полная версия

полная версияA History of North American Birds, Land Birds. Volume 2

“The nest is placed in the fork of a large bush or tree, sometimes at the height of twenty or thirty feet, and is a bulky structure, not distantly resembling a miniature Crow’s nest, but it is comparatively deeper and more compactly built. A great quantity of short, crooked twigs are brought together and interlaced to form the basement and outer wall, and with these is matted a variety of softer material, as weed-stalks, fibrous roots, and dried grasses. A little mud may be found mixed with the other material, but it is not plastered on in any quantity, and often seems to be merely what adhered to the roots or plant-stems that were used. The nest is finished inside with a quantity of hair. The eggs are altogether different from those of the Quiscali and Agelæi, and resemble those of the Yellow-headed and Rusty Grakles. They vary in number from four to six, and measure barely an inch in length by about three fourths as much in breadth. The ground-color is dull olivaceous-gray, sometimes a paler, clearer bluish or greenish gray, thickly spattered all over with small spots of brown, from very dark blackish-brown or chocolate to light umber. These markings, none of great size, are very irregular in outline, though probably never becoming line-tracery; and they vary indefinitely in number, being sometimes so crowded that the egg appears of an almost uniform brownish color.

“In this region the Blackbirds play the same part in nature’s economy that the Yellow-headed Troupial does in some other parts of the West, and the Cowbird and Purple Grakle in the East. Like others of their tribe they are very abundant where found at all, and eminently gregarious, except whilst breeding. Yet I never saw such innumerable multitudes together as the Redwinged Blackbird, or even its Californian congener, A. tricolor, shows in the fall, flocks of fifty or a hundred being oftenest seen. Unlike the Agelæi, they show no partiality for swampy places, being lovers of the woods and fields, and appearing perfectly at home in the clearings about man’s abode, where their sources of supply are made sure through his bounty or wastefulness. They are well adapted for terrestrial life by the size and strength of their feet, and spend much of their time on the ground, betaking themselves to the trees on alarm. On the ground they habitually run with nimble steps, when seeking food, only occasionally hopping leisurely, like a Sparrow, upon both feet at once. Their movements are generally quick, and their attitudes varied. They run with the head lowered and tail somewhat elevated and partly spread for a balance, but in walking slowly the head is held high, and oscillates with every step. The customary attitude when perching is with the body nearly erect, the tail hanging loosely down, and the bill pointing upward; but should their attention be attracted, this negligent posture is changed, the birds sit low and firmly, with elevated and wide-spread tail rapidly flirted, whilst the bright eye peers down through the foliage. When a flock comes down to the ground to search for food, they generally huddle closely together and pass pretty quickly along, each one striving to be first, and in their eagerness they continually fly up and re-alight a few paces ahead, so that the flock seems, as it were, to be rolling over and over. When disturbed at such times, they fly in a dense body to a neighboring tree, but then almost invariably scatter as they settle among the boughs. The alarm over, one, more adventurous, flies down again, two or three follow in his wake, and the rest come trooping after. In their behavior towards man, they exhibited a curious mixture of heedlessness and timidity; they would ramble about almost at our feet sometimes, yet the least unusual sound or movement sent them scurrying into the trees. They became tamest about the stables, where they would walk almost under the horses’ feet, like Cowbirds in a farm-yard.

“Their hunger satisfied, the Blackbirds would fly into the pine-trees and remain a long time motionless, though not at all quiet. They were at singing-school,’ we used to say, and certainly there was room for improvement in their chorus; but if their notes were not particularly harmonious, they were sprightly, varied, and on the whole rather agreeable, suggesting the joviality that Blackbirds always show when their stomachs are full, and the prospect of further supply is good. Their notes are rapid and emphatic, and, like the barking of coyotes, give an impression of many more performers than are really engaged. They have a smart chirp, like the clashing of pebbles, frequently repeated at intervals, varied with a long-drawn mellow whistle. Their ordinary note, continually uttered when they are searching for food, is intermediate between the guttural chuck of the Redwing and the metallic chink of the Reedbird.

