полная версия

полная версияA History of North American Birds, Land Birds. Volume 2

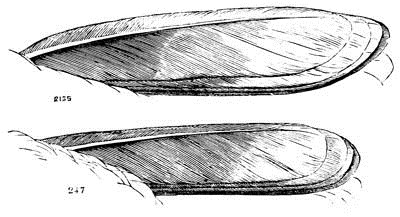

2. Wing, 2.90; tail, 3.75. Outer tail-feather with only terminal fourth of inner web white. Iris white. Hab. Florida (resident) … var. alleni.

II. P. maculatusA. Interscapulars with white streaks.

a. Outer webs of primaries not edged with white at the base.

1. Above olive-brown, the head and neck, only, continuous black; back streaked with black. White spots on wing-coverts not bordered externally with black. Wing, 3.25; tail, 4.00; hind claw, .44. Hab. Table-lands of Mexico … var. maculatus.21

2. Above black, tinged with olive on rump, and sometimes on the nape. White spots as in last. Inner web of lateral tail-feathers with terminal white spot more than one inch long; outer web broadly edged with white. Wing, 3.45; tail, 4.10; hind claw, .55. Female less deep black than male, with a general slaty-olive cast. Hab. Middle Province of United States, from Fort Tejon, California, to Upper Rio Grande, and from Fort Crook to Fort Bridger … var. megalonyx.

3. Above almost wholly black, with scarcely any olive tinge, and this only on rump. White spots restricted, and with a distinct black external border. White terminal spot on inner web of lateral tail-feather less than one inch long; outer web almost wholly black. Wing, 3.40; tail, 3.90; hind claw, .39. Female deep umber-brown, instead of black. Hab. Pacific Province of United States, south to San Francisco; West Humboldt Mountains … var. oregonus.

b. Outer webs of primaries distinctly edged with white at base.

4. Above black, except on rump, which is tinged with olivaceous. White spots very large, without black border. Inner web of lateral tail-feather with terminal half white, the outer web almost wholly white. Wing, 3.50; tail, 3.90; hind claw, .39. Female umber-brown, replacing black. Hab. Plains between Rocky Mountains and the Missouri; Saskatchewan Basin … var. arcticus.

B. Interscapulars without white streaks.

5. Above dusky olive; white spots on scapulars and wing-coverts small, and without black edge. Tail-patches very restricted (outer only .40 long). No white on primaries. Wing, 2.85; tail, 3.10. Female scarcely different. Hab. Socorro Island, off west coast of Mexico … var. carmani.22

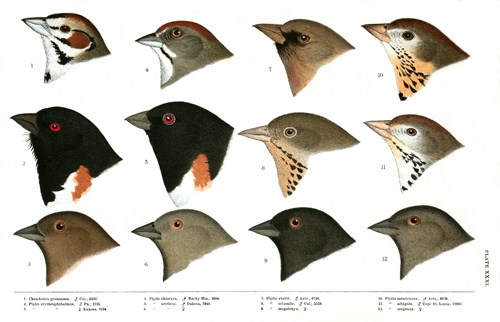

PLATE XXXI.

