полная версия

полная версияAmerican Institutions and Their Influence

127

See constitution, sect. 8. Federalist, Nos. 41 and 42. Kent's Commentaries, vol. i., p. 207. Story, pp. 358-382; 409-426.

128

Several other privileges of the same kind exist, such as that which empowers the Union to legislate on bankruptcy, to grant patents, and other matters in which its intervention is clearly necessary.

129

Even in these cases its interference is indirect. The Union interferes by means of the tribunals, as will be hereafter shown.

130

Federal Constitution, sect. 10, art. 1.

131

Constitution, sect. 8, 9, and 10. Federalist, Nos. 30-36 inclusive, and 41-44. Kent's Commentaries, vol. i., pp. 207 and 381. Story pp. 329 and 514.

132

Every ten years congress fixes anew the number of representatives which each state is to furnish. The total number was 69 in 1789, and 240 in 1833. (See American Almanac, 1834, p. 194.)

The constitution decided that there should not be more than one representative for every 30,000 persons; but no minimum was fixed upon. The congress has not thought fit to augment the number of representatives in proportion to the increase of population. The first act which was passed on the subject (14th April, 1792: see Laws of the United States, by Story, vol. i., p. 235) decided that there should be one representative for every 33,000 inhabitants. The last act, which was passed in 1822, fixes the proportion at one for 48,000. The population represented is composed of all the freemen and of three-fifths of the slaves.

133

See the Federalist, Nos. 52-66, inclusive. Story, pp. 199-314 Constitution of the United States, sections 2 and 3.

134

See the Federalist, Nos. 67-77. Constitution of the United States, a. t. 2. Story, pp. 115; 515-780. Kent's Commentaries, p. 255.

135

The constitution had left it doubtful whether the president was obliged to consult the senate in the removal as well as in the appointment of federal officers. The Federalist (No. 77) seemed to establish the affirmative; but in 1789, congress formally decided that as the president was responsible for his actions, he ought not to be forced to employ agents who had forfeited his esteem. See Kent's Commentaries, vol. i., p. 289.

136

The sums annually paid by the state to these officers amount to 200,000,000 francs (eight millions sterling).

137

This number is extracted from the "National Calendar," for 1833. The National Calendar is an American almanac which contains the names of all the federal officers.

It results from this comparison that the king of France has eleven times as many places at his disposal as the president, although the population of France is not much more than double that of the Union.

138

As many as it sends members to congress. The number of electors at the election of 1833 was 288. (See the National Calendar, 1833.)

139

The electors of the same state assemble, but they transmit to the central government the list of their individual votes, and not the mere result of the vote of the majority.

140

In this case it is the majority of the states, and not the majority of the members, which decides the question; so that New York has not more influence in the debate than Rhode Island. Thus the citizens of the Union are first consulted as members of one and the same community; and, if they cannot agree, recourse is had to the division of the states, each of which has a separate and independent vote. This is one of the singularities of the federal constitution which can only be explained by the jar of conflicting interests.

141

Jefferson, in 1801, was not elected until the thirty-sixth time of balloting.

142

See chapter vi., entitled, "Judicial Power in the United States." This chapter explains the general principles of the American theory of judicial institutions. See also the federal constitution, art. 3. See the Federalist, Nos. 78-83, inclusive: and a work entitled, "Constitutional Law, being a View of the Practice and Jurisdiction of the Courts of the United States," by Thomas Sergeant. See Story, pp. 134, 162, 489, 511, 581, 668; and the organic law of the 24th September, 1789, in the collection of the laws of the United States, by Story, vol. i., p. 53.

143

Federal laws are those which most require courts of justice, and those at the same time which have most rarely established them. The reason is that confederations have usually been formed by independent states, which entertained no real intention of obeying the central government, and which very readily ceded the right of commanding to the federal executive, and very prudently reserved the right of non-compliance to themselves.

144

The Union was divided into districts, in each of which a resident federal judge was appointed, and the court in which he presided was termed a "district court." Each of the judges of the supreme court annually visits a certain portion of the Republic, in order to try the most important causes upon the spot; the court presided over by this magistrate is styled a "circuit court." Lastly, all the most serious cases of litigation are brought before the supreme court, which holds a solemn session once a year, at which all the judges of the circuit courts must attend. The jury was introduced into the federal courts in the same manner, and in the same cases as into the courts of the states.

