полная версия

полная версияA History of North American Birds, Land Birds. Volume 2

Mr. Lord found this bird by no means an abundant species in British Columbia. Those that were seen seemed to prefer the localities where the scrub-oaks grew, to the pine regions. He found their long, pendulous nests suspended from points of oak branches, without any attempt at concealment. He never met with any of these birds north of Fraser’s River, and very rarely east of the Cascades. A few stragglers visited his quarters at Colville, arriving late in May and leaving early in September, the males usually preceding the females three or four days.

On the Shasta Plains Mr. Lord noticed, in the nesting of this bird, a singular instance of the readiness with which birds alter their habits under difficulties. A solitary oak stood by a little patch of water, both removed by many miles from other objects of the kind. Every available branch and spray of this tree had one of the woven nests of this brilliant bird hanging from it, though hardly known to colonize elsewhere in this manner.

Dr. Coues, in an interesting paper on the habits of this species in the Naturalist for November, 1871, states that its nests, though having a general resemblance in their style of architecture, differ greatly from one another, usually for obvious reasons, such as their situation, the time taken for their construction, and even the taste and skill of the builders. He describes one nest, built in a pine-tree, in which, in a very ingenious manner, these birds bent down the long, straight, needle-like leaves of the stiff, terminal branchlets, and, tying their ends together, made them serve as the upper portion of the nest, and a means of attachment. This nest was nine inches long and four in diameter.

Another nest, described by the same writer, was suspended from the forked twig of an oak, and draped with its leaves, almost to concealment. It had an unusual peculiarity of being arched over and roofed in at the top, with a dome of the same material as the rest of the nest, and a small round hole on one side, just large enough to admit the birds.

The eggs of this Oriole are slightly larger than those of the Baltimore, and their ground-color is more of a creamy-white, yet occasionally with a distinctly bluish tinge. They are marbled and marked with irregular lines and tracings of dark umber-brown, deepening almost into black, but never so deep as in the eggs of the eastern species. These marblings vary constantly and in a remarkable degree; in some they are almost entirely wanting. They measure .90 of an inch in length by .65 in breadth.

Subfamily QUISCALINÆ

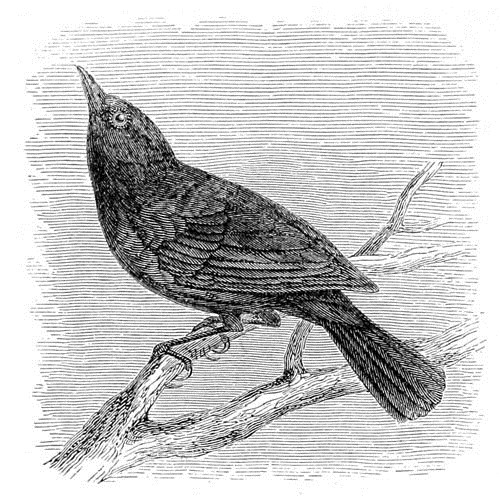

Scolecophagus ferrugineus.

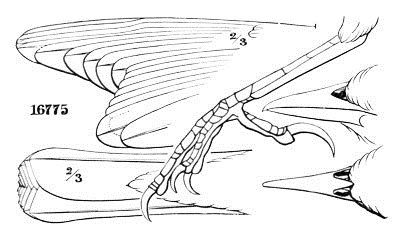

16775

Char. Bill rather attenuated, as long as or longer than the head. The culmen curved, the tip much bent down. The cutting edges inflected so as to impart a somewhat tubular appearance to each mandible. The commissure sinuated. Tail longer than the wings, usually much graduated. Legs longer than the head, fitted for walking. Color of males entirely black with lustrous reflections.

The bill of the Quiscalinæ is very different from that of the other Icteridæ, and is readily recognized by the tendency to a rounding inward along the cutting edges, rendering the width in a cross section of the bill considerably less along the commissure than above or below. The culmen is more curved than in the Agelainæ. All the North American species have the iris white.

The only genera in the United States are as follows:—

Scolecophagus. Tail shorter than the wings; nearly even. Bill shorter than the head.

Quiscalus. Tail longer than the wings; much graduated. Bill as long as or longer than the head.

Genus SCOLECOPHAGUS, SwainsonScolecophagus, Swainson, F. Bor.-Am. II, 1831. (Type, Oriolus ferrugineus, Gmelin.)

Gen. Char. Bill shorter than the head, rather slender, the edges inflexed as in Quiscalus, which it otherwise greatly resembles; the commissure sinuated. Culmen rounded, but not flattened. Tarsi longer than the middle toe. Tail even, or slightly rounded.

