полная версия

полная версияStory of the Bible Animals

THE GAZELLE, OR ROE OF SCRIPTURE

Its swiftness, its beauty, and the quality of its flesh—Different varieties of the Gazelle—How the Gazelle defends itself against wild beasts—Chase of the Gazelle.

We now leave the Ox tribe, and come to the Antelopes, several species of which are mentioned in the Scriptures. Four kinds of antelope are found in or near the Holy Land, and there is little doubt that all of them are mentioned in the sacred volume.

The first that will be described is the Gazelle, which is acknowledged to be the animal that is represented by the word Tsebi, or Tsebiyah. The Jewish Bible accepts the same rendering. This word occurs many times, sometimes as a metaphor, and sometimes representing some animal which was lawful food, and which therefore belonged to the true ruminants. Moreover, its flesh was not only legally capable of being eaten, but was held in such estimation that it was provided for the table of Solomon himself, together with other animals which will be described in their turn.

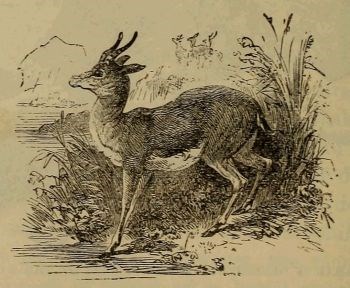

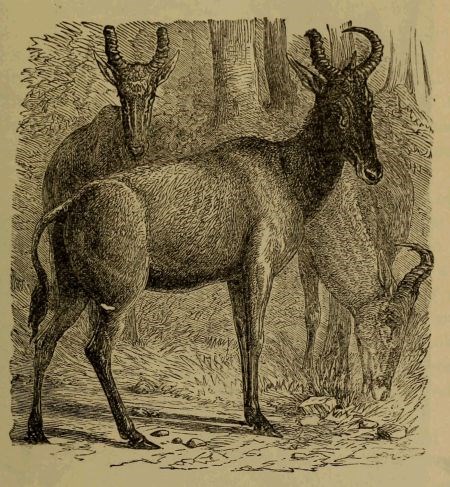

THE GAZELLE.

It is even now considered a great dainty, although it is not at all agreeable to European taste, being hard, dry, and without flavour. Still, as has been well remarked, tastes differ as well as localities, and an article of food which is a costly luxury in one land is utterly disdained in another, and will hardly be eaten except by one who is absolutely dying of starvation.

The Gazelle is very common in Palestine in the present day, and, in the ancient times, must have been even more plentiful. There are several varieties of it, which were once thought to be distinct species, but are now acknowledged to be mere varieties, all of which are referable to the single species Gazella Dorcas. There is, for example, the Corinna, or Corine Antelope, which is a rather boldly-spotted female; the Kevella Antelope, in which the horns are slightly flattened; the small variety called the Ariel, or Cora; the grey Kevel, which is a rather large variety; and the Long-horned Gazelle, which owes its name to a rather large development of the horns.

Whatever variety may inhabit any given spot, they all have the same habits. They are gregarious animals, associating together in herds often of considerable size, and deriving from their numbers an element of strength which would otherwise be wanting. Against mankind, numbers are of no avail; but when the agile though feeble Gazelle has to defend itself against the predatory animals of its own land, it can only defend itself by the concerted action of the whole herd. Should, for example, the wolves prowl round a herd of Gazelles, after their treacherous wont, the Gazelles instantly assume a posture of self-defence. They form themselves into a compact phalanx, all the males coming to the front, and the strongest and boldest taking on themselves the honourable duty of facing the foe. The does and the young are kept within their ranks, and so formidable is the array of sharp, menacing horns, that beasts as voracious as the wolf, and far more powerful, have been known to retire without attempting to charge.

As a rule, however, the Gazelle does not desire to resist, and prefers its legs to its horns as a mode of insuring safety. So fleet is the animal, that it seems to fly over the ground as if propelled by volition alone, and its light, agile frame is so enduring, that a fair chase has hardly any prospect of success. Hunters, therefore, prefer a trap of some kind, if they chase the animal merely for food or for the sake of its skin, and contrive to kill considerable numbers at once. Sometimes they dig pitfalls, and drive the Gazelles into them by beating a large tract of country, and gradually narrowing the circle. Sometimes they use nets, such as have already been described, and sometimes they line the sides of a ravine with archers and spearmen, and drive the herd of Gazelles through the treacherous defile.