It will be observed that no analogy exists between the supreme court of the United States and the French cour de cassation, since the latter only hears appeals. The supreme court decides upon the evidence of the fact, as well as upon the law of the case, whereas the cour de cassation does not pronounce a decision of its own, but refers the cause to the arbitration of another tribunal. See the law of 24th September, 1789, laws of the United States, by Story, vol. i., p. 53.

145

In order to diminish the number of these suits, it was decided that in a great many federal causes, the courts of the states should be empowered to decide conjointly with those of the Union, the losing party having then a right of appeal to the supreme court of the United States. The supreme court of Virginia contested the right of the supreme court of the United States to judge an appeal from its decisions, but unsuccessfully. See Kent's Commentaries, vol. i., pp. 350, 370, et seq.; Story's Commentaries, p. 646; and "The Organic Law of the United States," vol. i., p. 35

146

The constitution also says that the federal courts shall decide "controversies between a state and the citizens of another state." And here a most important question of a constitutional nature arose, which was, whether the jurisdiction given by the constitution in cases in which a state is a party, extended to suits brought against a state as well as by it, or was exclusively confined to the latter. This question was most elaborately considered in the case of Chisholme v. Georgia, and was decided by the majority of the supreme court in the affirmative. The decision created general alarm among the states, and an amendment was proposed and ratified by which the power was entirely taken away so far as it regards suits brought against a state. See Story's Commentaries, p. 624, or in the large edition, § 1677.

147

As, for instance, all cases of piracy.

148

This principle was in some measure restricted by the introduction of the several states as independent powers into the senate, and by allowing them to vote separately in the house of representatives when the president is elected by that body; but these are exceptions, and the contrary principle is the rule.

149

It is perfectly clear, says Mr. Story (Commentaries, p. 503, or in the large edition, § 1379), that any law which enlarges, abridges, or in any manner changes the intention of the parties, resulting from the stipulations in the contract, necessarily impairs it. He gives in the same place a very long and careful definition of what is understood by a contract in federal jurisprudence. A grant made by the state to a private individual, and accepted by him, is a contract, and cannot be revoked by any future law. A charter granted by the state to a company is a contract, and equally binding to the state as to the grantee. The clause of the constitution here referred to ensures, therefore, the existence of a great part of acquired rights, but not of all. Property may legally be held, though it may not have passed into the possessor's hands by means of a contract; and its possession is an acquired right, not guaranteed by the federal constitution.

150

A remarkable instance of this is given by Mr. Story (p. 508, or in the large edition, § 1388). "Dartmouth college in New Hampshire had been founded by a charter granted to certain individuals before the American revolution, and its trustees formed a corporation under this charter. The legislature of New Hampshire had, without the consent of this corporation, passed an act changing the organization of the original provincial charter of the college, and transferring all the rights, privileges, and franchises, from the old charter trustees to new trustees appointed under the act. The constitutionality of the act was contested, and after solemn arguments, it was deliberately held by the supreme court that the provincial charter was a contract within the meaning of the constitution (art. i, sect. 10), and that the amendatory act was utterly void, as impairing the obligation of that charter. The college was deemed, like other colleges of private foundation, to be a private eleemosynary institution, endowed by its charter with a capacity to take property unconnected with the government. Its funds were bestowed upon the faith of the charter, and those funds consisted entirely of private donations. It is true that the uses were in some sense public, that is, for the general benefit, and not for the mere benefit of the corporators; but this did not make the corporation a public corporation. It was a private institution for general charity. It was not distinguishable in principle from a private donation, vested in private trustees, for a public charity, or for a particular purpose of beneficence. And the state itself, if it had bestowed funds upon a charity of the same nature, could not resume those funds."

151

See chapter vi., on judicial power in America.

152

See Kent's Commentaries, vol. i., p. 387.

153

At this time Alexander Hamilton, who was one of the principal founders of the constitution, ventured to express the following sentiments in the Federalist, No. 71: "There are some who would be inclined to regard the servile pliancy of the executive to a prevailing current, either in the community or in the legislature, as its best recommendation. But such men entertain very crude notions, as well of the purpose for which government was instituted, as of the true means by which the public happiness may be promoted. The republican principle demands that the deliberative sense of the community should govern the conduct of those to whom they intrust the managements of their affairs; but it does not require an unqualified complaisance to every sudden breeze of passion, or to every transient impulse which the people may receive from the arts of men who flatter their prejudices to betray their interests. It is a just observation that the people commonly intend the public good. This often applies to their very errors. But their good sense would despise the adulator who should pretend that they would always reason right, about the means of promoting it. They know from experience that they sometimes err; and the wonder is that they so seldom err as they do, beset, as they continually are, by the wiles of parasites and sycophants; by the snares of the ambitious, the avaricious, the desperate; by the artifices of men who possess their confidence more than they deserve it; and of those who seek to possess rather than to deserve it. When occasions present themselves in which the interests of the people are at variance with their inclinations, it is the duty of persons whom they have appointed to be the guardians of those interests, to withstand the temporary delusion, in order to give them time and opportunity for more cool and sedate reflection. Instances might be cited in which a conduct of this kind has saved the people from very fatal consequences of their own mistakes, and has procured lasting monuments of their gratitude to the men who had courage and magnanimity enough to serve at the peril of their displeasure."