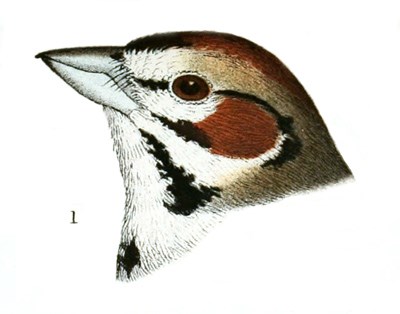

1. Chondestes grammaca. ♂ Cal., 6300.

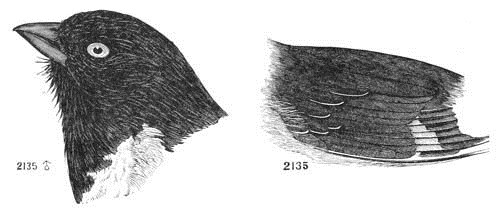

2. Pipilo erythrophthalmus. ♂ Pa., 2135.

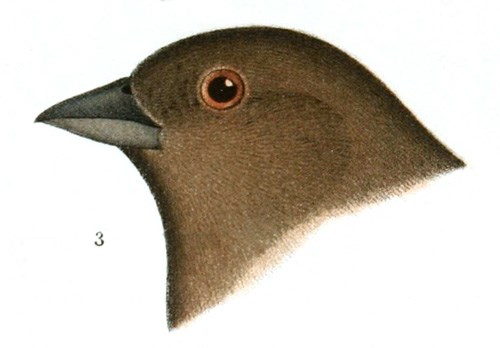

3. Pipilo erythrophthalmus. ♀ Kansas, 8194.

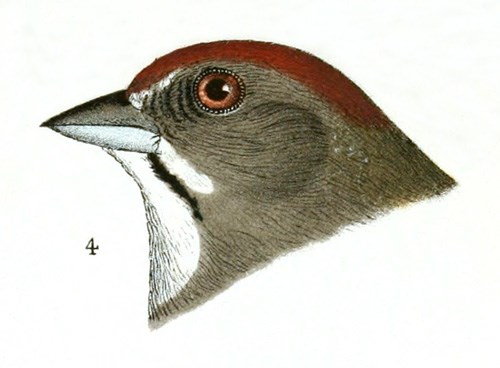

4. Pipilo chlorura. ♂ Rocky Mts., 2644.

5. Pipilo arcticus. ♂ Dakota, 1944.

6. Pipilo arcticus. ♀.

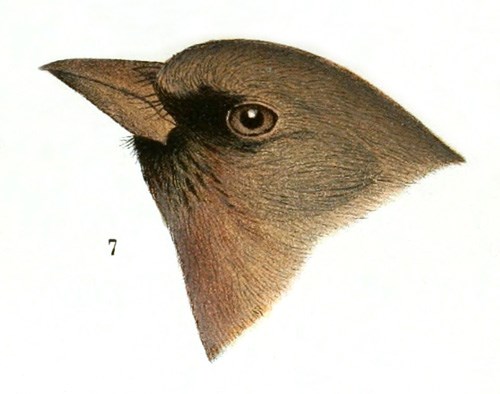

7. Pipilo aberti. ♂ Ariz., 6748.

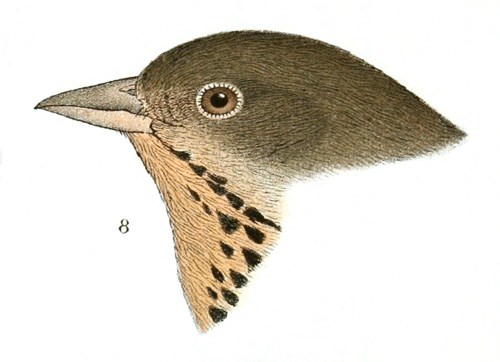

8. Pipilo crissalis. ♂ Cal., 5559.

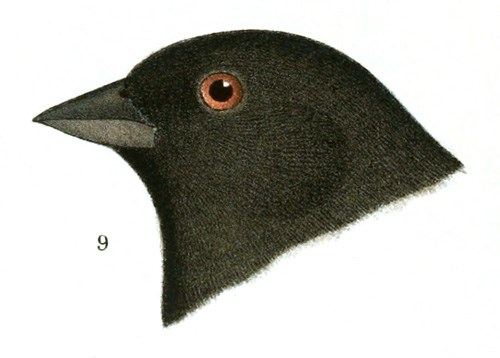

9. Pipilo megalonyx. ♀.

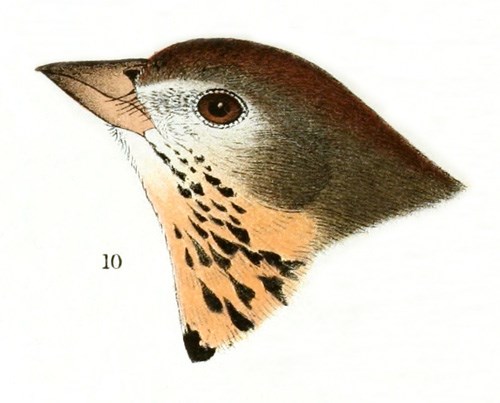

10. Pipilo mesoleucus. ♂ Ariz., 6829.

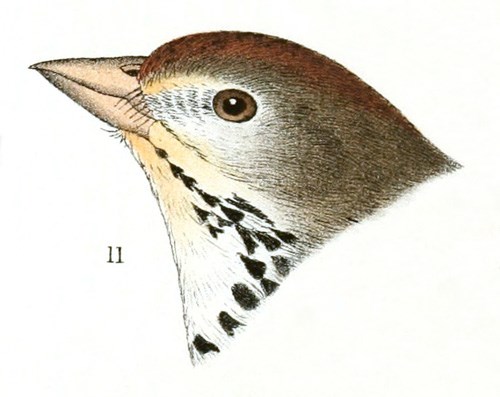

11. Pipilo albigula. ♂ Cape St. Lucas, 12993.

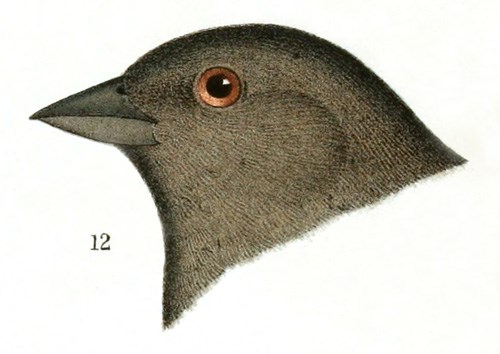

12. Pipilo oregonus. ♀.

Pipilo erythrophthalmus, VieillotGROUND ROBIN; TOWHEE; CHEWINK

Fringilla erythrophthalma, Linn. Syst. Nat. I, 1766, 318.—Aud. Orn. Biog. I, 1832, 151; V, 511, pl. xxix. Emberiza erythrophthalma, Gm. Syst. Nat. I, 1788, 874.—Wilson, Am. Orn. VI, 1812, 90, pl. liii. Pipilo erythrophthalmus, Vieill. Gal. Ois. I, 1824, 109, pl. lxxx.—Bon. List, 1838.—Ib. Conspectus, 1850, 487.—Aud. Syn. 1839, 124.—Ib. Birds Am. III, 1841, 167, pl. cxcv.—Baird, Birds N. Am. 1858, 512.—Samuels, 333. Pipilo ater, Vieill. Nouv. Dict. XXXIV, 1819, 292. Towhee Bird, Catesby, Car. I, 34. Towhee Bunting, Latham, Syn. II, I, 1783, 199.—Pennant, II, 1785, 359.

2135 ♂

