полная версия

полная версияA History of North American Birds, Land Birds. Volume 2

Dr. T. C. Henry also repeatedly noticed these birds in the vicinity of Fort Webster, in New Mexico. He first met with them near San Miguel, in July, 1852, where he observed a party of about thirty flitting through the cedars along the roadside. They were chiefly young birds, and were constantly alighting on the ground for the purpose of capturing lizards, which they killed with great readiness, and devoured. After that he repeatedly, in winter, saw these birds near Fort Webster, and usually in flocks of about forty or fifty. They evinced great wariness, and were very difficult of approach.

The flocks would usually alight near the summit of a hill and pass rapidly down its sides, all the birds keeping quite near to each other, and frequently alighting on the ground. They appeared to be very social, and kept up a continual twittering note. This bird, so far as Dr. Henry observed it, is exclusively a mountain species, and never seen on the plains or bottom-lands, and was never observed singly, or even in a single pair, but always in companies.

Dr. Newberry met with this species in the basin of the Des Chutes, in Oregon. He first noticed it in September. Early every morning flocks of from twenty-five to thirty of these birds came across, in their usual straggling flight, chattering as they flew to the trees on a hill near the camp, and then, from tree to tree, they made their way to the stream to drink. He describes their note, when flying or feeding, as a frequently repeated ca-ca-că. Sometimes, when made by a straggler separated from mate or flock, it was rather loud and harsh, but was usually soft and agreeable. When disturbed, their cry was harsher. They were very shy, and could only be shot by lying in wait for them. Subsequently he had an opportunity of seeing them feed, and of watching them carefully as they were eating the berries of the cedars, and in their habits and cries they seemed closely to resemble Jays. A specimen, previously killed, was found with its crop filled with the seeds of the yellow pine.

Dr. Cooper has seen specimens of this bird from Washoe, just east of the California State line, and he was informed by Mr. Clarence King that they frequent the junipers on mountains near Mariposa.

From Dr. Coues we learn that this bird is very abundant at Fort Whipple, where it remains all the year. It breeds in the retired portions of the neighboring mountains of San Francisco and Bill Williams, the young leaving the nest in July. As the same birds are ready to fly in April, at Carson City, it may be that they have two broods in Arizona. During the winter they collect in immense flocks, and in one instance Dr. Coues estimates their number at a thousand or more. In a more recent contribution to the Ibis (April, 1872), Dr. Coues gives a more full account of his observations in respect to this bird. In regard to geographical range he considers its distribution very nearly the same with that of the Picicorvus. Mr. Aiken has recently met with these birds in Colorado Territory, where, however, Mr. Allen did not obtain specimens. General McCall found these birds abundant near Santa Fé, in New Mexico, at an altitude Of seven thousand feet; and the late Captain Feilner obtained specimens at Fort Crook, in Northeastern California. Dr. Coues considers its range to be the coniferous zone of vegetation within the geographical area bounded eastward by the foot-hills and slopes of the Rocky Mountains; westward by the Cascade and Coast ranges; northward, perhaps to Sitka, but undetermined; and somewhat so southward, not traced so far as the tierra fria of Mexico.

Dr. Coues adds that, like most birds which subsist indifferently on varied animal or vegetable food, this species is not, strictly speaking, migratory, as it can find food in winter anywhere except at its loftiest points of distribution. A descent of a few thousand feet from the mountains thus answers all the purposes of a southward journey performed by other species, so far as food is concerned, while its hardy nature enables it to endure the rigors of winter. According to his observations, this bird feeds principally upon juniper berries and pine seeds, and also upon acorns and other small hard fruits.

Dr. Coues describes this bird as garrulous and vociferous, with curiously modulated chattering notes when at ease, and with extremely loud harsh cries when excited by fear or anger. It is also said to be restless and impetuous, as if of an unbalanced mind. Its attitudes on the ground, to which it frequently descends, are essentially Crow-like, and its gait is an easy walk or run, very different from the leaping manner of progress made by the Jays. When perching, its usual attitude is stiff and firm. Its flight resembles that of the Picicorvus. After breeding, these birds unite in immense flocks, but disperse again in pairs when the breeding-season commences.