The above characteristics will readily distinguish the genus from its allies. The form is much like that of Agelaius. The bill, however, is more attenuated, the culmen curved and slightly sinuated. The bend at the base of the commissure is shorter. The culmen is angular at the base posterior to the nostrils, instead of being much flattened, and does not extend so far behind. The two North American species may be distinguished as follows:—

Synopsis of SpeciesS. ferrugineus. Bill slender; height at base not .4 the total length. Color of male black, with faint purple reflection over whole body; wings, tail, and abdomen glossed slightly with green. Autumnal specimens with feathers broadly edged with castaneous rusty. Female brownish dusky slate, without gloss; no trace of light superciliary stripe.

S. cyanocephalus. Bill stout; height at base nearly .5 the total length. Color black, with green reflections over whole body. Head only glossed with purple. Autumnal specimens, feathers edged very indistinctly with umber-brown. Female dusky-brown, with a soft gloss; a decided light superciliary stripe.

Cuba possesses a species referred to this genus (S. atroviolaceus), though it is not strictly congeneric with the two North American ones. It differs in lacking any distinct membrane above the nostril, and in having the bill not compressed laterally, as well as in being much stouter. The plumage has a soft silky lustre; the general color black, with rich purple or violet lustre. The female similarly colored to the male.

Scolecophagus ferrugineus, SwainsonRUSTY BLACKBIRDOriolus ferrugineus, Gmelin, Syst. Nat. I, 393, No. 43.—Lath. Ind. I, 1790, 176. Gracula ferruginea, Wilson, Am. Orn. III, 1811, 41, pl. xxi, f. 3. Quiscalus ferrugineus, Bon. Obs. Wils. 1824, No. 46.—Nuttall, Man. I, 1832, 199.—Aud. Orn. Biog. II, 1834, 315; V, 1839, 483, pl. cxlvii.—Ib. Synopsis, 1839, 146.—Ib. Birds Am. IV, 1842, 65, pl. ccxxii.—Max. Caban. J. VI, 1858, 204. Scolecophagus ferrugineus, Swainson, F. Bor.-Am. II, 1831, 286.—Bon. List, 1838.—Baird, Birds N. Am. 1858, 551.—Coues, P. A. N. S. 1861, 225.—Cass. P. A. N. S. 1866, 412.—Dall & Bannister, Tr. Ch. Ac. I, 1869, 285 (Alaska). ? ? Oriolus niger, Gmelin, I, 1788, 393, Nos. 4, 5 (perhaps Quiscalus).—Samuels, 350.—Allen, B. E. Fla. 291. Scolecophagus niger, Bonap. Consp. 1850, 423.—Cabanis, Mus. Hein. 1851, 195. ? ? Oriolus fuscus, Gmelin, Syst. I, 1788, 393, No. 44 (perhaps Molothrus). Turdus hudsonius, Gmelin, Syst. Nat. I, 1788, 818.—Lath. Ind. Turdus noveboracensis, Gmelin, I, 1788, 818. Turdus labradorius, Gmelin, Syst. Nat. I, 1788, 832.—Lath. Ind. I, 1790, 342 (labradorus). “Pendulinus ater, Vieillot, Nouv. Dict.” Chalcophanes virescens, Wagler, Syst. Av. (Appendix, Oriolus 9). ? Turdus No. 22 from Severn River, Forster Phil. Trans. LXII, 1772, 400.

Sp. Char. Bill slender; shorter than the head; about equal to the hind toe; its height not quite two fifths the total length. Wing nearly an inch longer than the tail; second quill longest; first a little shorter than the fourth. Tail slightly graduated; the lateral feathers about a quarter of an inch shortest. General color black, with purple reflections; the wings, under tail-coverts, and hinder part of the belly, glossed with green. In autumn the feathers largely edged with ferruginous or brownish, so as to change the appearance entirely. Spring female dull, opaque plumbeous or ashy-black; the wings and tail sometimes with a green lustre. Young like autumnal birds. Length of male, 9.50; wing, 4.75; tail, 4.00. Female smaller.

Hab. From Atlantic coast to the Missouri. North to Arctic regions. In Alaska on the Yukon, at Fort Kenai, and Nulato.

Scolecophagus ferrugineus.

Habits. The Rusty Blackbird is an eastern species, found from the Atlantic to the Missouri River, and from Louisiana and Florida to the Arctic regions. In a large portion of the United States it is only known as a migratory species, passing rapidly through in early spring, and hardly making a longer stay in the fall. Richardson states that the summer range of this bird extends to the 68th parallel, or as far as the woods extend. It arrives at the Saskatchewan in the end of April, and at Great Bear Lake, latitude 65°, by the 3d of May. They come in pairs, and for a time frequent the sandy beaches of secluded lakes, feeding on coleopterous insects. Later in the season they are said to make depredations upon the grain-fields.