154

This was the case in Greece, when Philip undertook to execute the decree of the Amphictyons; in the Low Countries, where the province of Holland always gave the law; and in our time in the Germanic confederation, in which Austria and Prussia assume a great degree of influence over the whole country, in the name of the Diet.

155

Such has always been the situation of the Swiss confederation, which would have perished ages ago but for the mutual jealousies of its neighbors.

156

I do not speak of a confederation of small republics, but of a great consolidated republic.

157

See the Mexican constitution of 1824.

158

For instance, the Union possesses by the constitution the right of selling unoccupied lands for its own profit. Supposing that the state of Ohio should claim the same right in behalf of certain territories lying within its boundaries, upon the plea that the constitution refers to those lands alone which do not belong to the jurisdiction of any particular state, and consequently should choose to dispose of them itself, the litigation would be carried on in the name of the purchasers from the state of Ohio, and the purchasers from the Union, and not in the names of Ohio and the Union. But what would become of this legal fiction if the federal purchaser was confirmed in his right by the courts of the Union, while the other competitor was ordered to retain possession by the tribunals of the state of Ohio?

{The difficulty supposed by the author in this note is imaginary. The question of title to the lands in the case put, must depend upon the constitution, treaties, and laws of the United States; and a decision in the state court adverse to the claim or title set up under those laws, must, by the very words of the constitution and of the judiciary act, be subject to review by the supreme court of the United States, whose decision is final.

The remarks in the text of this page upon the relative weakness of the government of the Union, are equally applicable to any form of republican or democratic government, and are not peculiar to a federal system. Under the circumstances supposed by the author, of all the citizens of a state, or a large majority of them, aggrieved at the same time and in the same manner, by the operation of any law, the same difficulty would arise in executing the laws of the state as those of the Union. Indeed, such instances of the total inefficacy of state laws are not wanting. The fact is, that all republics depend on the willingness of the people to execute the laws. If they will not enforce them, there is, so far, an end to the government, for it possesses no power adequate to the control of the physical power of the people.

Not only in theory, but in fact, a republican government must be administered by the people themselves. They, and they alone, must execute the laws. And hence, the first principles in such governments, that on which all others depend, and without which no other can exist, is and must be, obedience to the existing laws at all times and under all circumstances. It is the vital condition of the social compact. He who claims a dispensing power for himself, by which he suspends the operation of the law in his own case, is worse than a usurper, for he not only tramples under foot the constitution of his country, but violates the reciprocal pledge which he has given to his fellow-citizens, and has received from them, that he will abide by the laws constitutionally enacted; upon the strength of which pledge, his own personal rights and acquisitions are protected by the rest of the community.—American Editor.}

159

Kent's Commentaries, vol. i., p. 244. I have selected an example which relates to a time posterior to the promulgation of the present constitution. If I had gone back to the days of the confederation, I might have given still more striking instances. The whole nation was at that time in a state of enthusiastic excitement; the revolution was represented by a man who was the idol of the people; but at that very period congress had, to say the truth, no resources at all at its disposal. Troops and supplies were perpetually wanting. The best devised projects failed in the execution, and the Union, which was constantly on the verge of destruction, was saved by the weakness of its enemies far more than by its own strength.

160

Appendix O.

161

They only write in the papers when they choose to address the people in their own name; as, for instance, when they are called upon to repel calumnious imputations, and to correct a mis-statement of facts.

162

See Appendix P.

163

It may, however, be doubted whether this rational and self-guiding conviction arouses as much fervor or enthusiastic devotedness in men as their first dogmatical belief.

164

I here use the word magistrates in the widest sense in which it can be taken; I apply it to all the officers to whom the execution of the laws is intrusted.

165

See the act 27th February, 1813, General Collection of the Laws of Massachusetts, vol. ii., p. 331. It should be added that the Jurors are afterward drawn from these lists by lot.

166

See the act of 28th February, 1787, General Collection of the Laws of Massachusetts, vol. i., p. 302.