Nothing, so far, has been published in regard to the character of the eggs.

Subfamily GARRULINÆ

Char. Wings short, rounded; not longer or much shorter than the tail, which is graduated, sometimes excessively so. Wings reaching not much beyond the lower tail-coverts. Bristly feathers at base of bill variable. Bill nearly as long as the head, or shorter. Tarsi longer than the bill or than the middle toe. Outer lateral claws rather shorter than the inner.

The preceding diagnosis may perhaps characterize the garruline birds, as compared with the Crows. The subdivisions of the group are as follows:—

A. Nostrils moderate, completely covered by incumbent feathers.

a. Tail much longer than the wings; first primary attenuated, falcate.

Pica. Head without crest.

b. Tail about as long as the wings; first primary not falcate.

Cyanura. Head with lengthened narrow crest. Wing and tail blue, banded with black.

Cyanocitta. Head without crest. Above blue, with a gray patch on the back. No bands on wing and tail.

Xanthoura. Head without crest. Color above greenish; the head blue; lateral tail-feathers yellow.

Perisoreus. Head full and bushy. Bill scarcely half the head, with white feathers over the nostrils. Plumage dull.

B. Nostrils very large, naked, uncovered by feathers.

Psilorhinus. Head not crested; tail broad; wings two thirds as long as the tail.

Calocitta. Head with a recurved crest; wings less than half as long as the tail.

There is a very close relationship between the Jays and the Titmice, the chief difference being in size rather than in any other distinguishing feature. The feathers at the base of the bill, however, in the Jays, are bristly throughout, with lateral branches reaching to the very tip. In Paridæ these feathers are inclined to be broader, with the shaft projecting considerably beyond the basal portion, or the lateral branches are confined to the basal portion, and extended forwards. There is no naked line of separation between the scutellæ on the outer side of the tarsi. The basal joint of the middle toe is united almost or quite to the end to the lateral, instead of half-way. The first primary is usually less than half the second, instead of rather more; the fourth and fifth primaries nearly equal and longest, instead of the fifth being longer than the fourth.

Genus PICA, CuvierCoracias, Linnæus, Syst. Nat. 1735 (Gray).

Pica, Brisson, Ornithologia, 1760, and of Cuvier (Agassiz). (Type, Corvus pica, L.)

Cleptes, Gambel, J. A. N. Sc. 2d Ser. I, 1847, 47.

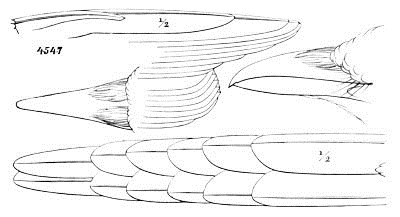

Gen. Char. Tail very long, forming much more than half the total length; the feathers much graduated; the lateral scarcely more than half the middle. First primary falcate, curved, and attenuated. Bill about as high as broad at the base; the culmen and gonys much curved, and about equal; the bristly feathers reaching nearly to the middle of the bill. Nostrils nearly circular. Tarsi very long; middle toe scarcely more than two thirds the length. A patch of naked skin beneath and behind the eye.

The peculiar characteristic of this genus, in addition to the very long graduated tail, lies in the attenuated, falcate first primary. Calocitta, which has an equally long or longer tail, has the first primary as in the Jays generally (besides having the nostrils exposed).

Pica hudsonica.

4547

A specimen of P. nuttalli has the lateral tarsal plates with two or three transverse divisions on the lower third. This has not been observed by us to occur in P. hudsonica.

Species and VarietiesP. caudata. Head, neck, breast, interscapulars, lining of wing, tail-coverts and tibiæ, deep black: wings metallic greenish-blue; tail rich metallic green, the feathers passing through bronze and reddish-violet into violet-blue, at their tips. Scapulars, abdomen, sides, flanks, and inner webs of primaries, pure white. Sexes alike; young similar.

a. Bill and bare space around the eye black.