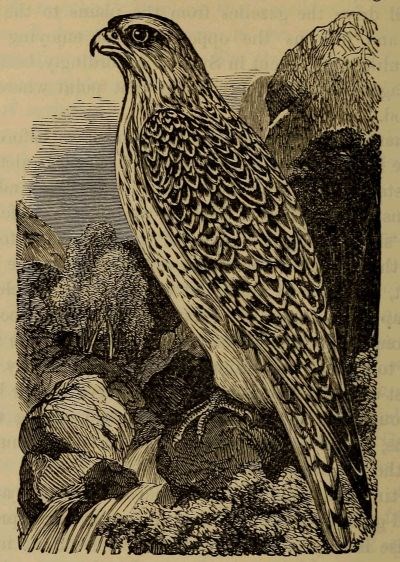

These modes of slaughter are, however, condemned by the true hunter, who looks upon those who use them much in the same light as an English sportsman looks on a man who shoots foxes. The greyhound and the falcon are both employed in the legitimate capture of the Gazelle, and in some cases both are trained to work together. Hunting the Gazelle with the greyhound very much resembles coursing in our own country, and chasing it with the hawk is exactly like the system of falconry that was once so popular an English sport, and which even now shows signs of revival.

It is, however, when the dog and the bird are trained to work together that the spectacle becomes really novel and interesting to an English spectator.

As soon as the Gazelles are fairly in view, the hunter unhoods his hawk, and holds it up so that it may see the animals. The bird fixes its eye on one Gazelle, and by that glance the animal's doom is settled. The falcon darts after the Gazelles, followed by the dog, who keeps his eye on the hawk, and holds himself in readiness to attack the animal that his feathered ally may select. Suddenly the falcon, which has been for some few seconds hovering over the herd of Gazelles, makes a stoop upon the selected victim, fastening its talons in its forehead, and, as it tries to shake off its strange foe, flaps its wings into the Gazelle's eyes so as to blind it. Consequently, the rapid course of the antelope is arrested, so that the dog is able to come up and secure the animal while it is struggling to escape from its feathered enemy. Sometimes, though rarely, a young and inexperienced hawk swoops down with such reckless force that it misses the forehead of the Gazelle, and impales itself upon the sharp horns, just as in England the falcon is apt to be spitted on the bill of the heron.

The most sportsmanlike mode of hunting the Gazelle is to use the falcon alone; but for this sport a bird must possess exceptional strength, swiftness, and intelligence. A very spirited account of such a chase is given by Mr. G. W. Chasseaud, in his "Druses of the Lebanon:"—

"Whilst reposing here, our old friend with the falcon informs us that at a short distance from this spot is a khan called Nebbi Youni, from a supposition that the prophet Jonah was here landed by the whale; but the old man is very indignant when we identify the place with a fable, and declare to him that similar sights are to be seen at Gaza and Scanderoon. But his good humour is speedily recovered by reverting to the subject of the exploits and cleverness of his falcon. This reminds him that we have not much time to waste in idle talk, as the greater heats will drive the gazelles from the plains to the mountain retreats, and lose us the opportunity of enjoying the most sportsmanlike amusement in Syria. Accordingly, bestriding our animals again, we ford the river at that point where a bridge once stood.

"We have barely proceeded twenty minutes before the keen eye of the falconer has descried a herd of gazelles quietly grazing in the distance. Immediately he reins in his horse, and enjoining silence, instead of riding at them, as we might have felt inclined to do, he skirts along the banks of the river, so as to cut off, if possible, the retreat of these fleet animals where the banks are narrowest, though very deep, but which would be cleared at a single leap by the gazelles. Having successfully accomplished this manœuvre, he again removes the hood from the hawk, and indicates to us that precaution is no longer necessary. Accordingly, first adding a few slugs to the charges in our barrels, we balance our guns in an easy posture, and, giving the horses their reins, set off at full gallop, and with a loud hurrah, right towards the already startled gazelles.

"The timid animals, at first paralysed by our appearance, stand and gaze for a second terror-stricken at our approach; but their pause is only momentary; they perceive in an instant that the retreat to their favourite haunts has been secured, and so they dash wildly forward with all the fleetness of despair, coursing over the plain with no fixed refuge in view, and nothing but their fleetness to aid in their delivery. A stern chase is a long chase, and so, doubtless, on the present occasion it would prove with ourselves, for there is many and many a mile of level country before us, and our horses, though swift of foot, stand no chance in this respect with the gazelles.

