полная версия

полная версияStory of the Bible Animals

Before concluding this necessarily short account of the domesticated oxen of Palestine, it will be needful to give a few lines to the animal viewed in a religious aspect. Here we have, in bold contrast to each other, the divine appointment of certain cattle to be slain as sacrifices, and the reprobation of worship paid to those very cattle as living emblems of divinity. This false worship was learned by the Israelites during their long residence in Egypt, and so deeply had the customs of the Egyptian religion sunk into their hearts, that they were not eradicated after the lapse of centuries. It may easily be imagined that such a superstition, surrounded as it was with every external circumstance which could make it more imposing, would take a powerful hold of the Jewish mind.

Chief among the multitude of idols or symbols was the god Apis, represented by a bull. Many other animals, specially the cat and the ibis, were deeply honoured among the ancient Egyptians, as we learn from their own monuments and from the works of the old historians. All these creatures were symbols as well as idols, symbols to the educated and idols to the ignorant.

None of them was held in such universal honour as the bull Apis. The particular animal which represented the deity, and which was lodged with great state and honour in his temple at Memphis, was thought to be divinely selected for the purpose, and to be impressed with certain marks. His colour must be black, except a square spot on the forehead, a crescent-shaped white spot on the right side, and the figure of an eagle on his back. Under the tongue must be a knob shaped like the sacred scarabæus, and the hairs of his tail must be double.

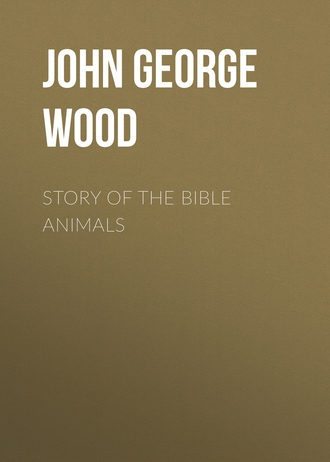

MUMMY OF A SACRED BULL TAKEN FROM AN EGYPTIAN TOMB.

This representative animal was only allowed to live for a certain time, and when he had reached this allotted period, he was taken in solemn procession to the Nile, and drowned in its sacred waters. His body was then embalmed, and placed with great state in the tombs at Memphis.

After his death, whether natural or not, the whole nation went into mourning, and exhibited all the conventional signs of sorrow, until the priests found another bull which possessed the distinctive marks. The people then threw off their mourning robes, and appeared in their best attire, and the sacred bull was exhibited in state for forty days before he was taken to his temple at Memphis. The reader will here remember the analogous case of the Indian cattle, some of which are held to be little less than incarnations of divinity.

Even at the very beginning of the exodus, when their minds must have been filled with the many miracles that had been wrought in their behalf, and with the cloud and fire of Sinai actually before their eyes, Aaron himself made an image of a calf in gold, and set it up as a symbol of the Lord. That the idol in question was intended as a symbol by Aaron is evident from the words which he used when summoning the people to worship, "To-morrow is a feast of the Lord" (Gen. xxxii. 5). The people, however, clearly lacked the power of discriminating between the symbol and that which it represented, and worshipped the image just as any other idol might be worshipped. And, in spite of the terrible and swift punishment that followed, and which showed the profanity of the act, the idea of ox-worship still remained among the people.

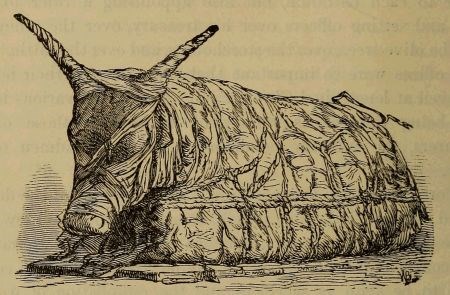

ANIMALS BEING SOLD FOR SACRIFICE IN THE PORCH OF THE TEMPLE.

