indiana, in one of the principal streets of Richmond, the same gentleman found the nest of these birds in a lilac-bush, under the window of a dwelling. In the summer of 1843 I saw a nest of the Jay, filled with young, in a tree standing near the house of Mr. Audubon, in the city of New York. The habits of no two species can well be more unlike than are those which persecution on the one hand and kind treatment on the other have developed in this bird.

The Blue Jay, wherever found, is more or less resident. This is especially the case in the more southern portions of its area of reproduction. In Texas, Dr. Lincecum informs us, this Jay remains both summer and winter. It is there said to build its nest of mud, a material rarely if ever used in more northern localities; and when placed not far from dwelling-houses, it is lined with cotton thread, rags of calico, and the like. They are, he writes, very intelligent and sensible birds, subsisting on insects, acorns, etc. He has occasionally known them to destroy bats. In Texas they seem to seek the protection of man, and to nest near dwellings as a means of safety against Hawks. They nest but once a year, and lay but four eggs. In a female dissected by him, he detected one hundred and twelve ova, and from these data he infers that the natural life of a Jay is about thirty years.

Mr. Allen mentions finding the Blue Jay in Kansas equally at home, and as vivacious and even more gayly colored than at the North. While it seemed to have forgotten none of the droll notes and fantastic ways always to be expected from it, there was added to its manners that familiarity which characterizes it in the more newly settled portions of the country, occasionally surprising one with some new expression of feeling or sentiment, or some unexpected eccentricity in its varied notes, perhaps developed by the more southern surroundings.

The Blue Jay is arboreal in its habits. It prefers the shelter and security of thick covers to more open ground. It is omnivorous, eating either animal or vegetable food, though with an apparent preference for the former, feeding upon insects, their eggs and larvæ, and worms, wherever procurable. It also lays up large stores of acorns and beech mast for food in winter, when insects cannot be procured in sufficient abundance. Even at this season it hunts for and devours in large quantities the eggs of the destructive tent caterpillar.

The Jay is charged with a propensity to destroy the eggs and young of the smaller birds, and has even been accused of killing full-grown birds. I am not able to verify these charges, but they seem to be too generally conceded to be disputed. These are the only serious grounds of complaint that can be brought against it, and are more than outweighed, tenfold, by the immense services it renders to man in the destruction of his enemies. Its depredations on the garden or the farm are too trivial to be mentioned.

The Blue Jay is conspicuous as a musician. He exhibits a variety in his notes, and occasionally a beauty and a harmony in his song, for which few give him due credit. Wilson compares his position among our singing birds to that of the trumpeter in the band. His notes he varies to an almost infinite extent, at one time screaming with all his might, at another warbling with all the softness of tone and moderation of the Bluebird, and again imparting to his voice a grating harshness that is indescribable.

The power of mimicry possessed by the Jay, though different from, is hardly surpassed by that of the Mocking-Bird. It especially delights to imitate the cries of the Sparrow Hawk, and at other times those of the Red-tailed and Red-shouldered Hawks are given with such similarity that the small birds fly to a covert, and the inmates of the poultry-yard are in the greatest alarm. Dr. Jared P. Kirtland, of Cleveland, on whose grounds a large colony of Jays took up their abode and became very familiar, has given me a very interesting account of their habits. The following is an extract: “They soon became so familiar as to feed about our yards and corn-cribs. At the dawn of every pleasant day throughout the year, the nesting-season excepted, a stranger in my house might well suppose that all the axles in the country were screeching aloud for lubrication, hearing the harsh and discordant utterances of these birds. During the day the poultry might be frequently seen running into their hiding-places, and the gobbler with his upturned eye searching the heavens for the enemy, all excited and alarmed by the mimic utterances of the adapt ventriloquists, the Jays, simulating the cries of the Red-shouldered and the Red-tailed Hawks. The domestic circle of the barn-yard evidently never gained any insight into the deception by experience; for, though the trick was repeated every few hours, the excitement would always be re-enacted.”