Wing, 7.50; tail, 9.50 or less, its graduation less than half its length, 4.50; culmen, 1.20; tarsus, 1.75; middle toe, 1.05. Hab. Europe … var. caudata.55

Wing, over 8.00 (8.50 maximum); tail over 10.00 (13.50, max., its graduation more than half its length, 7.70); culmen, 1.55; tarsus, 1.75; middle toe, 1.05. Hab. Northern and Middle North America, exclusive of the Atlantic Province of United States and California … var. hudsonica.

b. Bill and bare space around the eye yellow.

Wing, 7.50; tail, 10.50; its graduation, 5.00; culmen, 1.50; tarsus, 1.75; middle toe, 1.05. Hab. California … var. nuttalli.

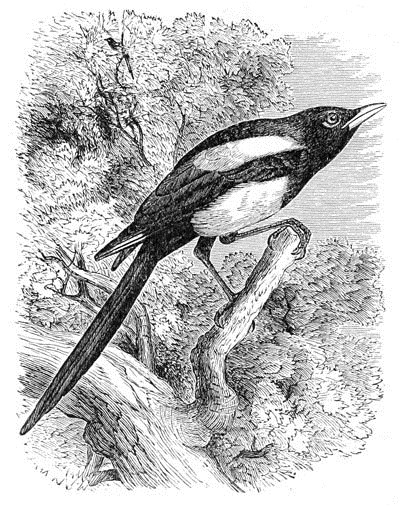

Pica caudata, var. hudsonica, BonapMAGPIECorvus pica, Forster, Phil. Trans. LXXII, 1772, 382.—Wilson, Am. Orn. IV, 1811, 75, pl. xxxv.—Bon. Obs. Wils. 1825, No. 40.—Ib. Syn. 1828, 57.—Nuttall, Man. I, 1832, 219.—Aud. Orn. Biog. IV, 1838, 408, pl. ccclvii (not of Linnæus). Corvus hudsonica, Jos. Sabine, App. Narr. Franklin’s Journey, 1823, 25, 671. Picus hudsonica, Bonap. List, 1838.—Ib. Conspectus, 1850, 383.—Maxim. Reise Nord Amer. I, 1839, 508.—Ib. Cabanis, Journ. 1856, 197.—Newberry, Zoöl. Cal. & Or. Route, Rep. P. R. R. VI, IV, 1857, 84.—Baird, Birds N. Am. 1858, 576, pl. xxv.—Lord, Pr. R. A. Inst. IV, 121 (British Columbia).—Cooper & Suckley, 213, pl. xxv.—Dall & Bannister, Trans. Chicago Acad. I, 1869, 286 (Alaska).—Finsch, Abh. Nat. III, 1872, 39 (Alaska).—Cooper, Orn. Cal. 1, 1870, 296. Cleptes hudsonicus, Gambel, J. A. N. Sc. 2d Ser. I, Dec. 1847, 47. Pica melanoleuca, “Vieill.” Aud. Syn. 1839, 157.—Ib. Birds Am. IV, 1842, 99, pl. ccxxvii.

Pica nuttalli.

Sp. Char. Bill and naked skin behind the eye black. General color black. The belly, scapulars, and inner webs of the primaries white; hind part of back grayish; exposed portion of the tail-feathers glossy green, tinged with purple and violet near the end; wings glossed with green; the secondaries and tertials with blue; throat-feathers spotted with white in younger specimens. Length, 19.00; wing, 8.50; tail, 13.00. Young in color and appearance similar generally to the adult.

Hab. The northern regions of North America. The middle and western Provinces of the United States exclusive of California; Wisconsin, Michigan, and Northern Illinois, in winter.

The American Magpie is almost exactly similar to the European, and differs only in larger size and disproportionably longer tail. According to Maximilian and other authors, the iris of the American bird has a grayish-blue outer ring, wanting in the European bird, and the voice is quite different. It is, however, difficult to consider the two birds otherwise than as geographical races of one primitive stock.