Sp. Char. Upper parts generally, head and neck all round, and upper part of the breast, glossy black, abruptly defined against the pure white which extends to the anus, but is bounded on the sides and under the wings by light chestnut, which is sometimes streaked externally with black. Feathers of throat white in the middle. Under coverts similar to sides, but paler. Edges of outer six primaries with white at the base and on the middle of the outer web; inner two tertiaries also edged externally with white. Tail-feathers black; outer web of the first, with the ends of the first to the third, white, decreasing from the exterior one. Outermost quill usually shorter than ninth, or even than secondaries; fourth quill longest, fifth scarcely shorter. Iris red; said to be sometimes paler, or even white, in winter. Length, 8.75; wing, 3.75; tail, 4.10. Bill black, legs flesh-color. Female with the black replaced by a rather rufous brown.

Hab. Eastern United States to the Missouri River; Florida (in winter).

The tail-feathers are only moderately graduated on the sides; the outer about .40 of an inch shorter than the middle. The outer tail-feather has the terminal half white, the outline transverse; the white of the second is about half as long as that of the first; of the third half that of the second. The chestnut of the sides reaches forward to the black of the neck, and is visible when the wings are closed.

A young bird has the prevailing color reddish-olive above, spotted with lighter; beneath brownish-white, streaked thickly with brown.

