полная версия

полная версияStory of the Bible Animals

During the war of conquest which Joshua led, the chariot plays a somewhat important part. As long as the war was carried on in the rugged mountainous parts of the land, no mention of the chariot is made; but when the battles had to be fought on level ground, the enemy brought the dreaded chariots to bear upon the Israelites. In spite of these adjuncts, Joshua won the battles, and, unlike David, destroyed the whole of the Horses and burned the chariots.

Many years afterwards, a still more dreadful weapon, the iron chariot, was used against the Israelites by Jabin. This new instrument of war seems to have cowed the people completely; for we find that by means of his nine hundred chariots of iron Jabin "mightily oppressed the children of Israel" for twenty years. It has been well suggested that the possession of the war chariot gave rise to the saying of Benhadad's councillors, that the gods of Israel were gods of the hills, and so their army had been defeated; but that if the battle were fought in the plain, where the chariots and Horses could act, they would be victorious.

So dreaded were these weapons, even by those who were familiar with them and were accustomed to use them, that when the Syrians had besieged Samaria, and had nearly reduced it by starvation, the fancied sound of a host of chariots and Horses that they heard in the night caused them all to flee and evacuate the camp, leaving their booty and all their property in the hands of the Israelites.

Whether the Jews ever employed the terrible scythe chariots is not quite certain, though it is probable that they may have done so; and this conjecture is strengthened by the fact that they were employed against the Jews by Antiochus, who had "footmen an hundred and ten thousand, and horsemen five thousand and three hundred, and elephants two and twenty, and three hundred chariots armed with hooks" (2 Macc. xiii. 2). Some commentators think that by the iron chariots mentioned above were signified ordinary chariots armed with iron scythes projecting from the sides.

ELIJAH IS CARRIED UP.

By degrees the chariot came to be one of the recognised forces in war, and we find it mentioned throughout the books of the Scriptures, not only in its literal sense, but as a metaphor which every one could understand. In the Psalms, for example, are several allusions to the war-chariot." He maketh wars to cease unto the end of the earth; He breaketh the bow, and cutteth the spear in sunder; He burneth the chariot in the fire" (Ps. xlvi. 9). Again: "At Thy rebuke, O God of Jacob, both the chariot and horse are cast into a dead sleep" (Ps. lxxvi. 6). And: "Some trust in chariots, and some in horses: but we will remember the name of the Lord our God" (Ps. xx. 7). Now, the force of these passages cannot be properly appreciated unless we realize to ourselves the dread in which the war-chariot was held by the foot-soldiers. Even cavalry were much feared; but the chariots were objects of almost superstitious fear, and the rushing sound of their wheels, the noise of the Horses' hoofs, and the shaking of the ground as the "prancing horses and jumping chariots" (Nah. iii. 2) thundered along, are repeatedly mentioned.

See, for example, Ezek. xxvi. 10: "By reason of the abundance of his horses their dust shall cover thee: thy walls shall shake at the noise of the horsemen, and of the wheels, and of the chariots." Also, Jer. xlvii. 3: "At the noise of the stamping of the hoofs of his strong horses, at the rushing of his chariots, and at the rumbling of his wheels, the fathers shall not look back to their children for feebleness of hands." See also Joel ii. 4, 5: "The appearance of them is as the appearance of horses; and as horsemen, so shall they run.

"Like the noise of chariots on the tops of mountains shall they leap, like the noise of a flame of fire that devoureth the stubble, as a strong people set in battle array."

In several passages the chariot and Horse are used in bold imagery as expressions of Divine power: "The chariots of God are twenty thousand, even thousands of angels: the Lord is among them, as in Sinai, in the holy place" (Ps. lxviii. 17). A similar image is employed in Ps. civ. 3: "Who maketh the clouds His chariot: who walketh upon the wings of the wind." In connexion with these passages, we cannot but call to mind that wonderful day when the unseen power of the Almighty was made manifest to the servant of Elisha, whose eyes were suddenly opened, and he saw that the mountain was full of Horses and chariots of fire round about Elisha.

The chariot and horses of fire by which Elijah was taken from earth are also familiar to us, and in connexion with the passage which describes that wonderful event, we may mention one which occurs in the splendid prayer of Habakkuk (iii. 8): "Was the Lord displeased against the rivers? was Thine anger against the rivers? was Thy wrath against the sea, that Thou didst ride upon Thine horses and Thy chariots of salvation?"