"Now, however, the old man has watched for a good opportunity to display the prowess and skill of his falcon: he has followed us only at a hand-gallop; but the hawk, long inured to such pastime, stretches forth its neck eagerly in the direction of the flying prey, and being loosened from its pinions, sweeps up into the air like a shot, and passes overhead with incredible velocity. Five minutes more, and the bird has outstripped even the speed of the light-footed gazelle; we see him through the dust and haze that our own speed throws around us, hovering but an instant over the terrified herd; he has singled out his prey, and, diving with unerring aim, fixes his iron talons into the head of the terrified animal.

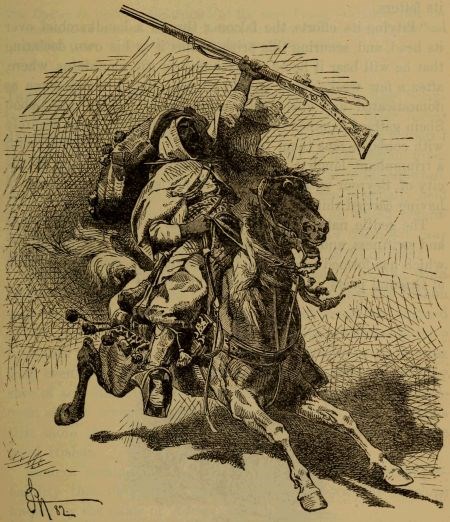

THE FALCON USED IN OUR HUNT.

"This is the signal for the others to break up their orderly retreat, and to speed over the plain in every direction. Some, despite the danger that hovers on their track, make straight for their old and familiar haunts, and passing within twenty yards of where we ride, afford us an opportunity of displaying our skill as amateur huntsmen on horseback; nor does it require but little nerve and dexterity to fix our aim whilst our horses are tearing over the ground. However, the moment presents itself, the loud report of barrel after barrel startles the unaccustomed inmates of that unfrequented waste; one gazelle leaps twice its own height into the air, and then rolls over, shot through the heart; another bounds on yet a dozen paces, but, wounded mortally, staggering, halts, and then falls to the ground.

"This is no time for us to pull in and see what is the amount of damage done, for the falcon, heedless of all surrounding incidents, clings firmly to the head of its terrified victim, flapping its strong wings awhile before the poor brute's terrified eyes, half blinding it and rendering its head dizzy; till, after tearing round and round with incredible speed, the poor creature stops, panting for breath, and, overcome with excessive terror, drops down fainting upon the earth. Now the air resounds with the acclamations and hootings of the ruthless victors.

THE ARAB IS DELIGHTED AT THE SUCCESS OF THE HUNT.

"The Arab is wild in his transports of delight. More certain of the prowess of his bird than ourselves, he had stopped awhile to gather together the fruits of our booty, and now galloped furiously up, waving his long gun, and shouting lustily the while the praises of his infallible hawk; then getting down, and hoodwinking the bird again, he first of all takes the precaution of fastening together the legs of the fallen gazelle, and then he humanely blows up into its nostrils. Gradually the natural brilliancy returns to the dimmed eyes of the gazelle, then it struggles valiantly, but vainly, to disentangle itself from its fetters.

"Pitying its efforts, the falconer throws a handkerchief over its head, and, securing this prize, claims it as his own, declaring that he will bear it home to his house in the mountains, where, after a few weeks' kind treatment and care, it will become as domesticated and affectionate as a spaniel. Meanwhile, Abou Shein gathers together the fallen booty, and, tying them securely with cords, fastens them behind his own saddle, declaring, with a triumphant laugh, that we shall return that evening to the city of Beyrout with such game as few sportsmen can boast of having carried thither in one day."

The gentle nature of the Gazelle is as proverbial as its grace and swiftness, and is well expressed in the large, soft, liquid eye, which has formed from time immemorial the stock comparison of Oriental poets when describing the eyes of beauty.

THE GAZELLE.

THE PYGARG, OR ADDAX

The Dishon or Dyshon—Signification of the word Pygarg—Certainty that the Dishon is an antelope, and that it must be one of a few species—Former and present range of the Addax—Description of the Addax.