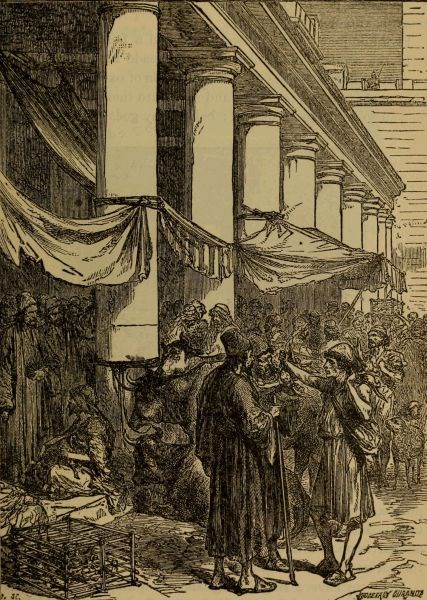

JEROBOAM SETS UP A GOLDEN CALF AT BETHEL.

Five hundred years afterwards we find a familiar example of it in the conduct of Jeroboam, "who made Israel to sin," the peculiar crime being the open resuscitation of ox-worship. "The king made two calves of gold and said unto them, It is too much for you to go up to Jerusalem: behold thy gods, O Israel, which brought thee up out of the land of Egypt. And he set the one in Bethel, and the other put he in Dan.... And he made an house of high places, and made priests of the lowest of the people, which were not of the tribe of Levi. And Jeroboam ordained a feast … like unto the feast in Judah, and he offered upon the altar. So did he in Bethel, sacrificing unto the calves that he had made."

Here we have a singular instance of a king of Israel repeating, after a lapse of five hundred years, the very acts which had drawn down on the people so severe a punishment, and which were so contrary to the law that they had incited Moses to fling down and break the sacred tables on which the commandments had been divinely inscribed.

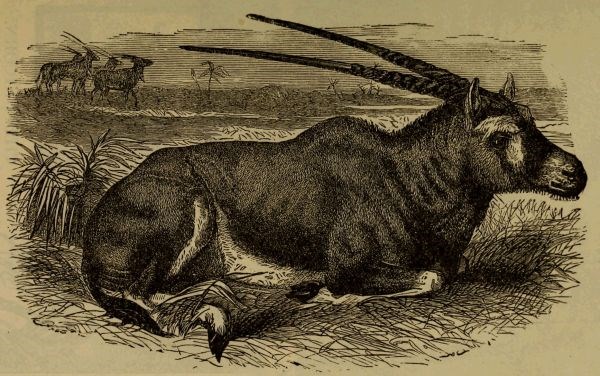

THE BUFFALO.

Another species of the ox-tribe now inhabits Palestine though commentators rather doubt whether it is not a comparatively late importation. This is the true Buffalo (Bubalus buffelus, Gray), which is spread over a very large portion of the earth, and is very plentiful in India. In that country there are two distinct breeds of the Buffalo, namely, the Arnee, a wild variety, and the Bhainsa, a tamed variety. The former animal is much larger than the latter, being sometimes more than ten feet in length from the nose to the root of the tail, and measuring between six and seven feet in height at the shoulder. Its horns are of enormous length, the tail is very short, and tufts of hair grow on the forehead and horns. The tamed variety is at least one-third smaller, and, unlike the Arnee, never seems to get into high condition. It is an ugly, ungainly kind of beast, and is rendered very unprepossessing to the eye by the bald patches which are mostly found upon its hide.

Being a water-loving animal, the Buffalo always inhabits the low-lying districts, and is fond of wallowing in the oozy marshes in which it remains for hours, submerged all but its head, and tranquilly chewing the cud while enjoying its mud-bath. While thus engaged the animal depresses its horns so that they are scarcely visible, barely allowing more than its eyes, ears, and nostrils to remain above the surface, so that the motionless heads are scarcely distinguishable from the grass and reed tufts which stud the marshes. Nothing is more startling to an inexperienced traveller than to pass by a silent and tranquil pool where the muddy surface is unbroken except by a number of black lumps and rushy tufts, and then to see these tufts suddenly transformed into twenty or thirty huge beasts rising out of the still water as if by magic. Generally, the disturber of their peace had better make the best of his way out of their reach, as the Buffalo, whether wild or tame, is of a tetchy and irritable nature, and resents being startled out of its state of dreamy repose.