“In the fall, when food is most abundant, they generally grow fat, and furnish excellent eating. They are tender, like other small birds, and do not have the rather unpleasant flavor that the Redwing gains by feeding too long upon the Zizania.

“These are sociable as well as gregarious birds, and allied species are seen associating with them. At Wilmington, Southern California, where I found them extremely abundant in November, they were flocking indiscriminately with the equally plentiful Agelaius tricolor.”

Dr. Heermann found this Blackbird very common in New Mexico and Texas, though he was probably in error in supposing that all leave there before the period of incubation. During the fall they frequent the cattle-yards, where they obtain abundance of food. They were very familiar, alighting on the house-tops, and apparently having no cause for fear of man. Unlike all other writers, he speaks of its song as a soft, clear whistle. When congregated in spring on the trees, they keep up a continual chattering for hours, as though revelling in an exuberance of spirits.

Under the common Spanish name of Pajaro prieto, Dr. Berlandier refers in MSS. to this species. It is said to inhabit the greater part of Mexico, and especially the Eastern States. It moves in flocks in company with the other Blackbirds. It is said to construct a well-made nest about the end of April, of blades of grass, lining it with horse-hair. The eggs, three or four in number, are much smaller than those of Quiscalus macrurus, obtuse at one end, and slightly pointed at the other. The ground-color is a pale gray, with a bluish tint, and although less streaked, bears a great resemblance to those of the larger Blackbird.

Dr. Cooper states that these birds nest in low trees, often several in one tree. He describes the nest as large, constructed externally of a rough frame of twigs, with a thick layer of mud, lined with fine rootlets and grasses. The eggs are laid from April 10 to May 20, are four or five in number, have a dull greenish-white ground, with numerous streaks and small blotches of dark brown. He gives their measurement at one inch by .72. They raise two and probably three broods in a season.

Four eggs of this species, from Monterey, collected by Dr. Canfield, have an average measurement of 1.02 inches by .74. Their ground-color is a pale white with a greenish tinge. They are marked with great irregularity, with blotches of a light brown, with fewer blotches of a much darker shade, and a few dots of the same. In one egg the spots are altogether of the lighter shade, and are so numerous and confluent as to conceal the ground-color. In the other they are more scattered, but the lines and marbling of irregularly shaped and narrow zigzag marking are absent in nearly all the eggs.

Mr. Lord found this species a rare bird in British Columbia. He saw a few on Vancouver Island in the yards where cattle were fed, and a small number frequented the mule-camp on the Sumas prairie. East of the Cascades he met none except at Colville, where a small flock had wintered in a settler’s cow-yard. They appeared to have a great liking for the presence of those animals, arising from their finding more food and insects there than elsewhere, walking between their legs, and even perching upon their backs.

Captain Blakiston found this species breeding on the forks of the Saskatchewan, June 3, 1858, where he obtained its eggs.

Genus QUISCALUS, VieillotQuiscalus, Vieillot, Analyse, 1816 (Gray). (Type, Gracula quiscala, L.)

Quiscalus purpureus.

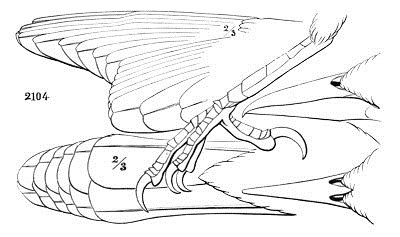

2104

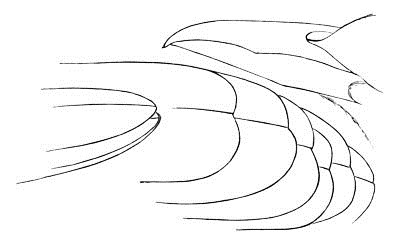

Sp. Char. Bill as long as the head, the culmen slightly curved, the gonys almost straight; the edges of the bill inflected and rounded; the commissure quite strongly sinuated. Outlines of tarsal scutellæ well defined on the sides; tail long, boat-shaped, or capable of folding so that the two sides can almost be brought together upward, the feathers conspicuously and decidedly graduated, their inner webs longer than the outer. Color black.