They pass through Massachusetts from the 8th of March to the first of April, in irregular companies, none of which make any stay, but move hurriedly on. They begin to return early in October, and are found irregularly throughout that month. They are unsuspicious and easily approached, and frequent the streams and edges of ponds during their stay.

Mr. Boardman states that these birds are common near Calais, Me., arriving there in March, some remaining to breed. In Western Massachusetts, according to Mr. Allen, they are rather rare, being seen only occasionally in spring and fall as stragglers, or in small flocks. Mr. Allen gives as their arrival the last of September, and has seen them as late as November 24. They also were abundant in Nova Scotia. Dr. Coues states that in South Carolina they winter from November until March.

These birds are said to sing during pairing-time, and become nearly silent while rearing their young, but in the fall resume their song. Nuttall has heard them sing until the approach of winter. He thinks their notes are quite agreeable and musical, and much more melodious than those of the other species.

During their stay in the vicinity of Boston, they assemble in large numbers, to roost in the reed marshes on the edges of ponds, and especially in those of Fresh Pond, Cambridge. They feed during the day chiefly on grasshoppers and berries, and rarely molest the grain.

According to Wilson, they reach Pennsylvania early in October, and at this period make Indian corn their principal food. They leave about the middle of November. In South Carolina he found them numerous around the rice plantations, feeding about the hog-pens and wherever they could procure corn. They are easily domesticated, becoming very familiar in a few days, and readily reconciled to confinement.

In the District of Columbia, Dr. Coues found the Rusty Grakle an abundant and strictly gregarious winter resident, arriving there the third week in October and remaining until April, and found chiefly in swampy localities, but occasionally also in ploughed fields.

Mr. Audubon found these birds during the winter months, as far south as Florida and Lower Louisiana, arriving there in small flocks, coming in company with the Redwings and Cowbirds, and remaining associated with them until the spring. At this season they are also found in nearly all the Southern and Western States. They appear fond of the company of cattle, and are to be seen with them, both in the pasture and in the farm-yard. They seem less shy than the other species. They also frequent moist places, where they feed upon aquatic insects and small snails, for which they search among the reeds and sedges, climbing them with great agility.

In their habits they are said to resemble the Redwings, and, being equally fond of the vicinity of water, they construct their nests in low trees and bushes in moist places. Their nests are said to be similarly constructed, but smaller than those of the Redwings. In Labrador Mr. Audubon found them lined with mosses instead of grasses. In Maine they begin to lay about the first of June, and in Labrador about the 20th, and raise only one brood in a season.

The young, when first able to fly, are of a nearly uniform brown color. Their nests, according to Audubon, are also occasionally found in marshes of tall reeds of the Typha, to the stalks of which they are firmly attached by interweaving the leaves of the plant with grasses and fine strips of bark. A friend of the same writer, residing in New Orleans, found one of these birds, in full plumage and slightly wounded, near the city. He took it home, and put it in a cage with some Painted Buntings. It made no attempt to molest his companions, and they soon became good friends. It sang during its confinement, but the notes were less sonorous than when at liberty. It was fed entirely on rice.

The memoranda of Mr. MacFarlane show that these birds are by no means uncommon near Fort Anderson. A nest, found June 12, on the branch of a spruce, next to the trunk, was eight feet from the ground. Another nest, containing one egg and a young bird, was in the midst of a branch of a pine, five feet from the ground. The parents endeavored to draw him from their nest, and to turn his attention to themselves. A third, found June 22, contained four eggs, and was similarly situated. The eggs contained large embryos. Mr. MacFarlane states that whenever a nest of this species is approached, both parents evince great uneasiness, and do all in their power, by flying from tree to tree in its vicinity, to attract one from the spot. They are spoken of as moderately abundant at Fort Anderson, and as having been met with as far east as the Horton River. He was also informed by the Eskimos that they extend along the banks of the Lower Anderson to the very borders of the woods.

Mr. Dall states that these Blackbirds arrive at Nulato about May 20, where they are tolerably abundant and very tame. They breed later than some other birds, and had not begun to lay before he left, the last of May. Eggs were procured at Fort Yukon by Mr. Lockhart, and at Sitka by Mr. Bischoff.