The description above given may be taken as representing the average of the species in the Northern and Middle States. Most specimens from the Mississippi Valley differ in having the two white patches on the primaries confluent; but this feature is not sufficiently constant to make it worthy of more than passing notice, for occasionally western specimens have the white spaces separated, as in the majority of eastern examples, while among the latter there may, now and then, be found individuals scarcely distinguishable from the average of western ones.

Pipilo erythrophthalmus.

2135 ♂

In Florida, however, there is a local, resident race, quite different from these two northern styles, which are themselves not enough unlike to be considered separately. This Florida race differs in much smaller size, very restricted white on both wing and tail, and in having a yellowish-white instead of blood-red iris. Further remarks on this Florida race will be found under its proper heading (p. 708), as P. erythrophthalmus, var. alleni.

Specimens of erythrophthalmus, as restricted, from Louisiana, as is the case with most birds from the Lower Mississippi region, exhibit very intense colors compared with those from more northern portions, or even Atlantic coast specimens from the same latitude.

Habits. The Ground Robin, Towhee, Chewink, Charee, or Joreet, as it is variously called, has an extended distribution throughout the eastern United States, from Florida and Georgia on the southeast to the Selkirk Settlements on the northwest, and as far to the west as the edge of the Great Plains, where it is replaced by other closely allied races. It breeds almost wherever found, certainly in Georgia, and, I have no doubt, sparingly in Florida.

This bird was not observed in Texas by Mr. Dresser. It has been found in Western Maine, where it is given by Mr. Verrill as a summer visitant, and where it breeds, but is not common. It arrives there the first of May. It is not given by Mr. Boardman as occurring in Eastern Maine. In Massachusetts it is a very abundant summer visitant, arriving about the last of April, and leaving about the middle of October. It nests there the last of May, and begins to sit upon the eggs about the first of June. It is slightly gregarious just as it is preparing to leave, but at all other times is to be met with only in solitary pairs.

The Ground Robin is in many respects one of the most strongly characterized of our North American birds, exhibiting peculiarities in which all the members of this genus share to a very large degree. They frequent close and sheltered thickets, where they spend a large proportion of their time on the ground among the fallen leaves, scratching and searching for worms, larvæ, and insects. Though generally resident in retired localities, it is far from being a shy or timid bird. I have known it to show itself in a front yard, immediately under the windows of a dwelling and near the main street of the village, where for hours I witnessed its diligent labors in search of food. The spot was very shady, and unfrequented during the greater part of the day. It was not disturbed when the members of the family passed in or out.

The call-note of this bird is very peculiar, and is variously interpreted in different localities. It has always appeared to me that the Georgian jo-rēēt was at least as near to its real notes as tow-hēē. Its song consists of a few simple notes, which very few realize are those of this bird. In singing, the male is usually to be seen on the top of some low tree. These notes are uttered in a loud voice, and are not unmusical. Wilson says its song resembles that of the Yellow-Hammer of Europe, but is more varied and mellow. Nuttall speaks of its notes as simple, guttural, and monotonous, and of its voice as clear and sonorous. The song, which he speaks of as quaint and somewhat pensive, he describes as sounding like t’sh’d-wĭtee-tĕ-tĕ-tĕ-tĕ-tĕ.

Wilson says this bird is known in Pennsylvania as the “Swamp Robin.” If so, this is a misnomer. In New England it has no predilection for low or moist ground; and I have never found it in such situations. Its favorite haunts are dry uplands, near the edges of woods, or high tracts covered with a low brushwood, selecting for nesting-places the outer skirts of a wood, especially one of a southern aspect. The nest is sunk in a depression in the ground, the upper edges being usually just level with the ground. It is largely composed of dry leaves and coarse stems as a base, within which is built a firmer nest of dry bents well arranged, usually with no other lining. It is generally partially concealed by leaves or a tuft of grass, and is not easily discovered unless the female is seen about it.

