полная версия

полная версияStory of the Bible Animals

Take even one of our own toil-worn animals, turned out in a common to graze, and see the ingenuity which it displays when persecuted by the idle boys who generally frequent such places, and who try to ride every beast that is within their reach. It seems to divine at once the object of the boy as he steals up to it, and he takes a pleasure in baffling him just as he fancies that he has succeeded in his attempt.

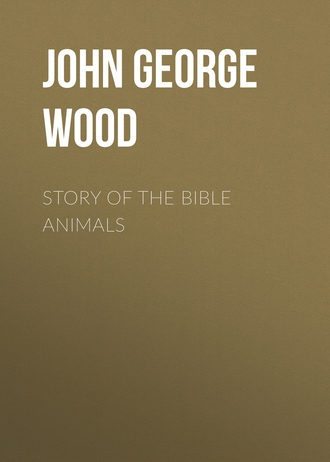

SYRIAN ASSES.

Should the Ass be kindly treated, there is not an animal that proves more docile, or even affectionate. Stripes and kicks it resents, and sets itself distinctly against them; and, being nothing but a slave, it follows the slavish principle of doing no work that it can possibly avoid.

Now, in the East the Ass takes so much higher rank than our own animal, that its whole demeanour and gait are different from those displayed by the generality of its brethren. "Why, the very slave of slaves," writes Mr. Lowth, in his "Wanderer in Arabia," "the crushed and grief-stricken, is so no more in Egypt: the battered drudge has become the willing servant. Is that active little fellow, who, with race-horse coat and full flanks, moves under his rider with the light step and the action of a pony—is he the same animal as that starved and head-bowed object of the North, subject for all pity and cruelty, and clothed with rags and insult?

"Look at him now. On he goes, rapid and free, with his small head well up, and as gay as a crimson saddle and a bridle of light chains and red leather can make him. It was a gladdening sight to see the unfortunate as a new animal in Egypt."

Hardy animal as is the Ass, it is not well adapted for tolerance of cold, and seems to degenerate in size, strength, speed, and spirit in proportion as the climate becomes colder. Whether it might equal the horse in its endurance of cold provided that it were as carefully treated, is perhaps a doubtful point; but it is a well-known fact that the horse does not necessarily degenerate by moving towards a colder climate, though the Ass has always been found to do so.

There is, of course, a variety in the treatment which the Ass receives even in the East. Signor Pierotti, whose work on the customs and traditions of Palestine has already been mentioned, writes in very glowing terms of the animal. He states that he formed a very high opinion of the Ass while he was in Egypt, not only from its spirited aspect and its speed, but because it was employed even by the Viceroy and the great Court officers, who may be said to use Asses of more or less intelligence for every occasion. He even goes so far as to say that, if all the Asses were taken away from Egypt, travel would be impossible.

The same traveller gives an admirable summary of the character of the Ass, as it exists in Egypt and Palestine. "What, then, are the characteristics of the ass? Much the same as those which adorn it in other parts of the East—namely, it is useful for riding and for carrying burdens; it is sensible of kindness, and shows gratitude; it is very steady, and is larger, stronger, and more tractable than its European congener; its pace is easy and pleasant; and it will shrink from no labour, if only its poor daily feed of straw and barley is fairly given.

"If well and liberally supplied, it is capable of any enterprise, and wears an altered and dignified mien, apparently forgetful of its extraction, except when undeservedly beaten by its masters, who, however, are not so much to be blamed, because, having learned to live among sticks, thongs, and rods, they follow the same system of education with their miserable dependants.

"The wealthy feed him well, deck him with fine harness and silver trappings, and cover him, when his work is done, with rich Persian carpets. The poor do the best they can for him, steal for his benefit, give him a corner at their fireside, and in cold weather sleep with him for more warmth. In Palestine, all the rich men, whether monarchs or chiefs of villages, possess a number of asses, keeping them with their flocks, like the patriarchs of old. No one can travel in that country, and observe how the ass is employed for all purposes, without being struck with the exactness with which the Arabs retain the Hebrew customs."