The excessive graduation of the long tail, with the perfectly black color, at once distinguishes this genus from any other in the United States. Two types may be distinguished: one Quiscalus, in which the females are much like the males, although a little smaller and perhaps with rather less lustre; the other, Megaquiscalus, much larger, with the tail more graduated, the females considerably smaller, and of a brown or rusty color. The Quiscali are all from North America or the West Indies (including Trinidad); none having been positively determined as South American. The Megaquiscali are Mexican and Gulf species entirely, while a third group, the Holoquiscali, is West Indian.

Synopsis of Species and VarietiesA. QUISCALUS. Sexes nearly similar in plumage. Color black; each species glossed with different shades of bronze, purple, violet, green, etc. Lateral tail-feathers about .75 the length of central. Hab. Eastern United States. Proportion of wing to tail variable.

Q. purpureus. a. Body uniform brassy-olive without varying tints. Head and neck steel-blue, more violaceous anteriorly.

1. Length, 13.50; wing, 5.50 to 5.65; tail, 5.70 to 5.80, its graduation, 1.50; culmen, 1.35 to 1.40. Vivid blue of the neck all round abruptly defined against the brassy-olive of the body. Female. Wing, 5.20; tail, 4.85 to 5.10. Hab. Interior portions of North America, from Texas and Louisiana to Saskatchewan and Hudson’s Bay Territory; New England States; Fort Bridger, Wyoming Territory … var. æneus.

b. Body variegated with purple, green, and blue tints. Head and neck violaceous-purple, more blue anteriorly.

2. Length, 12.50; wing, 5.60; tail, 5.30, its graduation, 1.20; culmen, 1.32. Dark purple of neck all round passing over the breast, and appearing in patches on the lower parts. Wing and tail purplish; tail-coverts reddish-purple. Female. Wing, 5.10; tail, 4.50. Hab. Atlantic coast of United States … var. purpureus.

3. Length, 11.75; wing, 4.85 to 5.60; tail, 4.60 to 5.50, its graduation, .90; culmen, 1.38 to 1.66. Dark purple of neck sharply defined against the dull blackish olive-green of the body. Wings and tail greenish-blue; tail-coverts violet-blue. Female. Wing, 4.65 to 4.90; tail, 3.80 to 4.60. Hab. South Florida; resident … var. agelaius.

B. HOLOQUISCALUS. (Cassin.) Tail shorter than wings; sexes similar. Color glossy black, but without varying shades of gloss; nearly uniform in each species. Tail moderately graduated. Hab. West India Islands, almost exclusively; Mexico and South America.

Q. baritus. Black, with a soft bluish-violet gloss, changing on wings and tail into bluish-green.

Culmen decidedly curved; base of mandibles on sides, smooth1. Bill robust, commissure sinuated; depth of bill, at base, .54; culmen, 1.33; wing, 6.15; tail, 5.50, its graduation, 1.30. Female. Wing, 5.20; tail, 4.70; other measurements in proportion. Hab. Jamaica … var. baritus.43

2. Bill slender, commissure scarcely sinuated; depth of bill, .43; culmen, 1.35; wing, 5.40; tail, 5.10, its graduation, 1.20. Female. Wing, 4.60; tail, 4.20. Hab. Porto Rico … var. brachypterus.44

Culmen almost straight; base of mandibles on sides corrugated3. Depth of bill, .51; culmen, 1.44; wing, 6.00; tail, 5.50, its graduation, 1.50. Female. Wing, 5.15; tail, 4.80. Hab. Cuba … var. gundlachi.45

4. Depth of bill, .40; culmen, 1.35; wing, 5.00; tail, 4.50, its graduation, .85. Hab. Hayti … var. niger.46

C. MEGAQUISCALUS. (Cassin.) Tail longer than wings. Sexes very unlike. Female much smaller, and very different in color, being olivaceous-brown, lightest beneath. Male without varying shades of color; lateral tail-feather about .60 the middle, or less.

