полная версия

полная версияA History of North American Birds, Land Birds. Volume 2

Of this genus, only two species are known, one of them being exclusively South American, the other belonging to North America, but in different regions modified into representative races. They may be defined as follows.

Species and VarietiesCommon Characters. Male. Bright vermilion-red, more dusky purplish on upper surface; feathers adjoining base of bill black for greater or less extent. Female. Above olivaceous, the wings, tail, and crest reddish; beneath olivaceous-whitish, slightly tinged on jugulum with red.

C. virginianus. Culmen nearly straight; commissure with a slight lobe; upper mandible as deep as the lower, perfectly smooth. Bill red. Black patch covering whole throat, its posterior outline convex. Female. Lining of wing deep vermilion. Olivaceous-gray above, the wings and tail strongly tinged with red; crest only dull red, without darker shaft-streaks. Beneath wholly light ochraceous. No black around bill.

A. Crest-feathers soft, blended. Rump not lighter red than back.

a. Black of the lores passing broadly across forehead. Crest brownish-red. Bill moderate.

Culmen, .75; gonys, .41; depth of bill, .54. Feathers of dorsal region broadly margined with grayish. Wing, 4.05; tail, 4.50; crest, 1.80. Hab. Eastern Province of United States, south of 40°. Bermudas … var. virginianus.

b. Black of the lores not meeting across forehead; crest pure vermilion. Bill robust.

Culmen, .84; gonys, .47; depth of bill, .70. Feathers of dorsal region without grayish borders; red beneath more intense; wing, 3.60; tail, 4.20; crest, 2.00. Hab. Eastern Mexico (Mirador; Yucatan; “Honduras”) … var. coccineus.15

Culmen, .82; gonys, .47; depth of bill, .65. Feathers of dorsal region with distinct gray borders; red beneath lighter. Wing, 4.00; tail, 5.00; crest, 2.00. Hab. Cape St. Lucas, and Arizona; Tres Marias Islands. (Perhaps all of Western Mexico, north of the Rio Grande de Santiago.) … var. igneus.

B. Crest-feathers stiff, compact. Rump decidedly lighter red than the back.

Culmen, .75; gonys, .41; depth of bill, .57. Dorsal feathers without grayish margins; red as in the last. Wing, 3.40; tail, 3.80; crest, 2.00. Hab. Western Mexico; Colima. “Acapulco et Realejo.” … var. carneus.16

C. phœniceus. 17 Culmen much arched; commissure arched; upper mandible not as deep as lower, and with grooves forward from the nostril, parallel with the curve of the culmen. Bill whitish-brown. Black patch restricted to the chin, its posterior outline deeply concave.

Crest-feathers stiff and compact. No black above, or on lores; crest pure vermilion; rump light vermilion, much lighter than the back, which is without gray edges to feathers. Culmen, .75; gonys, .39; height of bill, .67; wing, 3.50; tail, 3.90; crest, 2.20. Female. Lining of wing buff; above ashy-olivaceous, becoming pure ash on head and neck, except their under side. Crest-feathers vermilion with black shafts; no red tinge on wings, and only a slight tinge of it on tail. Forepart of cheeks and middle of throat white; rest of lower part deep ochraceous. Black around bill as in the male. Hab. Northern South America; Venezuela; New Granada.

Cardinalis virginianus, BonapREDBIRD; CARDINAL GROSBEAKCoccothraustes virginiana, Brisson, Orn. III, 1760, 253. Loxia cardinalis, Linn. Syst. I, 1766, 300.—Wilson, Am. Orn. II, 1810, 38, pl. vi, f. 1, 2. Coccothraustes cardinalis, Vieill. Dict. Fringilla (Coccothraustes) cardinalis, Bon. Obs. Wils. 1825, No. 79. Fringilla cardinalis, Nutt. Man. I, 1832, 519.—Aud. Orn. Biog. II, 1834, 336; V, 514, pl. clix. Pitylus cardinalis, Aud. Syn. 1839, 131.—Ib. Birds Am. III, 1841, 198, pl. cciii. Cardinalis virginianus, Bon. List, 1838.—Ib. Consp. 1850, 501.—Baird, Birds N. Am. 1858, 509.—Max. Cab. J. VI, 1858, 268. Grosbec de Virginie, Buff. Pl. enl. 37.

Cardinalis virginianus.