The result of this treatment is, that the Eastern Ass is an enduring and tolerably swift animal, vying with the camel itself in its powers of long-continued travel, its usual pace being a sort of easy canter. On rough ground, or up an ascent, it is said even to gain on the horse, probably because its little sharp hoofs give it a firm footing where the larger hoof of the horse is liable to slip.

The familiar term "saddling the Ass" requires some little explanation.

The saddle is not in the least like the article which we know by that name, but is very large and complicated in structure. Over the animal's back is first spread a cloth, made of thick woollen stuff, and folded several times. The saddle itself is a very thick pad of straw, covered with carpet, and flat at the top, instead of being rounded as is the case with our saddles. The pommel is very high, and when the rider is seated on it, he is perched high above the back of the animal. Over the saddle is thrown a cloth or carpet, always of bright colours, and varying in costliness of material and ornament according to the wealth of the possessor. It is mostly edged with a fringe and tassels.

The bridle is decorated, like that of the horse, with bells, embroidery, tassels, shells, and other ornaments.

As we may see from 2 Kings iv. 24, the Ass was generally guided by a driver who ran behind it, just as is done with donkeys hired to children here. Owing to the unchanging character of the East, there is no doubt that the "riders on asses" of the Scriptures rode exactly after the mode which is adopted at the present day. What that mode is, we may learn from Mr. Bayard Taylor's amusing and vivid description of a ride through the streets of Cairo:—

A STREET IN CAIRO, EGYPT.

"To see Cairo thoroughly, one must first accustom himself to the ways of these long-eared cabs, without the use of which I would advise no one to trust himself in the bazaars. Donkey-riding is universal, and no one thinks of going beyond the Frank quarters on foot. If he does, he must submit to be followed by not less than six donkeys with their drivers. A friend of mine who was attended by such a cavalcade for two hours, was obliged to yield at last, and made no second attempt. When we first appeared in the gateway of an hotel, equipped for an excursion, the rush of men and animals was so great that we were forced to retreat until our servant and the porter whipped us a path through the yelling and braying mob. After one or two trials I found an intelligent Arab boy named Kish, who for five piastres a day furnished strong and ambitious donkeys, which he kept ready at the door from morning till night. The other drivers respected Kish's privilege, and henceforth I had no trouble.

"The donkeys are so small that my feet nearly touched the ground, but there is no end to their strength and endurance. Their gait, whether in pace or in gallop, is so easy and light that fatigue is impossible. The drivers take great pride in having high-cushioned red saddles, and in hanging bits of jingling brass to the bridles. They keep their donkeys close shorn, and frequently beautify them by painting them various colours. The first animal I rode had legs barred like a zebra's, and my friend's rejoiced in purple flanks and a yellow belly. The drivers ran behind them with a short stick, punching them from time to time, or giving them a sharp pinch on the rump. Very few of them own their donkeys, and I understood their pertinacity when I learned that they frequently received a beating on returning home empty-handed.

"The passage of the bazaars seems at first quite as hazardous on donkey-back as on foot; but it is the difference between knocking somebody down and being knocked down yourself, and one certainly prefers the former alternative. There is no use in attempting to guide the donkey, for he won't be guided. The driver shouts behind, and you are dashed at full speed into a confusion of other donkeys, camels, horses, carts, water-carriers, and footmen. In vain you cry out 'Bess' (enough), 'Piacco,' and other desperate adjurations; the driver's only reply is: 'Let the bridle hang loose!' You dodge your head under a camel-load of planks; your leg brushes the wheel of a dust-cart; you strike a fat Turk plump in the back; you miraculously escape upsetting a fruit-stand; you scatter a company of spectral, white-masked women; and at last reach some more quiet street, with the sensations of a man who has stormed a battery.

BEGGAR IN THE STREETS OF CAIRO.

"At first this sort of riding made me very nervous, but presently I let the donkey go his own way, and took a curious interest in seeing how near a chance I ran of striking or being struck. Sometimes there seemed no hope of avoiding a violent collision; but, by a series of the most remarkable dodges, he generally carried you through in safety. The cries of the driver running behind gave me no little amusement. 'The hawadji comes! Take care on the right hand! Take care on the left hand! O man, take care! O maiden, take care! O boy, get out of the way! The hawadji comes!' Kish had strong lungs, and his donkey would let nothing pass him; and so wherever we went we contributed our full share to the universal noise and confusion."