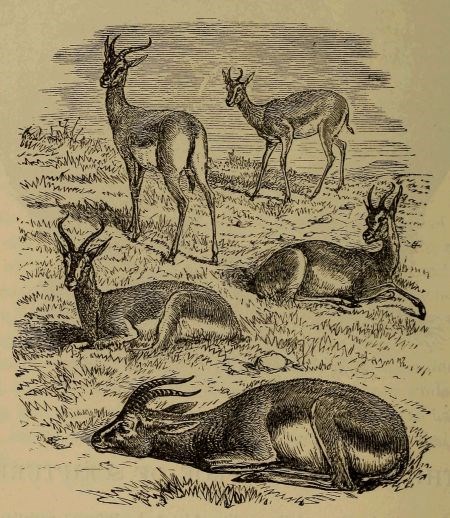

There is a species of animal mentioned once in the Scriptures under the name of Dishon which the Jewish Bible leaves untranslated, and merely gives as Dyshon, and which is rendered in the Septuagint by Pugargos, or Pygarg, as one version gives it. Now, the meaning of the word Pygarg is white-crouped, and for that reason the Pygarg of the Scriptures is usually held to be one of the white-crouped antelopes, of which several species are known. Perhaps it may be one of them—it may possibly be neither, and it may probably refer to all of them.

But that an antelope of some kind is meant by the word Dishon is evident enough, and it is also evident that the Dishon must have been one of the antelopes which could be obtained by the Jews. Now as the species of antelope which could have furnished food for that nation are very few in number, it is clear that, even if we do not hit upon the exact species, we may be sure of selecting an animal that was closely allied to it. Moreover, as the nomenclature is exceedingly loose, it is probable that more than one species might have been included in the word Dishon.

Modern commentators have agreed that there is every probability that the Dishon of the Pentateuch was the antelope known by the name of Addax.

This handsome antelope is a native of Northern Africa. It has a very wide range, and, even at the present day, is found in the vicinity of Palestine, so that it evidently was one of the antelopes which could be killed by Jewish hunters. From its large size, and long twisted horns, it bears a strong resemblance to the Koodoo of Southern Africa. The horns, however, are not so long, nor so boldly twisted, the curve being comparatively slight, and not possessing the bold spiral shape which distinguishes those of the koodoo.

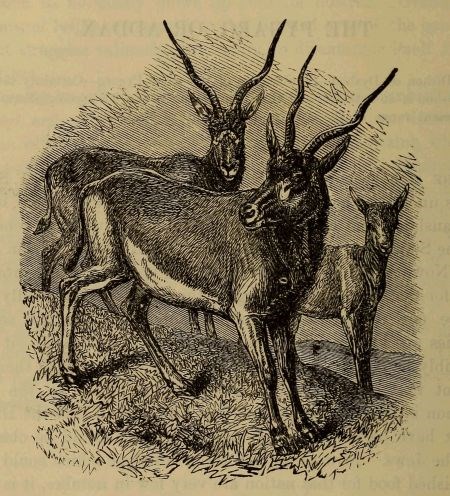

THE ADDAX.

The ordinary height of the Addax is three feet seven or eight inches, and the horns are almost exactly alike in the two sexes. Their length, from the head to the tips, is rather more than two feet. Its colour is mostly white, but a thick mane of dark black hair falls from the throat, a patch of similar hair grows on the forehead, and the back and shoulders are greyish brown. There is no mane on the back of the neck, as is the case with the koodoo.

The Addax is a sand-loving animal, as is shown by the wide and spreading hoofs, which afford it a firm footing on the yielding soil. In all probability, this is one of the animals which would be taken, like the wild bull, in a net, being surrounded and driven into the toils by a number of hunters. It is not, however, one of the gregarious species, and is not found in those vast herds in which some of the antelopes love to assemble.

THE FALLOW-DEER, OR BUBALE

The word Jachmur evidently represents a species of antelope—Resemblance of the animal to the ox tribe—Its ox-like horns and mode of attack—Its capability of domestication—Former and present range of the Bubale—Its representation on the monuments of ancient Egypt—Delicacy of its flesh—Size and general appearance of the animal.

It has already been mentioned that in the Old Testament there occur the names of three or four animals, which clearly belong to one or other of three or four antelopes. Only one of these names now remains to be identified. This is the Jachmur, or Yachmur, a word which has been rendered in the Septuagint as Boubalos, and has been translated in our Authorized Version as Fallow Deer.