Habits. The American Magpie has an extended western distribution from Arizona on the south to Alaska on the northwest. It has been met with as far to the east as the Missouri River, and is found from there to the Pacific. It is abundant at Sitka; it was observed at Ounga, one of the Shumagin Islands, and was obtained by Bischoff at Kodiak.

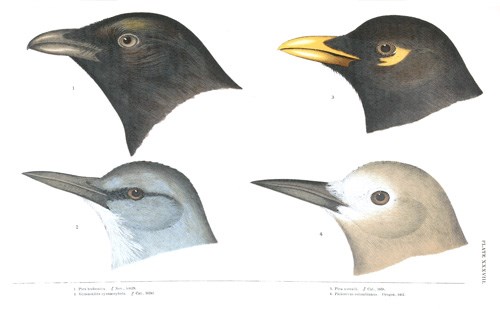

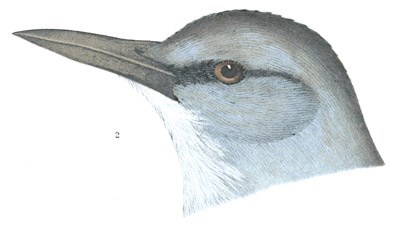

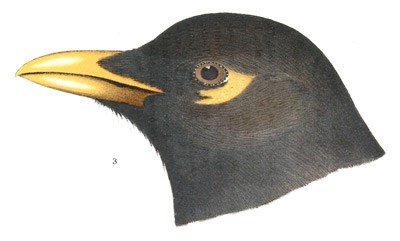

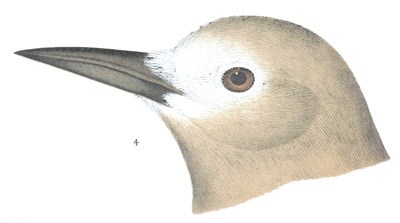

PLATE XXXVIII.

1. Pica hudsonica. ♂ Nev., 53629.

2. Gymnokitta cyanocephala. ♂ Cal., 16247.

3. Pica nuttalli. ♂ Cal., 3938.

4. Picicorvus columbianus. Oregon, 4461.

Richardson observed these birds on the Saskatchewan, where a few remain even in winter, but are much more frequent in summer.

Mr. Lord, the naturalist of the British branch of the Northwest Boundary Survey, characterizes our Magpie as murderous, because of its cruel persecution of galled and suffering mules, its picking out the eyes of living animals, and its destruction of birds. These birds caused so much trouble to the party, in winter, at Colville, as to become utterly unbearable, and a large number were destroyed by strychnine. They were then so tame and impudent that he repeatedly gave them food from his hand without their showing any evidence of fear. He says they nest in March.

Dr. Suckley states that this Magpie is abundant throughout the central region of Oregon and Washington Territory. He first met with it a hundred miles west of Fort Union, at the mouth of the Yellowstone. It became more abundant as the mountains were approached, and so continued almost as far west as the Cascade Mountains, where the dense forests were an effectual barrier. On Puget Sound he saw none until August, after which, during the fall, it was tolerably abundant. It breeds throughout the interior. He obtained a young bird, nearly fledged, about May 5, at Fort Dalles. At this place a few birds remain throughout the winter, but a majority retire farther south during the cold weather. One of its cries, he says, resembles a peculiar call of Steller’s Jay.

Mr. Ridgway regards this Magpie as one of the most characteristic and conspicuous birds of the interior region, distinguished both for the elegance of its form and the beauty of its plumage. While not at all rare in the fertile mountain cañons, the principal resort of this species is the rich bottom-land of the rivers. The usual note of the Magpie is a frequently uttered chatter, very peculiar, and, when once heard, easily recognized. During the nesting-season it utters a softer and more musical and plaintive note, sounding something like kay´-e-ehk-kay-e. It generally flies about in small flocks, and, like others of its family, is very fond of tormenting owls. In the winter, in company with the Ravens, it resorts to the slaughter-houses to feed on offal. The young differ but little in plumage from the adult, the metallic colors being even a little more vivid; the white spotting of the throat is characteristic of the immature bird.