Dr. Coues says these Buntings are chiefly spring and autumnal visitants near Washington, only a few breeding. They are very abundant from April 25 to May 10, and from the first to the third week of October, and are partially gregarious. Their migrations are made by day, and are usually in small companies in the fall, but singly in the spring. Wilson found them in the middle districts of Virginia, and from thence south to Florida, during the months of January, February, and March. Their usual food is obtained among the dry leaves, though they also feed on hard seeds and gravel. They are not known to commit any depredations upon harvests. They may be easily accustomed to confinement, and in a few days will become quite tame. When slightly wounded and captured, they at first make a sturdy resistance, and bite quite severely. They are much attached to their young, and when approached evince great anxiety, the female thrusting herself forward to divert attention by her outcries and her simulated lameness.

The eggs of this species are of a rounded-oval shape, and have a dull-white ground, spotted with dots and blotches of a wine-colored brown. These usually are larger than in the other species, and are mostly congregated about the larger end, and measure .98 of an inch in length by .80 in breadth.

Pipilo erythrophthalmus, var. alleni, CouesWHITE-EYED CHEWINK; FLORIDA CHEWINKPipilo alleni, Coues, American Naturalist, V, Aug. 1871, 366.

Sp. Char. Similar to erythrophthalmus, but differing in the following respects: White spaces on wings and tail much restricted, those on inner webs of lateral tail-feathers only .50 to .75 long. Size very much smaller, except the bill, which is absolutely larger. Iris white.

♂. (55,267, Dummits’s Grove, Florida, March, 1869.) Length, 7.75; wing, 3.00; tail, 3.75; bill from nostril, .38; tarsus, .97.

♀. (55,271, same locality and date.) Wing, 3.00; tail, 3.50; bill from nostril, .37; tarsus, .91. White on primaries almost absent.

Pipilo erythrophthalmus.

2135, 247,

var. alleni.

This interesting variety of Pipilo erythrophthalmus was found in Florida, in the spring of 1869, by Mr. C. J. Maynard, and probably represents the species as resident in that State. It is considerably smaller than the average (length, 7.75; extent, 10.00; wing, 3.00; tarsus, .95), and has very appreciably less white on the tail. The outer web of outer feather is only narrowly edged with white, instead of being entirely so to the shaft (except in one specimen), and the terminal white tip, confined to the inner web, is only from .50 to .75 of an inch long, instead of 1.25 to 1.75, or about the amount on the second feather of northern specimens, as shown in the accompanying figures. There is apparently a greater tendency to dusky streaks and specks in the rufous of the side of the breast or in the adjacent white. Resident specimens from Georgia are intermediate in size and color between the northern and Florida races.

The bill of Mr. Maynard’s specimen is about the size of that of more northern ones; the iris is described by him as pale yellowish-white, much lighter than usual.

Pipilo maculatus,23 var. megalonyx, BairdLONG-CLAWED TOWHEE BUNTINGPipilo megalonyx, Baird, Birds N. Am. 1858, 515, pl. lxxiii.—Heerm. X, S, 51 (nest).—Cooper, Orn. Cal. I, 242.

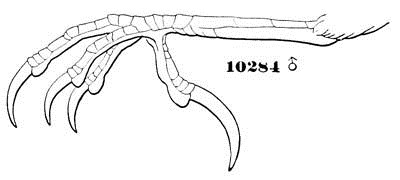

10284 ♂

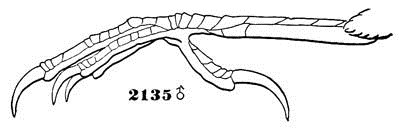

Sp. Char. Similar to P. arcticus in amount of white on the wings and scapulars, though this frequently edged with black, but without basal white on outer web of primaries. Outer edge of outer web of external tail-feather white, sometimes confluent with that at tip of tail. Concealed white spots on feathers of side of neck. Claws enormously large, the hinder longer than its digit; the hind toe and claw reaching to the middle of the middle claw, which, with its toe, is as long as or longer than the tarsus. Inner lateral claw reaching nearly to the middle of middle claw. Length, 7.60; wing, 3.25; hind toe and claw, .90. Female with the deep black replaced by dusky slaty-olive.