Q. major. Culmen strongly decurved terminally; bill robust. Female with back, nape, and crown like the wings; abdomen much darker than throat.

Lustre of the plumage green, passing into violet anteriorly on head and neck1. Length, 15.00; wing, 7.50; tail, 7.70, its graduation, 2.50; culmen, 1.60. Female. Wing, 5.10. Hab. South Atlantic and Gulf coast of United States … var. major.

Lustre, violet passing into green posteriorly2. Length, 14.00; wing, 6.75; tail, 7.20, its graduation, 2.40; culmen, 1.57. Female. Wing, 5.30; tail, 5.00. Hab. Western Mexico. (Mazatlan, Colima, etc.) … var. palustris.47

3. Length, 18.00; wing, 7.70; tail, 9.20, its graduation, 3.50; culmen, 1.76. Female. Wing, 5.80; tail, 6.30. Hab. From Rio Grande of Texas, south through Eastern Mexico; Mazatlan (accidental?) … var. macrurus.

Q. tenuirostris. 48 Culmen scarcely decurved terminally; bill slender. Female with back, nape, and crown very different in color from the wings; abdomen as light as throat.

1. Male. Lustre purplish-violet, inclining to steel-blue on wing and upper tail-coverts. Length, 15.00; wing, 7.00; tail, 8.00, its graduation, 3.00. Female. Crown, nape, and back castaneous-brown; rest of upper parts brownish-black. A distinct superciliary stripe, with the whole lower parts as far as flanks and crissum, deep fulvous-ochraceous, lightest, and inclining to ochraceous-white, on throat and lower part of abdomen; flanks and crissum blackish-brown. Wing, 5.10; tail, 5.35, its graduation, 1.80; culmen, 1.33; greatest depth of bill, .36. Hab. Mexico (central?).

Quiscalus purpureus, BartrTHE CROW BLACKBIRD

Quiscalus purpureus.

Sp. Char. Bill above, about as long as the head, more than twice as high; the commissure moderately sinuated and considerably decurved at tip. Tail a little shorter than the wing, much graduated, the lateral feathers .90 to 1.50 inches shorter. Third quill longest; first between fourth and fifth. Color black, variously glossed with metallic reflections of bronze, purple, violet, blue, and green. Female similar, but smaller and duller, with perhaps more green on the head. Length, 13.00; wing, 6.00; bill above, 1.25.

Hab. From Atlantic to the high Central Plains.

Of the Crow Blackbird of the United States, three well-marked races are now distinguished in the species: one, the common form of the Atlantic States; another occurring in the Mississippi Valley, the British Possessions, and the New England States, and a third on the Peninsula of Florida. The comparative diagnoses of the three will be found on page 809.