We shall presently see that the Fallow Deer is to be identified with another animal, and that the word Jachmur must find another interpretation. If we follow the Septuagint, and call it the Bubale, we shall identify it with a well-known antelope called by the Arabs the "Bekk'r-el-Wash," and known to zoologists as the Bubale (Acronotus bubalis).

This fine antelope would scarcely be recognised as such by an unskilled observer, as in its general appearance it much more resembles the ox tribe than the antelope. Indeed, the Arabic title, "Bekk'r-el-Wash," or Wild Cow, shows how close must be the resemblance to the oxen. The Arabs, and indeed all the Orientals in whose countries it lives, believe it not to be an antelope, but one of the oxen, and class it accordingly.

How much the appearance of the Bubale justifies them in this opinion may be judged by reference to the figure on page 143. The horns are thick, short, and heavy, and are first inclined forwards, and then rather suddenly bent backwards. This formation of the horns causes the Bubale to use his weapons after the manner of the bull, thereby increasing the resemblance between them. When it attacks, the Bubale lowers its head to the ground, and as soon as its antagonist is within reach, tosses its head violently upwards, or swings it with a sidelong upward blow. In either case, the sharp curved horns, impelled by the powerful neck of the animal, and assisted by the weight of the large head, become most formidable weapons.

It is said that in some places, where the Bubales have learned to endure the presence of man, they will mix with his herds for the sake of feeding with them, and by degrees become so accustomed to the companionship of their domesticated friends, that they live with the herd as if they had belonged to it all their lives. This fact shows that the animal possesses a gentle disposition, and it is said to be as easily tamed as the gazelle itself.

Even at the present day the Bubale has a very wide range, and formerly had in all probability a much wider. It is indigenous to Barbary, and has continued to spread itself over the greater part of Northern Africa, including the borders of the Sahara, the edges of the cultivated districts, and up the Nile for no small distance. In former days it was evidently a tolerably common animal of chase in Upper Egypt as there are representations of it on the monuments, drawn with the quaint truthfulness which distinguishes the monumental sculpture of that period.

THE BUBALE, OR FALLOW-DEER OF SCRIPTURE.

It is probable that in and about Palestine it was equally common, so that there is good reason why it should be specially named as one of the animals that were lawful food. Not only was its flesh permitted to be eaten, but it was evidently considered as a great dainty, inasmuch as the Jachmur is mentioned in 1 Kings iv. 23 as one of the animals which were brought to the royal table. "Harts and Roebucks and Fallow-Deer" are the wild animals mentioned in the passage alluded to.

THE SHEEP

Importance of Sheep in the Bible—The Sheep the chief wealth of the pastoral tribes—Arab shepherds of the present day—Wanderings of the flocks in search of food—Value of the wells—How the Sheep are watered—The shepherd usually a part owner of the flocks—Structure of the sheepfolds—The rock caverns of Palestine—David's adventure with Saul—Use of the dogs—The broad-tailed Sheep, and its peculiarities.

We now come to a subject which will necessarily occupy us for some little time.

There is, perhaps, no animal which occupies a larger space in the Scriptures than the Sheep. Whether in religious, civil, or domestic life, we find that the Sheep is bound up with the Jewish nation in a way that would seem almost incomprehensible, did we not recall the light which the New Testament throws upon the Old, and the many allusions to the coming Messiah under the figure of the Lamb that taketh away the sins of the world.

In treating of the Sheep, it will be perhaps advisable to begin the account by taking the animal simply as one of those creatures which have been domesticated from time immemorial, dwelling slightly on those points on which the sheep-owners of the old days differed from those of our own time.

The only claim to the land seems, in the old times of the Scriptures, to have lain in cultivation, or perhaps in the land immediately surrounding a well. But any one appears to have taken a piece of ground and cultivated it, or to have dug a well wherever he chose, and thereby to have acquired a sort of right to the soil. The same custom prevails at the present day among the cattle-breeding races of Southern Africa. The banks of rivers, on account of their superior fertility, were considered as the property of the chiefs who lived along their course, but the inland soil was free to all.