NIGHT-WATCH IN CAIRO.

This description explains several allusions which are made in the Scriptures to treading down the enemies in the streets, and to the chariots raging and jostling against each other in the ways.

The Ass was used in the olden time for carrying burdens, as it is at present, and, in all probability, carried them in the same way. Sacks and bundles are tied firmly to the pack-saddle; but poles, planks, and objects of similar shape are tied in a sloping direction on the side of the saddle, the longer ends trailing on the ground, and the shorter projecting at either side of the animal's head. The North American Indians carry the poles of their huts, or wigwams, in precisely the same way, tying them on either side of their horses, and making them into rude sledges, upon which are fastened the skins that form the walls of their huts. The same system of carriage is also found among the Esquimaux, and the hunters of the extreme North, who harness their dogs in precisely the same manner. The Ass, thus laden, becomes a very unpleasant passenger through the narrow and crowded streets of an Oriental city; and many an unwary traveller has found reason to remember the description of Issachar as the strong Ass between two burdens.

The Ass was also used for agriculture, and was employed in the plough, as we find from many passages. See for example, "Blessed are ye that sow beside all waters, that send forth thither the feet of the ox and the ass" (Isa. xxxii. 20). Sowing beside the waters is a custom that still prevails in all hot countries, the margins of rivers being tilled, while outside this cultivated belt there is nothing but desert ground.

The ox and the Ass were used in the first place for irrigation, turning the machines by which water was lifted from the river, and poured into the trenches which conveyed it to all parts of the tilled land. If, as is nearly certain, the rude machinery of the East is at the present day identical with those which were used in the old Scriptural times, they were yoked to the machine in rather an ingenious manner. The machine consists of an upright pivot, and to it is attached the horizontal pole to which the ox or Ass is harnessed. A machine exactly similar in principle may be seen in almost any brick-field in England; but the ingenious part of the Eastern water-machine is the mode in which the animal is made to believe that it is being driven by its keeper, whereas the man in question might be at a distance, or fast asleep.

The animal is first blindfolded, and then yoked to the end of the horizontal bar. Fixed to the pivot, and rather in front of the bar, is one end of a slight and elastic strip of wood. The projecting end, being drawn forward and tied to the bridle of the animal, keeps up a continual pull, and makes the blinded animal believe that it is being drawn forward by the hand of a driver. Some ingenious but lazy attendants have even invented a sort of self-acting whip, i.e. a stick which is lifted and allowed to fall on the animal's back by the action of the wheel once every round.

The field being properly supplied with water, the Ass is used for ploughing it. It is worthy of mention that at the present day the prohibition against yoking an ox and an Ass together is often disregarded. The practice, however, is not a judicious one, as the slow and heavy ox does not act well with the lighter and more active animal, and, moreover, is apt to butt at its companion with its horns in order to stimulate it to do more than its fair proportion of the work.

There is a custom now in Palestine which probably existed in the days of the Scriptures, though I have not been able to find any reference to it. Whenever an Ass is disobedient and strays from its master, the man who captures the trespasser on his grounds clips a piece out of its ear before he returns it to its owner. Each time that the animal is caught on forbidden grounds it receives a fresh clip of the ear. By looking at the ears of an Ass, therefore, any one can tell whether it has ever been a straggler; and if so, he knows the number of times that it has strayed, by merely counting the clip-marks, which always begin at the tip of the ear, and extend along the edges. Any Ass, no matter how handsome it may be, that has many of those clips, is always rejected by experienced travellers, as it is sure to be a dull as well as a disobedient beast.

There are recorded in the Scriptures two remarkable circumstances connected with the Ass, which, however, need but a few words. The first is the journey of Balaam from Pethor to Moab, in the course of which there occurred that singular incident of the Ass speaking in human language (see Numb. xxii. 21, 35). The second is the well-known episode in the story of Samson, where he is recorded as breaking the cords with which his enemies had bound him, and killing a thousand Philistines with the fresh jaw-bone of an Ass.