By degrees the chariot came to be used for peaceful purposes, and was employed as our carriages of the present day, in carrying persons of wealth. That this was the case in Egypt from very early times is evident from Gen. xli. 43, in which we are told that after Pharaoh had taken Joseph out of prison and raised him to be next in rank to himself, the king caused him to ride in the second chariot which he had, and so to be proclaimed ruler over Egypt. Many years afterwards we find him travelling in his chariot to the land of Goshen, whither he went to meet Jacob and to conduct him to the presence of Pharaoh.

At first the chariot seems to have been too valuable to the Israelites to have been used for any purpose except war, and it is not until a comparatively late time that we find it employed as a carriage, and even then it is only used by the noble and wealthy. Absalom had such chariots, but it is evident that he used them for purposes of state, and as appendages of his regal rank. Chariots or carriages were, however, afterwards employed by the Israelites as freely as by the Egyptians, from whom they were originally procured; and accordingly we find Rehoboam mounting his chariot and fleeing to Jerusalem, Ahab riding in his chariot from Samaria to Jezreel, with Elijah running before him; and in the New Testament we read of the chariot in which sat the chief eunuch of Ethiopia whom Philip baptized (Acts viii. 28).

As to the precise form and character of these chariots, they are made familiar to us by the sculptures and paintings of Egypt and Assyria, from both of which countries the Jews procured the vehicles. Differing very slightly in shape, the principle of the chariot was the same; and it strikes us with some surprise that the Assyrians, the Egyptians, and the Jews, the three wealthiest and most powerful nations of the world, should not have invented a better carriage. They lavished the costliest materials and the most artistic skill in decorating the chariots, but had no idea of making them comfortable for the occupants.

They were nothing but semicircular boxes on wheels, and of very small size. They were hung very low, so that the occupants could step in and out without trouble, though they do not seem to have had the sloping floor of the Greek or Roman chariot. They had no springs, but, in order to render the jolting of the carriage less disagreeable, the floor was made of a sort of network of leathern ropes, very tightly stretched so as to be elastic. The wheels were always two in number, and generally had six spokes.

To the side of the chariot was attached the case which contained the bow and quiver of arrows, and in the case of a rich man these bow-cases were covered with gold and silver, and adorned with figures of lions and other animals. Should the chariot be intended for two persons, two bow-cases were fastened to it, the one crossing the other. The spear had also its tubular case, in which it was kept upright, like the whip of a modern carriage.

Two Horses were generally used with each chariot, though three were sometimes employed. They were harnessed very simply, having no traces, and being attached to the central pole by a breast-band, a very slight saddle, and a loose girth. On their heads were generally fixed ornaments, such as tufts of feathers, and similar decorations, and tassels hung to the harness served to drive away the flies. Round the neck of each Horse passed a strap, to the end of which was attached a bell. This ornament is mentioned in Zech. xiv. 20: "In that day shall there be upon the bells of the horses, Holiness unto the Lord"—i.e. the greeting of peace shall be on the bells of the animals once used in war.

Sometimes the owner drove his own chariot, even when going into battle, but the usual plan was to have a driver, who managed the Horses while the owner or occupant could fight with both his hands at liberty. In case he drove his own Horse, the reins passed round his waist, and the whip was fastened to the wrist by a thong, so that when the charioteer used the bow, his principal weapon, he could do so without danger of losing his whip.

Thus much for the use of the chariot in war; we have now the Horse as the animal ridden by the cavalry.

As was the case with the chariot, the war-horse was not employed by the Jews until a comparatively late period of their history. They had been familiarized with cavalry during their long sojourn in Egypt, and in the course of their war of conquest had often suffered defeat from the horsemen of the enemy. But we do not find any mention of a mounted force as forming part of the Jewish army until the days of David, although after that time the successive kings possessed large forces of cavalry.

Many references to mounted soldiers are made by the prophets, sometimes allegorically, sometimes metaphorically. See, for example, Jer. vi. 23: "They shall lay hold on bow and spear; they are cruel, and have no mercy; their voice roareth like the sea; and they ride upon horses, set in array as men for war against thee, O daughter of Zion." The same prophet has a similar passage in chap. l. 42, couched in almost precisely the same words. And in chap. xlvi. 4, there is a further reference to the cavalry, which is specially valuable as mentioning the weapons used by them. The first call of the prophet is to the infantry: "Order ye the buckler and shield, and draw near to battle" (verse 3); and then follows the command to the cavalry, "Harness the horses; and get up, ye horsemen, and stand forth with your helmets; furbish the spears, and put on the brigandines." The chief arms of the Jewish soldier were therefore the cuirass, the helmet, and the lance, the weapons which in all ages, and in all countries, have been found to be peculiarly suitable to the horse-soldier.