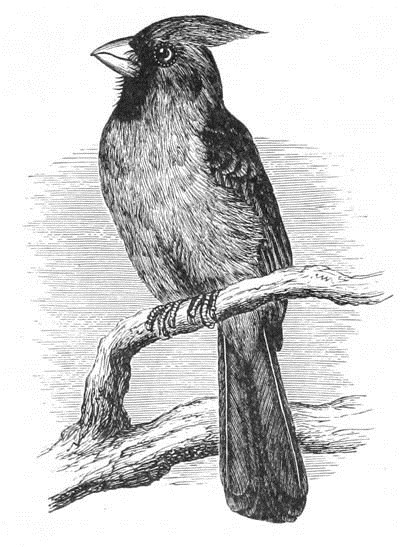

Sp. Char. A flattened crest of feathers on the crown. Bill red. Body generally bright vermilion-red, darker on the back, rump, and tail. The feathers of the back and rump bordered with brownish-gray. Narrow band around the base of the bill, extending to eyes, with chin and upper part of the throat black.

Female of a duller red, and this only on the wings, tail, and elongated feathers of the crown. Above light olive; tinged with yellowish on the head; beneath brownish-yellow, darkest on the sides and across the breast. Black about the head only faintly indicated. Length, 8.50; wing, 4.00; tail, 4.50; culmen, .75; depth of bill, .58; breadth of upper mandible, .35. (28,286 ♂, Mount Carmel, Southern Illinois.)

Hab. More southern portions of United States to the Missouri. Probably along valley of Rio Grande to Rocky Mountains.

The bill of this species is very large, and shaped much as in Hedymeles ludovicianus. The central feathers of the crest of the crown are longer than the lateral; they spring from about the middle of the crown, and extend back about an inch and a half from the base of the bill. The wings are much rounded, the fourth longest, the second equal to the seventh, the first as long as the secondaries. The tail is long, truncate at the end, but graduated on the sides; the feathers are broad to the end, truncated obliquely at the end.

Most North American specimens we have seen have the feathers of the back edged with ashy; the more northern the less brightly colored, and larger. Mexican skins (var. coccineus) are deeper colored and without the olivaceous. In all specimens from eastern North America the frontal black is very distinct.

Specimens from the Eastern Province of United States, including Florida and the Bermudas, are all alike in possessing those features distinguishing the restricted var. virginianus from the races of Mexico, namely, the wide black frontal band, and distinct gray edges to dorsal feathers, with small bill. Specimens from Florida are scarcely smaller, and are not more deeply colored than some examples from Southern Illinois. Rio Grande skins, however, are slightly less in size, though identical in other respects.

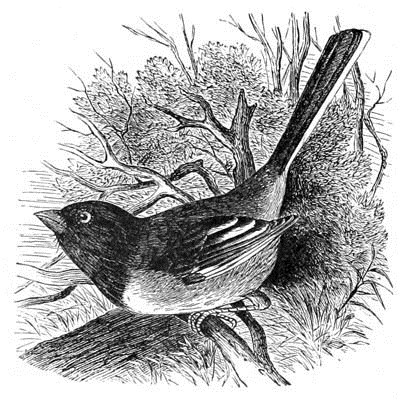

Habits. The Cardinal Grosbeak, the Redbird of the Southern States, is one of our few birds that present the double attraction of a brilliant and showy plumage with more than usual powers of song. In New England and the more northern States it is chiefly known by its reputation as a cage-bird, both its bright plumage and its sweet song giving it a high value. It is a very rare and only an accidental visitor of Massachusetts, though a pair was once known to spend the summer and to rear its brood in the Botanical Gardens of Harvard College in Cambridge. It is by no means a common bird even in Pennsylvania. In all the Southern States, from Virginia to Mexico, it is a well-known favorite, frequenting gardens and plantations, and even breeding within the limits of the larger towns and cities. A single specimen of this bird was obtained near Dueñas, Guatemala, by Mr. Salvin.

The song of this Grosbeak is diversified, pleasant, and mellow, delivered with energy and ease, and renewed incessantly until its frequent repetitions somewhat diminish its charms. Its peculiar whistle is not only loud and clear, resembling the finest notes of the flageolet, but is so sweet and so varied that by some writers it has been considered equal even to the notes of the far-famed Nightingale of Europe. It is, however, very far from being among our best singers; yet, as it is known to remain in full song more than two thirds of the year, and while thus musical to be constant and liberal in the utterance of its sweet notes, it is entitled to a conspicuous place among our singing birds.