Var. purpureus, BartramPURPLE GRAKLEGracula quiscala, Linn. Syst. Nat. I, (ed. 10,) 1758, 109 (Monedula purpurea, Cal.); I, (ed. 12,) 1766, 165.—Gmelin, I, 1788, 397.—Latham, Ind. I, 1790, 191.—Wilson, Am. Orn. III, 1811, 44, pl. xxi, f. 4. Chalcophanes quiscalus, Wagler, Syst. Av. 1827 (Gracula).—Cab. Mus. Hein. 1851, 196. ? ? Oriolus ludovicianus, Gmelin, Syst. Nat. I, 1788, 387; albino var. ? ? Oriolus niger, Gmelin, Syst. Nat. I, 1788, 393. ? Gracula purpurea, Bartram, Travels, 1791, 290. Quiscalus versicolor, Vieillot, Analyse? 1816.—Ib. Nouv. Dict. XXVIII, 1819, 488.—Ib. Gal. Ois. I, 171, pl. cviii.—Bon. Obs. Wils. 1824, No. 45.—Ib. Am. Orn. I, 1825, 45, pl. v.—Ib. List, 1838.—Ib. Conspectus, 1840, 424.—Sw. F. Bor.-Am. II, 1831, 485.—Nuttall, Man. I, 1832, 194.—Aud. Orn. Biog. I, 1831, 35; V, 1838, 481 (not the pl. vii.).—Ib. Syn. 1839, 146.—Ib. Birds Am. IV, 1842, 58 (not the pl. ccxxi.).—Baird, Birds N. Am. 1858, 575. Gracula barita, Ord., J. A. N. Sc. I, 1818, 253. “Quiscalus purpureus, Licht.”—Cassin, Pr. A. N. Sc., 1866, 403.—Ridgway, Pr. A. N. S. 1869, 133.—Allen, B. E. Fla. 291 (in part). Quiscalus nitens, Licht. Verz. 1823, No. 164. Quiscalus purpuratus, Swainson, Anim. in Menag. 1838, No. 55. Purple Grakle, Pennant, Arctic Zoöl. II.

Sp. Char. Length about 12.50; wing, 5.50; tail, 4.92; culmen, 1.24; tarsus, 1.28. Second quill longest, hardly perceptibly (only .07 of an inch) longer than the first and third, which are equal; projection of primaries beyond secondaries, 1.56; graduation of tail, .92. General appearance glossy black; whole plumage, however, brightly glossed with reddish-violet, bronzed purple, steel-blue, and green; the head and neck with purple prevailing, this being in some individuals more bluish, in others more reddish; where most blue this is purest anteriorly, becoming more violet on the neck. On other portions of the body the blue and violet forming an iridescent zone on each feather, the blue first, the violet terminal; sometimes the head is similarly marked. On the abdomen the blue generally predominates, on the rump the violet; wings and tail black, with violet reflection, more bluish on the latter; the wing-coverts frequently tipped with steel-blue or violet. Bill, tarsi, and toes pure black; iris sulphur-yellow.

Hab. Atlantic States, north to Nova Scotia, west to the Alleghanies.

Var. purpureus.

This form is more liable to variation than any other, the arrangement of the metallic tints varying with the individual; there is never, however, an approach to the sharp definition and symmetrical pattern of coloration characteristic of the western race.

The female is a little less brilliant than the male, and slightly smaller. The young is entirely uniform slaty-brown, without gloss.

An extreme example of this race (22,526, Washington, D. C.?) is almost wholly of a continuous rich purple, interrupted only on the interscapulars, where, anteriorly, the purple is overlaid by bright green, the feathers with terminal transverse bars of bluish. On the lower parts are scattered areas of a more bluish tint. The purple is richest and of a reddish cast on the neck, passing gradually into a bluish tint toward the bill; on the rump and breast the purple has a somewhat bronzy appearance.

Habits. The common Crow Blackbird of the eastern United States exhibits three well-marked and permanently varying forms, which we present as races. Yet these variations are so well marked and so constant that they almost claim the right to be treated as specifically distinct. We shall consider them by themselves. They are the Purple Grakle, or common Crow Blackbird, Quiscalus purpureus; the Bronzed Grakle, Q. æneus; and the Florida Grakle, Q. aglæus.

The first of these, the well-known Crow Blackbird of the Atlantic States, so far as we are now informed, has an area extending from Northern Florida on the south to Maine, and from the Atlantic to the Alleghanies. Mr. Allen states that the second form is the typical form of New England, but my observations do not confirm his statement. Both the eastern and the western forms occur in Massachusetts, but the purpureus alone seems to be a summer resident, the æneus occurring only in transitu, and, so far as I am now aware, chiefly in the fall.