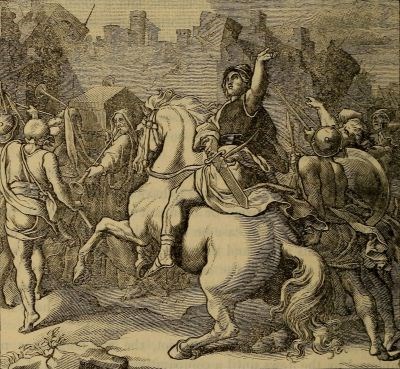

THE ISRAELITES, LED BY JOSHUA, TAKE JERICHO.

Being desirous of affording the reader a pictorial representation of the war and state chariots, I have selected Egypt as the typical country of the former, and Assyria of the latter. Both have been executed with the greatest care in details, every one of which, even to the harness of the Horses, the mode of holding the reins, the form of the whip, and the offensive and defensive armour, has been copied from the ancient records of Egypt and Nineveh.

We will first take the war-chariot of Egypt.

ANCIENT BATTLE-FIELD.

This form has been selected as the type of the war-chariot because the earliest account of such a force mentions the war-chariots of Egypt, and because, after the Israelites had adopted chariots as an acknowledged part of their army, the vehicles, as well as the trained Horses, and probably their occupants, were procured from Egypt.

The scene represents a battle between the imperial forces and a revolted province, so that the reader may have the opportunity of seeing the various kinds of weapons and armour which were in use in Egypt at the time of Joseph. In the foreground is the chariot of the general, driven at headlong speed, the Horses at full gallop, and the springless chariot leaping off the ground as the Horses bound along. The royal rank of the general in question is shown by the feather fan which denotes his high birth, and which is fixed in a socket at the back of his chariot, much as a coachman fixes his whip. The rank of the rider is further shown by the feather plumes on the heads of his Horses.

By the side of the chariot are seen the quiver and bow-case, the former being covered with decorations, and having the figure of a recumbent lion along its sides. The simple but effective harness of the Horses is especially worthy of notice, as showing how the ancients knew, better than the moderns, that to cover a Horse with a complicated apparatus of straps and metal only deteriorates from the powers of the animal, and that a Horse is more likely to behave well if he can see freely on all sides, than if all lateral vision be cut off by the use of blinkers.

Just behind the general is the chariot of another officer, one of whose Horses has been struck, and is lying struggling on the ground. The general is hastily giving his orders as he dashes past the fallen animal. On the ground are lying the bodies of some slain enemies, and the Horses are snorting and shaking their heads, significative of their unwillingness to trample on a human being. By the side of the dead man are his shield, bow, and quiver, and it is worthy of notice that the form of these weapons, as depicted upon the ancient Egyptian monuments, is identical with that which is still found among several half-savage tribes of Africa.

In the background is seen the fight raging round the standards. One chief has been killed, and while the infantry are pressing round the body of the rebel leader and his banner on one side, on the other the imperial chariots are thundering along to support the attack, and are driving their enemies before them. In the distance are seen the clouds of dust whirled into the air by the hoofs and wheels, and circling in clouds by the eddies caused by the fierce rush of the vehicles, thus illustrating the passage in Jer. iv. 13: "Behold, he shall come up as clouds, and his chariots shall be as a whirlwind: his horses are swifter than eagles. Woe unto us! for we are spoiled." The reader will see, by reference to the illustration, how wonderfully true and forcible is this statement, the writer evidently having been an eye-witness of the scene which he so powerfully depicts.

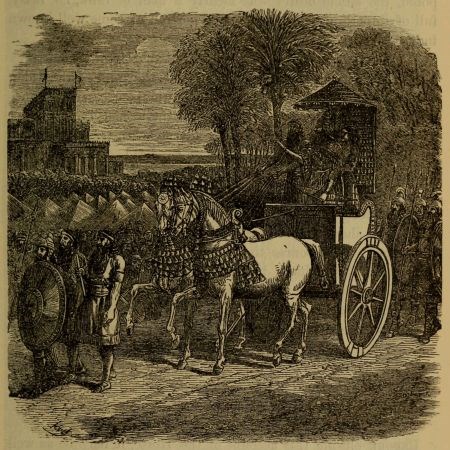

CHARIOT OF STATE.