The nests were found by Mr. Ridgway in various situations. Some were in cedars, some in willows, and others in low shrubs. In every instance the nest was domed, the inner and real nest being enclosed in an immense thorny covering, which far exceeded it in bulk. In the side of this thorny protection is a winding passage leading into the nest, possibly designed to conceal the very long tail of the bird, which, if exposed to view, would endanger its safety.

Dr. Cooper first met this bird east of the Cascade Mountains, near the Yakima, and from there in his journey northward as far as the 49th degree it was common, as well as in all the open unwooded regions until the mountains were passed on his return westward.

Dr. Kennerly met with these birds on the Little Colorado in New Mexico, in December. He found them in great numbers soon after leaving the Rio Grande, and from time to time on the march to California. They seemed to live indifferently in the deep cañons among the hills or in the valleys, but were only found near water.

Dr. Newberry first met with these birds on the banks of one of the tributaries of the Des Chutes, one hundred miles south of the Columbia, afterwards on the Columbia, but nowhere in large numbers. He regards them as much less gregarious in their habits than Pica nuttalli, as all the birds he noticed were solitary or in pairs, while the Yellow-bills were often seen in flocks of several hundreds.

All accounts of this bird agree in representing it as frequently a great source of annoyance to parties of exploration, especially in its attacks upon horses worn down and galled by fatigue and privations. In the memorable narrative of Colonel Pike’s journey in New Mexico, these birds, rendered bold and voracious by want, are described as assembling around that miserable party in great numbers, picking the sore backs of their perishing horses, and snatching at all the food they could reach. The party of Lewis and Clark, who were the first to add this bird to our fauna, also describe them as familiar and voracious, penetrating into their tents, snatching the meat even from their dishes, and frequently, when the hunters were engaged in dressing their game, seizing the meat suspended within a foot or two of their heads.

Mr. Nuttall, in his tour across the continent, found these birds so familiar and greedy as to be easily taken, as they approached the encampment for food, by the Indian boys, who kept them prisoners. They soon became reconciled to their confinement, and were continually hopping around and tugging and struggling for any offal thrown to them.

Observers have reported this bird from different parts of Arizona and New Mexico; but Dr. Coues writes me that he never saw it at Fort Whipple, or elsewhere in the first-named Territory. He found it breeding, however, in the Raton Mountains, in June, under the following circumstances, recorded at the time in his journal.

“Yesterday, the 8th, we were rolling over smooth prairie, ascending a little the while, but so gradually that only the change in the flora indicated the difference in elevation. The flowery verdure was passed, scrubby junipers came thicker and faster, and pine-clad mountain-tops took shape before us. We made the pass to-day, rounding along a picturesque ravine, and the noon halt gave me a chance to see something of the birds. Troops of beautiful Swallows were on wing, and as their backs turned in their wayward flight, the violet-green colors betrayed the species. A colony of them were breeding on the face of a cliff, apparently like H. lunifrons, but the nests were not accessible. Whilst I was watching their movements, a harsh scream attracted my attention, and the next moment a beautiful Magpie flew swiftly past with quivering wings, and with a flirt of the glittering tail and a curious evolution dashed into a dense thicket close by. In the hope of seeing him again, and perhaps of finding his nest, I hurried to the spot where he had disappeared, and pushed into the underbrush. In a few moments I stood in a little open space, surrounded on all sides and covered above with a network of vines interlacing the twigs and foliage so closely that the sun’s rays hardly struggled through. A pretty shady bower! and there, sure enough, was the nest, not likely to be overlooked, for it was as big as a bushel basket,—a globular mass, hung in the top of one of the taller saplings, about twelve feet from the ground. The mother bird was at home, and my bustling approach alarmed her; she flew out of the nest with loud cries of distress, which brought the male to her side in an instant. As I scrambled up the slender trunk, which swayed with my weight, both birds kept flying about my head with redoubled outcry, alighting for an instant, then dashing past again so close that I thought they would peck at me. As I had no means of preserving the nest, I would not take it down, and contented myself with such observations as I could make whilst bestriding a limb altogether too slender for comfort. It was nearly spherical in shape, seemed to be about eighteen inches in diameter, arched over, with a small hole on one side. The walls, composed entirely of interlaced twigs bristling outwardly in every direction, were extremely thick, the space inside being much less than one would expect, and seemingly hardly enough to accommodate the bird’s long tail, which I suppose must be held upright. The nest was lined with a little coarse dried grass, and contained six young ones nearly ready to fly. Authors state that the American Magpie lays only two eggs; but I suppose that this particular pair lived too far from scientific centres to find out what was expected of them. Other birds, noticed to-day, were Steller’s Jays among the pines and cedars, a flock of Chrysomitris, apparently pinus, feeding on willow-buds along the rivulet that threaded the gorge, and some Robins.”