When reared from the nest, these birds become very tame, and are perfectly reconciled to confinement. They very soon grow into amusing pets, learning to imitate the human voice, and to simulate almost every sound that they hear. Wilson gives an account of one that had been brought up in a family of a gentleman in South Carolina that displayed great intelligence, and had all the loquacity of a parrot. This bird could utter several words with great distinctness, and, whenever called, would immediately answer to its name with great sociability.

The late Dr. Esteep, of Canton, Ohio, an experienced bird-fancier, assured Dr. Kirtland that he has invariably found the Blue Jay more ingenious, cunning, and teachable than any other species of bird he has ever attempted to instruct.

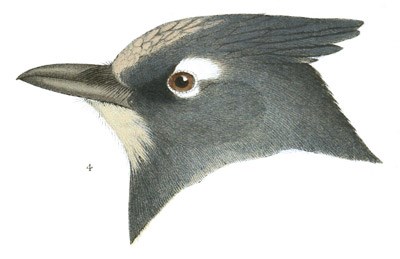

PLATE XXXIX.

1. Cyanura stelleri. ♂ Oregon, 46040.

2. Cyanura stelleri. var. frontalis. ♂ Sierra Nevada, 53639.

3. Cyanura macrolopha. ♂ Ariz., 41015.

4. Cyanura coronata. ♂ Xalapa, 16313.

Dr. Kirtland has also informed me of the almost invaluable services rendered to the farmers in his neighborhood, by the Blue Jays, in the destruction of caterpillars. When he first settled on his farm, he found every apple and wild-cherry tree in the vicinity extensively disfigured and denuded of its leaves by the larvæ of the Clisiocampa americana, or the tent caterpillar. The evil was so extensive that even the best farmers despaired of counteracting it. Not long after the Jays colonized upon his place he found they were feeding their young quite extensively with these larvæ, and so thoroughly that two or three years afterwards not a worm was to be seen in that neighborhood; and more recently he has searched for it in vain, in order to rear cabinet specimens of the moth.

The Jay builds a strong coarse nest in the branch of some forest or orchard tree, or even in a low bush. It is formed of twigs rudely but strongly interwoven, and is lined with dark fibrous roots. The eggs are usually five, and rarely six in number.

The eggs of this species are usually of a rounded-oval shape, obtuse, and of very equal size at either end. Their ground-color is a brownish-olive, varying in depth, and occasionally an olive-drab. They are sparingly spotted with darker olive-brown. In size they vary from 1.05 to 1.20 inches in length, and in breadth from .82 to .88 of an inch. Their average size is about 1.15 by .86 of an inch.

Cyanura stelleri, SwainsonSTELLER’S JAYCorvus stelleri, Gmelin, Syst. Nat. I, 1788, 370.—Lath. Ind. Orn. I, 1790, 158.—Pallas, Zoog. Rosso-As. I, 1811, 393.—Bonap. Zoöl. Jour. III, 1827, 49.—Ib. Suppl. Syn. 1828, 433.—Aud. Orn. Biog. IV, 1838, 453, pl. ccclxii. Garrulus stelleri, Vieillot, Dict. XII, 1817, 481.—Bonap. Am. Orn. II, 1828, 44, pl. xiii.—Nuttall, Man. I, 1832, 229.—Aud. Syn. 1839, 154.—Ib. Birds Am. IV, 1842, 107, pl. ccxxx (not of Swainson, F. Bor.-Am.?). Cyanurus stelleri, Swainson, F. Bor.-Am. II, 1831, 495, App. Pica stelleri, Wagler, Syst. Av. 1827, Pica, No. 10. Cyanocorax stelleri, Bon. List, 1838. Finsch, Abh. Nat. III, 1872, 40 (Alaska). Cyanocitta stelleri, Cab. Mus. Hein. 1851, 221. Newberry, P. R. R. Rep. VI, IV, 1857, 85. Cyanogarrulus stelleri, Bonap. Conspectus, 1850, 377. Steller’s Crow, Pennant, Arctic Zoöl. II, Sp. 139. Lath. Syn. I, 387. Cyanura s. Baird, Birds N. Am. 1858, 581 (in part). Lord, Pr. R. A. Inst. IV, 122 (British Columbia; nest).—Dall & Bannister, Trans. Chicago Acad. I, 1869, 486 (Alaska).—Cooper, Orn. Cal. 1, 1870, 298 (in part).