The second scene is intentionally chosen as affording a strong contrast to the former. Here, instead of the furious rush, the galloping Horses, the chariots leaping off the ground, the archers bending their bows, and all imbued with the fierce ardour of battle, we have a scene of quiet grandeur, the Assyrian king making a solemn progress in his chariot after a victory, accompanied by his attendants, and surrounded by his troops, in all the placid splendour of Eastern state.

Chief object in the illustration stands the great king in his chariot, wearing the regal crown, or mitre, and sheltered from the sun by the umbrella, which in ancient Nineveh, as in more modern times, was the emblem of royalty. By his side is his charioteer, evidently a man of high rank, holding the reins in a business-like manner; and in front marches the shield-bearer. In one of the sculptures from which this illustration was composed, the shield-bearer was clearly a man of rank, fat, fussy, full of importance, and evidently a portrait of some well-known individual.

The Horses are harnessed with remarkable lightness, but they bear the gorgeous trappings which befit the rank of the rider, their heads being decorated with the curious successive plumes with which the Assyrian princes distinguished their chariot Horses, and the breast-straps being adorned with tassels, repeated in successive rows like the plumes of the head.

The reader will probably notice the peculiar high action of the Horses. This accomplishment seems to have been even more valued among the ancients than by ourselves, and some of the sculptures show the Horses with their knees almost touching their noses. Of course the artist exaggerrated the effect that he wanted to produce; but the very fact of the exaggeration shows the value that was set on a high and showy action in a Horse that was attached to a chariot of state. The old Assyrian sculptors knew the Horse well, and delineated it in a most spirited and graphic style, though they treated it rather conventionally. The variety of attitude is really wonderful, considering that all the figures are profile views, as indeed seemed to have been a law of the historical sculptures.

Before closing this account of the Horse, it may be as well to remark the singular absence of detail in the Scriptural accounts. Of the other domesticated animals many such details are given, but of the Horse we hear but little, except in connexion with war. There are few exceptions to this rule, and even the oft-quoted passage in Job, which goes deeper into the character of the Horse than any other portion of the Scriptures, only considers the Horse as an auxiliary in battle. We miss the personal interest in the animal which distinguishes the many references to the ox, the sheep, and the goat; and it is remarkable that even in the Book of Proverbs, which is so rich in references to various animals, very little is said of the Horse.

ANCIENT EGYPTIAN SCULPTURE REPRESENTING A VICTORIOUS KING IN HIS CHARIOT SLAYING HIS ENEMIES.

MUMMY OF AN EGYPTIAN KING (OVER THREE THOUSAND YEARS OLD).

THE ASS

Importance of the Ass in the East—Its general use for the saddle—Riding the Ass not a mark of humility—The triumphal entry—White Asses—Character of the Scriptural Ass—Saddling the Ass—Samson and Balaam.

In the Scriptures we read of two breeds of Ass, namely, the Domesticated and the Wild Ass. As the former is the more important of the two, we will give it precedence.

In the East, the Ass has always played a much more important part than among us Westerns, and on that account we find it so frequently mentioned in the Bible. In the first place, it is the universal saddle-animal of the East. Among us the Ass has ceased to be regularly used for the purposes of the saddle, and is only casually employed by holiday-makers and the like. Some persons certainly ride it habitually, but they almost invariably belong to the lower orders, and are content to ride without a saddle, balancing themselves in some extraordinary manner just over the animal's tail. In the East, however, it is ridden by persons of the highest rank, and is decorated with saddle and harness as rich as those of the horse.

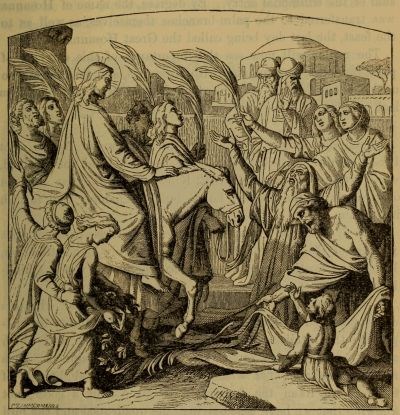

So far from the use of the Ass as a saddle-animal being a mark of humility, it ought to be viewed in precisely the opposite light. In consequence of the very natural habit of reading, according to Western ideas, the Scriptures, which are books essentially Oriental in all their allusions and tone of thought, many persons have entirely perverted the sense of one very familiar passage, the prophecy of Zechariah concerning the future Messiah. "Rejoice greatly, O daughter of Zion; shout, O daughter of Jerusalem: behold, thy King cometh unto thee: He is just, and having salvation; lowly, and riding upon an ass, and upon a colt the foal of an ass" (Zech. ix. 9).