The eggs of this Magpie are somewhat larger than any I have seen of P. nuttalli, and are differently marked and colored. Six specimens from the Sierra Nevada exhibit the following measurements: 1.40 × 0.98, 1.22 × 1.00, 1.41 × 0.95, 1.28 × 0.95, 1.26 × 0.92, 1.32 × 0.96. Their ground-color is a grayish-white, or light gray with a yellowish tinge, spotted with blotches, dottings, and dashes of a purplish or violet brown. In some they are sparsely distributed, showing plainly the ground, more confluent at the larger end. In others they are finer, more generally and more thickly distributed. In others they are much larger and of deeper color, and cover the whole of the larger end with one large cloud of confluent markings. None of these closely resembles the eggs of P. nuttalli. The usual number of eggs in a nest, according to Mr. Ridgway, varies from six to nine, although it is said that ten are sometimes found.

Pica caudata, var. nuttalli, AudYELLOW-BILLED MAGPIEPica nuttalli, Aud. Orn. Biog. IV, 1838, 450, pl. ccclxii.—Ib. Syn. 1839, 152.—Ib. Birds Am. IV, 1842, 104, pl. ccxxviii.—Bon. List, 1838.—Ib. Conspectus, 1850, 383.—Nuttall, Man. I, (2d ed.,) 1840, 236.—Newberry, Rep. P. R. R. VI, IV, 1857, 84.—Baird, Birds N. Am. 1858, 578, pl. xxvi.—Heerm. X, S, 54.—Cooper, Orn. Cal. I, 1870, 295. Cleptes nuttalli, Gambel, J. A. N. Sc. Ph. 2d Series, I, 1847, 46.

Sp. Char. Bill, and naked skin behind the eye, bright yellow; otherwise similar to P. hudsonica. Length, 17.00; wing, 8.00; tail. 10.00.

Hab. California (Sacramento Valley, and southern coast region).

We cannot look upon the Yellow-billed Magpie otherwise than as a local race of the common kind, since it is well known that among the Jays many species have the bill either black or yellow according to sex, age, or locality; and as the Yellow-billed Magpie occupies a more southern locality than usual, and one very different from that of the black-billed species, it well may exhibit a special geographical variation. The great restriction in range is another argument in favor of its being a simple variety.

Habits. The Yellow-billed Magpie seems to be exclusively a bird of California, where it is very abundant, and where it replaces almost entirely the more eastern form. Mr. Ridgway, who met with this variety only in the valley of the Sacramento, states that he there found it very abundant among the oaks of that region. It differed from the common Magpie in being exceedingly gregarious, moving about among the oak groves in small companies, incessantly chattering as it flew, or as it sat among the branches of the trees. He saw many of their nests in the tops of the oaks,—indeed, all were so situated,—yet he never met with the nests of the other species in a high tree, not even in the river valleys. The young of this Magpie have the white of the scapulars marked with rusty triangular spots.