THE WILD ASS

Various allusions to the Wild Ass—Its swiftness and wildness—The Wild Ass of Asia and Africa—How the Wild Ass is hunted—Excellence of its flesh—Meeting a Wild Ass—Origin of the domestic Ass—The Wild Asses of Quito.

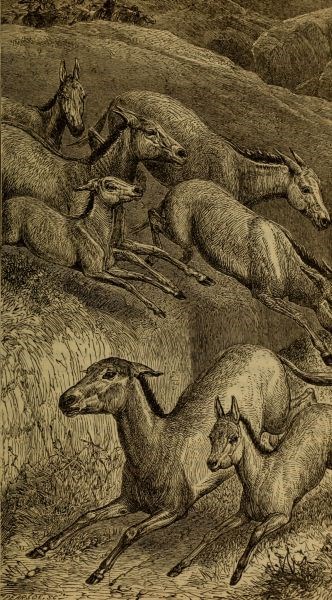

There are several passages of Scripture in which the Wild Ass is distinguished from the domesticated animal, and in all of them there is some reference made to its swiftness, its intractable nature, and love of freedom. It is an astonishingly swift animal, so that on the level ground even the best horse has scarcely a chance of overtaking it. It is exceedingly wary, its sight, hearing, and sense of scent being equally keen, so that to approach it by craft is a most difficult task.

Like many other wild animals, it has a custom of ascending hills or rising grounds, and thence surveying the country, and even in the plains it will generally contrive to discover some earth-mound or heap of sand from which it may act as sentinel and give the alarm in case of danger. It is a gregarious animal, always assembling in herds, varying from two or three to several hundred in number, and has a habit of partial migration in search of green food, traversing large tracts of country in its passage.

It has a curiously intractable disposition, and, even when captured very young, can scarcely ever be brought to bear a burden or draw a vehicle.

Attempts have been often made to domesticate the young that have been born in captivity, but with very slight success, the wild nature of the animal constantly breaking out, even when it appears to have become moderately tractable.

Although the Wild Ass does not seem to have lived within the limits of the Holy Land, it was common enough in the surrounding country, and, from the frequent references made to it in Scriptures, was well known to the ancient Jews.

We will now look at the various passages in which the Wild Ass is mentioned, and begin with the splendid description in Job xxxix. 5-8:

"Who hath sent out the wild ass free? or who hath loosed the bands of the wild ass?

"Whose house I have made the wilderness, and the barren lands (or salt places) his dwellings.

"He scorneth the multitude of the city, neither regardeth he the crying of the driver.

"The range of the mountains is his pasture, and he searcheth after every green thing."

Here we have the animal described with the minuteness and truth of detail that can only be found in personal knowledge; its love of freedom, its avoidance of mankind, and its migration in search of pasture.

Another allusion to the pasture-seeking habits of the animal is to be found in chapter vi. of the same book, verse 5: "Doth the wild ass bray when he hath grass?" or, according to the version of the Jewish Bible, "over tender grass?"

A very vivid account of the appearance of the animal in its wild state is given by Sir R. Kerr Porter, who was allowed by a Wild Ass to approach within a moderate distance, the animal evidently seeing that he was not one of the people to whom it was accustomed, and being curious enough to allow the stranger to approach him.

"The sun was just rising over the summit of the eastern mountains, when my greyhound started off in pursuit of an animal which, my Persians said, from the glimpse they had of it, was an antelope. I instantly put spurs to my horse, and with my attendants gave chase. After an unrelaxed gallop of three miles, we came up with the dog, who was then within a short stretch of the creature he pursued; and to my surprise, and at first vexation, I saw it to be an ass.

"Upon reflection, however, judging from its fleetness that it must be a wild one, a creature little known in Europe, but which the Persians prize above all other animals as an object of chase, I determined to approach as near to it as the very swift Arab I was on could carry me. But the single instant of checking my horse to consider had given our game such a head of us that, notwithstanding our speed, we could not recover our ground on him.

"I, however, happened to be considerably before my companions, when, at a certain distance, the animal in its turn made a pause, and allowed me to approach within pistol-shot of him. He then darted off again with the quickness of thought, capering, kicking, and sporting in his flight, as if he were not blown in the least, and the chase was his pastime. When my followers of the country came up, they regretted that I had not shot the creature when he was within my aim, telling me that his flesh is one of the greatest delicacies in Persia.