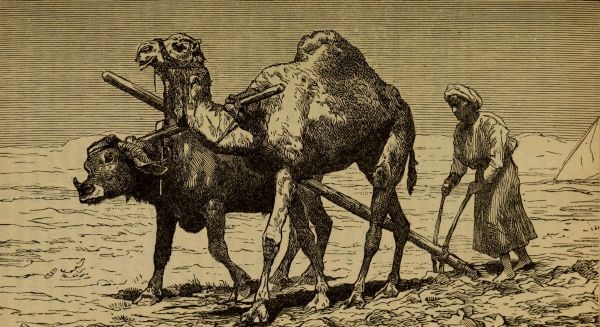

In the Jordan valley the Buffalo is found, and is used for agriculture, being of the Bhainsa, or domesticated variety. Being much larger and stronger than the ordinary cattle, it is useful in drawing the plough, but its temper is too uncertain to render it a pleasant animal to manage. As is the case with all half-wild cattle, its milk is very scanty, but compensates by the richness of the quality for the lack of quantity.

In the picture which appears on a following page, one of these domesticated Buffaloes is represented, harnessed with a camel, to a rude form of plough used in the East.

THE BHAINSA, OR DOMESTIC BUFFALO, AND CAMEL, DRAWING THE PLOUGH.

THE WILD BULL

The Tô, Wild Bull of the Old Testament—Passages in which it is mentioned—The Wild Bull in the net—Hunting with nets in the East—The Oryx supposed to be the Tô of Scripture—Description of the Oryx, its locality, appearance, and habits—The points in which the Oryx agrees with the Tô—The "snare" in which the foot is taken, as distinguished from the net.

In two passages of the Old Testament an animal is mentioned, respecting which the translators and commentators have been somewhat perplexed, in one passage being translated as the "Wild Ox," and in the other as the "Wild Bull." In the Jewish Bible the same rendering is preserved, but the sign of doubt is added to the word in both cases, showing that the translation is an uncertain one.

The first of these passages occurs in Deut. xiv. 5, where it is classed together with the ox, sheep, goats, and other ruminants, as one of the beasts which were lawful for food. Now, although we cannot identify it by this passage, we can at all events ascertain two important points—the first, that it was a true ruminant, and the second, that it was not the ox, the sheep, or the goat. It was, therefore, some wild ruminant, and we now have to ask how we are to find out the species.

If we turn to Isa. li. 20, we shall find a passage which will help us considerably. Addressing Jerusalem, the prophet uses these words, "By whom shall I comfort thee? Thy sons have fainted, they lie at the head of all the streets, as a wild bull in a net; they are full of the fury of the Lord, the rebuke of thy God." We now see that the Tô or Teô must be an animal which is captured by means of nets, and therefore must inhabit spots wherein the toils can be used. Moreover, it is evidently a powerful animal, or the force of the simile would be lost. The prophet evidently refers to some large and strong beast which has been entangled in the hunter's nets, and which lies helplessly struggling in them. We are, therefore, almost perforce driven to recognise it as some large antelope.

The expression used by the prophet is so characteristic that it needs a short explanation. In this country, and at the present day, the use of the net is almost entirely restricted to fishing and bird-catching; but in the East nets are still employed in the capture of very large game.

A brief allusion to the hunting-net is made at page 31, but, as the passage in Isaiah li. requires a more detailed account of this mode of catching large animals, it will be as well to describe the sport as at present practised in the East.

When a king or some wealthy man determines to hunt game without taking much trouble himself, he gives orders to his men to prepare their nets, which vary in size or strength according to the particular animal for which they are intended. If, for example, only the wild boar and similar animals are to be hunted, the nets need not be of very great width; but for agile creatures, such as the antelope, they must be exceedingly wide, or the intended prey will leap over them. As the net is much used in India for the purpose of catching game, Captain Williamson's description of it will explain many of the passages of Scripture wherein it is mentioned.