Now this passage, as well as the one which describes its fulfilment so many years afterwards, has often been seized upon as a proof of the meekness and lowliness of our Saviour, in riding upon so humble an animal when He made His entry into Jerusalem. The fact is, that there was no humility in the case, neither was the act so understood by the people. He rode upon an Ass as any prince or ruler would have done who was engaged on a peaceful journey, the horse being reserved for war purposes. He rode on the Ass, and not on the horse, because He was the Prince of Peace and not of war, as indeed is shown very clearly in the context. For, after writing the words which have just been quoted, Zechariah proceeds as follows (ver. 10): "And I will cut off the chariot from Ephraim, and the horse from Jerusalem, and the battle bow shall be cut off: and He shall speak peace unto the heathen: and His dominion shall be from sea even to sea, and from the river even to the ends of the earth."

Meek and lowly was He, as became the new character, hitherto unknown to the warlike and restless Jews, a Prince, not of war, as had been all other celebrated kings, but of peace. Had He come as the Jews expected—despite so many prophecies—their Messiah to come, as a great king and conqueror, He might have ridden the war-horse, and been surrounded with countless legions of armed men. But He came as the herald of peace, and not of war; and, though meek and lowly, yet a Prince, riding as became a prince, on an Ass colt which had borne no inferior burden.

That the act was not considered as one of lowliness is evident from the manner in which it was received by the people, accepting Him as the Son of David, coming in the name of the Highest, and greeting Him with the cry of "Hosanna!" ("Save us now,") quoted from verses 25, 26 of Ps. cxviii.: "Save now, I beseech Thee, O Lord: O Lord, I beseech Thee, send now prosperity."

"Blessed be He that cometh in the name of the Lord."

ENTERING JERUSALEM.

The palm-branches which they strewed upon the road were not chosen by the attendant crowd merely as a means of doing honour to Him whom they acknowledged as the Son of David. They were necessarily connected with the cry of "Hosanna!" At the Feast of Tabernacles, it was customary for the people to assemble with branches of palms and willows in their hands, and for one of the priests to recite the Great Hallel, i.e. Ps. cxiii. and cxviii. At certain intervals, the people responded with the cry of "Hosanna!" waving at the same time their palm-branches. For the whole of the seven days through which the feast lasted they repeated their Hosannas, always accompanying the shout with the waving of palm-branches, and setting them towards the altar as they went in procession round it.

Every child who could hold a palm-branch was expected to take part in the solemnity, just as did the children on the occasion of the triumphal entry. By degrees, the name of Hosanna was transferred to the palm-branches themselves, as well as to the feast, the last day being called the Great Hosanna.

The reader will now see the importance of this carrying of palm-branches, accompanied with Hosannas, and that those who used them in honour of Him whom they followed into Jerusalem had no idea that He was acting any lowly part.

Again, the woman of Shunem, who rode on an Ass to meet Elisha, a mission in which the life of her only child was involved, was a woman of great wealth (2 Kings iv. 8), who was able not only to receive the prophet, but to build a chamber, and furnish it for him.

Not to multiply examples, we see from these passages that the Ass of the East was held in comparatively high estimation, being used for the purposes of the saddle, just as would a high-bred horse among ourselves.

Consequently, the Ass is really a different animal. In this country he is repressed, and seldom has an opportunity for displaying the intellectual powers which he possesses, and which are of a much higher order than is generally imagined. It is rather remarkable, that when we wish to speak slightingly of intellect we liken the individual to an Ass or a goose, not knowing that we have selected just the quadruped and the bird which are least worthy of such a distinction.

Putting aside the bird, as being at present out of place, we shall find that the Ass is one of the cleverest of our domesticated animals. We are apt to speak of the horse with a sort of reverence, and of the Ass with contemptuous pity, not knowing that, of the two animals, the Ass is by far the superior in point of intellect. It has been well remarked by a keen observer of nature, that if four or five horses are in a field, together with one Ass, and there be an assailable point in the fence, the Ass is sure to be the animal that discovers it, and leads the way through it.