In its cage life the Cardinal soon becomes contented and tame, and will live many years in confinement. Wilson mentions one instance in which a Redbird was kept twenty-one years. They sing nearly throughout the year, or from January to October. In the extreme Southern States they are more or less resident, and some may be found all the year round. There is another remarkable peculiarity in this species, and one very rarely to be met with among birds, which is that the female Cardinal Grosbeak is an excellent singer, and her notes are very nearly as sweet and as good as those of her mate.

This species has been traced as far to the west in its distribution as the base of the Rocky Mountains, and into Mexico at the southwest. In Mexico it is also replaced by a very closely allied variety, and at Cape St. Lucas by still another. It is given by Mr. Lawrence among the birds occurring near New York City. He has occasionally met with it in New Jersey and at Staten Island, and, in one instance, on New York Island, when his attention was attracted to it by the loudness of its song.

It is given by Mr. Dresser as common throughout the whole of Texas during the summer, and almost throughout the year, excepting only where the P. sinuata is found. At Matamoras it was very common, and may be seen caged in almost every Mexican hut. He found it breeding in great abundance about San Antonio in April and May.

Mr. Cassin states that the Cardinal Bird is also known by the name of Virginia Nightingale. He adds that it inhabits, for the greater part, low and damp woods in which there is a profuse undergrowth of bushes, and is particularly partial to the vicinity of watercourses. The male bird is rather shy and careful of exposing himself.

Wilson mentions that in the lower parts of the Southern States, in the neighborhood of settlements, he found them more numerous than elsewhere. Their clear and lively notes, even in the months of January and February, were, at that season, almost the only music. Along the roadsides and fences he found them hovering in small groups, associated with Snowbirds and various kinds of Sparrows. Even in Pennsylvania they frequent the borders of creeks and rivulets during the whole year, in sheltered hollows, covered with holly, laurel, and other evergreens. They are very fond of Indian corn, a grain that is their favorite food. They are also said to feed on various kinds of fruit.

The males of this species, during the breeding season, are described as very pugnacious, and when confined together in the same cage they fight violently. The male bird has even been known to destroy its mate. In Florida Mr. Audubon found these birds mated by the 8th of February. The nest is built in bushes, among briers, or in low trees, and in various situations, the middle of a field, near a fence, or in the interior of a thicket, and usually not far from running water. It has even been placed in the garden close to the planter’s house. It is loosely built of dry leaves and twigs, with a large proportion of dry grasses and strips of the bark of grapevines. Within, it is finished and lined with finer stems of grasses wrought into a circular form. There are usually two, and in the more Southern States three, broods in a season.

Mr. Audubon adds that they are easily raised from the nest, and have been known to breed in confinement.

The eggs of this species are of an oblong-oval shape, with but little difference at either end. Their ground-color appears to be white, but is generally so thickly marked with spots of ashy-brown and faint lavender tints as to permit but little of its ground to be seen. The eggs vary greatly in size, ranging from 1.10 inches to .98 of an inch in length, and from .80 to .78 in breadth.

Cardinalis virginianus, var. igneus, BairdCAPE CARDINALCardinalis igneus, Baird, Pr. Ac. Sc. Phila. 1859, 305 (Cape St. Lucas).—Elliot, Illust. N. Am. Birds, I, xvi.—Cooper, Orn. Cal. 1, 238. Cardinalis virginianus, Finsch, Abh. Nat. Brem. 1870, 339.

Sp. Char. Resembling virginianus, having, like it, the distinct grayish edges to feathers of the dorsal region. Red lighter, however, and the top of head, including crest, nearly pure vermilion, instead of brownish-red. Black of the lores not passing across the forehead, reaching only to the nostril. Wing, 4.00; tail, 5.00; culmen, .83; depth of bill, .66; breadth of upper mandible, .38. (No. 49,757 ♂, Camp Grant, 60 miles east of Tucson, Arizona).

Female distinguishable from that of virginianus only by more swollen bill, and more restricted dusky around base of bill. Young: bill deep black.

Hab. Cape St. Lucas; Camp Grant, Arizona; Tres Marias Islands (off coast of Mexico, latitude between 21° and 22° north). Probably Western Mexico, from Sonora south to latitude of about 20°.

In the features pointed out above, all specimens from Arizona and Tres Marias, and of an exceedingly large series collected at Cape St. Lucas, differ from those of other regions.

No specimens are in the collection from Western Mexico as far south as Colima, but birds from this region will, without doubt, be found referrible to the present race.

Habits. There appears to be nothing in the habits of this form of Cardinal, as far as known, to distinguish it from the Virginia bird; the nest and eggs, too, being almost identical. The latter average about one inch in length, and .80 in breadth. Their ground-color is white, with a bluish tint. Their markings are larger, and more of a rusty than an ashy brown, and the purple spots are fewer and less marked than in C. virginianus.