The material of the net is hemp, twisted loosely into a kind of rope, and the mode in which it is formed is rather peculiar. The meshes are not knotted together, but only twisted round each other, much after the fashion of the South American hammocks, so as to obtain considerable elasticity, and to prevent a powerful animal from snapping the cord in its struggles. Some of these nets are thirteen feet or more in width, and even such a net as this has been overleaped by a herd of antelopes. Their length is variable, but, as they can be joined in any number when set end to end, the length is not so important as the width.

The mode of setting the nets is singularly ingenious. When a suitable spot has been selected, the first care of the hunters is to stretch a rope as tightly as possible along the ground. For this purpose stout wooden stakes or truncheons are sunk crosswise in the earth, and between these the rope is carefully strained. The favourite locality of the net is a ravine, through which the animals can be driven so as to run against the net in their efforts to escape, and across the ravine a whole row of these stakes is sunk. The net is now brought to the spot, and its lower edge fastened strongly to the ground rope.

The strength of this mode of fastening is astonishing, and, although the stakes are buried scarcely a foot below the surface, they cannot be torn up by any force which can be applied to them; and, however strong the rope may be, it would be broken before the stakes could be dragged out of the ground.

A smaller rope is now attached to the upper edge of the net, which is raised upon a series of slight poles. It is not stretched quite tightly, but droops between each pair of poles, so that a net which is some thirteen feet in width will only give nine or ten feet of clear height when the upper edge is supported on the poles. These latter are not fixed in the ground, but merely held in their places by the weight of the net resting upon them.

When the nets have been properly set, the beaters make a wide circuit through the country, gradually advancing towards the fatal spot, and driving before them all the wild animals that inhabit the neighbourhood. As soon as any large beast, such, for example, as an antelope, strikes against the net, the supporting pole falls, and the net collapses upon the unfortunate animal, whose struggles—especially if he be one of the horned animals—only entangle him more and more in the toils.

As soon as the hunters see a portion of the net fall, they run to the spot, kill the helpless creature that lies enveloped in the elastic meshes, drag away the body, and set up the net again in readiness for the next comer. Sometimes the line of nets will extend for half a mile or more, and give employment to a large staff of hunters, in killing the entangled animals, and raising afresh those portions of the net which had fallen.

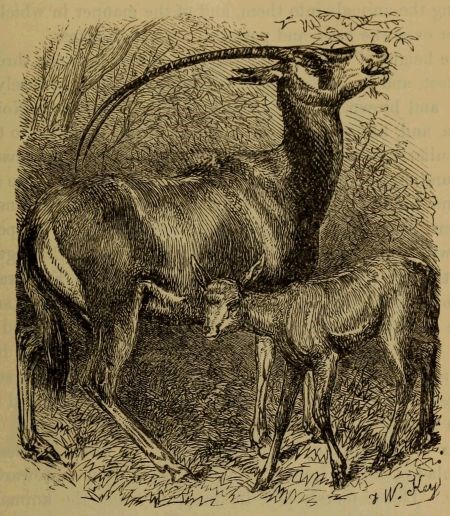

Accepting the theory that the Tô is one of the large antelopes that inhabit, or used to inhabit, the Holy Land and its neighbourhood, we may safely conjecture that it may signify the beautiful animal known as the Oryx (Oryx leucoryx), an animal which has a tolerably wide range, and is even now found on the borders of the Holy Land. It is a large and powerful antelope, and is remarkable for its beautiful horns, which sometimes exceed a yard in length, and sweep in a most graceful curve over the back.

Sharp as they are, and evidently formidable weapons, the manner in which they are set on the head renders them apparently unserviceable for combat. When, however, the Oryx is brought to bay, or wishes to fight, it stoops its head until the nose is close to the ground, the points of the horns being thus brought to the front. As the head is swung from side to side, the curved horns sweep through a considerable space, and are so formidable that even the lion is chary of attacking their owner. Indeed, instances are known where the lion has been transfixed and killed by the horns of the Oryx. Sometimes the animal is not content with merely standing to repel the attacks of its adversaries, but suddenly charges forward with astonishing rapidity, and strikes upwards with its horns as it makes the leap.