Sp. Char. Crest about one third longer than the bill. Fifth quill longest; second about equal to the secondary quills. Tail graduated; lateral feathers about .70 of an inch shortest. Head and neck all round, and forepart of breast, dark brownish-black. Back and lesser wing-coverts blackish-brown, the scapulars glossed with blue. Under parts, rump, tail-coverts, and wings greenish-blue; exposed surfaces of lesser quills dark indigo-blue; tertials and ends of tail-feathers rather obsoletely banded with black. Feathers of the forehead streaked with greenish-blue. Length, about 13.00; wing, 5.85; tail, 5.85; tarsus, 1.75 (1,921).

Hab. Pacific coast of North America, from the Columbia River to Sitka; east to St. Mary’s Mission, Rocky Mountains.

Habits. Dr. Suckley regarded Steller’s Jay as probably the most abundant bird of its size in all the wooded country between the Rocky Mountains and the Pacific. He describes it as tame, loquacious, and possessed of the most impudent curiosity. It is a hardy, tough bird, and a constant winter resident of Washington Territory. It is remarkable for its varied cries and notes, and seems to have one for every emotion or pursuit in which it is engaged. It also has a great fondness for imitating the notes of other birds. Dr. Suckley states that frequently when pleasantly excited by the hope of obtaining a rare bird, in consequence of hearing an unknown note issuing from some clump of bushes or thicket, he has been not a little disappointed by finding that it had issued from this Jay. It mimics accurately the principal cry of the Catbird.

Dr. Cooper also found it very common in all the forests on both sides of the Cascade Mountains. While it seemed to depend chiefly upon the forest for its food, in the winter it would make visits to the vicinity of houses, and steal anything eatable it could find within its reach, even potatoes. In these forages upon the gardens and farm-yards, they are both silent and watchful, evidently conscious of the peril of their undertaking, and when discovered they instantly fly off to the concealment of the forests. They also make visits to the Indian lodges when the owners are absent, and force their way into them if possible, one of their number keeping watch. In the forest they do not appear to be shy or timid, but boldly follow those who intrude upon their domain, screaming, and calling their companions around them. Hazel-nuts are one of their great articles of winter food; and Dr. Cooper states that, in order to break the shell, the Jay resorts to the ingenious expedient of taking them to a branch of a tree, fixing them in a crotch or cavity, and hammering them with its bill until it can reach the meat within. Their nest he describes as large, loosely built of sticks, and placed in a bush or low tree.

At certain seasons of the year its food consisted almost entirely of the seeds of the pine, particularly of P. brachyptera, which Dr. Newberry states he has often seen them extracting from the cones, and with which the stomachs of those he killed were usually filled. He found these birds ranging as far north as the line of the British Territory, and from the coast to the Rocky Mountains.

In his Western journey Mr. Nuttall met with these birds in the Blue Mountains of the Oregon, east of Walla-walla. There he found them scarce and shy. Afterwards he found them abundant in the pine forests of the Columbia, where their loud trumpeting clangor was heard at all hours of the day, calling out with a loud voice, djay-djay, or chattering with a variety of other notes, some of them similar to those of the common Blue Jay. They are more bold and familiar than our Jay. Watchful as a dog, no sooner does a stranger show himself in their vicinity than they neglect all other employment to come round him, following and sometimes scolding at him with great pertinacity and signs of irritability. At other times, stimulated by curiosity, they follow for a while in perfect silence, until something seems to arouse their ire, and then their vociferous cries are poured out with unceasing volubility till the intruder has passed from their view.