Had it not been for this freedom of the land, it would have been impossible for the great men to have nourished the enormous flocks and herds of which their wealth consisted; but, on account of the lack of ownership of the soil, a flock could be moved to one district after another as fast as it exhausted the herbage, the shepherds thus unconsciously imitating the habits of the gregarious animals, which are always on the move from one spot to another.

Pasturage being thus free to all, Sheep had a higher comparative value than is the case with ourselves, who have to pay in some way for their keep. There is a proverb in the Talmud which may be curtly translated, "Land sell, sheep buy."

The value of a good pasture-ground for the flocks is so great, that its possession is well worth a battle, the shepherds being saved from a most weary and harassing life, and being moreover fewer in number than is needed when the pasturage is scanty Sir S. Baker, in his work on Abyssinia, makes some very interesting remarks upon the Arab herdsmen, who are placed in conditions very similar to those of the Israelitish shepherds.

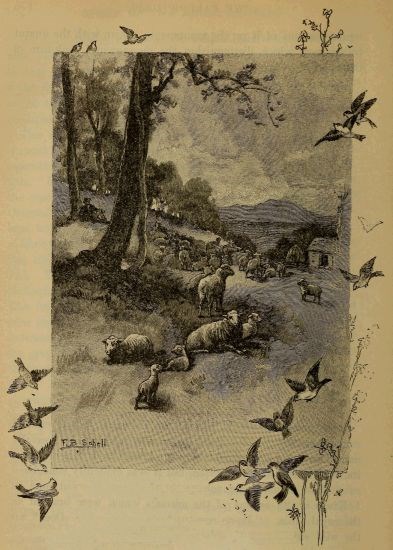

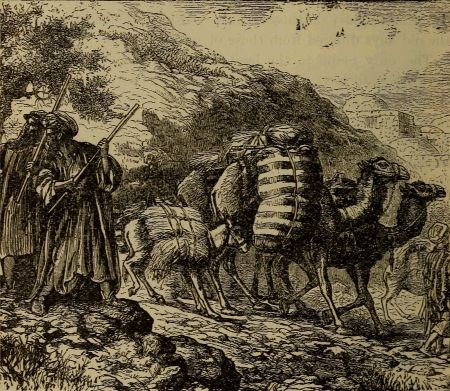

ARABS JOURNEYING TO FRESH PASTURES.

"The Arabs are creatures of necessity; their nomadic life is compulsory, as the existence of their flocks and herds depends upon the pasturage. Thus, with the change of seasons they must change their localities according to the presence of fodder for their cattle.... The Arab cannot halt in one spot longer than the pasturage will support his flocks. The object of his life being fodder, he must wander in search of the ever-changing supply. His wants must be few, as the constant change of encampment necessitates the transport of all his household goods; thus he reduces to a minimum his domestic furniture and utensils....

"This striking similarity to the descriptions of the Old Testament is exceedingly interesting to a traveller when residing among these curious and original people. With the Bible in one's hand, and these unchanged tribes before the eyes, there is a thrilling illustration of the sacred record; the past becomes the present, the veil of three thousand years is raised, and the living picture is a witness to the exactness of the historical description. At the same time there is a light thrown upon many obscure passages in the Old Testament by the experience of the present customs and figures of speech of the Arabs, which are precisely those that were practised at the periods described....

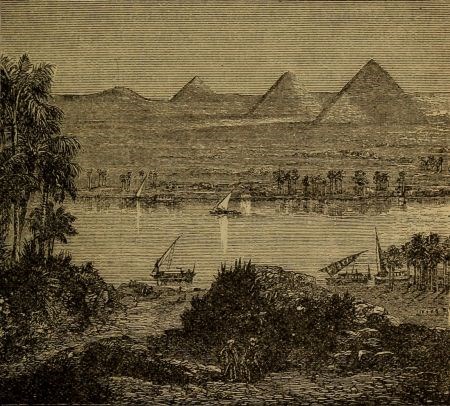

VIEW OF THE PYRAMIDS.

"Should the present history of the country be written by an Arab scribe, the style of the description would be precisely that of the Old Testament. There is a fascination in the unchangeable features of the Nile regions. There are the vast pyramids that have defied time, the river upon which Moses was cradled in infancy, the same sandy desert through which he led his people, and the watering-places where their flocks were led to drink. The wild and wandering Arabs, who thousands of years ago dug out the wells in the wilderness, are represented by their descendants, unchanged, who now draw water from the deep wells of their forefathers, with the skins that have never altered their fashion.