Hab. Southern coast of California and across through valleys of Gila and Rio Grande; north through the Great Basin across from Fort Crook, California, to Fort Bridger, Wyoming.

This form constitutes so strongly marked a variety as to be worthy of particular description. The general appearance is that of P. arcticus, which it resembles in the amount of white spotting on the wings. This, however, does not usually involve the whole outer web at the end, but, as in oregonus, has a narrow border of black continued around the white terminally and sometimes externally. There is not quite so much of a terminal white blotch on the outer tail-feather, this being but little over an inch in length, and the outer web of the same feather is never entirely white, though always with an external white border, which sometimes is confluent with the terminal spot, but usually leaves a brown streak near the end never seen in arcticus, which also has the whole outer web white except at the base. From oregonus the species differs in the much greater amount of white on the wings and the less rounded character of the spots. Oregonus, too, has the whole outer web of external tail-feather black, and the terminal white spot of the inner web less than an inch in length. We have never seen in oregonus any concealed white spotting on the sides of the head.

The greatest difference between this race and the two others lies in the stout tarsi and enormously large claws, as described, both the lateral extending greatly beyond the base of the middle one, the hinder toe and claw nearly as long as the tarsus. The only North American passerine birds having any approach to this length of claw are those of the genus Passerella.

This great development of the claws is especially apparent in specimens from the Southern Sierra Nevada, the maximum being attained in the Fort Tejon examples; those from as far north as Carson City, Nev., however, are scarcely smaller. In most Rocky Mountain Pipilos, the claws are but little longer than in arcticus.

In this race the female is not noticeably different from the male, being of a merely less intense black,—not brown,—and conspicuously different as in arcticus and oregonus; there is, however, some variation among individuals in this respect, but none are ever so light as the average in the other races.

The young bird is dusky-brown above, with a slight rusty tinge, and obsolete streaks of blackish. White markings as in adult, but tinged with rusty. Throat and breast rusty-white, broadly streaked with dusky; sides only tinged with rufous.

Habits. According to Mr. Ridgway’s observations, the P. megalonyx replaces in the Rocky Mountain region and in the greater portion of the Great Basin the P. arcticus of the Plains, from their eastern slope eastward to the Missouri River, and the P. oregonus of the Northern Sierra Nevada and Pacific coast. It is most nearly related to the latter. He became familiar with the habits of this species near Salt Lake City, having already made like observations of the oregonus at Carson. A short acquaintance with the former, after a long familiarity with the latter, enabled him to note a decided difference in the notes of the two birds, yet in their external appearance they were hardly distinguishable, and he was at first surprised to find the same bird apparently uttering entirely different notes, the call-note of P. megalonyx being very similar to that of the common Catbird. The song of this species, he adds, has considerable resemblance in style to that of the eastern P. erythrophthalmus, and though lacking its musical character, is yet far superior to that of P. oregonus. This bird is also much less shy than the western one, and is, in fact, quite as unsuspicious as the eastern bird.

Nests, with eggs, were found on the ground, among the scrub-oaks of the hillsides, from about the 20th of May until the middle of June.

This species has been obtained on the southern coast of California, and through to the valleys of the Gila and the Rio Grande. In California it was obtained near San Francisco by Mr. Cutts and Mr. Hepburn; at Santa Clara by Dr. Cooper; at Monterey by Dr. Canfield; in the Sacramento Valley by Dr. Heermann; at San Diego by Dr. Hammond; at Fort Tejon by Mr. Xantus; at Saltillo, Mexico, by Lieutenant Couch; in New Mexico by Captain Pope; and at Fort Thorn by Dr. Henry.

Lieutenant Couch describes it as a shy, quiet bird, and as found in woody places.

Dr. Kennerly met with this bird at Pueblo Creek, New Mexico, January 22, 1854. It first attracted his attention early in the month of January, in the Aztec Mountains, along Pueblo Creek. There it was often met with, but generally singly. It inhabited the thickest bushes, and its motions were so constant and rapid, as it hopped from twig to twig, that they found it difficult to procure specimens. Its flight was rapid, and near the ground.