The memoranda of Mr. John Xantus show that in one instance a nest of this bird, containing two eggs, was found in a mimosa bush four feet from the ground; another nest, with one egg, in a like situation; a third, containing three eggs, was about three feet from the ground; a fourth, with two eggs, was also found in a mimosa, but only a few inches above the ground.

Genus PIPILO, VieillotPipilo, Vieillot, Analyse, 1816 (Agassiz). (Type, Fringilla erythrophthalma, Linn.)

Pipilo fuscus.

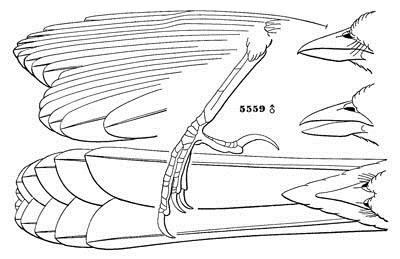

5559 ♂

Gen. Char. Bill rather stout; the culmen gently curved, the gonys nearly straight; the commissure gently concave, with a decided notch near the end; the lower jaw not so deep as the upper; not as wide as the gonys is long, but wider than the base of the upper mandible. Feet large, the tarsus as long as or a little longer than the middle toe; the outer lateral toe a little the longer, and reaching a little beyond the base of the middle claw. The hind claw about equal to its toe; the two together about equal to the outer toe. Claws all stout, compressed, and moderately curved; in some western specimens the claws much larger. Wings reaching about to the end of the upper tail-coverts; short and rounded, though the primaries are considerably longer than the nearly equal secondaries and tertials; the outer four quills are graduated, the first considerably shorter than the second, and about as long as the secondaries. Tail considerably longer than the wings, moderately graduated externally; the feathers rather broad, most rounded off on the inner webs at the end.

Pipilo erythrophthalmus.

The colors vary; the upper parts are generally uniform black or brown, sometimes olive; the under white or brown; no central streaks on the feathers. The hood sometimes differently colored.

In the large number of species or races included in this genus by authors, there are certain differences of form, such as varying graduation of tail, length of claw, etc., but scarcely sufficient to warrant its further subdivision. In coloration, however, we find several different styles, which furnish a convenient method of arrangement into groups.

Few genera in birds exhibit such constancy in trifling variations of form and color, and as these are closely connected with geographical distribution, it seems reasonable to reduce many of the so-called species to a lower rank. In the following synopsis, we arrange the whole of North American and Mexican Pipilos into four sections, with their more positive species, and in the subsequent discussion of the sections separately we shall give what appear to be the varieties.

SpeciesA. Sides and lower tail-coverts rufous, in sharp contrast with the clear white of the abdomen. Tail-feathers with whitish patch on end of inner webs.

a. Head and neck black, sharply defined against the white of breast. Rump olive or blackish.

Black or dusky olive above1. P. maculatus. White spots on tips of both rows of wing-coverts, and on scapulars. No white patch on base of primaries. Hab. Mexico, and United States west of the Missouri. (Five races.)

2. P. erythrophthalmus. No white spots on wing-coverts, nor on scapulars. A white patch on base of primaries. Hab. Eastern Province of United States. (Two races.)

Bright olive-green above3. P. macronyx.18 Scapulars and wing-coverts (both rows) with distinct greenish-white spots on tips of outer webs.

4. P. chlorosoma.19 Scapulars and wing-coverts without trace of white spots. Hab. Table-lands of Mexico. (Perhaps these are two races of one species, macronyx.)

b. Head and neck ashy, paler on jugulum, where the color fades gradually into the white of breast. Rump and upper tail-coverts bright rufous.

5. P. superciliosa.20 An obsolete whitish superciliary stripe. Greater wing-coverts obsoletely whitish at tips; no other white markings on upper parts, and the tail-patches indistinct. Hab. Brazil. (Perhaps not genuine Pipilo.)

B. Sides ashy or tinged with ochraceous; lower tail-coverts ochraceous, not sharply contrasted with white on the abdomen, or else the abdomen concolor with the side. Head never black, and upper parts without light markings (except the wing in fuscus var. albicollis).

a. Wings and tail olive-green.

6. P. chlorurus. Whole pileum (except in young) deep rufous, sharply defined. Whole throat pure white, immaculate, and sharply defined against the surrounding deep ash; a maxillary and a short supraloral stripe of white. Anterior parts of body streaked in young. Hab. Western Province of United States.

b. Wings and tail grayish-brown.