167

It is needless to observe, that I speak here of the democratic form of government as applied to a people, not merely to a tribe.

168

The word poor is used here, and throughout the remainder of this chapter, in a relative and not in an absolute sense. Poor men in America would often appear rich in comparison with the poor of Europe but they may with propriety be styled poor in comparison with their more affluent countrymen.

169

The easy circumstances in which secondary functionaries are placed in the United States, result also from another cause, which is independent of the general tendencies of democracy: every kind of private business is very lucrative, and the state would not be served at all if it did not pay its servants. The country is in the position of a commercial undertaking, which is obliged to sustain an expensive competition, notwithstanding its taste for economy.

170

The state of Ohio, which contains a million of inhabitants, gives its governor a salary of only $1,200 (260l.) a year.

171

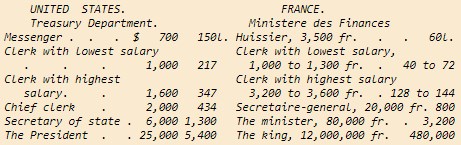

To render this assertion perfectly evident, it will suffice to examine the scale of salaries of the agents of the federal government. I have added the salaries attached to the corresponding officers in France, to complete the comparison:—

I have perhaps done wrong in selecting France as my standard of comparison. In France the democratic tendencies of the nation exercise an ever-increasing influence upon the government, and the chambers show a disposition to raise the lowest salaries and to lower the principal ones. Thus the minister of finance, who received 160,000 fr. under the empire, receives 80,000 fr., in 1835; the directeurs-generaux of finance, who then received 50,000 fr., now receive only 20,000 fr.

172

See the American budgets for the cost of indigent citizens and gratuitous instruction. In 1831, 50,000l. were spent in the state of New York for the maintenance of the poor; and at least 200,000l. were devoted to gratuitous instruction. (Williams's New York Annual Register, 1832, pp. 205, 243.) The state of New York contained only 1,900,000 inhabitants in the year 1830; which is not more than double the amount of population in the department du Nord in France.

173

The Americans, as we have seen, have four separate budgets; the Union, the states, the counties, and the townships, having each severally their own. During my stay in America I made every endeavor to discover the amount of the public expenditure in the townships and counties of the principal states of the Union, and I readily obtained the budget of the larger townships, but I found it quite impossible to procure that of the smaller ones. I possess, however, some documents relating to county expenses, which, although incomplete, are still curious. I have to thank Mr. Richards, mayor of Philadelphia, for the budgets of thirteen of the counties of Pennsylvania, viz.: Lebanon, Centre, Franklin, Fayette, Montgomery, Luzerne, Dauphin, Butler, Allegany, Columbia, Northampton, Northumberland, and Philadelphia, for the year 1830. Their population at that time consisted of 495,207 inhabitants. On looking at the map of Pennsylvania, it will be seen that these thirteen counties are scattered in every direction, and so generally affected by the causes which usually influence the condition of a country, that they may easily be supposed to furnish a correct average of the financial state of the counties of Pennsylvania in general; and thus, upon reckoning that the expenses of these counties amounted in the year 1830 to about 72,330l., or nearly 3s. for each inhabitant, and calculating that each of them contributed in the same year about 10s. 2d. toward the Union, and about 3s. to the state of Pennsylvania, it appears that they each contributed as their share of all the public expenses (except those of the townships), the sum of 16s. 2d. This calculation is doubly incomplete, as it applies only to a single year and to one part of the public charges; but it has at least the merit of not being conjectural.

174

Those who have attempted to draw a comparison between the expenses of France and America, have at once perceived that no such comparison could be drawn between the total expenditures of the two countries; but they have endeavored to contrast detached portions of this expenditure. It may readily be shown that this second system is not at all less defective than the first.

175

Even if we knew the exact pecuniary contributions of every French and American citizen to the coffers of the state, we should only come at a portion of the truth. Governments not only demand supplies of money, but they call for personal services, which may be looked upon as equivalent to a given sum. When a state raises an army, beside the pay of the troops which is furnished by the entire nation, each soldier must give up his time, the value of which depends on the use he might make of it if he were not in the service. The same remark applies to the militia: the citizen who is in the militia devotes a certain portion of valuable time to the maintenance of the public peace, and he does in reality surrender to the state those earnings which he is prevented from gaining. Many other instances might be cited in addition to these. The governments of France and America both levy taxes of this kind, which weigh upon the citizens; but who can estimate with accuracy their relative amount in the two countries?