Besides these localities, this bird was found breeding in the Barren Grounds of Anderson River in 69° north latitude, on the Arctic coast at Fort Kenai, by Mr. Bischoff, and at Fort Simpson, Fort Rae, and Peel River. It has been found breeding at Calais by Mr. Boardman, and at Halifax by Mr. W. G. Winton.

Eggs sent from Fort Yukon, near the mouth of the Porcupine River, by Mr. S. Jones, are of a rounded-oval shape, measuring 1.03 inches in length by .75 in breadth. In size, shape, ground-color, and color of their markings, they are hardly distinguishable from some eggs of Brewer’s Blackbird, though generally different. All I have seen from Fort Yukon have a ground-color of very light green, very thickly covered with blotches and finer dottings of a mixture of ferruginous and purplish-brown. In some the blotches are larger and fewer than in others, and in all these the purple shading predominates. One egg, more nearly spherical than the rest, measures .98 by .82. None have any waving lines, as in all other Blackbird’s eggs. Two from near Calais, Me., measure 1.02 by .75 of an inch, have a ground of light green, only sparingly blotched with shades of purplish-brown, varying from light to very dark hues, but with no traces of lines or marbling.

According to Mr. Boardman, these birds are found during the summer months about Calais, but they are not common. Only a few remain of those that come in large flocks in the early spring. They pass along about the last of April, the greater proportions only tarrying a short time; but in the fall they stay from five to eight weeks. They nest in the same places with the Redwing Blackbirds, and their nests are very much alike. In early summer they have a very pretty note, which is never heard in the fall.

Scolecophagus cyanocephalus, CabBREWER’S BLACKBIRDPsarocolius cyanocephalus, Wagler, Isis, 1829, 758. Scolecophagus cyanocephalus, Cabanis, Mus. Hein. 1851, 193.—Baird, Birds N. Am. 1858, 552.—Cass. P. A. N. S. 1866, 413.—Heerm. X, S, 53.—Cooper & Suckley, 209.—Cooper, Orn. Cal. I, 1870, 278. Scolecophagus mexicanus, Swainson, Anim. in Men. 2¼ cent. 1838, 302.—Bon. Conspectus, 1850, 423.—Newberry, Zoöl. Cal. and Or. Route; Rep. P. R. R. Surv. VI, IV, 1857, 86. Quiscalus breweri, Aud. Birds Am. VII, 1843, 345, pl. ccccxcii.

Sp. Char. Bill stout, quiscaline, the commissure scarcely sinuated; shorter than the head and the hind toe; the height nearly half length of culmen. Wing nearly an inch longer than the tail; the second quill longest; the first about equal to the third. Tail rounded and moderately graduated; the lateral feathers about .35 of an inch shorter. General color of male black, with lustrous green reflections everywhere except on the head and neck, which are glossed with purplish-violet. Female much duller, of a light brownish anteriorly; a very faint superciliary stripe. Length about 10 inches; wing, 5.30; tail, 4.40.

Hab. High Central Plains to the Pacific; south to Mexico. Pembina, Minn.; S. Illinois (Wabash Co.; R. Ridgway); Matamoras and San Antonio, Texas (breeds; Dresser, Ibis, 1869, 493); Plateau of Mexico (very abundant, and resident; Sumichrast, M. B. S. I, 553).

Autumnal specimens do not exhibit the broad rusty edges of feathers seen in S. ferrugineus.

The females and immature males differ from the adult males in much the same points as S. ferrugineus, except that the “rusty” markings are less prominent and more grayish. The differences generally between the two species are very appreciable. Thus, in S. cyanocephalus, the bill, though of the same length, is much higher and broader at the base, as well as much less linear in its upper outline; the point, too, is less decurved. The size is every way larger. The purplish gloss, which in ferrugineus is found on most of the body except the wings and tail, is here confined to the head and neck, the rest of the body being of a richly lustrous and strongly marked green, more distinct than that on the wings and tail of ferrugineus. In one specimen only, from Santa Rosalia, Mexico, is there a trace of purple on some of the wing and tail feathers.

Habits. This species was first given as a bird of our fauna by Mr. Audubon, in the supplementary pages of the seventh volume of his Birds of America. He met with it on the prairies around Fort Union, at the junction of the Yellowstone and the Missouri Rivers, and in the extensive ravines in that neighborhood, in which were found a few dwarfish trees and tall rough weeds or grasses, along the margin of scanty rivulets. In these localities he met with small groups of seven or eight of these birds. They were in loose flocks, and moved in a silent manner, permitting an approach to within some fifteen or twenty paces, and uttering a call-note as his party stood watching their movements. Perceiving it to be a species new to him, he procured several specimens. He states that they did not evince the pertness so usual to birds of this family, but seemed rather as if dissatisfied with their abode. On the ground their gait was easy and brisk. He heard nothing from them of the nature of a song, only a single cluck, not unlike that of the Redwing, between which birds and the C. ferrugineus he was disposed to place this species.