WILD BULL, OR ORYX.

But these horns, which can be used with such terrible effect in battle, are worse than useless when the animal is hampered in the net. In vain does the Oryx attempt its usual defence: the curved horns get more and more entangled in the elastic meshes, and become a source of weakness rather than strength. We see now how singularly appropriate is the passage, "Thy sons lie at the heads of all the streets, as a wild bull (or Oryx) in a net," and how completely the force of the metaphor is lost without a knowledge of the precise mode of fixing the nets, of driving the animals into them, and of the manner in which they render even the large and powerful animals helpless.

The height of the Oryx at the shoulder is between three and four feet, and its colour is greyish white, mottled profusely with black and brown in bold patches. It is plentiful in Northern Africa, and, like many other antelopes, lives in herds, so that it is peculiarly suited to that mode of hunting which consists in surrounding a number of animals, and driving them into a trap of some kind, whether a fenced enclosure, a pitfall, or a net.

There is, by the way, the term "snare," which is specially used with especial reference to catching the foot as distinguished from the net which enveloped the whole body. For example, in Job xviii. 8, "He is cast into a net, he walketh on a snare," where a bold distinction is drawn between the two and their mode of action. And in ver. 10, "The snare is laid for him in the ground." Though I would not state definitely that such is the case, I believe that the snare which is here mentioned is one which is still used in several parts of the world.

It is simply a hoop, to the inner edge of which are fastened a number of elastic spikes, the points being directed towards the centre. This is merely laid in the path which the animal will take, and is tied by a short cord to a log of wood. As the deer or antelope treads on the snare, the foot passes easily through the elastic spikes, but, when the foot is raised, the spikes run into the joint and hold the hoop upon the limb. Terrified by the check and the sudden pang, the animal tries to run away, but, by the united influence of sharp spikes and the heavy log, it is soon forced to halt, and so becomes an easy prey to its pursuers.

THE ORYX.

THE UNICORN

The Unicorn apparently known to the Jews—Its evident connection with the Ox tribe—Its presumed identity with the now extinct Urus—Enormous size and dangerous character of the Urus.

There are many animals mentioned in the Scriptures which are identified with difficulty, partly because their names occur only once or twice in the sacred writings, and partly because, when they are mentioned, the context affords no clue to their identity by giving any hint as to their appearance or habits. In such cases, although the translators would have done better if they had simply given the Hebrew word without endeavouring to identify it with any known animal, they may be excused for committing errors in their nomenclature. There is one animal, however, for which no such excuse can be found, and this is the Reêm of Scripture, translated as Unicorn in the authorized version.

Even in late years the Unicorn has been erroneously supposed to be identical with the Rhinoceros of India. It is, however, now certain that the Unicorn was not the Rhinoceros, and that it can be almost certainly identified with an animal which, at the time when the passages in question were written, was plentiful in Palestine, although, like the Lion, it is now extinct.

On turning to the Jewish Bible we find that the word Reêm is translated as buffalo, and there is no doubt that this rendering is nearly the correct one. At the present day naturalists are nearly all agreed that the Unicorn of the Old Testament must have been of the Ox tribe. Probably the Urus, a species now extinct, was the animal alluded to. A smaller animal, the Bonassus or Bison, also existed in Palestine, and even to the present day continues to maintain itself in one or two spots, though it will probably be as soon completely erased from the surface of the earth as its gigantic congener.

That the Unicorn was one of the two animals is certain, and that it was the larger is nearly as certain. The reason for deciding upon the Urus is, that its horns were of great size and strength, and therefore agree with the description of the Unicorn; whereas those of the Bonassus, although powerful, are short, and not conspicuous enough to deserve the notice which is taken of them by the sacred writers.