Dr. Cooper speaks of this species as a common and resident bird in all the lower districts of California, and to quite a considerable distance among the mountains. It was also found on the islands of Catalina and San Clemente, distant sixteen miles from the mainland. Though found in New Mexico, Dr. Cooper has met with none in the barren districts between the Coast Range and the Colorado, nor in the valley of the latter.

Their favorite residence is said to be in thickets and in oak groves, where they live mostly on the ground, scratching among the dead leaves in the concealment of the underbrush, and very rarely venturing far from such shelter. They never fly more than a few yards at a time, and only a few feet above the ground. In villages, where they are not molested, they soon become more familiar, take up their abodes in gardens, and build their nests in the vicinity of houses.

Dr. Cooper gives them credit for little musical power. Their song is said to be only a feeble monotonous trill, from the top of some low bush. When alarmed, they have a note something like the mew of a cat. On this account they are popularly known as Catbirds. He adds that the nest is made on the ground, under a thicket, and that it is constructed of dry leaves, stalks, and grass, mingled with fine roots. The eggs, four or five in number, are greenish-white, minutely speckled with reddish-brown, and measure one inch by .70.

Dr. Coues found this species a very abundant and resident species in Arizona. It was rather more numerous in the spring and in the fall than at other times. He found it shy and retiring, and inhabiting the thickest brush. Its call-note is said to be almost exactly like that of our eastern Catbird. He describes its song as a rather harsh and monotonous repetition of four or six syllables, something like that of the Euspiza americana. He found females with mature eggs in their ovaries as early as May 5.

A nest of this species, collected by Mr. Ridgway near Salt Lake City, May 26, was built on the ground, among scrub-oak brush. It is a very slight structure, composed almost entirely of coarse dry stems of grass, with a few bits of coarse inner bark, and with a base made up wholly with the latter material, and having a diameter of about four inches.

The eggs of this nest, four in number, have an average measurement of .95 of an inch in length by .73 in breadth. Their ground-color is crystalline-white, covered very generally with spots and small blotches of purplish and wine-colored brown, somewhat aggregated at the larger end.

Pipilo maculatus, var. oregonus, BellOREGON GROUND ROBINPipilo oregonus, Bell, Ann. N. Y. Lyc. V, 1852, 6 (Oregon).—Bonap. Comptes Rendus, XXXVII, Dec. 1853, 922.—Ib. Notes Orn. Delattre, 1854, 22 (same as prec.).—Baird, Birds N. Am. 1858, 513.—Lord, Pr. R. A. Inst. IV, 64, 120 (British Col.).—Cooper & Suckley, 200.—Cooper, Orn. Cal. I, 241. Fringilla arctica, Aud. Orn. Biog. V, 1839, 49, pl. cccxciv. (not of Swainson). Pipilo arctica, Aud. Syn. 1839, 123.—Ib. Birds Am. III, 1841, 164, pl. cxciv.

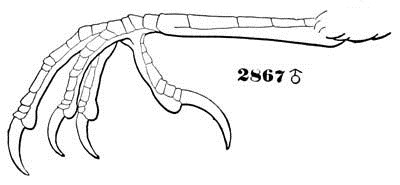

2867 ♂

Sp. Char. Upper surface generally, with the head and neck all round to the upper part of the breast, deep black; the rest of lower parts pure white, except the sides of the body and under tail-coverts, which are light chestnut-brown; the latter rather paler. The outer webs of scapulars (usually edged narrowly with black) and of the superincumbent feathers of the back, with a rounded white spot at the end of the outer webs of the greater and middle coverts; the outer edges of the innermost tertials white; no white at the base of the primaries. Outer web of the first tail-feather black, occasionally white on the extreme edge; the outer three with a white tip to the inner web. Outer quill shorter than ninth, or scarcely equalling the secondaries; fourth quill longest; fifth scarcely shorter. Length, 8.25; wing, 4.40; tail, 4.00. Female with the black replaced by a more brownish tinge. Claws much as in erythrophthalmus.