Dr. Newberry found this Blackbird common both in California and in Oregon. He saw large flocks of them at Fort Vancouver, in the last of October. They were flying from field to field, and gathered into the large spruces about the fort, in the manner of other Blackbirds when on the point of migrating.

Mr. Allen found this Blackbird, though less an inhabitant of the marshes than the Yellow-headed, associating with them in destroying the farmers’ ripening corn, and only less destructive because less numerous. It appears to be an abundant species in all the settled portions of the western region, extending to the eastward as far as Wisconsin, and even to Southeastern Illinois, one specimen having been obtained in Wisconsin by Mr. Kumlien, and others in Wabash Co., Ill., by Mr. Ridgway.

In the summer, according to Mr. Ridgway, it retires to the cedar and piñon mountains to breed, at that time seldom visiting the river valley. In the winter it resorts in large flocks to the vicinity of corrals and barn-yards, where it becomes very tame and familiar. On the 3d of June he met with the breeding-ground of a colony of these birds, in a grove of cedars on the side of a cañon, in the mountains, near Pyramid Lake. Nearly every tree contained a nest, and several had two or three. Each nest was saddled on a horizontal branch, generally in a thick tuft of foliage, and well concealed. The majority of these nests contained young, and when these were disturbed the parents flew about the heads of the intruders, uttering a soft chuck. The maximum number of eggs or young was six, the usual number four or five. In notes and manners it seemed to be an exact counterpart of the C. ferrugineus.

Dr. Suckley found these birds quite abundant at Fort Dalles, but west of the Cascade Mountains they were quite rare. At Fort Dalles it is a winter resident, where, in the cold weather, it may frequently be found in flocks in the vicinity of barn-yards and stables. Dr. Cooper also obtained specimens of this Grakle at Vancouver, and regards it as a constant resident on the Columbia River. He saw none at Puget Sound. In their notes and habits he was not able to trace any difference from the Rusty Blackbird of the Atlantic States. In winter they kept about the stables in flocks of fifties or more, and on warm days flew about among the tree-tops, in company with the Redwings, singing a harsh but pleasant chorus for hours.

Dr. Cooper states it to be an abundant species everywhere throughout California, except in the dense forests, and resident throughout the year. They frequent pastures and follow cattle in the manner of the Molothrus. They associate with the other Blackbirds, and are fond of feeding and bathing along the edges of streams. They have not much song, but the noise made by a large flock, as they sit sunning themselves in early spring, is said to be quite pleasing. In this chorus the Redwings frequently assist. At Santa Cruz he found them more familiar than elsewhere. They frequented the yards about houses and stables, building in the trees of the gardens, and collecting daily, after their hunger was satisfied, on the roofs or on neighboring trees, to sing, for an hour or two, their songs of thanks. He has seen a pair of these birds pursue and drive away a large hawk threatening some tame pigeons.

This species has an extended distribution, having been met with by Mr. Kennicott as far north as Pembina, and being also abundant as far south as Northern Mexico. In the Boundary Survey specimens were procured at Eagle Pass and at Santa Rosalia, where Lieutenant Couch found them living about the ranches and the cattle-yards.

Mr. Dresser, on his arrival at Matamoras, in July, noticed these birds in the streets of that town, in company with the Long-tailed Grakles Q. macrurus and Molothrus pecoris. He was told by the Mexicans that they breed there, but it was too late to procure their eggs. In the winter vast flocks frequented the roads near by, as well as the streets of San Antonio and Eagle Pass. They were as tame as European Sparrows. Their note, when on the wing, was a low whistle. When congregated in trees, they kept up an incessant chattering.

Dr. Coues found them permanent residents of Arizona, and exceedingly abundant. It was the typical Blackbird of Fort Whipple, though few probably breed in the immediate vicinity. Towards the end of September they become very numerous, and remain so until May, after which few are observed till the fall. They congregate in immense flocks about the corrals, and are tame and familiar. Their note, he says, is a harsh, rasping squeak, varied by a melodious, ringing whistle. I am indebted to this observing ornithologist for the following sketch of their peculiar characteristics:—

“Brewer’s Blackbird is resident in Arizona, the most abundant bird of its family, and one of the most characteristic species of the Territory. It appears about Fort Whipple in flocks in September; the numbers are augmented during the following month, and there is little or no diminution until May, when the flocks disperse to breed.