Of the extinct variety we know but little. We do know, however, that it was a huge and most formidable beast, as is evident from the skulls and other bones which have been discovered. Their character also indicates that the creature was nothing more than a very large Ox, probably measuring twelve feet in length, and six feet in height. Such a wild animal, armed, as it was, with enormous horns, would prove a most formidable antagonist.

THE BISON

The Bison tribe and its distinguishing marks—Its former existence in Palestine—Its general habits—Origin of its name—Its musky odour—Size and speed of the Bison—Its dangerous character when brought to bay—Its defence against the wolf—Its untameable disposition.

A few words are now needful respecting the second animal which has been mentioned in connexion with the Reêm; namely, the Bison, or Bonassus. The Bisons are distinguishable from ordinary cattle by the thick and heavy mane which covers the neck and shoulders, and which is more conspicuous in the male than in the female. The general coating of the body is also rather different, being thick and woolly instead of lying closely to the skin like that of the other oxen. The Bison certainly inhabited Palestine, as its bones have been found in that country. It has, however, been extinct in the Holy Land for many years, and, not being an animal that is capable of withstanding the encroachments of man, it has gradually died out from the greater part of Europe and Asia, and is now to be found only in a very limited locality, chiefly in a Lithuanian forest, where it is strictly preserved, and in some parts of the Caucasus. There it still preserves the habits which made its ancient and gigantic relative so dangerous an animal. Unlike the buffalo, which loves the low-lying and marshy lands, the Bison prefers the high wooded localities, where it lives in small troops.

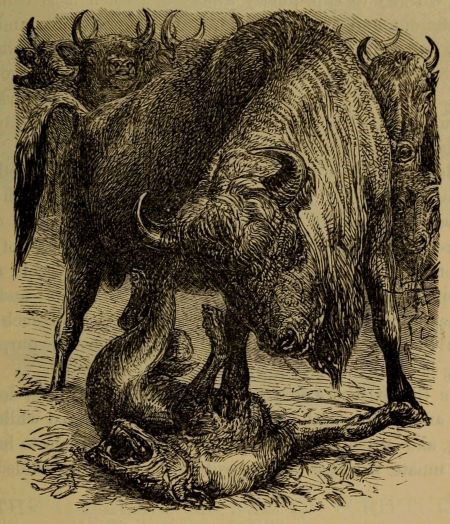

BISON KILLING WOLF.

Its name of Bison is a modification of the word Bisam, or musk, which was given to it on account of the strong musky odour of its flesh, which is especially powerful about the head and neck. This odour is not so unpleasant as might be supposed, and those who have had personal experience of the animal say that it bears some resemblance to the perfume of violets. It is developed most strongly in the adult bulls, the cows and young male calves only possessing it in a slight degree.

It is a tolerably large animal, being about six feet high at the shoulder—a stature nearly equivalent to that of the ordinary Asiatic elephant; and, in spite of its great bulk, is a fleet and active animal, as indeed is generally the case with those oxen which inhabit elevated localities. Still, though it can run with considerable speed, it is not able to keep up the pace for any great distance, and at the end of a mile or two can be brought to bay.

Like most animals, however large and powerful they may be, it fears the presence of man, and, if it sees or scents a human being, will try to slip quietly away; but when it is baffled in this attempt, and forced to fight, it becomes a fierce and dangerous antagonist, charging with wonderful quickness, and using its short and powerful horns with great effect. A wounded Bison, when fairly brought to bay, is perhaps as awkward an opponent as can be found, and to kill it without the aid of firearms is no easy matter.

Although the countries in which it lives are infested with wolves, it seems to have no fear of them when in health; and, even when pressed by their winter's hunger, the wolves do not venture to attack even a single Bison, much less a herd of them. Like other wild cattle, it likes to dabble in muddy pools, and is fond of harbouring in thickets near such localities; and those who have to travel through the forest keep clear of such spots, unless they desire to drive out the animal for the purpose of killing it.

Like the extinct Aurochs, the Bison has never been domesticated, and, although the calves have been captured while very young, and attempts have been made to train them to harness, their innate wildness of disposition has always baffled such efforts.