"The prodigious swiftness and the peculiar manner in which he fled across the plain coincided exactly with the description that Xenophon gives of the same animal in Arabia. But above all, it reminded me of the striking portrait drawn by the author of the Book of Job. I was informed by the Mehnander, who had been in the desert when making a pilgrimage to the shrine of Ali, that the wild ass of Irak Arabi differs in nothing from the one I had just seen. He had observed them often for a short time in the possession of the Arabs, who told him the creature was perfectly untameable.

"A few days after this discussion, we saw another of these animals, and, pursuing it determinately, had the good fortune to kill it."

It has been suggested by many zoologists that the Wild Ass is the progenitor of the domesticated species. The origin of the domesticated animal, however, is so very ancient, that we have no data whereon even a theory can be built. It is true that the Wild and the Domesticated Ass are exactly similar in appearance, and that an Asinus hemippus, or Wild Ass, looks so like an Asiatic Asinus vulgaris, or Domesticated Ass, that by the eye alone the two are hardly distinguishable from each other. But with their appearance the resemblance ends, the domestic animal being quiet, docile, and fond of man, while the wild animal is savage, intractable, and has an invincible repugnance to human beings.

HUNTING WILD ASSES.

This diversity of spirit in similar forms is very curious, and is strongly exemplified by the semi-wild Asses of Quito. They are the descendants of the animals that were imported by the Spaniards, and live in herds, just as do the horses. They combine the habits of the Wild Ass with the disposition of the tame animal. They are as swift of foot as the Wild Ass of Syria or Africa, and have the same habit of frequenting lofty situations, leaping about among rocks and ravines, which seem only fitted for the wild goat, and into which no horse can follow them.

Nominally, they are private property, but practically they may be taken by any one who chooses to capture them. The lasso is employed for the purpose, and when the animals are caught they bite, and kick, and plunge, and behave exactly like their wild relations of the Old World, giving their captors infinite trouble in avoiding the teeth and hoofs which they wield so skilfully. But, as soon as a load has once been bound on the back of one of these furious creatures, the wild spirit dies out of it, the head droops, the gait becomes steady, and the animal behaves as if it had led a domesticated life all its days.

THE MULE

Ancient use of the Mule—Various breeds of Mule—Supposed date of its introduction into Palestine—Mule-breeding forbidden to the Jews—The Mule as a saddle-animal—Its use on occasions of state—The king's Mule—Obstinacy of the Mule.

There are several references to the Mule in the Holy Scriptures, but it is remarkable that the animal is not mentioned at all until the time of David, and that in the New Testament the name does not occur at all.

The origin of the Mule is unknown, but that the mixed breed between the horse and the ass has been employed in many countries from very ancient times is a familiar fact. It is a very strange circumstance that the offspring of these two animals should be, for some purposes, far superior to either of the parents, a well-bred Mule having the lightness, surefootedness, and hardy endurance of the ass, together with the increased size and muscular development of the horse. Thus it is peculiarly adapted either for the saddle or for the conveyance of burdens over a rough or desert country.

The Mules that are most generally serviceable are bred from the male ass and the mare, those which have the horse as the father and the ass as the mother being small, and comparatively valueless. At the present day, Mules are largely employed in Spain and the Spanish dependencies, and there are some breeds which are of very great size and singular beauty, those of Andalusia being especially celebrated. In the Andes, the Mule has actually superseded the llama as a beast of burden.

Its appearance in the sacred narrative is quite sudden. In Gen. xxxvi. 24, there is a passage which seems as if it referred to the Mule: "This was that Anah that found the mules in the wilderness." Now the word which is here rendered as Mules is "Yemim," a word which is not found elsewhere in the Hebrew Scriptures. The best Hebraists are agreed that, whatever interpretation may be put upon the word, it cannot possibly have the signification that is here assigned to it. Some translate the word as "hot springs," while the editors of the Jewish Bible prefer to leave it untranslated, thus signifying that they are not satisfied with any rendering.

MULES OF THE EAST.