The Crow Blackbirds visit Massachusetts early in March and remain until the latter part of September, those that are summer residents generally departing before October. They are not abundant in the eastern part of the State, and breed in small communities or by solitary pairs.

In the Central States, especially in Pennsylvania and New Jersey, they are much more abundant, and render themselves conspicuous and dreaded by the farmers through the extent of their depredations on the crops. The evil deeds of all birds are ever much more noticed and dwelt upon than their beneficial acts. So it is, to an eminent degree, with the Crow Blackbird. Very few seem aware of the vast amount of benefit it confers on the farmer, but all know full well—and are bitterly prejudiced by the knowledge—the extent of the damages this bird causes.

They return to Pennsylvania about the middle of March, in large, loose flocks, at that time frequenting the meadows and ploughed fields, and their food then consists almost wholly of grubs, worms, etc., of which they destroy prodigious numbers. In view of these services, and notwithstanding the havoc they commit on the crops of Indian corn, Wilson states that he should hesitate whether to consider these birds most as friends or as enemies, as they are particularly destructive to almost all the noxious worms, grubs, and caterpillars that infest the farmer’s fields, which, were they to be allowed to multiply unmolested, would soon consume nine tenths of all the productions of his labor, and desolate the country with the miseries of famine.

The depredations committed by these birds are almost wholly upon Indian corn, at different stages. As soon as its blades appear above the ground, after it has been planted, these birds descend upon the fields, pull up the tender plant, and devour the seeds, scattering the green blades around. It is of little use to attempt to drive them away with the gun. They only fly from one part of the field to another. And again, as soon as the tender corn has formed, these flocks, now replenished by the young of the year, once more swarm in the cornfields, tear off the husks, and devour the tender grains. Wilson has seen fields of corn in which more than half the corn was thus ruined.

These birds winter in immense numbers in the lower parts of Virginia, North and South Carolina, and Georgia, sometimes forming one congregated multitude of several hundred thousands. On one occasion Wilson met, on the banks of the Roanoke, on the 20th of January, one of these prodigious armies of Crow Blackbirds. They rose, he states, from the surrounding fields with a noise like thunder, and, descending on the length of the road before him, they covered it and the fences completely with black. When they again rose, and after a few evolutions descended on the skirts of the high timbered woods, they produced a most singular and striking effect. Whole trees, for a considerable extent, from the top to the lowest branches, seemed as if hung with mourning. Their notes and screaming, he adds, seemed all the while like the distant sounds of a great cataract, but in a more musical cadence.

A writer in the American Naturalist (II. 326), residing in Newark, N. Y., notes the advent of a large number of these birds to his village. Two built their nest inside the spire of a church. Another pair took possession of a martin-house in the narrator’s garden, forcibly expelling the rightful owners. These same birds also attempted to plunder the newly constructed nests of the Robins of their materials. They were, however, successfully resisted, the Robins driving the Blackbirds away in all cases of contest.

The Crow Blackbird nests in various situations, sometimes in low bushes, more frequently in trees, and at various heights. A pair, for several years, had their nest on the top of a high fir-tree, some sixty feet from the ground, standing a few feet from my front door. Though narrowly watched by unfriendly eyes, no one could detect them in any mischief. Not a spear of corn was molested, and their food was exclusively insects, for which they diligently searched, turning over chips, pieces of wood, and loose stones. Their nests are large, coarsely but strongly made of twigs and dry plants, interwoven with strong stems of grasses. When the Fish Hawks build in their neighborhood, Wilson states that it is a frequent occurrence for the Grakles to place their nests in the interstices of those of the former. Sometimes several pairs make use of the same Hawk’s nest at the same time, living in singular amity with its owner. Mr. Audubon speaks of finding these birds generally breeding in the hollows of trees. I have never met with their nests in these situations, but Mr. William Brewster says he has found them nesting in this manner in the northern part of Maine. Both, however, probably refer to the var. æneus.