7. P. fuscus. A whitish or ochraceous patch covering the throat contrasting with the adjacent portions, and bounded by dusky specks. Lores and chin like the throat. Hab. Mexico, and United States west of Rocky Mountains. (Five races.)

8. P. aberti. Throat concolor with the adjacent portions, and without distinct spots. Lores and chin blackish. Hab. Colorado region of Middle Province, United States. (Only one form known.)

SECTION IHead blackPipilo erythrophthalmusAfter a careful study of the very large collection of Black-headed Pipilos (leaving for the present the consideration of those with olive-green bodies) in the Smithsonian Museum, we have come finally to the conclusion that all the species described as having the scapulars and wing-coverts spotted with white—as arcticus, oregonus, and megalonyx, and even including the differently colored P. maculatus of Mexico—are probably only geographical races of one species, representing in the trans-Missouri region the P. erythrophthalmus of the eastern division of the continent. It is true that specimens may be selected of the four races capable of accurate definition, but the transition from one to the other is so gradual that a considerable percentage of the collection can scarcely be assigned satisfactorily; and even if this were possible, the differences after all are only such as are caused by a slight change in the proportion of black, and the varying development of feet and wings.

Taking maculatus as it occurs in the central portion of its wide field of distribution, with wing-spots of average size, we find these spots slightly bordered, or at least often, with black, and the primaries edged externally with white only towards the end. The exterior web of lateral tail-feather is edged mostly with white; the terminal white patches of outer feather about an inch long; that of inner web usually separated from the outer by a black shaft-streak. In more northern specimens the legs are more dusky than usual. The tail is variable, but longer generally than in the other races. The claws are enormously large in many, but not in all specimens, varying considerably; and the fourth primary is usually longest, the first equal to or shorter than the secondaries. This is the race described as P. megalonyx, and characterizes the Middle Province, between the Sierra Nevada of California and the eastern Rocky Mountains, or the great interior basin of the continent; it occurs also near the head of the Rio Grande.

On the Pacific slope of California, as we proceed westward, we find a change in the species, the divergence increasing still more as we proceed northward, until in Oregon and Washington the extreme of range and alteration is seen in P. oregonus. Here the claws are much smaller, the white markings restricted in extent so as to form quite small spots bordered externally by black; the spots on the inner webs of tail much smaller, and even bordered along the shaft with black, and the outer web of the lateral entirely black, or with only a faint white edging. The concealed white of the head and neck has disappeared also.

Proceeding eastward, on the other hand, from our starting-point, we find another race, in P. arcticus, occupying the western slope of the Missouri Valley and the basin of the Saskatchewan, in which, on the contrary, the white increases in quantity, and more and more to its eastern limit. The black borders of the wing-patches disappear, leaving them white externally; and decided white edgings are seen for the first time at the bases of primaries, as well as near their ends, the two sometimes confluent. The terminal tail-patches are larger, the outer web of the exterior feather is entirely white except toward the very base, and we thus have the opposite extreme to P. oregonus. The wings are longer; the third primary longest; the first usually longer than the secondaries or the ninth quill.

Finally, proceeding southward along the table-lands of Mexico, and especially on their western slope, we find P. maculatus (the first described of all) colored much like the females of the more northern races, except that the head and neck are black, in decided contrast to the more olivaceous back. The wing formula and pattern of markings are much like megalonyx, the claws more like arcticus. Even in specimens of megalonyx, from the southern portion of its area of distribution, we find a tendency to an ashy or brownish tinge on the rump, extending more or less along the back; few, if any indeed, being uniformly black.

As, however, a general expression can be given to the variations referred to, and as they have an important geographical relationship, besides a general diagnosis, we give their characters and distribution in detail.

The general impression we derive from a study of the series is that the amount of white on the wing and elsewhere decreases from the Missouri River to the Pacific, exhibiting its minimum in Oregon and Washington, precisely as in the small black Woodpeckers; that in the Great Basin the size of the claws and the length of tail increases considerably; that the northern forms are entirely black, and the more southern brown or olivaceous, except on the head.

The following synopsis will be found to express the principal characteristics of the species and their varieties, premising that P. arcticus is more distinctly definable than any of the others. We add the character of the green-bodied Mexican species to complete the series.

Synopsis of VarietiesI. P. erythrophthalmus1. Wing, 3.65; tail, 4.20. Outer tail-feather with terminal half of inner web white. Iris bright red, sometimes paler. Hab. Eastern Province United States. (Florida in winter.) … var. erythrophthalmus.